Has Agriculture reached the Point of Diminishing Returns?

Confronting a difficult truth: the Age of Agriculture is over --- [Estimated reading time: 30 min.]

A quick note to subscribers: For the sake of my own mental well-being and that of regular readers I usually try to avoid publishing multiple “doomer pieces” in a row, but the current issue is urgent enough for me to discard this rule temporarily. Also, the ratio of doomer pieces in my drafts is considerably higher as of lately, so I won’t be able to avoid publishing a little avalanche of doom every now and then. It is what it is.

It almost seems paradoxical, but there is no way to sugarcoat it: the longer we work the land on our small, mixed forest orchard, the lower the fruit yields of many mature trees – at least as a general trend over the years. This is especially true for the main fruit crops of our province, durian and mangosteen. Now, evil tongues might suggest that we just really suck at gardening. Yet our misfortune seems to be part of a broader a trend, neither confined to our own project, nor to the bioregion or climate zone we inhabit.

Last year was, according to farmers in the region, one of the worst years in living memory for both of those crops. The mangosteen harvest was an almost complete failure, and durian yields were reduced drastically year-on-year, despite the year before having already logged as subpar.

Fortunately for us, overall abundance (as in “net productivity”) is still slowly increasing in our garden, but just because the new trees we planted in the previous five years slowly begin to bear fruit.1

Last year, that fateful year when global temperatures went off the charts, was difficult for fruit farmers around the world. In the United States, Hudson Valley in New York state lost 90 percent of its stone fruit, while the neighboring state of Connecticut lost between 50 and 75 percent. Georgia, the “Peach state,” lost over 90 percent of its peach crop due to late-spring cold snaps, with some orchards experiencing losses of up to 98 percent. Simultaneously, South Carolina lost 75 percent. In New Hampshire, a cold snap annihilated apple blossoms, leading to failed harvests for many farmers in the area.

Meanwhile, cacao harvests in West Africa have been so low that the price of cacao jumped a staggering 200 percent within a single year, and, in anticipation of bad harvests in Thailand and India, the sugar price is expected to rise dramatically as well.

A recent article in The Guardian confirms that this is in no way limited to fruit farming: harvests of staple crops in England will decline due to averse winter weather and exceptional rainfall – some areas experienced the “wettest 12-month period since records began.” For months, flood waters stood as high as five meters in some places, and even farms that were spared from actual flooding managed to get no more than 25 percent of winter crops planted due to the unusually high rainfall.

“The forecasts for this year’s harvest look gloomy. The Agricultural and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB) is predicting that wheat outputs will drop by a quarter.”

And this is just the latest example. Due to extraordinarily heavy rainfall, Irish potato farmers were only able to harvest 40 percent of their crop in time last year, making it the “worst [harvest] in recent memory.” On the other side of the globe, Argentina lost half of its soybean crop to an “unprecedented” drought, marking a “disastrous year.” In India, severe flooding threatened harvests and led to an export ban on rice that made global headlines – a move that will exacerbate the unfolding global food crisis, since India accounts for 40 percent of global rice exports.

And the list goes on and on.

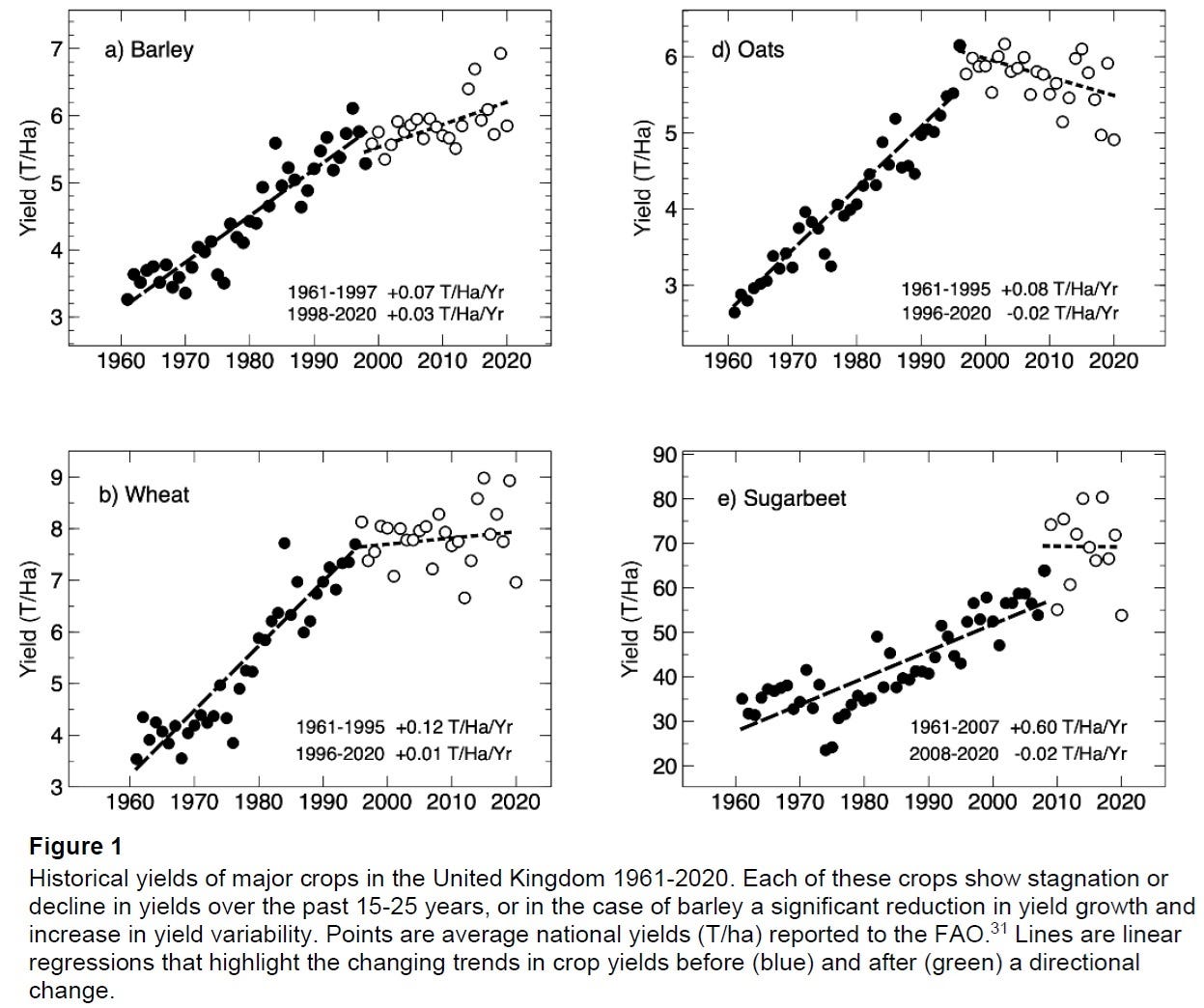

Alarmingly, all this seems part of a general tendency. The paper ‘Beyond fed up: six hard trends that lead to food system breakdown’ by Jem Bendell compiles data from Britain, showing that harvests of major crops have either peaked already or are about to peak in the coming years:

Even more concerning is that it seems like projects that apply ecologically sane, regenerative methods weren’t spared. As a permaculturalist by profession, I am in contact with a handful of similar projects from all over the world – and what I hear from other countries and continents sounds eerily familiar. Abnormalities abound: erratic and repeated flowering, as if the trees are confused about the timing and need to take several attempts; fruits that fail to develop properly and shrivel before they reach maturity; seeds that germinate within fruits still attached to the plant; produce that drops prematurely as if suddenly rejected by the plant. On top of reduced harvests and failed crops: fungal infections and sudden insect infestations, hinting at larger ecological imbalances.

But more on that in a minute. Let us first examine the main underlying causes: climate change and biodiversity collapse.

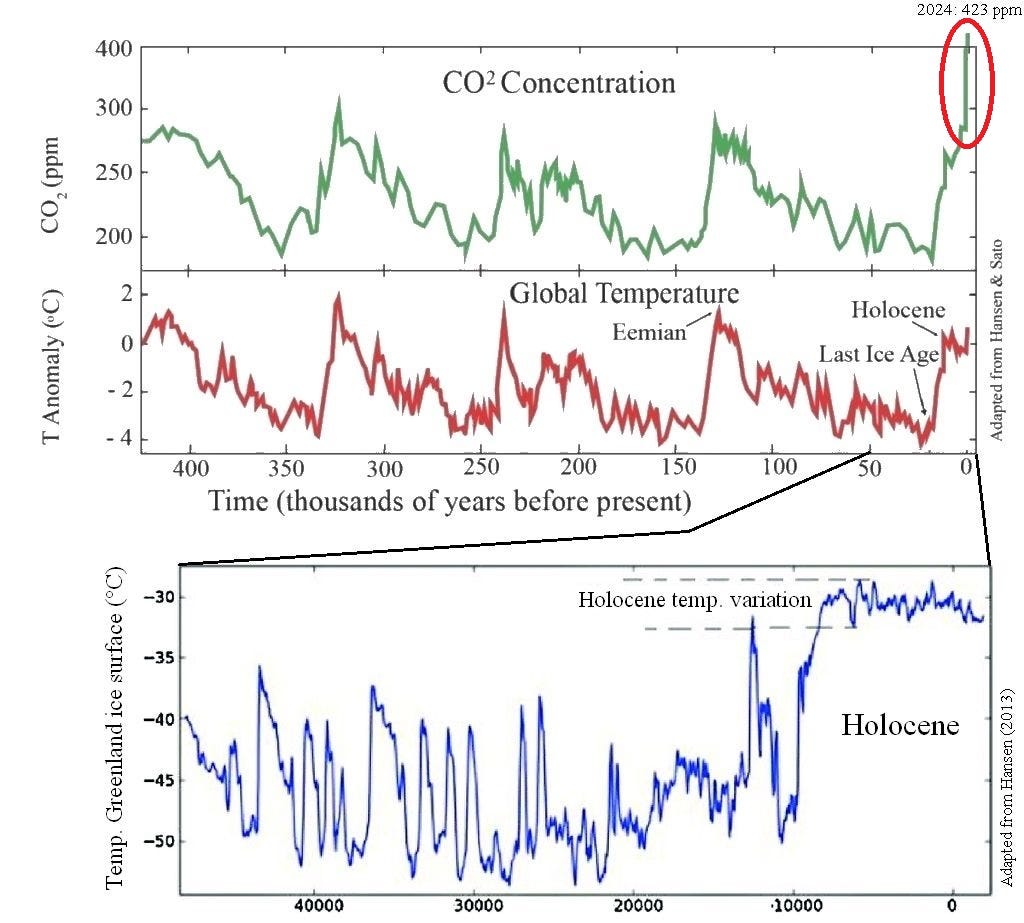

To the avid reader of this blog, the following shouldn’t come as a surprise. As I have pointed out repeatedly in the past, agriculture started evolving around 12,000 years ago, not because people suddenly figured out how a plant’s life cycle works, but because the global climate settled into a new, stable state – the Holocene – that allowed for sedentism and the first experiments with plant cultivation. Before that, an erratic and unpredictable climate made sedentism (and hence farming) a much riskier survival strategy than nomadic foraging.

Agriculture is only possible in a stable climate.

It has become obvious over the past few years that we’ve left the comfortably lukewarm Holocene and entered an entirely new chapter of the Earth’s climatic history – the (much hotter) Anthropocene. This new epoch will likely be characterized by equally wild swings in weather patterns as the Pleistocene that preceded the Holocene.

What we are currently witnessing is the beginning of the end of agriculture as a subsistence mode.

Yet virtually nobody talks about it in those terms. Very few people realize what exactly is going on, and the implications are so terrifying that many just choose to ignore the issue altogether.

Shifting Baseline Syndrome has become endemic these days. The creeping decay of infrastructure that plagues my country of origin, the general lack of skilled crafts(wo)men, the increasing slack of global supply chains cumulating in mysterious delays and ever-higher prices, the opioids seeping through US-American society, the inexplicable (often called “temporary”) layoffs plaguing factory workers in many parts of the world; everything happens gradually, over time, so people don’t necessarily realize how much things have deteriorated over the past few decades. And while all the aforementioned trends worsened steadily, we now also find ourselves quite literally in uncharted territory in regards to both the global climate and the effects this shift has on our own ecological niche.

Collapse is well underway.

Concerning the climate, we’re currently living through the worst-case scenarios of previous projections. Without even diving into the scientific literature, everyone following the news can recall how often the word “unprecedented” was used during the past few years, and due to the fact that it is often climate scientists themselves who say that everything is happening “much faster than expected,” it’s safe to say that warming is accelerating rapidly.2 This should come as absolutely no surprise, given that this is how exponential growth works: faster than expected.

When we look at the many “hockeystick graphs” that define the Great Acceleration after WWII, it becomes obvious that exponentially degenerating climate phenomena are just what’s to be anticipated, following the exponential increase in both various greenhouse gases and the destruction of ecosystems the world over.

What has happened over the past few years is that the baseline(s) started shifting so fast that changes became noticeable to more and more people. These days, you can literally watch wildlife numbers dwindle, although, as optimists unfailingly point out, some animals do seem to thrive: in the ecosystem we inhabit, it is mostly mosquitoes, cockroaches, certain mites and a few other nuisances.3

On our land, overall numbers of insects, birds, bats, lizards, snakes and frogs visibly declined in the past five years we live here, despite us living right next to a “Nature Reserve,” and despite our frantic efforts to create habitat and plant diversity. Even wild monkeys and elephants visit our garden less frequently. If everyone around you works full time on destroying the biosphere – eradicating habitat, eroding topsoil, moving mountains, burning off biomass and trash, and soaking the land in highly toxic chemicals – your own efforts don’t really matter that much.

Wild animals find themselves in a precarious position: habitat declines and deteriorates unabated, pesticides and other toxic pollutants saturate air, water and soil, and climatic changes influence their behavior and development – and all of those factors are currently accelerating and increasing in severity.

Anecdotes abound of staggering and often quite sudden losses of certain animal populations. Massive fish die-offs are becoming increasingly common, and even we haven’t been spared: just earlier this month, all adult golden carps (Probarbus jullieni) in our pond died overnight, likely due to a lack of oxygen and/or a sudden change in the composition of the water. Whether among wild or farmed animals, die-offs are increasing in frequency and severity. Salmon farms, for instance, are increasingly affected by catastrophic die-offs, and both climate change and disease outbreaks have devastated factory farms around the world.4

But there is another issue that’s been on my mind a lot lately, something that would provide an additional explanation to the general weakening of both animal and plant populations.

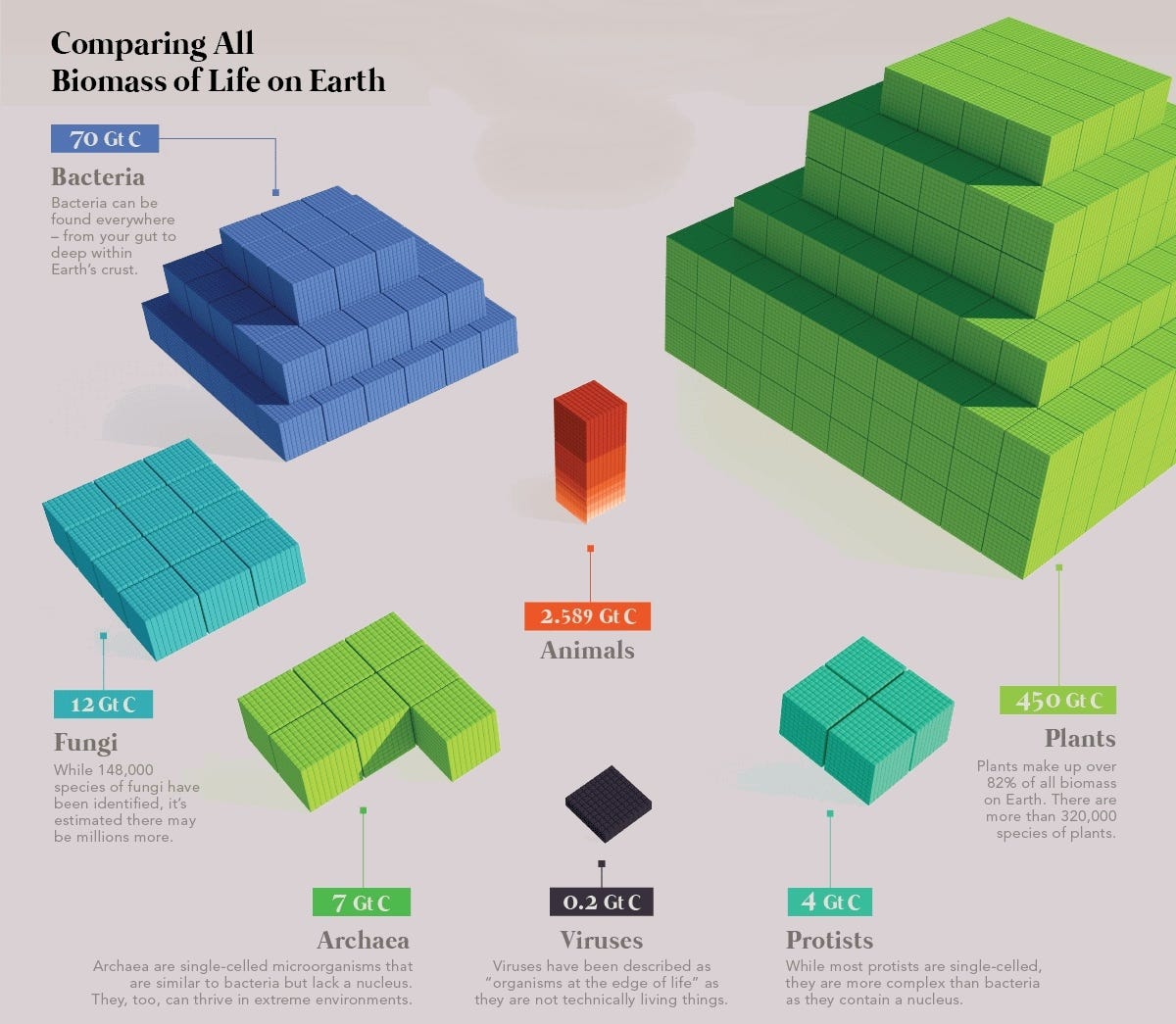

Bacteria and fungi, although often overlooked, are vital parts of all ecologies and fulfill crucial roles in the food web. In fact, their biomass greatly exceeds that of all animals combined: they form the very basis of all ecosystems. The reason I think about those organisms, ubiquitous but hidden in plain sight, is that they, too, seem to be heavily affected by drastic changes in their communities.

Because the last years were so wet, fungi had the time of their lives. Well, certain fungi did. One species of Phytophthora, a fungus that attacks and kills durian trees (and many other plants), runs rampant in orchards throughout the province we live in, and causes mature trees to die in a matter of mere months. For fruit farmers, this means a huge blow to their finances, since a productive mature durian tree can produce up to 200 kilograms or more per year – and with an average price of around 100 Baht (~$3) per kilo, each dead tree constitutes a substantial loss.5

Again, we’ve been affected as well: over the three-year-long La Niña, fungal attacks killed two large softwood trees close to our pond and the tall silk-cotton tree (Cochlospermum religiosum) right in front of our house. Then, earlier this year, we found the first diseased durian tree on our land.6 For two years already, we didn’t harvest any beans for the first four months of dry season, due to a wind-borne fungus infecting the leaves and causing them to wilt. And last rainy season, an unknown fungus killed five of our most productive “Nam Waa” banana plants.

Witnessing this trend firsthand has led me to formulate a theory with scary implications: when wildlife numbers, especially insects, are already in rapid decline, the same must be true for those organisms we can’t see. I suspect that collapse is well underway in microbial and fungal populations the world over, and that there are major ecological imbalances that can cause disease and early death in both animals and plants. Microplastics, pesticides, PFAS, tire dust, antibiotics – a whole panoply of highly hazardous persistent organic pollutants already saturate the biosphere and pose a threat to microbial and fungal populations.

There is abundant evidence that fungicides, applied in large enough quantities, permanently alter the composition of the microbial and fungal community – duh! – and that pesticides in general have deleterious effects on the soil microbiome, especially in the long term.

Another factor that is frequently overlooked is that antibiotics, overprescribed among humans and widely used in factory farming worldwide, have disastrous effects on microbial communities as well. Anywhere between 30 and 90 percent of any antibiotic administered passes right through the gastrointestinal tract unchanged and is excreted into the environment, where it ravages microbial communities, often for years. To herbal expert Stephen Harrod Buhner, this is the most underappreciated threat in today’s world:

“Of all the environmental impacts of technological medicine, none have so clearly shown such frightening implications as those created by antibiotics.”7

Just like our overall health is directly correlated to the health of our gut microbiome, so do other living beings depend on beneficial microbes to protect them from threats and maintain microecological equilibrium.

“In an extremely short geologic time period Earth has been saturated with hundreds of millions of tons of nonbiodegradable, often biologically unique pharmaceuticals designed to kill bacteria. Many antibiotics (literally meaning ‘against life’) do not discriminate in their activity, but kill broad groups of diverse bacteria whenever they are used. The worldwide environmental deposition, over the past fifty years, of such huge quantities of synthetic antibiotics has initiated the most pervasive impacts on Earth’s bacterial underpinnings since oxygen-generating bacteria supplanted methanogens 2.5 billion years ago. It has, as [Stuard B.] Levy [author of the book ‘The antibiotic paradox: How the misuse of antibiotics destroys their curative powers’] comments, ‘stimulated evolutionary changes that are unparalleled in recorded biologic history.’”8

The scope of the problem is immense, and nobody really knows what this will mean for our future. Diseases of all sorts might become increasingly common, as diverse communities of beneficial microbes dwindle and are replaced by ferocious, hyper-individualist pathogens scouring an impoverished microbial moonscape.

And I haven’t even started addressing the endocrine-disrupting properties many of the aforementioned pollutants have. In the last few decades, global sperm counts have halved and female fertility has been reduced by up to 40 percent due to endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Does anyone believe that this effect is limited to humans? It can safely be assumed that the fertility rates of all but the most secluded wild animals have also started falling, because they’re exposed to the same pollutants as we are.

And this seems to be happening to the flock of chickens we keep: hatching rates have lowered steadily over the past years, despite us introducing new roosters twice to mix up the genetics. Some chicks are born so weak that they can’t walk – most of them don’t make it through the first night.9

Ultimately, both the collapse of biodiversity and climate change are aspects of a larger ecological upheaval that, together, create a positive feedback loop. Damaged ecosystems turn from carbon sink to carbon source, and increased climatic chaos makes life ever harder for the countless species whose lives are already hanging by a thread.

Partly due to the popularization of the “windscreen phenomenon” pictured above (a practical workaround for the biases caused by Shifting Baseline Syndrome by appealing to a common phenomenon that everyone remembers, and contrasting this to current reality), partly because of a growing number of concerning studies, the alarming collapse in wildlife- and particularly insect numbers slowly started gaining public attention.

Simultaneously, the climatic baseline began shifting so dramatically that more and more people feel it in their own lives. Extreme weather events have increased in frequency and intensity worldwide, and, as detailed above, the past three years (all wetter-than-average due to La Niña) resulted in erratic harvests, not only in Eastern Thailand, but seemingly all around the world.

This is more than just a stretch of bad luck, this is a trend emerging.

For the moment, things might still seem not too bad if we focus only on overall net productivity, but, as anyone embedded in a conventional farming community knows, both chemical inputs (and thus debt) and overall workload (and thus stress) have steadily increased over the past few years. Farmers now have to put in extra work to try to counteract or outbalance the effects of a collapsing biosphere and a rapidly degenerating climate: for instance, if a section of your rice field gets flooded early on in the season for more than a few days, the young rice plants drown and consequently have to be replanted. If a dryer climate and an accompanying decline in soil carbon content necessitate more irrigation, new pumps, pipes and sprinklers have to be purchased and installed, and more energy needs to be used. And if the pollinators of your main fruit crop are in decline, you will have to spend more time manually pollinating durian flowers at night.

Same overall result, but a lot more work.

The bigger picture that emerges here is sobering: certain sectors of industrial agriculture are already in decline (and have been for some time), although potential losses can still be smoothed out by intensification10 – applying more fertilizers and pesticides – for the moment.

To put it bluntly: it looks a lot like we have reached the point of diminishing returns when it comes to food cultivation.

Diminishing returns played a crucial part in the decline and collapse of most major civilizations. Joseph Tainter, in his magnum opus ‘The Collapse of Complex Societies,’ used the Roman Empire as one example of how diminishing returns develop and what they mean for a society. A strategy that is initially highly successful (such as conquering new lands in the case of the Romans) becomes the sole focus of a given society, blinding it to other strategies that might prove more successful as time passes and conditions change. In the beginning, conquering new lands was a very successful strategy, but at a certain point, the entirety of the Empire’s territory stretched so far that resources, in turn, were stretched thin, and the vast Empire became increasingly difficult to maintain – the law of diminishing returns starts kicking in. As soon as the low-hanging fruits have been picked, returns on investment become increasingly marginal, and decline is set in motion – which, when accelerated sufficiently, becomes full-blown collapse.

What territorial expansion was for the Roman Empire is extracting and burning energy (most importantly fossil fuels) to contemporary global civilization: the single thing this civilization bases its entire success and focuses all its efforts on. Our entire economy is based on the continued, ever-increasing consumption of fossil fuels.

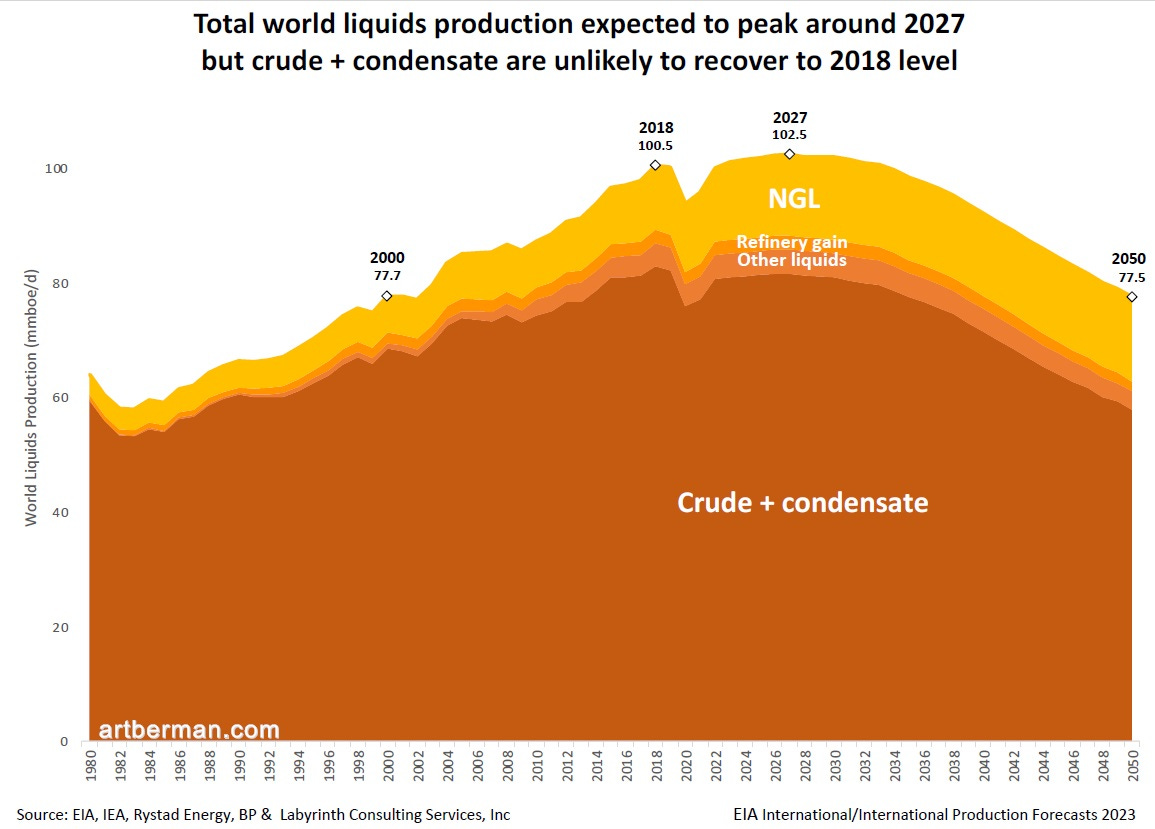

Oil is the most obvious example: The more you deplete an oil well, the more energy you need to pump it out.

We have quite likely passed the point of diminishing returns for crude oil production – which is why deep-sea drilling, shale oil and tar sands, all economically infeasible in the recent past, are now being exploited busily.

In terms of agriculture (and plant cultivation in general,) what would indicate that we’re beyond the point of diminishing returns is flat or reduced harvests, despite increasing inputs and/or working harder – exactly what many farmers are already experiencing.

But, since we’ve talked about oil as an example for diminishing returns, it’s worth briefly examining how utterly essential fossil fuels are to global industrial agriculture. In the United States, if industrial processing, transportation, storage and preparation are included into the equation, on average 10 to 14 fossil calories are burned for each food calorie consumed.

Heavy farm equipment uses plenty of fuel, as do the long supply chains that remain industry standard. Even more troubling, basically the entire world now depends on chemical fertilizers and agrochemicals, which in turn require abundant fossil fuels (as a feedstock for nitrogen fertilizer, and for the entire industrial infrastructure required to produce agricultural chemicals & machinery, as well as to process & distribute harvests). Fertilizer prices have spiked in recent years and currently remain high, exacerbating the financial pressure burdening farmers.

But the most terrifying aspect of our dilemma is this: since the so-called “Green Revolution,” the world population has grown by about five billion. What this means in the simplest terms is that five billion people are currently only alive because of an overabundance of cheap fossil fuels.11

Oil production will start its terminal decline very soon, and global agricultural yields will follow. As will population levels. If not from outright famine, then at the very least from the deterrent prospect of having to feed yet another mouth while food prices (and the cost of living in general) skyrocket.

From historic examples (Cuba’s forced transition to organic agriculture after the collapse of the Soviet Union, for instance) and personal experience, in our climate zone (the tropics) it seems to take at least about five years to transition from a chemical-intensive monoculture to a diverse, multi-storied organic polyculture producing an acceptable surplus – provided that climatic conditions are relatively stable.

Time is running out fast.

Ultimately, what all this means for us personally is that we have to let go of some the expectations we had at the beginning of this project, which is a difficult and painful process. But the future is just too uncertain for us to expect being able to eat the fruit of every tree that we planted. It is entirely possible that many fruit trees will revert to irregular fruiting cycles akin to the unpredictable habit of “mast fruiting” – the simultaneous fruiting of entire plant communities at intervals longer than one year – as many wild tropical trees already do.12 It is likely that our diet will be a lot less diverse than it currently is.

Only in years resembling the stable seasonality of bygone days will we be able to get a taste of the opportunity we missed.

The current turmoil marks the end of the Era of Abundance we’ve all been so fortunate to enjoy.

One thing that worries us in particular is the realization that, despite starting in our early 20s, we might have begun a little too late with our little rewilding journey. We were born too late – or too early – to experience “the simple life” with all its traditional perks. Restoring the land is hard work, even without the biosphere around you falling apart, and especially if you’re in a hurry. But now we have to try to heal the land faster than it deteriorates due to accelerating biosphere collapse, and it’s a race we know we ultimately can’t win.

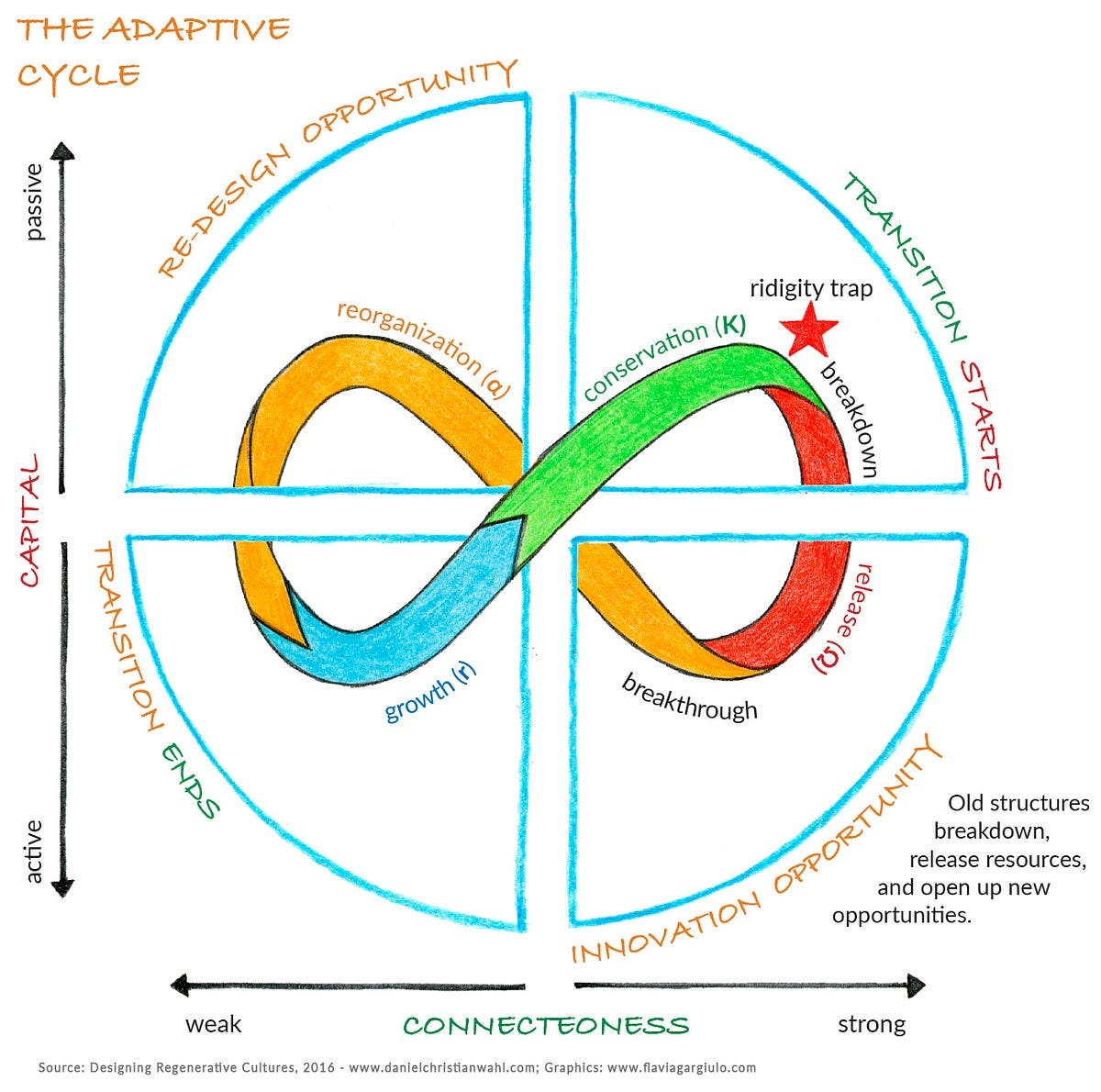

As previously stated, the global ecosystem has exited the stable state of the Holocene, and entered a phase of increasing chaotic disturbances that will eventually result in a new (albeit perhaps temporary) stable state.

That’s how systems change: after a relatively stable period, there is a (comparably) short period of violent upheaval and collapse, followed by the system slowly settling into a new stable state, and recovering from the damage.

Sooner or later, many global ecosystems are going to revert to a state somewhat similar to that of earlier epochs (before large-scale disruptions by inflated human populations), but with (initially) much higher levels of pollution and lower levels of biodiversity. For tropical areas this means that after the inevitable drop in global populations, whether through an already noticeable demographic shift – the ageing of society – or sporadic mass casualty events such as wars or famines, much of the land will revert to forest, at least where rainfall patterns haven’t been disrupted to an extent that changes the overall ecology. Some places, like parts of the inland Amazon rainforest or the Northeast of Thailand, will likely resemble the dryland savannas of Southern Africa or Northern Australia much more than tropical evergreen rainforest, because coastal deforestation has disrupted the atmospheric tree-driven conveyor belt of evapotranspiration that transports rain further inland (recycling up to 56 percent of all precipitation). Additionally, numbers of seed-dispersing animals have plummeted, and soil carbon has been all but obliterated by industrial agriculture.

If I’m allowed to be optimistic for a minute: given that some herbivore populations manage to recover after the initial human die-off, this means that whatever remnants of humanity survived the current cataclysm will probably eat more meat – new ecological niches tend to be colonized quickly, even after severe disruptions. Bullets will run out fast without global supply chains, and the remaining humans will need a bit of time to re-learn hunting, so other surviving animals have a good head start.

But we will eat a lot less fruit.

Theodore DeJong, a fruit-tree physiologist at UC Davis, was quoted by The Atlantic as saying that:

“Fruit trees evolved to live in more stable conditions; they’re exquisitely well adapted to the rhythm of a usual year. But instead of reliable seasons, they’re getting weather chaos: Springtime, already somewhat of a wild-card season, ‘is getting more and more erratic,’ […]. As a result, trees’ sense of seasonality is scrambled. And instead of reliable peaches and plums, we’re getting fruit chaos. It may not happen every year, but it’s happening more frequently.”

Most of the trees whose fruit we eat today – and, by extension, most vegetables and all staple crops – have been selectively bred and hybridized over centuries,13 and during this process the plants have lost much of their wild ancestors’ resilience and strength. There has also been a marked decrease in nutritional value, namely of phytonutrient content. We have, as one article put it, bred the nutrition out of our food.

Moreover, we have forced plants to trade strong root systems, thick skin, and compounds that fight off insects and disease for massive fruits full of sugar. Plants have become highly productive, but profoundly weak and reliant on chemicals and fertilizers. This is not to say that plant breeding per se is the culprit, but the current motivations behind it are. It is certainly possible to breed plants that are more resilient – for instance by back-crossing them with their wild ancestors14 – but we will have to lower our expectations regarding fruit- and overall harvest size, ease of processing, and probably sweetness.

Basically, we will need to reverse some of the plant breeding processes of the past few centuries – but mostly those of the past few decades, from which all the current high-yield hybrids originated – to re-create strong crop plants with thick bark, deep roots, hard shells and skins, and strong foliage.15

Or we simply eat more wild foods, which tend to be a lot more resilient.

Fruit makes up a rather small percentage of global society’s caloric intake, but they are merely the first victims of a climate in flux – the canary in the coalmine, so to speak. Important staple crops like the major grains are fast-growing, wind-pollinated annuals, and although biodiversity loss or minor changes in seasonality might not pose an immediate problem, they are highly susceptible to extreme weather. Multi-breadbasket failures are a real possibility in the coming decades that, according to a new study, have been severely underestimated as a threat. All it takes is one freak weather event.

There are already isolated instances of near-complete harvest failures in our own social circle. Last year, unseasonal rains persisting for several days soaked the entire rice crop that some families from my partner’s parents’ village had laid out to dry. Machine-harvested rice needs to be sun-dried for a few days, and rainfall (as well as consequent humidity) was high enough to cause the rice grains to germinate, cumulating in a total loss for the farmers that had harvested their crops the earliest.

As we are leaving the climatic “green zone” in which (and for which) most of our crops emerged (or were created), this means that our diets will change. This change will include, first and foremost, a reduction of certain foods (like grains, meat and fruit), an increase in diversity, and an increased seasonality. Optimally, it can encompass an increase in nutritional value (and thus health benefits) as well.

But, in the short-term, it will also lead to an overall reduction in caloric intake for all but the most privileged – which doesn’t necessarily have to be a bad thing, considering the prevalence of ‘empty calories’ in modern diets and the fact that almost 40 percent of the world’s population is obese.

A massive shift is underway that will completely reorganize the way we eat and produce food. What exactly this shift entails largely depends on the climate, but how we respond to it is up to us.

For a few years now, I have asked every farmer and gardener I had the chance to sit down with a simple question: “Do you believe that the future will be easier?”

Unsurprisingly, not a single answer has been affirmative.

The existential problems currently faced by more and more commercial fruit farms are a foretaste of what’s yet to come. As aforementioned, climate change and the collapse of the biosphere accelerate at an exponential rate, so what follows is – logically – a near-exponential decline in agricultural productivity. For an increasing number of farmers, as we have seen throughout this essay, the End of Agriculture has already arrived.

In Thailand (and seemingly most other countries), all the government can think of is handing out new loans. Proposed future “solutions” include the usual suspects: more technology, more automation, “artificial intelligence”16 – but, crucially, none of the underlying principles of food production is to be changed. As I’m always fond of pointing out, most people are stuck in the 20th century. They cling to obsolete concepts like cities, and memories of the agricultural abundance that feed them.

If we want to increase our chances of survival, we will have to think outside of the box that we’ve been trapped in ever since the climate stabilized enough for a single totalitarian subsistence mode to take over the world.

The only viable first response to the unfolding food crisis will be to radically increase the number of people working in food production. In overdeveloped countries, fewer than two percent of the population are actively engaged in food production. This number will have to go up to at least pre-industrial levels, as soon as possible.

The aforementioned demographic shift towards an older population also needs to be addressed. Few people realize how catastrophic the situation in regards to agriculture is already: the average age of farmers around the world is between 50 and 60 years.17 This means that the majority of farmers will retire in the coming two decades, and (partly due to additional resource and energy constraints) they will need to be replaced rapidly.

Especially younger people18 (including women!) have to return to the land, start restoring ecosystems, and shift as fast as possible to regenerative, ecological methods of food production. Since we cannot rely on our leaders to, well, lead us through this transition, we will somehow have to start it ourselves.

A social shift of this magnitude necessitates a shift in mentality – “farming” (or, better, food production in general) is currently seen as monotonous, backwards drudgery, dull and degrading. Yet the high overall workload of farmers from the earliest civilizations on until now results from having to feed cities and parasitic (non-producing) elites, and this will soon simply not be feasible anymore.

Another common complaint we hear from young people here in Thailand is that it is “too hot out in the sun” – which is a problem exclusive to grain monocultures. In a tree-based, multi-storied, mixed perennial polyculture (a Food Forest), it can certainly be hot, but it is usually never unbearably so. Shade is usually a byproduct of ecological farming.19 The complaint is not so much against food cultivation and farm work in general, as it is against the current methods of doing so.

In reality, gardening – if done right! – never gets boring, and almost everyone can find one way or another to make food production and ecological restoration an enjoyable and worthwhile lifestyle. The goal should be, as Daniel Zetah from New Story Farm put it in a recent interview, to “produce food as a byproduct of ecological restoration.”

Let me be honest: subsistence farming – feeding yourself from the land you inhabit – is a laborious lifestyle, at least if you’re serious about it. Restoring the soil, planting trees, and tending to the plants and animals that will feed you is hard work, especially during the first few years – but it beats any regular, nine-to-five job within the system. So far, city life might still be easier, more “comfortable” and slightly less physically demanding than farming, but this will change in the coming years.

I sometimes quip that whoever is not interested in producing food isn’t hungry enough yet.

At the same time, I am well aware of the many limitations of the response outlined above. If you expected a neat, comprehensive one-size-fits-all solution, I’m afraid I have to disappoint. There are no such solutions anymore, but there are a few promising responses: and one of them is the return to subsistence farming and a simpler life.

For the sake of brevity, I have omitted further discussion of a great many difficulties that come with this approach: where I live, household debt, land ownership and cultural rigidity20 are the predominant limiting factors. Lifestyle changes of such radical nature are thus far only possible if you happen to be in a position of relative privilege21 – at least if you want to stay within the scope of the current law.

But, as Jem Bendell has recently written, with everything unfolding at the moment, “major life changes become the least risky option.”

While it might seem counterintuitive to advise people to ‘go out there and start gardening’ after explaining at great length how the returns of said exercise will diminish over time, there is – quite frankly – little else we can do. And there is still a chance for a transition, at least for some of us, in some places.

Monocultures are an ecological novelty, unheard of in the recent geological past (with the possible exception of the immediate aftermath of natural disasters). They arose in an unusually stable climate, and they will fade away together with it. Methods of cultivation that mimic (or are nestled in) natural ecosystems, on the other hand, will have slightly better chances. So far, every year since 2020 has dealt a heavy blow for pretty much all farmers in the area we live in, and although we were hit by reduced harvests as well, we’ve managed. If a monoculture fails, you have absolutely nothing – not even money to buy food – whereas in a polyculture like ours you still have other food sources to fall back on. At the very least, you don’t starve!

It is also important to remember that none of the aforementioned means that we will see a linear decline of all yields. The end of agriculture is not the end of food. There will be occasional good years,22 just as there are periodic surprises for us: last year’s abundant crop of milkfruit, or this year’s drooping plum mango branches heavy with sweet, succulent fruit. And there are strong plants – yams, cassava, jackfruit, a few wild fruits and nuts – that defy everything the weather throws at them.

But it won’t be easy. We will struggle. We will fail, and we will try again. And again. It’s the only thing left to do.

The years of plenty are over.

This is not only true for gardening, but for life in general: the most difficult, most challenging, and most uncomfortable reality we have to face is that things are not going to be okay, at least not for a very long time.

But that doesn’t mean that we will give up – far from it. No, now we double down on our efforts. We work with religious fervor on restoring as much of the local biosphere as we can. We plant trees as if our life depended on it, because it does. We have to work harder, probably harder than we ever did in our lives, and the sooner we start, the better. There is no historic precedent, so we will have to improvise. It is going to be challenging, exhausting, humbling, but it will be wort it, even if our attempt ultimately fails.

Whether we succeed or not matters less than at least attempting collective survival.

Friedrich Nietzsche famously said:

“He who has a ‘why’ to live for can bear almost any ‘how.’”

From now on, we shall serve Life. For the first time in our lives we will find true meaning, in the monumental task to help guide the ecosystems we’re embedded in through the coming storm; a purpose so profound that it will give us all the strength this endeavor requires. We will become stewards of the land, guardians of its inhabitants.

We will realize that we are the land, and our fate is inextricably tied to it.

The Native American historian, scholar and activist Jack D. Forbes once wrote:

“I can lose my hands and still live. I can lose my legs and still live. I can lose my eyes and still live. […] But if I lose the air I die. If I lose the sun I die. If I lose the earth I die. If I lose the water I die. If I lose the plants and animals I die. All of these things are more a part of me, more essential to my every breath, than is my so-called body.”23

I write stuff like the above in my free time, when I’m not tending the piece of land we’re rewilding here at Feun Foo. As a subsistence farmer by profession I don’t have a regular income, so if you have a few bucks to spare please consider supporting my work with a small donation:

If you want to support our project on a regular basis, you can become a Patron for as little as $1 per month - cheaper than a paid subscription!

The same phenomenon is presumably responsible for the cheerful numbers reported by the Ministry of Agriculture, since all you find is overall net production – we searched in both Thai and English for average yield numbers per hectare for the main fruit crops, without success. Yields per hectare might be simultaneously overestimated (such as when applying for a new loan with the Agricultural Bank or when claiming crop damage compensation) and underestimated (to avoid taxation and higher debt repayment rates), so real numbers are hard to come by.

In a recent article in The New Yorker, climatologist Brian McNoldy was quoted as saying:

“It’s not like we’re breaking records by a little bit now and then. It’s like the whole climate just fast-forwarded by fifty or a hundred years. That’s how strange this looks.” [Emphasis added]

Insects we consider “pests,” like cockroaches and mosquitoes, seem to be much less affected by blanket applications of pesticides than beneficial ones like spiders and dragonflies - just like pathogens appear more resilient in the microbial world. This is, as David Montgomery explains in this interview with Nate Hagens, because “pathogens tend to be single organisms that do single things. The beneficial organisms tend to work in communities, and so you can think of them as a team – and a team needs different players to play different positions to provide different functionality.” Pathogens and “pests” can survive easier in radically diminished ecological communities, because they depend on nobody but their food, and maintain few (if any) symbiotic relationships.

Mature trees can yield fruit worth 20,000 Baht annually, so a farmer might spend several thousand Baht to “cure” a diseased tree with various chemicals, as I have detailed elsewhere. Although it has been known to authorities since at least 2017 that this common strain of Phytophthora has developed fungicide resistance, most farmers are not aware of this and apply fungicides in ever larger doses.

Curiously, it was a seed-grown wild durian (which tend to be a lot more resilient), but it grew in our chicken pen, where the ground is often exposed, and thus alternately waterlogged or dried out. Phytophthora seems to be one of the few fungi that thrives in those extreme conditions. All our other trees are heavily mulched at all times – against the advice of the villagers, who claim that this will attract Phytophthora – and are perfectly healthy.

Stephen Harrod Buhner, The Lost Language of Plants (2002), Chapter 6: The End of Antibiotics

Ibid.

My partner recently read the environmentalist classic ‘Silent Spring’ by Rachel Carson, and she’s alarmed by what we are witnessing here on our own little farm. Our cats had a noticeable uptick in aborted fetuses, premature births and stillbirths as well.

Another factor (as briefly mentioned in Footnote 1) is that in many parts of the world, agricultural expansion is still ongoing in one form or another. Over the past decade, old, unproductive plots have been bulldozed, burned, terraced, irrigated, sprayed, fertilized and planted in the current #1 cash crop, so that even as per-hectare durian output quite obviously declined last year, overall durian production hit an all-time high, which was of course proudly proclaimed by the various ministries and departments relating to agriculture. In a desperate bid for “good news” (like the lithium story I wrote about recently) the official reporting of numbers often reminds one of Maoist (or contemporary) China. Protect the illusion of a Glorious Future by any means necessary!

At least five billion people. Soil fertility, biodiversity and overall ecosystem health have all deteriorated immensely in the decades since, so the actual carrying capacity of the land has been reduced by the dominant culture’s land use practices.

In a concerted effort to produce more fruit than animals can eat, many tropical fruit and nut trees only produce noteworthy quantities of fruit in years with specific conditions. The last such year in our locale was 2019 – we hoped that this year might be another mast fruit year, since they seem to be triggered by drought, but so far we see no signs.

A quick sidenote to “fruitarians” or anyone claiming that “the natural diet” for humans consists mostly of fruit: the “original human diet” – if there even is such a thing! – certainly didn’t include Cavendish bananas, watermelons, oranges, mangos, or any other fruit that is the result of recent domestication and breeding. Most fruits that makes up the “fruitarian natural human diet” have been created in the last few hundred years, and consist of little else than water and sugar. If “fruitarians” knew a bit about the palatability and availability of wild fruit (and had a basic understanding of human evolution), they would surely not make such absurd claims.

Many people, like my friend Shane from Zero Input Agriculture, are already working on this.

Shane’s upcoming book “Taming the Apocalypse,” an immensely fascinating plant breeder’s manifesto for a transition to the low-tech post-Holocene era (which I had the privilege to read in advance), details methods of doing just that. Stay tuned for more info on the release!

Nate Hagens has recently said that he prefers the term “Simulated Intelligence,” and I wholeheartedly agree. There is just absolutely no way that “SI” will contribute in any meaningful fashion whatsoever to “solving” any of the countless existential problems currently afflicting agriculture. It is plagued by the same biases as its creators: the guys who thought it is smart to invest billions of dollars into vertical farming. For chrissake.

A quick online search returns the following numbers for farmers’ average age:

Thailand: 51 (2010); 53 (2018); 58.5 (2024)

Malaysia: paddy farmers >60; fruit farmers >55 (2019)

Japan: 66.2 (2010); 68.4 (2022)

United States: 57 (2017); 58.1 (2022)

Canada: 49.9 (2001); 56 (2021)

Europe: 49.2 (2004), 51.4 (2014)

I am particularly calling on my fellow millennials here. In the coming few years, a massive transfer of wealth is going to happen, as those of us lucky enough to come from relatively affluent families will inherit the accumulated wealth of the older generations – let’s use it wisely. But I’m by no means limiting my call to action to well-off millennials – all younger generations have to get their hands into the soil, and older generations have to support them in any way they can: by political activism & lobbying for this cause, by returning to traditional multi-generational households and helping with farm & restoration work, and by supplying land and financial assistance to emerging projects and willing rewilders.

I’m juggling terms here, but what I mean is the small scale-production of food from a diverse, self-sustaining ecological community, living off the surplus of the land you tend: permaculture, horticulture, subsistence farming, ecological farming, regenerative agriculture – call it what you want.

Like most East- and Southeast Asian cultures, Thailand is a “culturally tight” collectivist culture – as opposed to the hyper-individualist cultures of Western countries. Cultural expectations are high, and conforming to norms is valued highly, whereas any deviation is harshly scorned. This means that people are more likely to simply continue doing what everyone else around them does – a self-eliminating strategy in our rapidly changing world. (Please note that I am not favoring one approach over the other, but pose that the optimum probably lays somewhere in the middle, depending on the circumstances.)

‘Relative privilege’ in this context means: at the very least coming from a family that’s not in debt.

So far, the 2024 fruit season looks a lot more promising than last years’. We were spared by strong winds in cold season, and it was dry enough for most fruit crops to flower regularly. The fruit set seems good enough, but the season is far from over. Farmers are still on edge – water stress due to drought is now the main concern.

Jack D. Forbes, Columbus and Other Cannibals: The Wetiko Disease of Exploitation, Imperialism, and Terrorism (1992)

This helps me appreciate a previous piece you wrote on why climate optimists are the real threat. If you think climate change is about to be stopped with a new technology and are hell bent on ignoring bio-diversity collapse, then you will of course not be taking the need to prepare for this seriously.

Fantastic as usual David! As a "fruitarian" I was fascinated to read what you wrote about fruit trees and how dependent they are, more than most other food crops, on a reliable, consistent climate. I've noticed that in recent years in the wild extremes of fruiting (or not) of my plum trees in Oregon. Now I've just got to convince my kids to move on to land and try to become regen farmers at the same time they are working jobs to support themselves and raise their kids. Don't even know where to start on that one . . .