Family Sabbatical & (Careful) Hope for Community-Building | Rewilding Update

Feun Foo Permaculture & Rewilding Update (March 2025) --- [Estimated reading time: 20 min.]

Please note that this Update does not contain any new knowledge or meaningful insights, but merely serves to explain my long inactivity – to bridge the gap, so to speak. A lot of the following might be considered “preaching to the choir,” and I suspect that in terms of community-building many of you are much further than I am, but it is only now that its true relevance finally starts to become obvious to us.

Moreover, I am aware that it’s not March anymore, but you’ll see why it took me a while to finally finish this piece. As always, there’s plenty to do!

More Updates (hopefully) coming soon!

A much-needed family sabbatical

It has been a while since my last Update, and since I haven’t had the opportunity to do so, let this be the occasion to wish you, dear reader, a not-too-terrible new year – wishing the collapse-aware audience of this blog a “happy new year” might easily come across as cynical these days, especially with all that’s been happening recently.

While I usually try to stick to topics that are at least remotely related to the “Rewilding” part of the name of this series, the following might seem like a digression into purely personal matters. But since the term “rewilding” relates as much to reforestation, habitat restoration and permaculture as it does to re-discovering our true human Nature and syncing ourselves to a life more in tune with it, the matter of family & community is actually much more relevant to the rewilding process than one might initially assume. For better or worse, humans are highly social animals, and – no matter if deep in the Pleistocene or in the scorched-Earth, post-materialist, consumer-capitalist Anthropocene – without our band, group or community we’re pretty much screwed.

This is a lesson Karn and I are learning right now.

It’s one of the things you’re vaguely aware of, but that easily gets drowned out by the constant chatter of our electronic devices or pushed into the background for more immediate concerns such as paying rent, or – as in our case – tending the land to feed ourselves. Regrettably, most industrialized societies have only sparse remnants of real community (especially in overdeveloped nations),1 and hence many people today have never actually experienced the profoundly empowering, invigorating and soothing feeling of being part of one.

Here in Southeast Asia, community is, for the most part, still alive and vibrant – at least in the countryside. People spend hours every day socializing, and it is still very common here to talk to your neighbors, to drop by some friends on the other side of the village, and be invited (or invite others) to supper, all on a daily basis. Tiny mom-and-pops stores selling basic necessities are some of the pulsing centers of connectivity, as people don’t only get groceries, but use the opportunity to meet others and have a good, old-fashioned, face-to-face chat.

They could go to town once per week and get a multipack of the same item at the new supermarket, simultaneously saving themselves time & money: the repeated walks to the store and the wholesale price plus five Baht discount. Given the rather precarious financial situation of the people, the latter would certainly make sense from an economic perspective.

But the potential for social interaction outweighs any marginal monetary benefit, and humans are not “economic creatures” – at least not in the commonly understood sense of the term.

Moreover, many families in rural Thailand are living close together in small subclusters of houses, or all under the same roof in larger farmhouses. It is still normal for farmers to live in multi-generational households, and even if a young couple builds their own house, it is not uncommon that they live right next to their parents (or another family member).

Everything gets easier if you have a few pairs of extra hands close by. Whether farm work, child-rearing, cooking meals or other household chores, tasks can be evenly distributed among those that happen to have time at any given point. And if someone goes to the market or to visit the doctor, or has to attend a meeting or a celebration, others can quickly jump in to ensure nothing is left undone.

This system might seem rather chaotic to Western eyes, and there is very little of what we call “privacy,” but it still functions surprisingly good.2

If the biggest downside of the life we’re leading is not being around our family, the second biggest is that we are not part of a larger, physical community. We did not plan for this, but – as is so often the case – life unfolded around us without us being able to influence anything but the broadest direction (and, subsequently, a few of the details). I did not plan to emigrate to a different country at the tender age of twenty-one. We did not plan on moving to a secluded hillside in a province where we don’t know anyone. As usually shit just happens, and we try our best to navigate it.

But it is becoming clear that we will need to shift – or, better, to expand – our focus beyond our own little homestead, and towards the village in the valley below.

The increasingly alluring fantasy of “homesteading” (a couple, or a small nuclear family living off the land), as a response to the metacrisis or to just “get away from it all,” is enabled by and utterly dependent on an artificial global system of epic proportions – one that includes six-continent supply chains, a planet-wide network of infrastructure, and a massively inflated population of a certain hairless ape (and the handful of species it feeds on). Without this unfathomably large and complex techno-industrial behemoth homesteading simply wouldn’t be possible, at least not with the level of comfort and convenience we’ve become accustomed to. In terms of standard of living it would be a lot closer to medieval peasantry than to “cottagecore” – and even medieval peasants had to rely on one another.

Since homesteading is still reliant on the techno-industrial system (and has been ever since its inception during the “Wild West” period of the currently concluding Yankee saga, despite being advertised as “peak independence”), it is not, as such, a viable alternative to it. Furthermore, it stems from the same kind of thinking that is partly responsible for the mess we find ourselves in. Additionally, homesteading creates business opportunities. It constitutes a market that can be catered to, and, as a result, it is (and was) part and parcel of the economy. A typical homestead could never produce all the materials and tools it needs to sustain itself, so homesteaders need to buy a broad range of industrial products (such as certain machines & replacement parts, clothes, pots, mason jars, fencing, nails, lumber, etc.).

No, to make this “living-off-the-land” lifestyle work in the low-tech future we’re entering now, characterized by increasing scarcity and steadily deteriorating institutions and infrastructure, we will need to depend on others – on real people, in our community. Not like-minded online acquaintances, and not strangers whom we pay money or machines that gobble up non-renewable resources.

Capitalism has brainwashed us into believing that Independence and Freedom™ are byproducts of the accumulation of wealth, since now you can simply use money to buy things instead of having to depend on any particular person. Make no mistake: you still depend on people, though not on anyone in particular. This works well as long as the system is up and running, money has a commonly agreed upon value, and there are willing strangers desperate enough to toil for wages, even if they’d much rather not. But the most important question is: where do you get all that money from in the first place?

And, by extension, can you really call yourself free if you have to be at a designated place at a designated time for the majority of your days, where you have very little agency over what you do and how?

Money can certainly buy you certain amounts of certain freedoms, but they are more than nullified by the freedoms you have to give up in order to obtain that money. And once money becomes worthless, the only viable replacement is community.

One thing I always tell volunteers, potential dropouts & aspiring rewilders is that the Cult of the Individual is one of the most harmful myths perpetuated by the dominant culture.3 You can’t do this with only two people, let alone all by yourself. We can’t do this, at least not in the long term. Foraging and subsistence farming only work well if you’re part of a larger community, even if we’re only talking about half a dozen people. Or if you have a large family. There is a reason why the multi-generation household has been the norm for the entirety of our species’ existence – until very, very recently.

Since we can’t know how much longer we can take the conveniences of the globalized economy for granted, it is about time for us to reach out to those closest to us, if not in terms of familiarity or ideological overlap, then at least in terms of locality.

This correlates neatly with our progress with the land we inhabit. Now that we’ve (roughly) finished setting up the garden and are finally feeling like our roots are growing strong enough to anchor us firmly in place, the next challenge dawns. We already feel like a bunch of damn grown-ups managing our household and adjacent permaculture farm/rewilding project, but to truly grow more mature, there is yet another aspect that needs to be considered.

The dominant culture makes it seem like life is all about the transition from a state of dependence (childhood) to one of in-dependence (adulthood), yet independence is only one necessary step towards the next step of growth (and its ultimate goal), inter-dependence.4

Abraham Maslow, who famously formulated the Hierarchy of Needs, first thought that self-actualization is the highest need – an idea strongly influenced by the dominant culture’s pathological fixation on individualism.5 Shortly before his death, he added yet another rung on top of this conceptualization: self-transcendence.

“Transcendence refers to the very highest and most inclusive or holistic levels of human consciousness, behaving and relating, as ends rather than means, to oneself, to significant others, to human beings in general, to other species, to nature, and to the cosmos.” [Emphasis mine]

– Abraham Maslow

For the first few years, we were simply too busy to pay much heed to other humans. We had to construct Maslow’s Pyramid of Needs from the ground up, but not soon after we finished the foundation, I started feeling an incessant longing for connection to others that started to grow stronger and stronger, culminating in a motivational nadir during the last rainy season in which things seemed pretty hopeless, despite our (considerable) real-world achievements up to that point.6

While I am certainly able to be an introvert temporarily, I only truly flourish in social settings and am able to tap into near inexhaustible sources of energy when I’m around other people whose company I enjoy. As much as I hate using tech metaphors, it felt a lot like my social batteries were drained, and they finally got a desperately needed recharge right before drying up completely.

The tide finally started turning when my family came to visit over the Christmas holidays, a much-anticipated event for everyone involved. We had talked about it for many years, and it’s far from easy to coordinate such a thing with five adults who have completely different schedules, but recent events on the world stage made it look like sooner is probably better than later.

My parents have never traveled outside of Europe, so this trip was an entirely novel experience for them. Especially my mom was quite worried, about the long flight, malicious insects and snakes lurking in the underbrush, unfamiliar food, and the (supposed) heat and humidity.7 To complicate things, my youngest brother is autistic (Asperger’s), which presented a whole host of other challenges – yet all of our worries, it turned out, were entirely unfounded. Everyone enjoyed every single meal we prepared, and adjusted without any issues to the different environmental conditions. Together we visited some of our favorite places in the area, took a stroll through the surrounding orchards, hiked through the jungle, swam in waterfalls, and we even went to the beach once.

My family got to see the side of Thailand that few tourists get to experience: its “true face,” so to speak, not the sanitized and beautified version popularized by travel ads.

We knew that we’d be quite busy for the entire two weeks my family was here, so we tried to prepare by doing whatever we could in advance and making sure there’s as little hard work to do as possible during their stay with us. In anticipation of this holiday we felled a few stems of giant bamboo, emptied the “thundermug” of our compost toilet, fixed the chicken fence (again!), and finished as many vegetable beds as possible.

The time around New Year is usually the period in which we re-dig our vegetable beds, whose soil has become compacted after rainy season. But since last year’s rainy season ceased early, we had a few weeks’ time to plant the first round of vegetable seedlings, and timed the seeding of the vegetable seeds Karn brought home from her visit to the hilltribes so that they’d have to be planted after the family visit.

Thankfully, in cold season there’s always a few things to do that make for excellent group activities, so while we exchanged news, stories and gossip we also harvested and dehulled coffee cherries, made cinnamon, and peeled dry loofahs. Each day we gathered firewood and cooked all our meals together,8 fed the chickens, and prepared a large bouquet of edible foliage for our rabbits.

For two truly exhilarating days, the Thai side of our family joined us as well, heroically enduring two 10-hour road trips to meet the German side and exchange gifts, feast together and finally start to get to know each other. Karn’s parents are farmers, so we had to find someone willing to watch their cattle for two nights. By the morning of the third day Karn’s father grew worried about his animals and was eager to return home – just like we worry about our animal companions whenever we’re somewhere else, and how my grandfather did about his flock of sheep.

Since for Thai standards it is very, very uncommon for someone to be physically separated from their family to the extent that I am (the last time we visited my family in Germany was in 2018), people here often suspect that I come from an estranged or otherwise dysfunctional family – yet nothing could be further from the truth. My in-laws now see me with different eyes as well, not a semi-orphaned castaway abandoned by those closest to him, but as a still somewhat quaint dude that nonetheless has a loving & caring family, despite the vast geographical distance separating us.

The more I think about it, the more obvious it is that my family is the greatest privilege I have – and this of course includes the Thai side.

All we had to do for the entire two-week sabbatical was the most basic maintenance work, which every family member was more than happy to help with, and as a result it even felt like a real holiday for us. It was definitely the most beautiful and memorable Christmas ever – for all of us!

Usually, we’re pretty much busy at all times, and even though we might work less than conventional farmers (we don’t work overtime to feed city people), what has been true for farmers throughout the ages is also valid for us: there’s no day off, and no holidays. As I’ve said repeatedly in past Updates: feeding yourself (and running a low-tech household!) is a full-time activity. When you practice conventional monocrop agriculture and make use of various machines and chemical inputs you can easily produce enough calories to feed yourself and society at large, but without mechanical helpers, a sizeable plot of land and a large family we need the same amount of time merely to feed ourselves (and a small number of people around us with whom we occasionally share our surplus).

When you live like us, you’re bound to the land. For the past six and a half years, I’ve slept every single night in our garden.9 The chickens, rabbits & cats need to be fed, watered, cuddled & looked after, and the trajectory of the agro-ecosystem we’ve become a part of needs to be nudged, ever so slightly, into the direction we have in mind. When the vegetables and young trees are thirsty we have to bring them water, and when we run low on any of the crucial resources this lifestyle requires (firewood, charcoal powder, potting soil, mulch, compost, rocks, sand, animal manure, coconut fiber, ashes, etc.) we have to replenish our stockpile as fast as possible or we run into real problems. Dirty laundry piles up if we don’t wash it (by hand, mind you), and the dishes don’t do themselves.

And when we’re hungry, eating out is not an option – we have to harvest, prepare and cook our own food, from scratch, each and every time. All those tasks alone would be enough to keep us busy, but additionally there’s books to read, friends to correspond with, and essays to write.

Although we were still surprisingly productive during our sabbatical, there were plenty of tasks that we didn’t get around finishing – and we’ve just now, quite recently, caught up with the accruing chores. (Incidentally, this is also the reason why I haven’t posted any Updates to this blog in a while – the garden always comes first.)

This served as a reminder that any serious attempt at subsistence farming mixed with the rising cost of living in general, a social fabric that’s bursting at the seams, and a rapidly escalating global climate crisis is, to put it bluntly, a shit ton of work. Gone are the days where you would have ample free time to follow various hobbies; less than once per week do we have time to play Wingspan (a gift from my brother) or any other board- or card game, and only slightly more often than that does Karn find time to practice the guitar.

If we would have someone to regularly share the daily chores with, the percentage of free time would increase substantially, since the difference between cooking for two people and cooking for three or four people is not that much in terms of time invested, but it means that two or three people are free to do other things, and chores can be rotated and/or shared to get stuff done more quickly.

At least the “Magic Five-Year Threshold” finally fully kicks in, albeit with a bit of delay. The vegetable beds are truly splendid this year, teeming with beauty and vigor, flaunting boastful hues of green and showering us with an abundance of cherry tomatoes, leafy greens, and – surprise, surprise – even a few pumpkins!

But more on that in the next Update.

My parents (and especially my younger brother, who stayed with me for a year when I was still a volunteer in Krabi province, and already visited us for a month right after we moved here) actually expected to help out a bit more, and when my mom joked that she’d love to live with us when she retires but is afraid she won’t be able to contribute much, I told her that there would be plenty of tasks for old people, tasks that (to be honest) aren’t among my personal favorites: peeling pigeon pea pods, cleaning, drying, and labeling various seeds to store them, sieving & mixing ingredients for potting soil or various soil amendments, weaving baskets and other utensils (and preparing the materials needed therefore, which takes up the bulk of the time), processing fruit harvests, preparing food, etc.

No matter from which perspective we view the issue, things would be easier if it wasn’t just us two.

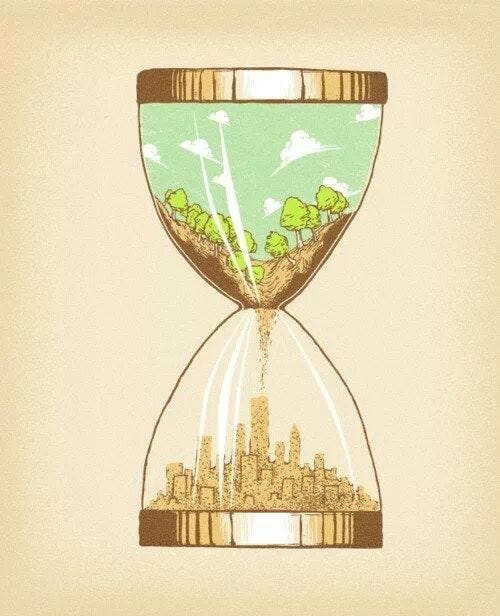

As I’ve detailed throughout past Rewilding Updates and other essays on this blog, last year has been quite challenging for us, in many ways. Although it should not come as a surprise – especially not for me – realizing just how far beyond “Peak Civilization” we already are (and how steep the downwards curve in front of us looks like) stunned me. Somehow I thought we’d still have a bit more time, but now I’m certain we don’t. We most certainly won’t have enough time to do most of the things we wanted to do. No fancy hipster-esque eco-resort bungalows, no floating pavilion for fishing in the pond, perhaps not even the bamboo birdwatching tower we had wanted to build for so long now.

Initially, we made it our mission to not only invent a new subsistence mode adapted to our unique local conditions from scratch, but also an entire culture surrounding it. I’ve come to believe that those were the idealistic, hopelessly naïve pipe dreams of a bunch of overly optimistic, starry-eyed hippies. You need more than two people to call yourself a culture, and even partly replacing an established one takes immense amounts of time and dedication.

Established beliefs are deep-rooted and can only be supplanted gradually, although it is possible that the accelerating breakdown of the global system might help this process along and even speed it up a bit. Uprooting beliefs is no painless endeavor, and by necessity you turn up quite some soil as well. But broken ground is the best substrate for new seeds to grow, and pioneers establish themselves quickly once conditions are ideal.

It seems like the best we can hope for is to carefully nudge the existing social arrangement into a general direction that more closely resembles the vision we have for the world, all the while making compromise after compromise. Perhaps, if we’re lucky, things become easier as more and more people realize that the Old Order is inevitably coming to an end. As the saying goes, Rome wasn’t built in a day – and its collapse took a bit longer than that as well.

A new hope (?)

When we moved here, we thought that if we just do our thing long enough, at least some people would take notice and follow along. Yet for the first six years, only a single farmer and his family took a short tour through our garden, and only a handful of other villagers briefly dropped by.10 Yes, we are a bit isolated, and our garden is too far away from the village for people to just casually swing by, but still, I couldn’t shake a feeling of disappointment and disillusionment.

And while there might be a slight uptick in interest as things continue to deteriorate, I fear that it will be too little, too late. It takes time for the soil to recover and for the trees to grow, and making the transition from chemical-intensive conventional farming to organic subsistence farming is only possible if you can a) still rely on (super)markets to feed you during the transition, b) you’re not too deep in debt, and c) have either savings to draw from or a secondary source of income.

Oh, and d) if you’re part of a community (duh!), but everyone else around us knows that already.

Given the general state of the world, our lives are definitely not that bad, and compared to almost everyone else we have very little reason to complain. The only important thing we’re still missing is community, and this proves to be the hardest task to date.

A common piece of advice you hear from a lot of people in collapse-aware circles – it seems every other guest on The Great Simplification concludes with the same words – is that we have to “build community.” But in a society as divided and polarized as the contemporary, globalized, influencer-influenced hodgepodge currently swirling down the drain of history, in which people can’t even agree on the fundamentals of reality, such as task seems truly Herculean.

And while the general worldview of the people around us leaves much to be desired (to say the least – more on that in an upcoming Update), at least the village community is still relatively intact, although profit-oriented thinking, greed and status have done immense damage already.

We still haven’t given up hope that, sooner or later, one or more family members (from either side) will come and join us.11 As everyone here in rural Thailand knows, in terms of community building family is the ultimate ace up the sleeve. If you have a large enough family around you, well, there you go.

Another one of our perpetual biggest hopes for the past years were new neighbors,12 perhaps disillusioned city people looking for a change in scenery and a quieter life, anyone who sees the world just a little bit more like we do – a community of interrelated and interdependent living organisms – and less like an endless pool of resources to be exploited and converted into money.

And there are little glimmers of hope, although they might appear insufficient given the sheer scale of the predicament we’re facing. One of our neighbors recently told us that she’s “tired of spraying pesticides,” and that she “wants to stop” – already the second time we hear this sort of sentiment from someone in this village!

A tiny step for mankind, but a giant leap for a commercial durian farmer.

Over the past few months, her family has already started planting vegetables and raising ducks, albeit still (partly) for commercial purposes and still not as ecologically sound as we would advise, and she has told us of her plans to slowly move away from durian monoculture13 and towards something more diverse and thus resilient.14

Even better (and even more surprising), for about a year already there’s a young Laotian couple living together with her, paid on a day-to-day basis as farmhands, whom we just recently had the opportunity to meet. We’ve seen them around occasionally, but never thought much of it, and until a few weeks ago we never had the chance to sit down and talk to them. They are, to our great surprise, open-minded, hard-working, and as down-to-earth as preciously few from their generation. Moreover, they know about the benefits of organic cultivation and are not afraid to criticize both pesticide-dependent industrial farming and Chinese neo-colonialism, both of which currently ravage their homeland – the reason why they’re here in the first place.

As if the Universe is finally answering (some of) our prayers, our neighbor has allowed them to start planting a vegetable garden right next to the lower border of our land, among the young longan trees in that part of her orchard. She has pledged to stop spraying pesticides in this area (!!) – a huge win for our cause! – and they might even move their duck pen there. Thanks in part to her two young daughters, she seriously considers raising a few rabbits as well, which we of course support enthusiastically.

It almost seems like the tiny area of increasing biodiversity (of which our garden is the epicenter) is finally starting to expand, slowly, both into the neighbors’ orchard and into the bamboo thicket of the adjacent Nature Reserve.15

The prospect of gradually becoming part of a wider community feels incredibly good, and after years of bleak outlooks and anxiety about our future it comes just at the right time.

But I try to curb my enthusiasm and stay realistic; only time will tell if the young couple from Laos will become our Tak and Bay.16

But time is slowly running out, and if some sort of paradigm shift were to happen, it should happen right fucking now – as I’ve been saying for the past ten years. The window is closing fast, and if we’re gonna make it, it’s gonna be a close shave, both for us and (hopefully) for the community in which we’re embedded.

Previous Rewilding Updates:

I write stuff like the above in my free time, when I’m not tending the piece of land we’re rewilding here at Feun Foo. As a subsistence farmer by profession I don’t have a regular income, so if you have a few bucks to spare please consider supporting my work with a small donation:

If you want to support our project on a regular basis, you can become a Patron for as little as $1 per month - cheaper than a paid subscription!

Not too long ago people used to be part of all sorts of clubs, leagues and associations (still far from natural communities, but much better than nothing), but they’ve slowly been replaced by (semi-)solitary immersion in digital technology.

With a few important exceptions, of course. These days, money and status are among the main concerns of the common people, and so there is a lot of competing and comparing going on, especially between families.

The Myth of Progress being another one.

Read more about this shift from Dependence to Independence to Interdependence in Chusana Prasertkul’s latest piece.

All too often, it is still his unfinished theory that is being promoted (with self-actualization being the “highest goal”), even though it is instinctively obvious that people who have successfully “self-actualized” might still feel lonely, empty, or “as if something is missing.”

Karn initially felt a bit guilty, as if she wasn’t enough or didn’t do enough. Yet none of this is her fault: she is the only reason I even made it so far, and as her partner there is nothing more I could possibly wish for. But one person cannot fulfill all social needs of another, at least not in the long term. We humans are social creatures, and it takes more than two people to form a society.

It was much colder than they expected, with temperatures ranging around 15°C on the first few days.

Astonishingly, in the entire two weeks we only ate at a (rural) restaurant twice.

Karn has more immediate family obligations occasionally and helps with the annual rice harvest, but apart from that it’s the same for her.

Ever since the elephant visit last month, we had visitors – mostly our neighbors’ kids and their farm hands – several times per week!

If everything else fails, I often joke that we might just shelter some refugees as soon as cities start becoming uninhabitable. If we would have the funds, we might already consider employing two farmhands in an arrangement similar to that of our neighbors. But since our way of gardening doesn’t pay, and people are not desperate enough to work for only board and lodging, it seems we will have to be patient for a little longer.

Most of the neighbors we have are light years away from an ecological awakening, as I will explain in one of the next installments in this series.

As I’ve detailed elsewhere, durian farming faces a precarious future, and problems are already piling up sky-high.

Right now she’s considering avocadoes as a main cash crop. Not ideal, in our eyes, but a lot better than Monthong durian – easily the weakest and neediest fruit trees we’ve ever seen.

Every year, we cut back the running bamboo a few meters more, and each year the trees that sprout up and grow in its stead get taller and stronger. If you only remove the bamboo, diversity increases pretty much automatically.

A reference to the climate fiction I started writing, based (rather uncreatively) on the absolute best-case scenario I see for my wife and me in the place we currently inhabit. Since it is obvious that we can’t do all that alone, in the story there’s a like-minded younger couple living with us that forms the inner circle of the post-collapse culture of semi-nomadic jungle dwellers and shifting cultivators around which the story revolves.

Glad to hear things are going well for you guys :) It’s good to hear you are getting closer to your community. I think any chance of reaching or influencing people has to come from you all actively trying to integrate and participate with people, winning “hearts and minds” as it were. Both in terms of convincing others, and leading by example showing another way. Otherwise, people are just going to think of you guys as different, or maybe not even know about you!

The hope would be that as modernity and global capitalism degrades, there is a feedback loop of others who feel similarly and are tired of the old way or realize it can’t continue, and need another model of what to follow. In that situation, you’d be in a much better position if you’re already friends with half the valley and maybe even been gifting plants around the place or giving advice to lay the groundwork, vs hoping they’ll come to you.

A warm and uplifting post compared to your usual! I also sometimes get the feeling of being in a village when more people are here and everyone is busy with various tasks, contributing and helping. Other than the practicalities, it really is more fun. Occassionally someone calls for help and even if i am tired then, i find a boost of energy and purpose. Deep inside we all want to serve and be part of something bigger (nature, community, etc).

I get your point about social battery too. I have always thought myself as an introvert and happy to be by myself, but my entire life before this has been in urban places where often I wish there were less people. Now that I am here, I am more happy to see people.

My orang asli (indigenous person) friend who lives with many families around him always asks if I am bored here. I think reading and writing are other ways to socialize, kinda like listening or speaking to someone, but people that don't do it much (or kids) have a much stronger need to do it with real people.