The End of Bananas & Dwindling Diversity | Rewilding Update

Feun Foo Permaculture & Rewilding Update (November 2024) --- [Estimated reading time: 20 min.]

This is the latest installment in what has become a series of – dare I say monthly? – well, let’s call them semi-regular updates about what happens with our permaculture project, paired with some reflections and general observations.

The current Update was supposed to go online last week (hence “November”); my writing has stagnated a bit over the past few months, mostly due to an increase in garden work and the preparations for an upcoming family visit. I hope to catch up next year – there are plenty of drafts awaiting their final polishing!

What a tumultuous time we find ourselves in! All things considered, 2024 has not only been a challenging year, but a truly humbling one. Many things we thought we had figured out turned out to be more complex and/or complicated than we expected, and many things we were sure we knew and understood were refuted swiftly by the chaotic acceleration of global civilizational collapse and the breakdown of once-stable weather patterns.

The implications of the many concerning trends we’ve witnessed over the last few years are mildly horrifying, to say the least. It has become clear that, going forward, we can’t be sure of anything anymore.

The End of Bananas (?)

A prime example are bananas: we used to be dead sure that bananas (in their unripe/green form, boiled like potatoes) will be one of the universal future champions of tropical food security, which they undoubtedly will be – but perhaps not everywhere, not all the time, and quite likely not for us. At best, it seems, they will be a seasonal addition to our diet, another temporary pillar propping up an increasingly monotonous diet.

That bananas are so widely available today is a miracle in and of itself, and not a small one. Given the immense infrastructure required to ship bananas from plantation to supermarket shelf, the most surprising thing, perhaps, is that they are sold so cheaply that one wonders how any of this is profitable for the growers. Part of the secret is, of course, economies of scale – and hence the ruthless exploitation of both land and labor.

When viewed on the macro-level, it becomes clear the general state of the global banana industry is already a lot more precarious than most consumers know, and has been for quite a while. Over the past decade or so, thanks to a number of documentaries, reports and articles about the issue, more people have become aware of the sword hanging over the commercial banana industry: Foc TR4,1 commonly called Panama disease. This mostly invisible fungus literally wipes out commercial plantations and wreaks havoc in both local ecology and economy, making the land unsuitable for continued banana cultivation in only a few short years after infection. The exact same thing had already happened to the “Gros Michel,” the previous main commercial cultivar, in the 1950s before it was replaced by the Cavendish – but, as so often, commercial farmers haven’t learned the most obvious lesson from their past mistakes.2

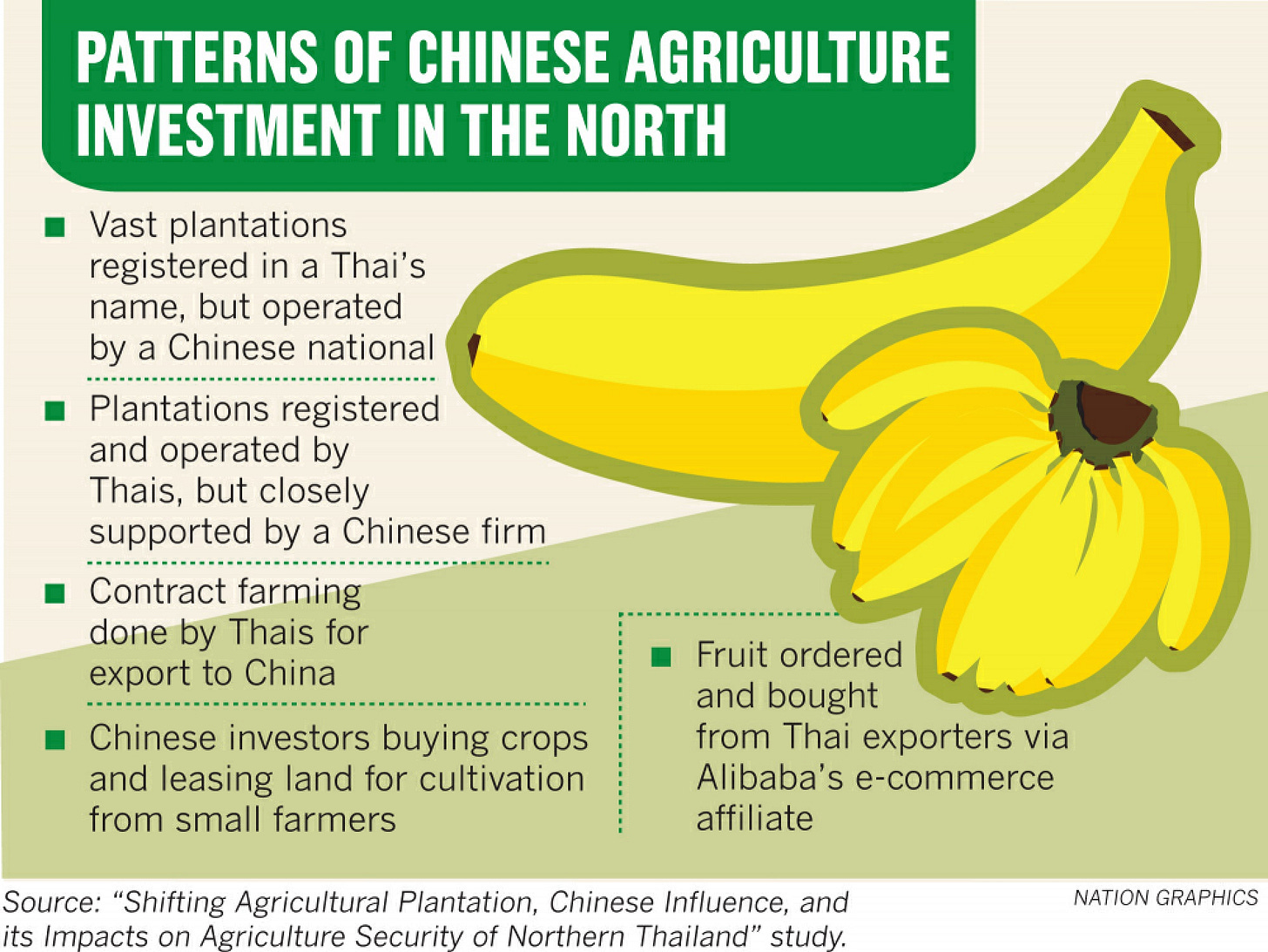

Right beyond the northern border of Thailand, banana growers in Laos are starting to face serious problems from Panama disease. In the small, landlocked country a lot of Cavendish is grown on massive plantations for the insatiable Chinese market, and a quiet land grab has been happening for several years, hand in hand with what can be best described as modern-day slavery.

Vast tracts of land are leased by Chinese companies, who establish massive banana monocultures. The workers – often married couples from other provinces3 – sign contracts for one season, live in shabby little slum huts right in their designated patch of the massive banana orchards, have to handle the most toxic (and often unregulated) pesticides without being able to even read the instructions (which are often in Chinese), and get water for household use from chemical runoff-polluted streams bordering the plantations.4 They are not allowed to leave the premises, but are instead forced to buy their groceries & essentials at Chinese-owned company stores at exorbitant prices, and any transgression of the rules can invite physical punishment by the Chinese overseers. Those “company (shanty)towns” have become more and more common throughout the region, and we are already seeing this trend spilling over the border into Northern Thailand as Chinese economic influence increases through their various neo-colonialist enterprises – China requires its bananas!

“Over the past two years [2016-2018], Chinese investors appear to have invaded provinces in the North, such as Chiang Rai and Phayao, to grow Cavendish bananas after the practice was banned in Laos. Locals and NGOs, however, have voiced concerns about Chinese-run plantations using pesticides excessively and giving rise to conflicts over water.”

[The temporary ban on new banana plantations in Laos has since been lifted.5] (Source)

As a matter of course, the dreaded fungus has already crossed the border a few years ago, closely trailing the Chinese expansion. Preventive measures against the spread of TR4 are exceedingly difficult to implement, so the most common strategy is to simply plant bananas until the fungus inevitably starts impacting profits, and then move to a different place and do the whole thing all over again. Driven solely by profit, people are burning through fertile soil and leaving an ecological wasteland soaked in pesticides. Not exactly long-term thinking, but what else can we expect from the “business mindset”?

For now, Panama disease and other fungal infections mostly threaten large, industrial-scale operations, and just a handful of varieties out of hundreds. Home gardens and mixed orchards are much safer, as there is more space in between banana plants that prevents the spread, and more fungal diversity in the soil that might be able to outbalance the few dangerous species.

But diseases are not the only growing problem the banana industry faces: tropical storms (of which we had a few intense ones this year in the region) regularly flatten countless hectares of banana plantations and thus lead to massive losses, as did the severe floods in Northern Thailand a few months ago.6 While the banana plants themselves don’t die, it takes several months for them to recover, produce new suckers (shoots), and resume fruit production. In some places, the plantations recovered just in time for the next big storm to reset the clock again.

Again, this problem mostly affects large plantations, as mixed orchards (such as ours) have other trees planted in between that act as a windbreak. Even during strong storms, very few of our banana plants actually fall over or break.

But even long before the unusually stormy monsoon started, the banana shortage this year made itself felt in the strangest places: scores of consumers complained online that there were no bananas in 7-Eleven (they usually sell single Cavendish bananas, individually packed in a plastic bag, of course), as strained supply chains led to delays and shortages nationwide.

Strangled by the extreme drought in this year’s first two quarters, banana plants drastically decreased fruit production for several months. Prices of the popular “Nam Waa” variety (also called “Pisang Awak”) soared from 20 Baht to an eye-watering 80 Baht per hand in some cities, and a consequent ripple went through local businesses dependent on bananas. Grilled and deep-fried bananas are sold on every local market, and they temporarily turned into a luxury food.

So while Panama disease is a problem directly related to the scale of cultivation, storms, droughts and other extreme weather events can also impact smaller orchards and home gardens, and this vulnerability became painfully obvious this year.

But in our small forest orchard the rapid oscillation between weather extremes wasn’t the only stressor for banana plants over the past few years.

The banana stem borer is an unsuspecting but beautiful little beetle, with a long snout that looks a bit like the trunk of an elephant. We have no idea what they do for the rest of the year, but in rainy season the females lay eggs into banana shoot stems, preferably those with smaller diameters, and especially the weaker ones called “water suckers” in industry parlance.7

The first sign is a transparent, jelly-like substance oozing out of the sucker – a desperate last attempt by the banana plant to flush out the intruder that is not often successful. Almost immediately, the tiny larva starts burrowing towards the center of the stem. Once there, the feast begins: as she works her way down the very middle of the stem, she consumes the tender innermost leaf, the part of the banana (pseudo-)stem that we often use to make salad or eat as a vegetable. The little grub grows fast, and once she reaches the bottom, she can be thicker than a pencil. Before entering the corm (the round, hard rhizome of the banana plant which is not infrequently the size of a basketball), she seals the tunnel behind her good, so that adventurous ants can’t follow her.

Then she digs in. Banana corms contain plenty of starch, so – after the salad – what follows now is the main dish. As she works her way through the corm in winding tunnels, she becomes more and more sluggish – the next part of her life is dawning. Once she can’t possibly eat another bite, she starts pupating. She stays in this otherworldly dream state, in between to ways of being that couldn’t be more different from one another, for about a week. Afterwards, the final stage emerges: a still soft and brightly colored stem borer. She escapes into the soil, digs her way towards the light, and emerges into what we call “the World.” The feeling must be indescribable – like being born a second time.

As fascinating, inspiring and envy-evoking as this story is, the little bug has caused us plenty of headaches this year. More than half of the banana shoots we planted this season didn’t make it. Most succumbed to the inconspicuous little red-black beetle. The attacked suckers will stop growing immediately, and one of the first signs of an infestation is that the emerging “cigar leaf”8 stops moving. Usually, you can literally watch bananas growing, at least during the time a new leaf emerges or when they flower.

Banana stems push out new growth at a rate of up to several centimeters per day (if conditions are good), but as soon as the stem borer larva reaches the center, this process is immediately arrested. The only thing left to do now is to heavy-heartedly chop down the entire infected shoot in segments, starting at the very top, until you reach the larva.

I have recently written about diminishing returns agriculture, and one example I gave was that farmers have to spend more time counteracting the effects (i.e. problems) caused by the accelerating collapse of the biosphere. The returns on our work (planting bananas) have been diminished greatly this year, as we had to re-plant all infested banana shoots. Most of them will manage to produce another tiny little sucker if left unattended, but – having used up most of their energy reserves on the first try – they will have a much harder time growing strong, so it makes more sense to start over and just plant a new shoot.

It got to the point at which we didn’t have enough new banana shoots to replant, as all surplus shoots were either already planted or destroyed by stem borers. Optimally, each banana cluster should have three or four stems, of various sizes. We can only dig suckers if there’s excess available, lest the plant takes a whole lot longer to grow, and thus fruits less frequently. So we prepared new holes while we waited for the new shoots to grow, but since the rains have abated over the past few weeks, it seems we missed our window for this year.

We might attempt to plant more banana shoots in the coming dry season, when stem borer attacks are less common, to make up for the losses. But this means yet another increase of our workload, as we have to water the freshly planted shoots at least once a week, further diminishing the EROI.

Maybe this is just a temporary ecological imbalance (of which we have experienced quite a few in the past years), and one predator or another will become more abundant in return, but maybe the problem is here to stay.

Until then, there’s only one way for us to fight back:

Again, all banana cultivars are a product of the stable climate of the Holocene. Only wild bananas have survived both a lot longer and a lot worse. And, indeed, the wild bananas seem to be doing fine. They get attacked as well, but not as often (their shoots are more plentiful, much tougher, and they grow more vigorously), and they seem to be able to seal off infested shoots much faster, thus preventing the larvae from boring into the main corm.

So, will we live to see the End of Bananas? Perhaps not, at least if you live in the tropics. In temperate regions, on the other hand, the End of Bananas is a very real possibility for the near- to medium-term future. And even in the natural range of bananas, it might very well be that the assortment we will end up with is a lot less diverse and abundant than what we’ve grown used to.

Just a few short years ago we were sure that bananas will be one of our main staple foods in the future, but the last two years have eroded our confidence in their universal viability considerably. Banana cultivars are genetically identical clones, and thus very susceptible to diseases. There are a few cultivars that appear to resist the steady onslaught of stem borers and flood-drought cycles better than others, usually more ancient types with strong genetics inherited from their wild ancestors. One type is the Saba banana (กล้วยหิน), another one is called “Hŏm Jampaa” (กล้วยกล้วยหอมจําปา). The ancestor of all plantains (Musa balbisiana; กล้วยตานี) seems to be resistant, but the fruit contains so many seeds that it’s edible but barely enjoyable.9

But even the hardy, highly nutritious local “Nam Waa” cultivar has been battered by repeated fungal infections in our garden (not Panama disease, but perhaps Black Sigatoka), and – over the course of a single year – turned from the most to one of the least frequent banana cultivars we harvest.

One upside of the “Bananapocalypse” this year has been that farmers throughout the region have started planting a lot more of the tropical treat (albeit motivated less by future food security and more by the promise of large profits).10 All over the area where we live newly planted bananas line roads and paths, and a few farmers have even started intercropping their fruit trees with bananas.11 Despite the various problems outlined above, this will hopefully result in a net positive, at least in the near-term.

In case of a sudden breadbasket failure, unripe bananas could still provide a much-needed buffer that helps soften the impact of greatly diminished rice harvests, at least in less densely settled areas. It will just be a whole lot more work than we initially thought.

Dwindling Diversity

Indeed, our diet as a whole will likely become drastically less diverse. Not only in regard to more obvious, store-bought foods dependent on (inter)national markets & supply chains, but also local produce.

Over the two wettest months (August and September), we lost all our long bean plants to fungal infections. Plant diseases of all sorts (but, due to the high humidity and precipitation here, especially fungi) have become more common over the past years, not only for us but also for virtually all durian farmers, who – despite regular heavy fungicide applications – saw their trees die in droves due to Phytophthora infections.

Moreover, we used to grow cucamelons for the first few years here, but after the triple La-Niña (2020-2023) we ran out of seeds. Cucamelons need plenty of sunshine and are surprisingly drought-tolerant, but they wither and die easily if it rains too much. They are now extinct from the area, as nobody in our immediate community cares to save their own seed.

Very few people grow vegetables in our province, and those that do mostly do it on vast commercial scales (using commercial inputs). All vegetable farmers agree that it is a lot more convenient to simply buy new (hybrid) seeds every year, and a cultural “focus on the present” (and concomitant disregard for the future) makes them oblivious to the potentially life-threatening consequences of allowing large agricultural conglomerates to dominate the seed market.

Over the past years of climatic extremes and erratic shifts in weather patterns, it has become painfully clear that only the strongest crops can hope to survive the current shift in the global climatic regime. Quite likely, the most common (and most productive) grain cultivars will not be among them. Most crops we eat today are very recent additions to our diets, and all of them were selected/bred for large fruit (and thus against drought- or disease-tolerance – you can’t have your cake and eat it, too). This results in weak plants producing nutritionally empty fruit, utterly dependent on an endless supply of irrigation, concentrated chemical inputs and toxic pesticides, plants that can tolerate so little climatic variation that they increasingly have to be cultivated in greenhouses.

Our personal seedbank has grown to a decent size (at least when compared with everyone else around us), but we’ve noticed some disturbing trends. There is more and more seasonal variability, and during the monsoon it is extremely difficult to save any seed at all. Rainy season here is a constant battle against mold.

So far, we haven’t scaled up the storing of seeds, but only saved enough for us and a handful of friends with whom we sometimes exchange seeds.12 It has become clear that this has to change. We will have to invest a lot more time and effort in seed saving, and put a much greater focus on obtaining as much good seeds as anyhow possible. Now the time has come for us to try our best to do so during the coming years, partly because we have slowly started receiving more requests for all sorts of seed. Apparently, at least a few people are starting to realize the immense quagmire we’ve gotten ourselves in. It might happen just in time.

But either way, we will be forced to say farewell to quite a lot of crops that we’d rather not lose.

Over the past century or so, we’ve lost at least 75 percent of global food biodiversity, and this staggering decline started long before climate change became an issue. It happened mostly due to market incentives prioritizing traits such as simultaneous ripening, easy transportability, reduced bruising while handling & shipping, and, of course, fruit size, uniformity, and sugar content. Factoring in climatic pressures and associated threats, it is highly likely that food biodiversity will be reduced even more over the coming decades, even if the economic superstructure responsible for the bulk of this reduction collapses soon.

The unusually stable Holocene climate was a precious gift, an opportunity to experiment with larger-scale societies and more diverse social organizations and subsistence modes – and we have squandered it. We have turned this one-time chance into a dystopian nightmare of epic proportions; we’ve ravaged our environment and trapped ourselves in endless dopamine doom loops as we transformed basic daily necessities & routines into commodities & services with the highest potential for addiction, because those calling the shots know too well that addicts are the most reliable customers.

Now all that remains to be seen is how quickly mass society will falter when confronted with sudden food shortages of increasing frequency and severity. So far, the Thai government’s head-in-the-sand approach gives little reason to hope for a lenient outcome. Just like their Big Brother to the North, officials straight-up ignore anything that might taint the positive image they so desperately promote in a bid to reassure the public and retain some sense of normalcy. Surreal articles and statements abound, like this gem from a recent Bangkok Post article (that could be straight from a CCP handbook) enthusiastically summarizing this year’s fruit season:

“The [Department of Internal Trade’s] 2024 fruit management plan, which involved six key measures and 25 initiatives, […] has resulted in a successful conclusion to the fruit season, marking another golden year for farmers, who have enjoyed high prices and increased income.” [Emphasis added]

Curiously, the entire article lacks any meaningful statistics that allow cross-comparison with previous years, but instead provides plenty of empty numbers that seem “big,” without any additional context. It entirely fails to mention this year’s record drought, the concomitant reduced harvests, or any other accompanying hardships faced by farmers.

Going forward, it is going to get harder and harder to keep up the cheerful official tone while society is crumbling all around us, and yet it seems like those running this shitshow are more obsessed with keeping up appearances than with figuring out actual responses to our predicament. Even after yet another year of record-breaking climate extremes and economic uncertainty, collapse awareness in the “Land of Smiles” remains abysmally small, and various cultural biases as well as a more general cultural rigidity (which I’ll elaborate on in a later installment) effectively inhibit the difficult but necessary conversations we so desperately need.

Some closing thoughts on (losing) hope

If there’s any underlying theme for this year, it is that 2024 is the year in which I finally lost every last bit of hope that things might, against all odds, still turn out better than I initially expected. No, 2024 will go down in history as the year in which whatever scant remnant of optimism I still harbored finally succumbed to its terminal illness, after endless years of suffering and dread.

What’s coming for us is not a mere derailment, it will be a head-on collision at full speed, explosions, barrel rolls and other special effects included. People in this part of the world are determined to continue with Business as Usual no matter what, and instead of slowing down, at this crucial point in time they are accelerating the rape and plunder of the Earth, the forcible conversion of the Living World into dead matter and imaginary wealth.

Not a single world about slowing down, reducing or reconsidering, let alone remorse.

Until recently, some part of me still hoped that there will be some sort of tipping point, a point at which things will become so bad that people will have finally had enough, at which the proverbial scales will fall from their eyes and they look around in astonishment, shocked that they’ve ever allowed things to get this bad.

But then I think about places like New Delhi, where just breathing the air is akin to smoking two packs of cigarettes per day, and the fact that people still go about their daily lives as if all this is normal. I think about the people living in Agbogbloshie, Ghana (lovingly called ‘Sodom’ by its inhabitants), and wonder if that’s where we’re headed as the baseline underneath us slowly shifts towards annihilation.

How many cigarettes-per-day equivalents do our children have to inhale until we finally admit that we have to bid farewell to airplanes, cars and factories, to luxuries and comforts, and to empty promises of living lives like the people on TV? The answer is “definitely more than five (Bangkok on a bad day), and quite likely more than fifty (New Delhi on a bad day),” which is to say “if this means that we have to admit to ourselves that we were wrong, that everything we did so far was for nothing, fuck breathing – let ‘em chain-smoke instead!”

But maybe I’m wrong. Damn, I do hope I’m wrong – but does that mean that I still have hope after all? Or is it just an empty phrase people say in dire situations? Maybe a revolution (or similar disruption) is just around the corner? If anything, they are notoriously difficult to anticipate.13 But as long as there’s ample shortcuts to circumvent our brain’s reward system, chances are slim. As I’m fond of saying, without social media and junk food – “scrolling & sugar” – the revolution would have happened already.

So what does all that mean for our personal rewilding journey? Maybe what we’re doing with our land project is more than yet another version of escapism, more than drops of water on a hot stone, but it increasingly seems like just that: violins on the fucking Titanic.

Yet tending our garden, mixing soil and planting trees like lunatics even in the face of ecological disaster is the only activity left that helps us remain somewhat sane. At least we’re doing something to counteract the steady degradation of the ecosystem, and no matter how futile those efforts are in the bigger picture, they make us feel less shitty.

After a good day’s work in the garden the world doesn’t seem so bad.

So perhaps this is it: gardening beyond hope, my personal pre-apocalypse obsession. But what I’d like to do with the limited time we’ve got left is not skydiving, traveling, bungee jumping and partying, but to continue to help the myriad beings around me, the ones neglected by everyone else. If not us, then who will do it?

Again, I am reminded of the stubborn relentlessness of the sand bubbler crab, arranging tiny pellets of sand in delicate circles before the next high tide washes it all away again. She knows the waves are coming, yet she spends hours to create beauty, day after day. There are countless ways to look at it – perhaps it is an allegory for people rebuilding cities and civilizations again and again after each collapse, until raising sea levels swallow up the beach.

But maybe the crab just does what needs to be done. Maybe she just follows her Nature – the Tao – and plays her designated part in the Greater Scheme of Things. Knowing full well that those efforts are ultimately futile, she nonetheless creates doomed beauty while obtaining sustenance from her immediate environment.

Maybe the ultimate outcome doesn’t matter as much as the act of doing what needs to be done – of doing what’s right.

At the very least we will be able to sleep at night and live with ourselves.

Or so I hope.

Previous Rewilding Updates:

I write stuff like the above in my free time, when I’m not tending the piece of land we’re rewilding here at Feun Foo. As a subsistence farmer by profession I don’t have a regular income, so if you have a few bucks to spare please consider supporting my work with a small donation:

If you want to support our project on a regular basis, you can become a Patron for as little as $1 per month - cheaper than a paid subscription!

“Foc TR4” stands for Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense, Tropical Race 4

Newsflash: monocultures are unsustainable! Apparently most farmers still haven’t gotten this message.

As every imperialist knows, migrant workers (who can’t fall back on their community) are less likely to cause trouble than locals. And the most money can be made off workers with the fewest rights.

The BBC reported that forty to eighty fungicide applications per growing season are not uncommon. (It’s the same for durian plantations where we live: on average, people spray their entire orchards at least once per week.)

Did Lao officials actually think they could force China to abide by local law?! China basically owns their entire country!

Floods are also a major vector for the spread fungal spores.

Healthy ones are called “sword suckers” – whoever came up with the botanical terms for banana plants was perhaps an old-school mafia capo.

Seriously, were the people who named banana plant parts some sort of cartel?

M. balbisiana was first cultivated for its starchy corms, perhaps as early as 10,000 years ago.

If they scale up too much, they will likely encounter the same problems that already besiege other banana growing operations: increasing applications of insecticides & fungicides, and thus decreasing profit margins.

So far, banana intercropping has not been very common because people are afraid it will attract elephants, and because farmers consider it a nuisance since it makes spraying pesticides more difficult (the rubber hose gets tangled up in the vegetation).

Unfortunately, we are the only ones of this small, personal network who are a) full-time gardeners, and b) actually serious about feeding themselves.

China remains the biggest wild card. Let it suffice to say that by far most people were taken by surprise when the Soviet Union suddenly collapsed.

Have you considered tracking down the parent fertile species of domestic seedless bananas and repeating the hybridisation to produce new strains? Could be a path to developing hardier locally adapted plantain strains in the future.

Our pisang awak is by far the most productive variety in our conditons. Do you have the seeded pisang awak? It is even more vigorous than pisang awak. The seeds are many and about the size of mung beans. I steam them and the seeds separates from the flesh cleanly in my mouth.

I have a sabar that just started growing, called pisang nipah or abu here. Seems big and strong.

Pisang kapas is quite ok too, and is the choice banana here to cook as a starchy vegetable. It tastes like the wild bananas here with big seeds.

Pisang asam (sour) is also quite vigorous and nice as a dessert banana.

I think these are the four that are common in the past in my region before chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and irrigation.