Gardening in a Post-1.5°C World & Lessons from the Dust Bowl | Rewilding Update

Feun Foo Permaculture & Rewilding Update (August 2024) - Part One (Theory/Thoughts) --- [Estimated reading time: 30 min.]

What an utterly insane year – and we’re only halfway through it! A lot has happened, and it’s about time for a brief recap.

This Rewilding Update1 should have been finished well over a month ago, but if you’ve read this blog for a while, well… You know me. Somewhat naively, I initially planned to publish regular short(-ish) updates about what we do in our garden, mixed with some random thoughts & anecdotes, every four months. But since our life & environment seems to have no intention to allow me to follow a regular working schedule, it is exceedingly difficult to set apart a certain period every day in which to write.

Additionally, the longer I take to write this, the more stories there are to tell – and the longer this draft becomes. I’ve finally decided to publish the current (and long overdue) Rewilding Update as a two-part series, the first more focused more on theoretical things (Theory/Thoughts), and the second about what we actually did in the material world (Practice/Actions).

(Click here to read the previous Update – October 2023)

Goodbye La Niña, hello El Niño!

So far, it has definitely been a year of heightened anxiety. I have disquieting memories of the last El Niño in 2016 (when I was still living on a small permaculture farm in the southern province of Krabi). At the height of dry season our pond dried up, banana plants died in droves, and our vegetable beds withered under the tropical sun. We tried to make the best out of it, harvesting kilos of clams from the soft mud at the bottom of the pond, and after a series of fish deaths (probably due to asphyxiation), we decided to empty out the pond. So we got our fishing net, and after a bit of haphazard splashing and jumping around in the muddy broth, our fridge was filled to the brim with fish. We feasted for the next two weeks – a scrap of comfort amidst the desolation.

That fateful year in which climate change first turned reality for me was a life-altering turning point. To experience water scarcity (and the creeping sense of desperation that comes with it) first-hand – as a middle-class white kid from the suburbs – gave me a renewed sense of awe for the forces we’ve collectively helped unleash, and instilled a sense of urgency that still drives me today.

Last year, there were plenty of reasons to worry about the coming El Niño (record-breaking ocean temperatures, for starters), and yet – somewhat fatalistically – I welcomed him in with a bitter grin. After three consecutive years of relentless downpours, near-perpetually soggy soil, low yields, damp firewood and armies of land leeches caused by his sister, La Niña, I felt I was more than ready for a bit of sustained sunshine, some mosquito-free months, and unlimited barefoot time.

Hence, at the end of the last Rewilding Update (October 2023), I naively (and somewhat bitterly) stated that I hope for a strong El Niño, so that it might help to wake people up to the climate reality we’re facing – and compel them to finally take action.

The strong El Niño materialized, but – surprise, surprise! – there has been absolutely no meaningful change, neither among peoples’ attitudes nor in regards to farming methods. No, it seems that Daniel Quinn was right when he categorized the dominant culture’s standard approach to problems:

“If it didn’t work least year – instead of trying something else entirely – let us now try to do more of the same thing that already didn’t work last year!”

So, over the entire year, more trees were cut down to “eliminate competition” for the main fruit crops in the area, more pesticides were sprayed and more fertilizers applied to make up for last year’s lost profits, and more ponds were dug deeper with giant machinery, creating craters in the landscape that look like someone was trying to build portals to the underworld.2

Meanwhile, the ubiquitous agrochemical stores are making a killing (quite literally), since people steadfastly believe that increasing inputs will automatically rise outputs, one of many myths the chemical manufacturers are spreading to increase revenue.3 Additionally, as a friend from the village recently told us, many “pests” seem increasingly unaffected by insecticides. He sprayed his entire orchard, came back the next day, and the caterpillars he wanted to exterminate were still happily munching on young durian leaves. Yet the response has not been to abandon pesticides because they have clearly become ineffective, but – on the chemical store clerk’s advice – to increase the dose even further, and mix even more different insecticides together.

A common regional joke has it that people used to hope their daughter would marry a durian farmer, but now they hope she marries the owner of a pesticide & fertilizer shop.

As someone who deeply cares about the survival of as much of the biosphere as anyhow possible, the most pressing question now is:

What has to happen in order for people to actually change their behavior in fundamental ways?

History might hold the answer.

Lessons from “The Dust Bowl”

Over one of the previous weeks,4 we watched the 2012 documentary miniseries “The Dust Bowl” – which I can’t recommend enough – and the whole thing got us thinking. The parallels to our current situation are eerie.

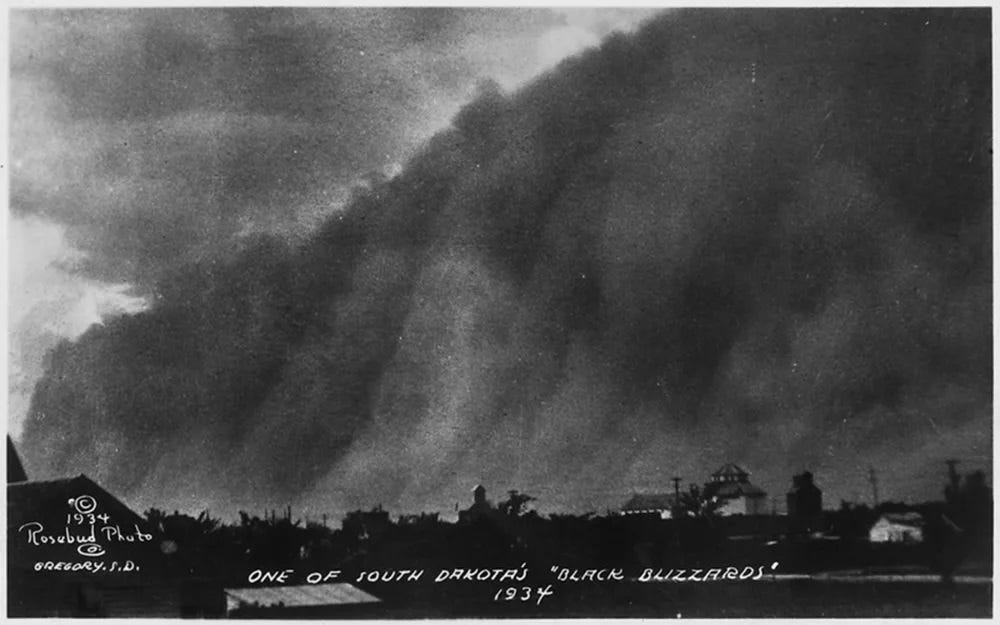

Here we have a historical precedent for a man-made environmental disaster (owing to human greed & myopia, combined with stark ecological and mild climatic changes) that, in a matter of years, escalated into a truly apocalyptic catastrophe of (quite literally) biblical proportions. Black storms, several miles high and hundreds of miles wide, descended onto the featureless landscape every other week, engulfing towns and villages and turning the once fertile prairies into a moonscape that resembled the Sahara desert more than anything else – with the crucial difference, as one commentator put it, that “in the Sahara there’s fewer fools trying to farm it.”

Within a short time yields dropped dramatically, health declined, countless people lost everything and became homeless, even shopkeepers and other small business owners eventually went bankrupt in droves, and many devout Christians were convinced that Judgement Day was imminent.5

Initially, most people remained optimistic, and reassured each other that the next year will surely be better than the last. Slowly, that confidence in a better future started eroding as the storms intensified and stripped the land bare.

History might not repeat itself, but it sure as hell rhymes.

Ultimately, the Dust Bowl was “solved” in the same way that the dominant culture “solved” so many of the problems that plague it incessantly: it was prolonged by technological innovation, essentially kicking the can down the road. After some promising initial changes towards less invasive agricultural practices (such as the use of different plows, cover crops and contour plowing) and ecological conservation (planting windbreaks, leaving farmland fallow and restoring grasslands), farmers started drawing up fossil water from the Ogallala aquifer – a non-renewable resource – which has sustained agriculture in the area ever since. Continuous large-scale agriculture in the Great Plains (and many other similar regions around the world) is a luxury we owe to cheap fossil energy powering ever-larger water pumps. But once enough wells dry up, the Dust Bowl will return in full force, further fueled by the dramatic shift in climate we’ve witnessed over the past few years.

People are generally extremely reluctant to critically self-examine their deeply held beliefs, and hate having their carefully constructed, much-cherished worldviews questioned. For most farmers to admit that the predominant method of food production is causing ecological mayhem on scales that threaten widespread collapse of everything they hold dear is too frightening a thought to entertain. They’d concomitantly have to admit to themselves that everything they’ve done for their entire working lives (and, in many cases, everything their parents did) was wrong. They’d have to admit that they’re guilty, or at the very least complicit.

When a documentary titled “The Plow that Broke the Plains,” detailing how short-sighted agricultural practices and human greed directly caused this unprecedented environmental catastrophe, was first screened in cinemas in 1936, farmers in the Dust Bowl were outraged. The film alleged that it was all their fault!

But outrage and anger are merely the immediate “knee-jerk” reactions to a perceived insult to our persona. Once they settle, a more rational examination can follow. I can imagine that after those farmers got home from the movie theater and were laying in bed that night, at least some of them had to concede to themselves that the underlying message was broadly correct. Things had to change.

They had to change.

The little glimmer of hope in all of this lays in the fact that people were ultimately able to admit their mistakes, and came up with a few adequate responses. But it took a decade of time, and the outright collapse of the ecosystem, the economy, and civilized society for them to arrive at this point.

Moreover, that glimmer is further eclipsed by the stark contrast to today’s reality. We can’t just hope for endless government aid and subsidies, because resources are already stretched thin. We can’t wait for better years either, because climate change is accelerating, pushing the Earth’s climatic regime further towards instability. And migrating to unaffected places doesn’t guarantee a better life, because climate chaos and economic collapse happen globally, and borders around the world are tightened as cross-border movement is increasingly restricted for everyone who’s not wealthy.

Just like one hundred years ago, there are quite a few people today who have actual ideas, solutions & responses, ways to mitigate damage and increase the resilience of agricultural systems, human societies and the ecological communities they’re embedded in. But those powerful enough to implement those changes have become so self-obsessed and alienated from the issues that really matter that we can’t trust them to listen to the right people and make the right choices.

Furthermore, while we can certainly expect some level of ecological recovery as soon as oil becomes expensive enough to slow down the plundering of the planet, we simply can’t expect the climate to return to previous stability after another decade or so, and we have no reason to believe that especially the cultivation of grains (on which this entire culture is built) is going to get any easier from now on. However the processes we’ve helped set in motion ultimately play out, it looks a lot like “amber waves of grain” are a thing of the past.

The hard lesson the Dust Bowl holds for us is that before people actually change their minds and ways the economy has to collapse, great parts of the population have to die truly horrific early deaths, whole communities must become uprooted, and the entire environment has to become a hostile moonscape. Only then will the most stubborn among us grudgingly admit that things can’t continue as they used to.

And so it seems all we can do is wait until society collectively hits “rock bottom,” and hope that it comes sooner rather than later – and that “rock bottom” in the 21st century is a tad higher than it was a century ago.6

Here in Thailand, it increasingly seems that we are pretty close already.

“Drought season” & “flood season”

It was hot this dry season, much hotter than during past years – the most severe dry season in living memory for farmers in many parts of Thailand. Hot enough for immature Durian fruit to crack open while still on the tree, for ponds to dry up, and for entire orchards to wither and die. Desperate for rain, the Department of Royal Rainmaking and Agricultural Aviation (yes, that’s a thing here!) flew their entire fleet of planes nonstop for well over a month, spreading powdered salt over the entire landscape in a doomed effort to seed clouds in the absence of humidity.7

Farmers all over the country suffered heavy losses, and virtually all crops were affected. For instance, durian harvests are down 40 to 60 percent, and coconut harvests declined by 80 to 90 percent year-on-year.8 A woman we know recently told us that, over the course of two months, more than fifty Durian trees died in the orchard she leases. She said that it’s like starting all over again – and that’s exactly what she will do. Borrow more money, and do the exact same thing, one more time, just with more chemical inputs to maximize growth & yields and (hopefully) make up for the losses.

Where is “rock bottom” when we need it?!

The economic consequences of the extreme drought earlier this year are just starting to be felt, and it’s going to be an extraordinarily tough year for the agricultural sector – overshadowed only by the increasingly precarious situation of the Thai economy at large. Household debt levels are already concerningly high (over 91 percent of GDP, the third highest in the world), and the Thai stock market is currently one of the world’s worst-performing. The government’s main obsessions are attracting foreign investors and high-spending tourists, “soft power,” random online rankings of food and travel destinations, and the implementation of a digital cash handout to appease the plebs. Meanwhile, Thai farmers are facing an ever-bleaker future outlook, and growing desperation has started to seep through the countryside.

At the heart of it lays a stark but mostly unspoken realization:

Industrial agriculture is failing. Every year is worse than the last.

Fortunately, our garden is doing pretty good. Surprisingly good, actually.

Even during the hottest year on record (so far!), we didn’t suffer any immediate losses. Our young fruit trees survived, most of them without any watering at all. Even most of our vegetables managed to pull through, although the April heat demanded harsh tribute. Most importantly, our pond didn’t dry up (more on that in Part Two).

If this is what a “Post-1.5°C World” looks like, in terms of immediate environmental impact many of our initial worries were unfounded.9 But a Post-1.5°C World is simultaneously a Pre-2.0°C World, and this line of thought gets really scary, really fast.

We actually prepared for forest fires early in dry season, cutting a fire break into the dense chaos of wild bamboo on both sides of our land that border on the forest, and removing potential fuel (which we turned into biochar) from deeper within the thicket. There already was a wildfire once, about 25 years ago – the one that destroyed much of the original forest cover of the hills that lie behind our land, and left it in a severely degraded state.10

Fortunately for us, the fires never materialized. Again, not yet.

But just like the last El Niño in 2016 was immediately followed by torrential downpours that flooded our outdoor kitchen until the propane gas tank floated and fish swam in the knee-high water around the fridge, this year’s rainy season did not hold back. Instead of a gradual transition into wet season with slowly increasing overall precipitation, the shift was swift and brutal. From one extreme into the next, like flipping a switch, instead of turning a dial.

And while we were carefully optimistic in the first half of the year, since the rains have arrived we’re in full survival mode again. The earth floor under the house is wet & slippery, laundry takes a week to dry, ants and termites invade our house incessantly, we fight runoff and erosion on a daily basis, worry much about our rabbits and chickens (see Part Two), and it is possible that part of the access road to our land will collapse after a few more heavy showers.

So, although it seems we’ve already quietly crossed over into the “Post-1.5°C World” (that officially wasn’t supposed to arrive before the next decade), we’re still here, planting, harvesting, eating, pruning, swearing, digging, laughing, draining, carrying, sweating, cutting, and – underneath everything else – waiting. Waiting for something to happen, some crucial part of the system to give in, some tipping point being reached that finally ushers in the next phase. Suspended in between two worlds, in the strange space where people pretend that everything is normal while the old world falls apart around them, the anticipation becomes almost unbearable at times. We don’t even know what exactly it is we’re waiting for, but the sheer uncertainty we’re facing is truly unnerving.

I think that on some level I’m simply waiting/looking for confirmation, for yet another unmistakable sign that it’s really happening, that it’s not me who is crazy. Last year it wasn’t this bad! Right?!

But in recent months, I’ve further dialed down (social) media use, because I found myself prone to forming habits that clearly qualified as “doomscrolling.” Each time I checked the news or scrolled the Feed, part of me expected to stumble on the next big article saying “Finally, collapse has arrived in full force. Things will not be the same again after this event. Yes, it’s all happening, and it’s happening now.”

Every now and then I did indeed encounter an article like that (or wrote one myself) – and yet things continued pretty much as they used to after I finished reading it. Our paleolithic brains have a hard time processing and integrating all the novel threats & supernatural stimuli into a coherent worldview.

Collapse is a painfully slow process for those living through it.

Teeth clenched, we grin and bear it. It will be a difficult year, no doubt about it, but so far we’ve been spared any real problems – although I don’t feel too comfortable saying this knowing that we still have to weather at least two more months of heavy rain, and the images we’re currently seeing from other parts of Asia are highly worrying.

“Well, at least we don’t starve!” we always say when we come back from a round through the garden, drenched to the bone but with our basket full of food, and “at least we don’t drown,” we add when the runoff trickles over the dirt floor of our open kitchen.

Money makes the world go ‘round (until it doesn’t)

One thing that’s for sure is that gardening in a Post-1.5°C World is becoming less profitable by the year. Returns are diminishing quickly, and even permaculturalists and regenerative farmers ultimately aren’t safe.

One of the main goals of our project is to reduce our dependence on the techno-industrial system, and the most important aspect of this endeavor is to eschew money as much as possible. The more you earn, the more you spend, and the more you spend, the more you’re tied to the system.

Joe Hollis wrote in his memorable 1992 essay “Paradise Gardening”:

The eschewal of money has a deeper meaning: money is the ‘blood’ of civilization, and the amount of it that flows through us is a direct index of the extent to which we are a participant, both depending on and supporting civilization.

Consequently, our goal is not to make as much money as possible but to make do with the least amount of money possible – an approach that’s obviously not entirely without risk. So far this strategy has paid off (no pun intended), but we have also come to understand how more financial security can bring a certain peace of mind (as long as the system still functions, at least), an abstract sense of security that we are currently denied. Our “health insurance” is based entirely on prophylaxis, so instead of paying an insurance company we take matters into our own hands, following the logic that “prevention is better than cure.”

But, as a matter of fact, right now – no matter how you live – you still need a certain amount of money, some sort of income, at least if you wish to remain connected to the rest of society to some degree. And as the system has diligently homogenized the world and exterminated alternative lifestyles in the process, people like us find ourselves in a bind. Financial pressure is increasing, while incomes flatline or even decrease.

From the beginning on, this project has stood on shaky financial foundations, and especially the initial phase would simply not have been possible without financial support from my side of the family and material support from my wife’s family’s side.11 In contrast to most others who take this path, we decided to start early in our lives, even though that meant that we wouldn’t have savings to draw from. Every natural farmer and permaculturalist we’ve ever met lamented that they didn’t start earlier, so we thought we’d somehow make it work, at the very least due to our strategy of radical expense-slashing when money is tight.

There are times when we live on a budget of 500฿ (around $15) per week,12 and life isn’t even that terrible. By now, we are able to survive off our garden. But life is about more than just survival: there is a long list of equipment & materials we’d like to buy before supply chains rupture, we have family members in need of financial support, a student loan to repay, and sometimes we just want to treat ourselves – so we’re by no means completely free of financial obligations & ties to the market economy.

And while we would most certainly love to live in a moneyless society with exchanges based on a traditional gift economy, this is simply not a possibility right now, not as long as the financial superstructure is still able to maintain its tight grip.

So the eschewal of money is not only an ideological practice for us, it is a perpetual necessity.

Making even a modest financial profit off the land has proven more difficult than expected. The soil is recovering, but still far away from fertile garden soil. Consequently, vegetable harvests are abysmally small & meager compared to what would be marketable (but finally enough for two people, after over five years – see Part Two of this series), and fruit harvests have declined drastically over the last three years due to averse weather conditions. Our main cash crop, mangosteen, failed for the second year in a row.

We are too far off the beaten track to receive a steady flow of visitors, and the extreme rainy seasons here mean that for a third of the year visiting us is simply not an option, so the whole farmstay/internship thing is at best a slight seasonal windfall, which is immediately reinvested into the project.

The regular sale of any other product (dried goods, seedlings, etc.) is limited by the fact that we live too far away from the nearest post office to allow for regular runs – plus we don’t have a car, which disincentivizes frequent trips to town during rainy season.

And even our fabled berry wine probably won’t become a golden goose. Just as we sold the last proper bottle, the next round of berries turned ripe. But this year’s harvest is disappointing, to say the least. Last year, we harvested & processed over 50 kilogram of Antidesma montanum, a wild berry that makes excellent wine (and vinegar) without the need to add yeast, fermentation stopper, or any other additives besides sugar. But due to this year’s extreme drought, only few flowers developed into fruit – so we got a mere four tanks (5 gallons each) this year, compared with eight tanks, amounting to over one hundred bottles of wine, last year.

As soon as the rains finally arrived some of the trees fruited a second time, but since there was basically no sunshine by then, few of the berries turned black, which will likely affect the quality of the last batch as well.

Last year’s harvest was promising, and the entire vintage was gone much faster than we’d expected. We didn’t even start advertising in any conventional way, and just by word of mouth we were able to reach a small but enthusiastic customer base. To be fair, this year we gave away more than half of our wine for free, as gifts to friends, relatives & visitors, in an effort to “spread the word” and gain customers who appreciate our product. Considering the upfront material costs,13 profits were marginal but nonetheless more than welcome.

But it looks like we won’t be able to deliver on our promises for the coming vintage.

First mangosteen, then wine – it seems that every time we think we finally have a reliable additional source of income, climate change comes and thwarts our plans. We will still have more than enough wine for ourselves (we only drink a bottle on special occasions like birthdays) and for our friends & family, but profits will be much more intermittent than initially anticipated.

Which brings me to the last point (for now):

Many thanks to you!!!

A heartfelt Thank You to you, dear reader, because it is your support that enables the wild experiment we’ve embarked upon. If it wasn’t for your feedback & encouragement, we would get very little recognition for the work we’re doing here, despite its relative importance.

And, since doing so is also long overdue, I’d like to give a special shout-out and extend my deepest gratitude to the dozen-odd people who’ve opted to become paid subscribers and supporters on Patreon. As it turns out – to my own surprise – my writing has become the most stable source of income we have, and what we do here simply would not be possible without the steady trickle of financial support we’re so gratefully receiving.

Although my writing is far too intermittent, weird, long, and niche-specific to push further monetization of this blog any more than I already do, I nonetheless hope to gain a few more paid subscribers, Patrons & donors over the coming years.

And, to be completely honest: we could need your support. We’re managing, but things have gotten harder, even for us. The rising cost of living is starting to affect us as well, and we find ourselves ditching more non-necessities from the weekly shopping list and allocating our budget towards the absolute essentials. This is what collapse looks and feels like in its early stages, and we’re by no means immune to its effects.

Gardening in a Post-1.5°C World is difficult, but ultimately still doable – yet it would simply be impossible without the help of a community. Optimally, this community would be our immediate environment, neighbors, friends and family, but since the system has worked relentlessly to tear apart families and uproot & divide real-world communities, the best substitute we currently have at our disposal is still the loosely connected and often anonymous “online community,” which, if you’ve read until this point, includes you as well.

From the bottom of my heart, Thank You.

Conclusions & Future prospects

The longer we live in relative isolation here on our mountainside, and the more we think about it, the more obvious it becomes that two people are not enough to weather the coming storm. During the first years here, we were able to distract ourselves with hard work and the exciting novelty of everything, but once the base of our Pyramid of Needs is laid, we long for meaningful connections to the people around us, a bit of social standing, and regular opportunities to socialize.

As of now, we can still use the internet to compensate for this need, but in the long term we will have to find ways to build friendships, forge alliances and recreate real communities locally.14

And perhaps that is what we’re actually waiting for: another part of the Inner Void finally being filled.

Until now, what stands in the way is the the war-against-Nature mentality among virtually all the people around us, and the horrendous amount of pesticides used to eradicate everything people can’t sell. We simply can’t pretend to be friends with people who think herbicide-yellowed lawns are beautiful, insects need to be categorically exterminated, and the only thing about food production that matters is how much money you get.

Farmers are unable and unwilling to give up the old ways, and they will stubbornly continue the futile struggle for a few more painful years. The outcome is clear already: they are facing utter ruin, and somewhere, deep down, they know it.

But in the meantime, no matter how much they try not to think about the future, panic is spreading.

The consequent toll on society and the land has reached Sysiphean proportions. Local administration budgets are strained already, and each new flood causes more damage. After each heavy downpour, parts of the dirt road network in our village need to be excavated, flattened, filled in, or reinforced. A fleet of small and medium-sized excavators are busy constantly in between floods, repairing the damage of the last rain before the next one arrives. Each time, they pile up more soft, red mud – and each time, their entire work is undone within a few hours, while a few more tons of soil wash away.

It’s not only us who are in “survival mode,” it’s the entire village, the entire district, province, country, region – and soon the entire world. Some of the more privileged ranks of society just haven’t realized it yet.

And whereas I have long given up on all the “dreams” I used to have when growing up, for most people this daunting task still lies before them. They still cling to the materialist fantasies advertised by the dominant culture, the promise of a “better life” if they just work hard enough. The Western middle-class lifestyle has been paraded around in front of people’s faces long enough for them to believe it is their right to achieve it, no matter the cost. Boy, are they in for a surprise.

My new dream is more modest, and more in line with what has been the standard for the vast majority of human history: to be able to live a reasonably peaceful life (without sustaining major traumas), spend time with my loved ones, and die a sudden and painless death before becoming a burden to anybody. I hope that’s not too much to ask from Life.

Again and again, I have to think about the farmers in the Dust Bowl, desperately plowing their fields in between dust storms, with each consequent storm turning neat rows into rolling dunes again, in. What else are we gonna do? We got mouths to feed, bills to pay…

History rhymes.

So we continue to wait. We wait for people to learn their lesson, for the fuel supply to tighten, for pesticides to become unaffordable, for markets to localize, for things to simplify and to get harder in some ways – but easier in others.

Stay tuned for Part Two — out soon!

It might not seem like much, but every new benefactor makes a big difference for us. If you happen to appreciate my writing and have a dollar or two left at the end of each month, please consider becoming a regular supporter:

Alternatively, you can support my writing (and our work) with a small, one-time donation:

For new subscribers: Rewilding Updates are a category of posts on this blog in which I share thoughts, reflect on experiences and recount what we’ve been up to at our permaculture project in Eastern Thailand.

What people don’t know yet is that they’re probably going to pay a lot more for the fuel for their water pumps in the coming years, as demand continues to climb, production declines, and profit margins for farmers are reduced even further. The profit margin of durian farming is already much smaller than it used to be just a few years back, and soon the only ones that are able to make moderate profits are the massive, mechanized & automated high-input monocultures lucky enough to be located in decent conditions and large enough to absorb the shocks of repeated bad harvests. Smallholder durian farming is losing its viability in front of our eyes.

Another such myth is that “fruit trees actually like red soil!” – a common trope invented by chemical manufacturers and parroted by farmers throughout the developing world (who sometimes add that “at least red soil doesn’t erode” when they spray herbicides). No! Just like any other tree, durian and other fruits prefer dark, rich, well-drained forest soil! The red clay that’s become so ubiquitous throughout the tropics is actually the sub-soil, the infertile, hard layer beneath the arable topsoil! Durian can survive in red soil, true – as long as you supply irrigation, fertilizer & pesticides. And that’s precisely the point.

We wake up at sunrise every day, so around 9:30pm we usually get so tired that we have to go to bed. Since we eat dinner between 7:00 and 8:00pm, there’s simply not much time for movies, so we had to watch it in 30-45 minute chunks over several days.

There was even a woman, Caroline Henderson, who “blogged” about the whole thing in a regular newspaper column. She had moved to the Oklahoma Panhandle before the Dust Bowl with romantic notions of living off the land while writing about her adventures, but soon found herself documenting the unraveling of her beloved new home and habitat. I can empathize.

We have no real reason to believe that this time things will be all that different, and apart from growing in scale & intensity, the dominant culture’s mission hasn’t changed much since then. What’s in our favor is that there is much greater awareness of ecology, the global environmental catastrophe at large, and hence our shared fate (at least among a growing part of the population), which will hopefully raise the bottom a bit.

Since it’s a “royal project,” any criticism – even questions regarding its effectiveness! – is technically against the law. Many Thais still believe that their last king actually invented cloud-seeding, and made agriculture in the more arid parts of the country feasible – the result of a colossal propaganda campaign spanning several decades. In fact, cloud-seeding has dubious success rates (at best!), and the arid Northeast is lacking rain because of centuries of deforestation. Nonetheless, airplanes circled overhead for the entire month of April, dumping countless tons of salt onto the land – with literally zero success rate. Even more astounding, they continued flying for weeks after the monsoon had already started, presumably to prop up their success rate on paper through seeding on rainy days and logging this as “success.”

There have even been persistent shortages of single bananas (individually wrapped in plastic, of course) that are sold in 7-Eleven – one of the best-selling items of the franchise.

I am aware that the 1.5°C threshold is pretty much arbitrary, I’m merely using common terminology here.

If you happen to have the credentials, connections and motivation to start a reforestation project with us, hit me up. The Rangers won’t let us do it if there’s no fancy organization or person with academic titles involved.

Thanks to my grandparents’ generosity (and perhaps pity?) we were able to purchase our small solar PV system and two new drinking water tanks. And without the biannual shipment of pesticide-free rice from Karn’s parents – in exchange for labor (Karn helps with the harvest and sometimes the planting) and fruit surplus (at least before the last two years of diminished harvests) – we wouldn’t have been able to sustain ourselves. Karn’s family also gifted us with a few regular household items that we lacked in the beginning (bowls, plates, woven baskets and containers from bamboo, old clothes etc).

Which, interestingly, happens to be pretty much exactly the international poverty line, rated at $2.15 per day.

Tanks, fermentation lids, sugar, corks, bottle caps and labels - we recycled the wine bottles from a restaurant, but paid Karn’s sister fuel money to deliver them to us.

We’re still hoping that one (or more) of Karn’s siblings come to live with us once city life becomes unbearable, but we might be forced to make other arrangements on short notice. Compromises will need to be made.

I think community is the most underrated and most difficult to achieve in this permaculture/homesteading/self-reliance thing. Both from practical considerations (maintaining a road for two people vs a village, sharing meat from a big animal vs storing, etc) and social needs. Ask me how i know. We are a nucleus family homesteading and we are so glad my wife's family is within driving distance. The plants and animals will grow with some physical and mental efforts, but try putting a group of people together...

I tried to make a one-time donation but the website doesnt accept anything from Malaysia. Do you have a thai bank account? Or other options?

it is surreal to wait for things change enough to wake people up. like, how bad does it need to get??

I worry, though, that -

a. in the medium term, the "updated paradigm" could look like blame and hostility instead of enlightenment (I live in an "intentional community" where some neighbors have been monitoring others' package deliveries to shame them for consumerism- as if that will change our fate, when really it's a way for them to project anxiety)

b. in the long term, Taker culture is so stubborn that it'll continue to insist "we could've made this work IF ONLY we'd implemented fusion energy (etc) sooner", never recognizing the spread of "development" as the core problem. It sets itself up for those kinds of excuses