Seasonal Rhapsody - Part II: Wind

Tales about the Cycle(s) of Life in the Rainforest --- [Estimated reading time: 30 min.]

Life in the Jungle. A surprisingly large number of people residing in temperate climate zones are under the illusion that “the simple life” in a “tropical paradise” is pleasant, easy and worry-free – which it undoubtedly is, most of the time – but there are downsides as well. You can harvest vegetables and fruit year-round, and it is never too cold, but that doesn’t mean it’s all fun and games. In this series, I invite you to explore the stuff you won’t see on Instagram: the real story of the simple life in the tropics, a glimpse behind the scenes – without filters, raw and uncut. Biting insects, skin rashes, swarms of mosquitoes, hungry leeches, sweltering heat or torrential downpours – there is no shortage of things that try their best to make your life hell. But, please, don’t get me wrong: this kind of life is still immensely rewarding and fulfilling, full of little luxuries and surprises, and, if you ask my wife and me, it is absolutely worth it – but it’s not for everyone, and definitely not for the faint-hearted. It does take a certain toughness to weather the unique challenges our Great Mother throws at us in this climate if we live within Her limits and under Her laws, but we won’t complain – otherwise life would be too easy, which in turn would pose its own dangers: problems of a more existential manner.

Most of the problems we encounter in our daily lives are rather basic, and pretty much the same challenges our ancestors have mastered for aeons. It is the life we evolved to live over millions of years of evolution – the life we were made for.

I might have to add that while I often use the term “jungle” to describe our place, technically it’s a mix of a fruit orchard, a giant bamboo plantation and secondary forest. It will be a “real” jungle in a few decades – environmental conditions permitted. “Jungle” is an idea, a concept, not an adequate botanical description of the plant composition that makes up our habitat.

The timeless concept of the Four Elements will serve as a layout to guide us through a full year’s cycle of changing from one state to the next, each element representing one season: rainy season, cold season, early dry season, and late dry season. Water, Wind, Fire and Earth.

Due to my rather chaotic writing/gardening schedule, I write down keywords and a few paragraphs here and there almost constantly, but have to wait for the right time to formulate them into a readable text – which usually happens during rainy season (i.e. right now).

I rarely write anything about how our daily life looks like, but several readers have expressed interest in knowing more about how exactly we live. One standard I set myself for my writing is that it should be at least moderately informative, the reader should be able to take something important away from it and, in the best case, even learn something new or connect dots hitherto unpaired. When writing about our life I’m not sure I can live up to this expectation, since it is actually fairly simple. But I sincerely hope this series will at the very least be entertaining to some.

This is the second part of this series (click here to read the first part), spanning (roughly) November 2022 to January 2023.

Part Two: Wind

It is cold today, even colder than yesterday. I sit in my hammock, my “home office,” in the open space under our house, and tuck my feet deeper under my legs. I wear three layers today: a tank top, a t-shirt, and a thick hoodie, combined with a rolled-up balaclava that I wear like a hat, and a thick pair of sweatpants. It’s still cold. “I didn’t sign up for this shit,” I mutter under my breath as I reach for the hot cup of coffee next to me. Karn looks up from her book and shoots me a questioning glance, and I shake my head as I pull it deeper between my shoulders, probably looking like an annoyed, oversized turtle. The wind has picked up again, lashing relentlessly through the understory and even more viciously over the treetops. Instead of the constant concert of chirping crickets we hear during the rest of the year, right now the only sound is the howling of the wind.

The Rambutan trees behind our house, as well as two large Malay Rose Apple trees have been defoliated almost completely after last week’s stormy night. Our Cempedak tree has lost plenty of foliage as well, as did all Mangosteen trees lining the border of our land, and it will take them months to recover. All around me, strong gusts whip branches up and down and tear banana leaves to shreds.

During the two-month-long cold season, temperatures can drop down to 9°C (the lowest temperature in the last five years), which feels like some serious subzero Antarctic explorer stuff to us, although friends and family from the Global North deride us for it. On my feet I am wearing the woolen socks my grandma has knitted for us, and each time my family sends us a parcel, there’s a new pair for both of us in it. My grandma, Oma Ulla, is glad that I finally appreciate what we used to take for granted when we were children. I have to admit, as a kid I never even liked those socks much – they felt “scratchy” to our soft European feet – but now I couldn’t be gladder. They’re exactly what we need on days like this, although the irony of being glad to wear those woolen socks in a tropical country world-famous for its picturesque white beaches is not lost on me. I thank Oma Ulla on every occasion I get, and each time she promises to send more. Socks wear out fast in the tropics, as do almost all kinds of fabric. The near-constant heat and humidity slowly wear down almost any material, and I’m sure there are ten times as many species of moths that eat wool as there are back in Germany.

A shiver runs down my spine as I let my gaze sweep through the garden. The trees are rocking back and forth as if in a delirium, and the birds that usually buzz through the garden at this time have entrenched themselves in nests they’ve hastily built after the rainy season ended – they nest closer to the ground, and shield themselves from the strongest winds by nesting in crevices, behind the buttress roots of large trees, and in steep ravines. Catching insects and foraging for berries is difficult, so we assume they must get quite hungry during windy season.

The wind blows almost incessantly, and it is strong – strong enough to bend our stands of giant bamboo from one side to the other, the slender tops painting long semi-circles into the clear blue sky as they sway back and forth.

Strong winds prevail for a week at a time, sometimes longer, before taking a break for a few days. This year, the winds are exceptionally strong. When taking into account last rainy season’s exceptionally heavy downpours, it starts to look a lot like this is a first taste of the extreme weather yet to come, and the more we think about it, the more we worry. The trees have suffered enough, and if the winds get stronger over the years, who knows what this means for potential harvests.

I make a mental note to research and discuss additional potential species we can plant as wind breaks in strategic locations to protect vulnerable trees.

A few nights ago, we were barely able to get any sleep. People often use this phrase as a slight exaggeration to express that they didn’t sleep well, but we were literally not able to sleep for most of the night. The wind howled inexorably, and throughout the entire night the sound of breaking branches crashing into the bamboo thicket next to our land made it impossible for us to fall asleep. Branches of tropical trees are massive, often weighting several dozen kilos, and they crush the vegetation underneath. Since we’re situated on the northern slope of a mountainside and the wind blows southwards, the mountain we live on parts the wind, which has to go around it on both sides. This creates gusts even stronger than those that whip through the valley below, amplified by the lack of larger trees in our neighbors’ orchard (whose house is so exposed on the next hilltop that we seriously wonder why his roof doesn’t fly away).

The Durian orchard of our neighbor was defoliated almost entirely, as were the higher Durian trees on our property. The wind picked up speed considerably as it rushed through our neighbors’ neat rows of 5-year-old Durian trees, which funneled the winds and blasted them into the wall of vegetation and jungle trees on the border of our land. In previous years, this green wall has protected us from both strong wind and pesticide drift, but this year the wind was strong enough to tear holes into this defensive wall. Right behind this wall, the storm ripped the leaves off of our Mangosteen trees almost entirely on the side exposed to the wind, which in turn will severely affect the quantity we can expect to harvest later this year. No leaves, no flowers – and no flowers, no fruit.

For us this is unfortunate but not the end of the world, since we are subsistence farmers (not fruit farmers) with the most diverse orchard far and wide, by a large margin – if one crop fails, we have plenty of others, some of which might even be more productive than usual. But for the villagers, a stormy cold season like this means real trouble. If their Durian trees flower later than usual, they won’t be able to fetch a good price, and if the Mangosteen harvest fails again (as it did a few years ago for the first time in living memory, we were told) their secondary source of income is reduced drastically, and the already rapidly shrinking profit margin is further diminished.

Another benefit of our mixed orchard, which we affectionately call our “Food Jungle,” is that there are already quite a few wild forest trees that act as windbreaks for vulnerable trees. Admittedly, most of them are still too small to have any noteworthy effect, but all other farmers here have no windbreaks at all, since planting them would mean less land planted in Durian – the tree that will make them all rich (or so they think). The few forest trees that are already larger than our fruit trees definitely helped to avert the worst.

Some people here say they like the cold. As someone who has spent the better part of his life in central Europe, I have nothing but disdain for this notion. I hate the cold. Ever since I was a teenager, I have maintained the viewpoint that anything north of the Mediterranean is too hostile to qualify as prime human habitat, and I have often commented that I simply can’t comprehend how any group of paleolithic hunter-gatherers ever thought it was a good idea to venture further north, where all you gain is extra work: sewing clothes and building insulated shelters become necessities as you prepare for the cold season. Tastes differ, I guess.

Over the past decade, I’ve become even less tolerant to cold weather. For five years, I lived in the south of Thailand, where it never gets too cold for short sleeves, and where you see people wearing nothing but a sarong happily riding their motorbikes in the cool morning air, even in January. If heat is all you know, perhaps short periods of coldness are more tolerable – maybe even pleasurable. But my favorite temperature is when it’s warm enough to (theoretically) not have to wear any clothes at all, although I don’t mind sweating if it’s a few degrees above this threshold as well.

Living in a tropical country means that you don’t prepare for the cold. Houses are not insulated, and wardrobes rather light. For most of the year your main concern is to keep your home as cool as possible, allowing the air to flow freely through the house, so if there’s a month or two of colder weather, you’re at the mercy of the wind. We live in what must seem like extremely impoverished conditions (at least in Western eyes), so we don’t have the possibility to take warm showers even if we wanted to. Our “shower” is a PVC pipe with a few holes drilled into it, open to all sides, right besides our house; the greywater drains into a pile of Lady Finger Bananas and the vegetable bed behind it. Taking our daily shower takes a lot of mental preparation, and stoic discipline. The water from the rainwater tank behind our house is as cold as it gets during this season, but the real problem is the icy wind that lashes our exposed bodies – the sounds we make when we hop into the shower can probably heard throughout the valley.

I manage a grim smile when I think about the German term “Warmduscher,” someone who takes warm showers, which is employed as a not-too-serious insult for someone who’s weak and “unmanly” (by German standards). In reality, though, virtually every German I know exclusively takes warm showers, so not being a Warmduscher is marginally satisfying, a scant consolation.

While we might be reluctant to shower, the health benefits once we’ve made it into the shower are enormous, and we harden our immune systems and promote blood circulation with this daily ritual of basic hygiene mixed with Wim Hof Ice Bath Method Light.

Fortunately, Karn and I both have a “joker,” to be used when you meet two conditions: a) you haven’t done any physical work, so you didn’t sweat, and b) it is simply too damn cold to even consider undressing in the freezing wind that whips us ruthlessly.

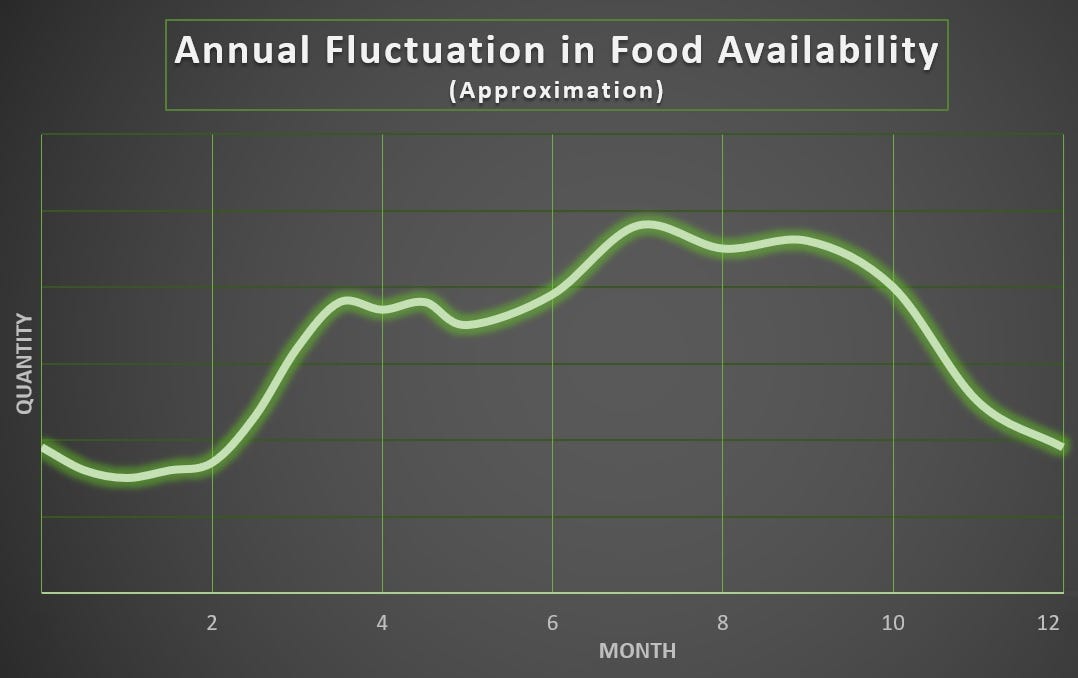

Windy season is always the time during which we harvest the least food from our garden. The entire year has ups and downs, times of plenty followed by sharp recessions in terms of availability of fruits and vegetables, but cold season is always the annual low point of productivity. The strong wind, combined with low temperatures, results in the lowest growth rate of the year. Plants prepare for the coming months without rain, and cold season is the time in which they assess their reserves, take inventory and plan for the next season. They sense the strong winds – how could you not! – and hence delay the production of new leaves and shoots, which would otherwise be instantly torn to pieces. Fortunately, there are still plenty of things we can eat (various tubers, for instance), but there is little diversity in terms of fruit and (especially) leafy greens – we usually eat the young leaves of the wild trees we utilize as jungle vegetables, and most of those plants wait until the wind abates before producing new foliage.

What made matters more serious this year was that, although the little food we harvest from the garden is usually enough for us two, we finally had volunteers (three in a row!),1 and since we had additional mouths to feed (and we wanted to provide our guests with an adequate selection of tropical fruit and regular Thai dishes as well), we had to buy so much additional food that we almost didn’t make any profit off the fee our volunteers pay us (as we write on our website, we prefer calling it a “mandatory donation” to reimburse us for our efforts). Since the cold season diet is often lacking in variety and there are few fruits in season, we had to go to the market twice a week, because otherwise we wouldn’t have dared collecting a fee for the relatively simple and repetitive meals we would have cooked. If it’s only us two, we manage, but we imagine that our guests would get tired of eating the same three dishes pretty soon.

Cold season is the best time to slaughter chickens, trap rodents and catch fish or shrimp, since even tropical animals have slightly more fat reserves during this time of the year – unfortunately, as almost always, our volunteers were vegetarians.2

The strong wind caused our two main cold season fruit crops to fail entirely this year: while we usually harvest considerable quantities of Abiu and Malay Rose Apple, the storm defoliated the trees enough for them to cease flowering instantly. Not a good start into the new year, and another clear indicator that times are changing and the weather becomes more extreme and erratic.

One category of plants we start harvesting in cold season and continue to eat throughout the entire dry season are the various tubers and starchy roots that make up an ever-growing part of our diet. Several times we dug up large purple yams with our volunteers – weighting between 4 and 6 kg each – which we cooked in coconut milk with a few bananas for a sweet, warm, soothing meal on a windy afternoon.

Soups and stews are our preferred meals during this season, since they warm you instantly and are easy to cook, requiring no complicated processing or large varieties of different ingredients. In the evenings we make a large pot of herbal tea, which we sip slowly in our hammocks after dinner. It gets dark fast around this time of the year, and we go to bed early and sleep long each night. This close to the equator, the difference between summer solstice and winter solstice is not even one hour of sunlight more or less, respectively, but we still feel the difference, especially during cold season.

On most mornings we sleep in as well, first and foremost because under our blankets it’s still warm and outside its really cold (the early morning is always the coldest time of the day), but also because the sun rises a bit later anyway – almost an hour later than in dry season – and at this time of the year she rises right behind the top of the mountain we live on, to the southeast, so that it takes until 9.30 am for the sun’s rays to start warming the treetops in our garden and the side of our house. We’re usually up by then, but confined to our cocoon of clothes and the hammocks we read and write in.

Fortunately, our first volunteer since the pandemic arrived after the worst winds had already abated and the most bitter cold had passed. It was nice to have guests again, after three years of Covid-induced reclusiveness, but we won’t go back to accepting volunteers year-round, or making it our main income source (like we did at our last project in the South). It is exhausting, and it pays very little (at least if you don’t have instagrammable lodging, hipster decorations, year-round all-you-can-eat surplus of fruit, and a few basic comforts such as WiFi, a washing machine, or unlimited electricity).

When hosting volunteers, I find myself talking for hours every day, because every question the volunteers have will sprout a dozen follow-up questions – and they have many. We usually host single volunteers, not groups (which would be too exhausting), so conversations are engaging, intense and deep. I don’t mind the talking per se, or having extensive discussions in the afternoons and evenings – which are actually rather fun for me – but having the exact same conversations over and over again makes it a strenuous exercise. I’ve been doing this for years, so I know all their arguments. I know what limitations the worldview they’re embedded in entails, I know their cultural biases, know all the things that people in the developed world have forgotten, the lies we’re told in school, and I know what aspects of our own worldview are difficult to accept, at least initially. I’ve been there, and I’ve heard it all before.

Over the years, I had time to hone my arguments and test which approaches work with different kinds of people, and without wanting to brag, I think I can be quite convincing – at least concerning the issues I deeply care about: permaculture and horticulture, indigenous land management techniques, the need to simplify, deep history, the transition from foraging to agriculture, the unfolding collapse and its numerous manifestations, and the importance of the indigenous perspective and worldview.3

Naturally, you become better at storytelling, because repetition is the best training. But repetition is also, well, repetitive – duh! – and I am now confident that I would not be a good teacher. I’m just not patient enough. You get a group of students, slowly teach them about how stuff works, and just as they start to understand the basics, they leave and you’re presented with a new set of students, and you have to start all over again. It’s tiring, at least if you do it often.

Especially for Karn it easily becomes downright boring. She, too, knows all this, and she’s heard it all before – several times over. But she cannot understand what we Westerners get out of this, endlessly discussing the minutiae of our differences in opinion, often about things so far removed from our lives that the utility of such exchange is highly dubious, always wanting to convince others to think like we do. Debating is not part of the culture here, although we both agree that it would be best to find some sort of middle way between the obsessive, multi-hour-long debates we Westerners seem to enjoy so much and the more practically oriented, less abstract, direct-experience approach of the people here.

Moreover, we would like to slowly shift our focus from Westerners to Thai people. For Westerners, visiting our garden (or similar projects) is always a nice experience and they learn a lot, but after their mandatory “gap year” they usually go back to their home country to “grow up and get a job” – which most often means becoming a cog in the machine.4 Some people choose to become smaller cogs that might even turn a little slower, or cogs that are situated in the outer layers of the machine, but, ultimately, nothing we can teach our volunteers will guarantee that they actually apply this knowledge. Once in their home country, they are too far removed from the world we immerse them in, and most people have neither land in their name, nor the courage to step out of their comfort zone for good and try something completely new (and risk alienating friends and family). The experience has changed them, but the more time they spend toiling away for the system, the more the memory fades; and while they understand the things they learned here on an intellectual level, there is simply no opportunity to apply any of this in real life, at least not in contemporary society.

If we had Thai volunteers, they could practically apply everything they’ve learned here directly, and chances that they actually have the opportunity to do so would be a lot higher.

But Thailand is rapidly developing, and there is precariously little environmental awareness, let alone collapse awareness (so far). As far as the general populace is concerned, the system still works just fine (since it’s still possible to find employment, you can buy a better mobile phone each year, and the supermarket shelves are still stocked), and problems will probably only start to become serious around the year 2100. There is a general sense to downplay climate change, and a widespread sentiment is that what’s happening is nothing out of the ordinary, since “there were exceptionally dry or wet years before.” The “Three Wise Monkeys” are an apt metaphor for how most people in Southeast Asia tend to deal with problems or uncertainties: see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil. In practice, this means that whenever there’s some concern, some looming problem, most people just ignore it and hope that it goes away on its own. Some people even believe that talking about a problem makes it worse, so by simply acknowledging that civilization is collapsing we actively hasten the downfall. I wish it was that easy.

Despite the fact that climate change is already massively impacting people around the globe – including in Thailand – people generally choose to stay ignorant, and even those that actually do know better just choose to suppress uncomfortable emotions. There is a general trend towards learned helplessness and blind obedience to authority that’s difficult to circumvent.

Regular readers of this blog will have heard the story of how our entire subdistrict used to be covered in Lychee plantations just thirty years ago, and how people razed those orchards to the ground around the turn of the millennium, because the cold season became shorter and shorter, and Lychee trees need cold weather to induce flowering. Minute changes in the climate turned highly profitable crops into useless heaps of timber, so farmers replaced them with the next big cash crop: Durian. People in the area we live in feel climate change in their lives for decades already – but if you ask them to project this trend another two or three decades into the future, you get blank stares.

We are the only ones in the village who still have Lychee trees, and this year is actually cold enough for three of them to start flowering – in a few months we’ll be able to enjoy a rare treat: locally grown, climate-change-defying Lychees!5

There are a few tasks we do every year during the windy season. More arduous tasks are removing windthrow after storms (to be used either as mulch or as firewood) and cutting bamboo for the rest of the year6 (which has the lowest starch content in cold season, so the culms keep the longest even without treatment), which we do whenever it is warm enough around noon; most other tasks are less physically demanding and can be done while sitting in our hammocks: we have to harvest and peel dry loofah to use as sponges, make cinnamon (for personal consumption, to gift to family members, and to sell to an organic restaurant in Bangkok as a side hustle), and process coffee beans that ripen around the turn of the year.

Cold season is one of two seasons where we can actually dry stuff without having to worry about mold, so for a few hours per day we hammer cinnamon wood to loosen the bark, peel coffee cherries, and use the opportunity to catch up on the latest episodes of our two favorite podcasts, The Great Simplification and Fight Like An Animal.

All the aforementioned activities are perfect for doing them as a group (and have traditionally been done in this fashion), but we still lack the community to simply do those things together with a few friends while chatting leisurely. So far, it’s only us two, so we have to compromise with modern technology, and instead of listening to the stories of our family members, friends and neighbors, we listen to strangers from other continents – as with so many technological compromises, there is both up- and downsides.7

During the day, when the temperatures rise a bit and become more tolerable, it can actually be rather nice to simply have time to do undemanding tasks while listening to inspiring and thought-stimulating conversations by like-minded folks, and consequently discuss those topics among us.

We harvested plenty of coffee beans this year – more than ten times as much as last year already – which needed to be peeled, hulled, dried and roasted. In the end we got a whole kilogram of homegrown, organic, hand-processed, medium-dark roast coffee beans. Let’s see how many months they will last us; to be self-sufficient we will need at least ten times as much, I reckon.

But we’ve reached another self-sufficiency milestone this year: for the first time we harvested enough Loofahs to last us (and our friends) the entire year. We use the inside of the dried fruit as a sponge, to wash our bodies and scrub off dead skin cells (which needs to be done daily in the tropics, otherwise the build-up of dead cells will easily make you itchy) and to do the dishes. Loofah sponges work wonders even with pretty oily dishes – they seem to absorb fats much better than regular, store-bought plastic sponges (which tend to get greasy and disgusting in no time, and regularly get torn apart and carried away by ants, presumably to be used as insulation in the nesting chambers of their burrows8). When using loofah sponges to do the dishes, we rarely ever need to use wood ashes (our most common soap replacement for doing dishes and laundry), and once they’re used up we just toss them into the vegetation around our house.

This time of the year, we sleep under three (sometimes four) blankets, because all the blankets we own are relatively thin – for half the year you barely need blankets at all! – and in addition, we might wear a shirt and shorts (which we usually don’t). Sometimes it gets so windy that we have to close the heavy wooden shutters I complained about in the first part of this series on the eastward side of the house, because the wind blows right over our faces and straight into the blankets. This year it is so cold that all three cats started crawling into our mosquito net each night: as soon as we open the zipper they dart inside, and immediately crawl under the blankets and curl up at the feet end together. Since it would be cruel to refuse them the only cozy place far and wide, we allow it.

It will be difficult to take this privilege away from them again, so I guess that’s just where our cats sleep from now on.

Due to the strong winds, one obvious upside in cold season is that there are virtually no mosquitoes. They immediately come out when the wind calms, but usually it’s simply too windy for them to fly.

But another nuisance arises soon: ticks.

There are tons of them, and we get bitten every other day, so that we have to check each other for ticks every evening before going to bed. Luckily, they don’t carry dangerous diseases as they do in temperate climates, but we’ve heard of instances where people got a strong fever from tick bites. They proliferate proficiently, and love to stay on the leaves of “Dtôn Rêo” (ต้นเร่ว; Amomum villosum), a knee- to waist-high herb in the ginger family that covers much of the ground in the upper part of the land.

Bites are very itchy, from several weeks up to several months – the spots where we’ve been bitten periodically start itching again, often in direct relation to abrupt changes in the weather, such as a rapid decrease of atmospheric pressure due to an incoming storm cell.

Tick bites are mercilessly, terribly, hair-raisingly itchy, much more than mosquito bites, and much more difficult to ignore or get used to.

When they bite the skin of your head, your hair will even fall out in the radius of a 10-Baht-coin, something you see here and there among the villagers. It will grow back after a few months, but it shows how strong their poison is.9

There is always a period of about two weeks, usually in November, when I’m alone on the farm, because Karn travels home to help with the rice harvest. Her family still harvests rice tradtionally, by hand and as a communal activity, although it felt like this year will likely have been the last. Her parents get older, and they have long been the last family in the entire region that doesn’t use the heavy combine harvesters to harvest their rice.10

Personally, I have never had the opportunity to help harvesting rice (I visited a little too late in December 2016), although the entire family invites me each year. But the freedom to just travel to other regions for a few weeks is something you give up for the different freedom of not having to slave away at a normal job. One person has to stay to feed the chickens, water the vegetable beds and the nursery, and just be there in case any elephants show up – they won’t do much damage either way, but they would know if nobody stays here and thus explore a bit more, and maybe venture closer to our house where the only two coconut palms grow that we really don’t want the elephants to eat.11

Many people who visit us, family members and friends, as well as visitors and volunteers, comment on the “severe restriction of freedom” that this poses for us. We can’t just visit relatives for a few days, since we’re bound to the land and have a commitment to our chickens, cats, and young plants, which need to be fed and watered. So far, it’s only us living here, and the neighbors are too far away (and too busy) to be bothered with doing this task for us twice a day.

But from our perspective, this is by no means an infringement on our personal freedom. It’s a neccessary responsibility, and that sort of thing should ideally fall outside of the considerations for what constitutes “freedom.” I guess it’s similar to how having a baby and raising it robs you of plenty of “freedoms,” but people generally agree that it’s worth it – it’s a trade-off. It all really depends on how you define “freedom,” and being bound to the land I inhabit doesn’t feel like my freedom is limited in any way – it is part of my freedom. I don’t have to have the ability to travel far and wide whenever I feel like it in order to feel “free.” We enjoy the freedom of not having to go anywhere else to escape dull lives of dread and drudgery. We get to experience a different kind of freedom when we simply harvest eggs from our chickens, or slaughter one on occasion. For us it’s first and foremost the other people who are forced to compromise their freedom, since they have to work boring jobs for someone else in order to make money to buy chicken eggs and meat.

I’ve long maintained that we cannot and should not try to free ourselves from evolutionarily necessary processes, and we can’t and shouldn’t escape our ecological responsibilities – the way we keep chicken is that we try to develop a symbiotic (mutually beneficial) relationship with them, which makes it our ecological responsibility to feed them. Both of those things are ultimately more important than our present personal freedom, since nobody’s freedom matters when the world becomes unsuitable for human habitation (which is currently definitely a possibility, at least in the long term). To be clear: I’m not saying that our personal freedom is not important, I just say that it’s not as important as serving the needs of the overlying superstructure that supports and nourishes you – the ecosystem you inhabit.

Ultimately, feeding the chickens and watering the young plants is never experienced as an infringement on our freedom. We get so much out of this reciprocal relationship, and watching the chickens excitedly dig into the overripe bananas, food scraps and broken rice we bring them fills our hearts with joy each and every time. It’s all a matter of perspective: if feeding the chickens is something you feel you have to do, it easily feels like compromising your freedom. But if it’s something you want to do, because it gives you joy and reaffirms the relationship as well, it is an aspect that’s entirely unrelated to perceptions of freedom. You just do it.

The time of the rice harvest is the most boring time of the year for me, since apart from sporadic short visits to friends in the valley, I only have the cats, the chickens and the spirits to talk to. During the days, I work a lot to keep myself busy, but in the evenings, when I’m usually quite tired from a hard day’s work, I watch all the movies that Karn considers “too stupid” or “a waste of time” – this year I finally had the chance to watch the new Spiderman movies (which I hated, just like every other Marvel film I’ve ever watched – for obvious reasons) and the fifth season of The Office. My inner teenager seems to demand those occasional escapades into digital consumerism – you gotta get that dopamine somehow, right? – but they help pass the time, keep me entertained, and distract me from missing Karn.

But the days after Karn returns are filled with joy, a celebration of reunion, with plenty of stories to tell from both the jungle garden and the paddy fields, punctuated by lavish feasts of all the delicious treats she brought from her home in the Northeast: fried grasshoppers, fresh fermented fish sauce, paddy crabs, wild tubers, dried meat, and “new rice” – the crop that has just been harvested and is still fragrant, sweet and soft. Especially the latter is a real delicacy, and although Westerners tend to think that “rice is rice,” it’s easily comparable to the pleasure of eating freshly baked bread.

Cold season is, as all other seasons, a different world, and although it’s definitely not my favorite season, it has its golden moments. I like the coziness of our bed, the (temporary) freedom from mosquito bites, and the heavenly scent of coffee flowers wafting through the garden that heralds the end of cold season. The air is clean and fresh, and you don’t sweat much, which is a welcome change to the general drenchedness that constitutes the norm. It is a time of introspective and intellectual endeavor, and a time to relax.

There is not much that needs to be done in the garden: the soil is still wet, the plants don’t grow much anyway, and everyone around you, both animal and plant, takes a break as well – so why shouldn’t we?

I write stuff like the above in my free time, when I’m not tending the piece of land we’re rewilding here at Feun Foo. As a subsistence farmer by profession I don’t have a regular income, so if you have a few bucks to spare please consider supporting my work with a small donation:

If you want to support our project on a regular basis, you can become a Patron for as little as $1 per month - cheaper than a paid subscription!

The first volunteer stayed with us for two weeks, the second one for a single week, and the third visitor was more of a guest generally interested in different projects, who stayed just a few nights to check out what we’re doing.

Unfortunately for them, I might add.

Many years ago, I read an interview with a member of al-Qaeda who claimed that their leader can turn everyone into a suicide bomber who listens to him for a few days. While I obviously have no intention of turning people into suicide bombers, I was genuinely impressed by the dude’s literary and charismatic skills – if you take al-Qaeda’s words at face value, at least – and I do seem to be convincing enough by now to be able to change people’s opinions about the collapse of industrial civilization and the viability and importance of the indigenous way of life in the matter of a single week. Both volunteers commented on how much they’ve learned in this short time, not only about gardening but about a whole range of other topics as well. Both appreciated the broad perspective we presented them with and called the time on our farm a “life-changing experience.” It’s feedback like this that make those efforts worthwhile for me.

This would have been my fate as well if I wouldn’t have stayed here. I regret nothing.

In the previous four years, we only harvested Lychees once – the second year after we moved here was quite cold as well, with temperatures around 10°C.

We use giant bamboo daily, for tinder, firewood, toothpicks, chopsticks, tools, furniture, poles, fencing, trellis, maintenance, and construction. Of course we usually don’t succeed in cutting enough bamboo for the entire year – usually we run out and have to harvest again around the middle of the year.

As an anarcho-primitivist, I feel compelled to point out that – as almost always with advanced technology – the downsides outweigh the benefits, especially in the long term. Humans are highly social animals.

At least that’s were we sometimes find accumulations of fine plastic grains, the size of sand grains on a beach. Ants will relentlessly attack certain soft, foamy kinds of plastic on occasion, and carry the pieces back to their homes.

So far, we’ve been relatively lucky though. Most bites were below the chest.

The rice Karn’s parents grow is of superior quality. While they use some chemical fertilizer (the dung from their cows is not enough since they share it with Karn’s sister), they don’t use any insecticides or herbicides, and rice harvested by hand contains less grass seeds. Furthermore, rice harvested with a combine harvester often needs to be sun-dried again afterwards, because the rice is harvested not when it’s completely dry but according to the schedule of the single combine harvester that has to harvest all other fields in the village as well. When Karn’s father took some of their rice to the mill to sell it, the owner of the mill said that he would personally buy the load, because it’s the most beautiful rice he’s seen all year. It’s unfortunate that they don’t get a better price for it.

The previous owner of the land planted more than fifty coconut palms over the years, but none of them survived because there is no species of palm that the elephants like better than coconut: they wait until the tree grows to a respectable size, which takes about four to five years, and then they come at night, rip the entire thing out of the ground and consume the heart of the palm within five minutes. All we want is two productive coconut palms.

Loved this post and the snapshot into your extraordinary everyday lives. I haven't left the farm for more than a day since I got my dairy goat herd many years ago. Luckily I am a natural recluse so they have been very useful at getting me out of all sorts of pointless obligations.

“But she cannot understand what we Westerners get out of this, endlessly discussing the minutiae of our differences in opinion, often about things so far removed from our lives that the utility of such exchange is highly dubious, always wanting to convince others to think like we do.”

Very well said! Here in the West, we would all do with a healthy dose of teachings from Zen about the reality of our present moment experience, as well as ‘non-belief’. We are taught from a young age as if our beliefs are ‘real’, and that we must fight and promote our own above others. When you realize that beliefs are simply, mentally speaking, a strong emotion plus a thought or two wrapped together, they become a little more silly.

When you are able to be even somewhat mindful of your experience of the present moment rather than being caught up in and distracted by these beliefs, it seems even sillier still how so many of us spend our lives in a self-inflicted mental beehive when we are born already knowing how to perfectly experience and be in the world.

Long story short, I agree with your wife a lot! And this is coming from someone who loves debate and getting caught up in having the right beliefs/mouth sounds!