Seasonal Rhapsody - Part III: Fire

Tales about the Cycle(s) of Life in the Rainforest --- [Estimated reading time: 40 min.]

Life in the Jungle. A surprisingly large number of people residing in temperate climate zones are under the illusion that “the simple life” in a “tropical paradise” is pleasant, easy and worry-free – which it undoubtedly is, most of the time – but there are downsides as well. You can harvest vegetables and fruit year-round, and it is never too cold, but that doesn’t mean it’s all fun and games. In this series, I invite you to explore the stuff you won’t see on Instagram: the real story of the simple life in the tropics, a glimpse behind the scenes – without filters, raw and uncut. Biting insects, skin rashes, swarms of mosquitoes, hungry leeches, sweltering heat or torrential downpours – there is no shortage of things that try their best to make your life hell. But, please, don’t get me wrong: this kind of life is still immensely rewarding and fulfilling, full of little luxuries and surprises, and, if you ask my wife and me, it is absolutely worth it – but it’s not for everyone, and definitely not for the faint-hearted. It does take a certain toughness to weather the unique challenges our Great Mother throws at us in this climate if we live within Her limits and under Her laws, but we won’t complain – otherwise life would be too easy, which in turn would pose its own dangers: problems of a more existential manner.

Most of the problems we encounter in our daily lives are rather basic, and pretty much the same challenges our ancestors have mastered for aeons. It is the life we evolved to live over millions of years of evolution – the life we were made for.

I might have to add that while I often use the term “jungle” to describe our place, technically it’s a mix of a fruit orchard, a giant bamboo plantation and secondary forest. It will be a “real” jungle in a few decades – environmental conditions permitted. “Jungle” is an idea, a concept, not an adequate botanical description of the plant composition that makes up our habitat.

The timeless concept of the Four Elements will serve as a layout to guide us through a full year’s cycle of changing from one state to the next, each element representing one season: rainy season, cold season, early dry season, and late dry season. Water, Wind, Fire and Earth.

Due to my rather chaotic writing/gardening schedule, I write down keywords and a few paragraphs here and there almost constantly, but have to wait for the right time to formulate them into a readable text – which usually happens during rainy season.

I rarely write anything about how our daily life looks like, but several readers have expressed interest in knowing more about how exactly we live. One standard I set myself for my writing is that it should be at least moderately informative, the reader should be able to take something important away from it and, in the best case, even learn something new or connect dots hitherto unpaired. When writing about our life I’m not sure I can live up to this expectation, since it is actually fairly simple. But I sincerely hope this series will at the very least be entertaining to some.

This is the third part of this series, set between February and April 2024, but intermixed with anecdotes and reports from the last year. I thought about keeping this series consistent within a one-year frame, but the current heatwave compels me to include the current Fire Season into this little essay series here. (Click here to read the previous part, or here to start from the beginning.)

Part Three: Fire

It is hot. Swelteringly hot. I sit in my hammock, trying hard to stay focused on the task at hand: writing. The heat quells any motivation to strain my attention, and I feel increasingly drowsy. I’ve been awake since well before 6am, so as to use the few cooler hours of the day to do some reading, while the brain is still fresh and well-rested. Now, an hour after the sun climbed above the mountains, I get a first taste of what the day has in store for us. Beads of sweat have started to run down my chest, and I wipe them away with the wet towel I have with me most of the time, either hanging around the back of my neck, swung over my shoulder or tied around my head. We call it “the poor man’s air-conditioning.”

Speaking of air: the air quality is bad again today, bad enough that we can’t see the mountain range on the other side of the valley from the window of our house. The hazy sky makes the heat even more oppressive, and we are all the gladder that we made another compromise on our otherwise stubborn low-tech ideology: a small fridge, almost like a minibar, used exclusively to cool drinking water (and occasionally for our homemade banana ice cream1). We have the extra battery capacity anyway, especially in dry season, so it’s not a terribly large transgression of our self-set limits on needless tech. We justify it to ourselves by saying that we don’t know anyone who doesn’t own a fridge, and with a bit of care it should hold a few years. At night we turn it off, to save energy (and because I’m quite strict about eliminating any artificial noises when I sleep.) Sometimes we joke that the fridge is the one who’s working the hardest right now.

We will probably not do too much today, because we try to avoid strenuous work when the air is this filthy. There is so much particulate pollution in the air that we clearly feel how we get tired faster than usual, and walking up to our chicken pen is enough to get out of breath (and break a sweat). The government currently advises all citizens – without any apparent irony – to “avoid any outdoor activities, stay inside and use an air purifier” (around 3,000 Baht on Lazada – enough to last us for a month). I’ve seen bad air before during the 2015 Southeast Asian haze, when large swathes of jungle, mostly in Indonesia, were being cleared and burned to make room for even more palm oil plantations. At the time, I was still living in the South, on a tiny island of diversity surrounded by a dark green ocean of oil palm monocultures in all directions, while the relentless forwards march of the oil palm industry thousands of kilometers away directly affected my health and well-being. Talk about interconnectedness!

But this year is worse than that. Far worse. Not as bad as last year, to be fair – when we had the worst air pollution levels on record for our province – but bad enough. Last year, we couldn’t see the mountains for months, so thick was the haze blanketing the entire region. This year we were blessed with changing winds on some occasions, so our air could clear up a bit. But up North, the city of Chiang Mai tops the list of the world’s most polluted cities almost constantly, just like last year. A friend who lives in the northernmost province says it feels like being in a cabin with the woodstove door open, as farmers in the entire valley burn their fields.

What started as a relatively promising year has quickly turned into a dystopian, sun-scorched glimpse of summers yet to come. All months this year have been above the (admittedly rather arbitrary) 1.5°C threshold – and it damn sure felt like it. I started out writing this series as a glimpse into our daily life, but it has become clear that I’m also documenting the rapid deterioration of the climate and the environment at large, which has started to surprise us anew each consecutive season. As with 2022’s exceptionally wet rainy season, and 2023’s extremely windy cold season (and basically non-existent dry season – more on that later), the 2024 hot season has shown once again that weather extremes get amplified and once-reliable patterns quickly deteriorate when direct human impact on the landscape is factored into the equation.

As soon as the cold season is over, what’s colloquially known as “fire season” or “smoke season” starts immediately. It is considerably hotter now, and I don’t even bother wearing a shirt anymore most of the time. In the mornings and evenings, all I wear on most days is a sarong, a tube-shaped piece of checkered cloth, the traditional Southeast Asian legwear for both men and women.2 There is not a single piece of clothing in the world that’s as comfortable, and I bemoan the fact that – apart from a few old people – nobody wears them anymore.

Fortunately, there are very few mosquitoes right now, so there is no need to cover your body for any purpose other than protecting it from the scorching sun. This is a welcome change from all other seasons, and reason enough for us to love dry season.

At night, it is warm enough that we sleep without even needing a blanket, and only on few days does the temperature drop enough in the early morning hours for us to draw part of the thin sheet over our legs short before dawn. For over five years, we have lived without any artificial air-conditioning – not even a fan! – and even in a post-1.5°C world, it seems we’re pretty much safe. It’s amazing how much difference it makes to live in an emerging Food Jungle, with large trees all over the land, right up to our house.

The trees have grown well over the last five years; many of those planted in the first year are already much higher than me, and there are now far more shaded places than spots with direct sunlight reaching the ground. This certainly helps keeping our garden cooler than the surrounding orchards, and probably has a slight positive effect on air quality as well. Heat records have been shattered throughout the region in the previous weeks, but I have to say that here, in our garden, it is not that bad. Situated as we are on a mountainside, there is an almost steady, gentle breeze that periodically becomes strong enough to alleviate the relentless heat and make life more bearable for us, at least for a few moments.

People who visit us often comment on how “cool” it is in our garden – rare moments of appreciation for what we do by the locals. While temperatures in the valley have consistently climbed above 40°C this year, right under our house it’s a (relatively) “comfy” 34 degrees, even during the hottest time of the day. Additionally, the humidity is really high as well, which makes all the difference. 34 degrees dry heat is fine, an average German summer. But here in the tropics, 34 degrees of muggy heat makes you want to lay down and vegetate.

Right now, we allow ourselves to be lazy, but more for health reasons than because of a lack of work: there is plenty to do, work that has piled up since last year. As the avid reader of this blog surely remembers, the previous years’ merciless, La-Niña-induced downpours basically meant that we barely had anything worthy of being called a dry season – for two years in a row! This meant that we had only very little opportunity to re-dig our vegetable beds, which we usually do every year during the time when the soil is driest (and thus easiest to mix with all sorts of soil amendments).

Sometimes visitors are surprised that we rip open the soil year after year, having heard that the least disturbance is the most preferable option (which it undoubtedly is – once the right conditions have been created). Admittedly, compared to the overall size of our garden, the area which we dig up is miniscule, about two dozen small vegetable beds (2 - 8 m2) scattered among the fruit trees around the house.

In my opinion, the most useless regenerative agriculture/permaculture technique for our particular piece of land is no-till. It might work perfectly fine if you have a thick layer of deep, dark, healthy soil with a high carbon content and lavish levels of biodiversity. But not when all your topsoil was washed down decades before you were born, when the people here first cleared the jungle, set it ablaze and consequently tilled the soil to plant rice for a few seasons. We are left with less-than-optimal soil for a fruit orchard, and terrible soil for vegetables. The redish-brown laterite soil turns into a soggy, heavy mass with the texture of pottery clay during rainy season, and bakes into an adobe-brick-like substrate in the heat of fire season. Moreover, our soil type is pretty acidic, and there is probably some sort of micronutrient deficiency – my friend Shane from Zero Input Agriculture suspects that this might be due to artificial phosphorus fertilizers that bind certain micronutrients, making them unavailable for plants. Over two decades after artificial fertilization stopped on our land, whatever nutrients weren’t leached out of the soil still remain locked up for the most part.

So we start anew, adding compost, biochar, cow, chicken and rabbit manure, crushed seashells, chopped-up leaves, ashes and rock dust, hoping that soon the fungal and microbial diversity crosses the threshold at which those molecules finally become available again and are fed back into the soil food web.

Finished vegetable beds are planted immediately, mulched heavily, and watered generously. For the first year since we moved here, we now finally feel like we have adequate mulching materials3 at hand: Napier and Vetiver grass, Leucaena and Acacia leaves, and a steady flow of banana leaf hay from the rabbit cage.

One of the main tasks in fire season is watering. We water all our vegetable beds every two days, between two to six watering cans each, depending on the size of the bed. The quality of our soil necessitates this rather frequent ritual, since it is still far away from good garden soil due to the history of land use outlined above. We fill large watering cans at one of the four faucets in our vegetable-growing area, Zone 1 & 2, around our house, and walk back and forth for an hour or more, making sure to water not only the vegetables, but also other plants close by that look particularly thirsty on any given day (like our young papaya trees).

Watering becomes somewhat monotonous after a while, but never unbearably so. While others might pity us for having to spend endless hours carrying water to the vegetable beds scattered among the fruit trees and banana plants, we chose to not look at it as something that we have to do, but something that we want to do (as I explained in the previous installment, Wind); something that is in our own best interest – if we want to eat fresh, delicious, organic produce from our own garden, without having to spend any more money on buying additional food. Of course, you could get the handful of vegetables we work hours to obtain cheaply & conveniently at the market, but the taste wouldn’t be the same, and neither would be the nutrient content.

Sometimes our friends comment gleefully on the labor it requires for us to grow a single, tiny pumpkin, which would cost 20 Baht (0.50 USD) at the local market. We retort that we don’t work for this single pumpkin plant, but for the soil in which it happens to grow, which will increase in quality from year to year, reducing the overall workload until only the planting of seeds will be required, along with a bit of chop’n’drop and a can of water here and there.

(If this plan works, that is.)

But this year we’ve finally crossed the “magic 5-year threshold,”4 and it sure seems like the hard work is starting to pay off. Despite the drought, this year has been the most productive in terms of our overall vegetable harvest so far.

A staggering variety of vegetables grows best during fire season: during no other season do we harvest this many different kinds of “normal” vegetables – stuff you would expect find at the market, as opposed to the wild or semi-domesticated “jungle vegetables” and leafy greens that we harvest and eat year-round. This year we had okra (!), cherry tomatoes, Chaya spinach, yard-long beans, and “sweet” (i.e. less spicy) peppers, and we even managed to coax a handful of pumpkins out of our slowly recovering soil.

But all those plants desperately need water.

Watering is almost like a ritual for us, a way to give back, to express gratitude, show appreciation for our one-legged relatives, and to play our part in the reciprocal relationship we strive to develop with the plants that feed us. Another important benefit of watering by hand is the opportunity to literally see the plants grow. Every four days (we divide the garden into two sections, and alternate those sections between us) we get to take a good, close look at all the plants in the vegetable beds, which provides the optimal basis for deep observation – no change is left unnoticed. Whenever a bean vine starts pulling on a nearby chili branch, new flowers or fruit emerge, or a bunch of mites show up under an eggplant leaf, we witness it happen – and are able to respond – in real-time.

This quasi-ritual of carrying & distributing the life-giving water can be a great opportunity for mindfulness practice as well, a sort of walking meditation (with a more utilitarian side effect as an extra feature).5 During this time, I often consciously attempt to be fully present in the moment – to try to shut up that pesky prefrontal cortex chatter for a minute. I try to open up my heart’s mode of perception to the feelings and sensations of the plants around me, to share their near-insatiable thirst and feel their relief when I pour the cold, clear liquid into the soil in which they are anchored. I let myself consciously feel the ground under my feet, the smell of the soil, and the symphony of crickets and birdsong that surrounds me.

Alternatively, on days where I don’t feel particular mindful, watering is a great task to contemplate whatever issue happens to require it. The task itself is not too demanding of my attention, so I have ample opportunity to let my thoughts flow and see where they lead.

The atmosphere during the late afternoon, when we water our vegetables, is often really beautiful as well. It is comfortably warm now, and as the sun is slowly setting, she bathes the garden in golden-orange light, and somewhere on the other side of the house, Karn is singing old Thai country music songs while watering her section of the garden.

Now, during the height of fire season around the end of April, as Southeast Asia is baking under a “freak heatwave,” it is so hot that many vegetable plants in our garden have slowed growth and ceased fruit and seed production altogether. They are surviving, for now, but they desperately need rain – which at this point might still be weeks away.

Curiously, this seems to only affect plants that grow in the few areas exposed to full sunlight. All vegetable beds that are at least partially protected from constant sun exposure by the light shade of trees growing overhead are doing fine, indicating a need to plant more shade trees in the two main vegetable sections.

This year, we haven’t pruned any of the shade trees in the vegetable-growing areas for the entire dry season, and it seems this strategy has paid off. In anticipation of drought, intense heat and strong solar radiation, we’ve skipped one cycle of chop’n’drop, fearing that the trees would have a hard time producing new shoots due to the lack of water. Usually, we do one large round of pruning right after dry season starts, to have heavy mulch on the ground in order to keep it from drying out too fast.6 Because we’re on the northern slope of the hill, we don’t get strong sunlight for the first few months of the year, as the sun’s arch tilts towards the south. This means that there will still be enough water stored in the soil for the trees to resume growing, and since they would have produced new growth anyway, the disturbance to overall plant growth is minimized.

Right after the brief cold season, many trees start making new leaves. The new set of leaves has to be a lot tougher, since they will be exposed to much more intense sunlight, and they are often noticeably smaller as well. As I’ve written in a previous part of this series (Water), young foliage of tropical trees can be intensely colorful, ranging from pink, Bordeaux red, to hues of purple and even blue. There are many trees that – either intentionally or unintentionally – shed plenty of foliage during the cold season’s strong winds, so once the bi-annual growth spurt7 starts, the garden instantly looks reinvigorated, in some places quite flamboyant, actually, and vibrantly alive. Even decidedly deciduous trees like the majestic Tetrameles nudiflora don’t stay naked for the entire dry season, but somehow manage to make new leaves during the driest time of the year.

This opulence of young leaves means that many herbivorous insects are abundant as well, as they want their share of the young leaves that emerge once the storms of the cold season have abated. One particular bug we’re always looking forward to encounter is a Thai version of the cockchafer called แมงกีนูน (“maeng gee noon”). They eat the foliage of many of our fruit trees,8 enough to impede growth considerably if not kept in check by a diligent (and partly nocturnal) predator: us. The beetles emerge at night, so around 8pm we make one large round through the garden, with headlamps and a tool fashioned from an old plastic bottle (with the top cut off) attached to a bamboo pole. Harvesting beetles is as easy as it gets: you simply raise the plastic container until it surrounds the leaf on which a beetle sits and give the bambo pole a slap with your other hand, which sends vibrations upwards that cause the beetle to drop from the leaf. Beetles respond to any potential threat by letting go of the leaf and flying away – often all at once – so it is important not to brush other branches, or an amarda of what always reminds me of fighter drones being launched from the belly of a spaceship descends from the tree’s crown and scatters in all directions.

One hour of collecting bugs is usually enough for a meal for two persons the next day, and probably exceeds our daily protein requirements. But this year, due to the extreme conditions, we were only able to harvest bugs a total of three times, compared with about a dozen times last year.9 We were extra careful as well, as we don’t want to stress the already struggling beetle population too much – but for years as dry as the current one, we will have to rely on other protein sources to help us through the drought. And while we could have easily eaten more chicken eggs this year, we wanted to have as many baby chicks as possible to compensate for last year’s heavy losses during rainy season. For the moment, we can still fall back on eggs from the market (which are still dead cheap: 60 Baht per dozen) – a worthwhile compromise. But even though insect season disappointed this year, we are still immensely thankful for this tasty and highly nutritious treat, provided by our environment completely free of charge.

The villagers told us that nobody here eats insects anymore, as they make you “intoxicated” – presumably because of pesticide concentrations high enough to cause acute poisoning.10 The tragedy of trading a local, fully sustainable source of protein against the dependence on factory-farmed pork meat from the store is just another point on a long list of man-made problems that seem to worsen exponentially with the proliferation of Progress & Development.

Last year, regular heavy showers caused by the third consecutive year of La Niña meant that we harvested an abundance of delicious beetles, and the trees grew unabatedly for pretty much the entire year. But the prolonged deviation from the usual flow of the seasons did seem to confuse the trees, and after this year’s record-shattering drought the unthinkable happened: for the second year in a row, the durian harvest in our district is lower than the previous, this time considerably so.11 Simultaneously, the second biggest crop, mangosteen, will disappoint again as well – after an almost complete region-wide failure last year. Farmers who usually harvested fifteen baskets every day were picking less than five baskets every two or three days (!) during last year’s (not-very-)dry season, and harvests are only slightly better this year. The current drought leads to a different set of issues, mainly a sun-burnt skin that decreases the market value of the usually rich purple mangosteen.12

There are a lot of people, mostly extended family, friends and acquaintances, that are keen to receive a share of our surplus – but last year we had to disappoint. There was barely enough of our main barter/cash crops for ourselves. When telling other people (who don’t live in the area) about the complications that arise due to adverse weather conditions, the immediate reaction was often suggesting that this happens only to us because we don’t spray, water and fertilize our trees. Sometimes this was underlined with a smug “told ya!” expression on their faces, as if they had already expected that we’d run into problems soon enough with our strange, outdated way of farming, and that an old-fashioned “slap in the face” would ultimately wake us up from our utopian dream of a better world (and presumably cause us to finally imitate all other farmers around us so we can become rich as well and can give away dozens of durian for free to show how rich we are).

Imagine being the only ones far and wide who don’t massacre their land, and being told – by people with no expertise whatsoever, mind you – that you are the one that’s doing something wrong.

But the implications of the last two years’ diminished harvests are even more worrisome – for other farmers even more than for us. We weren’t left unscathed, but we don’t depend on any particular crops for the financial survival of our project. For commerical fruit farmers, life has gotten increasingly difficult throughout the 2020s, first due to supply chain issues during the pandemic, then due to escalating climate chaos. If one of our fruit crops doesn’t produce well, we simply eat something else. But for farmers who grow only one or two kinds of fruit, a failed harvest can mean financial ruin. Moreover, the past few years have shown that even with heavy applications of nitrogen salts and superphosphate, farmers can’t squeeze another decent crop out of their trees if the weather doesn’t allow for it. This also means we’re probably beyond the point of diminishing returns already.

If there ever was a textbook example for a proverbial canary in coalmine, this is it.

And, because in every part of this series I have to complain about at least one insect or other small critter, this season’s main candidate are Horseflies – their bites often go unnoticed, tend to swell substantially, and are itchy for days. Horseflies are also extremely fast and almost impossible to kill: they always attack you from behind and stay behind your head (and thus out your field of vision) even if you turn around. I bet they have a good laugh when we throw down your tools, spin around like a dog chasing his own tail and frantically wave our arms around our heads, slapping our own face repeatedly in the process, in a futile attempt to deter them.

The days in fire season are long, and we often work until after sunset, to make up for the long siesta around noon. The inside and the outside blend together, since we don’t have to dress up like Tuareg people to go out into the garden like in rainy season. We walk barefoot everywhere now, feel the ground, the grass and the leaves under our feet, and thus get free foot reflex zone massages whenever we walk – one of the many benefits of keeping things as natural as we can.13 We can recline wherever we want, lay down on the bare ground in the shadow of any tree we like, and enjoy the different sceneries that other spots in the garden provide.

On the days when our neighbors spray and the wind carries pesticide drift to our house, we can simply move camp and temporarily flee to the pavilion down at the volunteer house, or set up our hammocks elsewhere in the garden until the smell has abated.

Probably one of the best things about fire season is the period of banana abundance that follows the end of rainy season. Bananas don’t just fruit completely randomly here – they mostly make foliage, roots and shoots in rainy season, and start fruiting en masse soon after the rains stop and the sun comes out. Contrary to popular belief, tropical horticulture does not always shower you with abundance, at least not in the first decade of any permaculture project that didn’t start in ideal conditions – yields are highly dependent on seasons and other external conditions. But when all the banana bunches start turning ripe that emerged as pointy, red flowers at the onset of the dry period, we swim in bananas. On some days, we easily eat one or two hands of bananas each, and are thus less hungry for other foods.14

Calorie-wise, bananas (and fruit in general, with a few exceptions) won’t last long, and for any effort to seriously stave off hunger you have to be pretty much constantly munching on the sweet, creamy pulp. All the short sugars are burned up fast, and it is biologically impossible to gain weight or accumulate body fat – but, to be fair, in the tropics this is not an important concern anyways.

It also feels a lot more like actually being a (somewhat caricatural) primate if you grab another banana every time you pass by the house, and devour it hungrily while walking barefoot and topless through the greenery. My ideal vision of “the good life”!

This is as good a point as any to come out of the closet on my life-long sugar addiction. Yes, I’m an addict, recovering, but prone to occasional relapses.15 To be fair, I’m probably not more addicted than pretty much everybody else I know (with the exception of my mother and, curiously, my wife16) – I’m just straightforward about it and honest in the terminology I employ. In today’s society, almost everyone is a sugar addict, often since soon after birth. We generally don’t think of it as an addiction, but psychologically speaking, it really fucking is.

In the household I grew up in, refined sugar consumption was virtually zero. My parents have been very environmental- and health-conscious for their entire adult lives. We only ate organic food (from an organic farm/food delivery service that brought us a “green box” of groceries and local, seasonal produce each week), no products from factory farms (and generally much less meat than the average Germans), and on the few occasions on which we had home-made cakes or ice cream, my parents used raw honey as a sweetener.17

While an organic diet is often seen as a sign of extensive privilege, wealth and social status these days, Germany was and is home to a small but vibrant “green movement” of people championing organic food for its beneficial effects on the health of both humans and the environment we inhabit. Many of those people, like my parents, simply chose not to buy expensive cars or television sets – we never had a TV at home! – but instead spend their income (and time) on things that actually matter.

When I was a young child, my father even baked our own bread, and every Saturday we had fresh, fragrant, steaming-hot bread rolls for breakfast – made, of course, from organic, whole grain wheat. Now if that’s not a real privilege, I don’t know what is!

Despite this head start in terms of health, sugar always had its attraction for me. First in the form of fruit and honey, the only forms of sugar I was allowed – but then, as I entered kindergarten (and was thus removed from the protective care of my parents), I discovered candy.

Every time I was invited to a friend’s birthday party, I gorged myself on everything sweet I could get my hands on. My parents had warned me about the dangerous effects of sugar ever since I was a small child, and the intense stomach ache after the first sugar-fueled binge made it clear that they had a point. But the dopamine rush was too tempting.

The amount of sugar I ingested on those birthday celebrations was not at all unusual to many of my friends at the time, many of whom drank soda instead of water at home. But it produced a high that instantly got me hooked. I ate way too much candy during my entire adolescent years, and paid dearly with deteriorating dental health. I am unfortunate to have been born with hairline cracks in my teeth, so they are exceptionally prone to discoloration and cavities, no matter how much I practice oral hygiene. I’ve already lost more teeth than I care to count, and have made peace with the fact that I will probably be toothless well before the last decade of my life. If you’re not wealthy enough, having teeth is apparently a luxury that not everyone can enjoy in the capitalist system’s final stages.

In his book “The Hacking of the American Mind,”18 Robert Lustig, MD, proposes that addiction to sugar is the initial addiction for basically all of us, and the following diversification of addictions into several categories (alcohol, shopping, social media, porn, digital entertainment, gambling, hard drugs, etc.) that are so prevalent throughout modern society are simply instances of addiction transfer. Especially in the boring, meaningless and utterly unfulfilling life civilization provides for most of us, the quick hit of dopamine that sugar provides helps us make it through the day.19 We short-circuit our reward system because otherwise life would be close to unbearable. Sometimes I think that if it wasn’t for sugar and social media, the new opium of the masses (and literal opiates, of course, along with similar substances), we would have had a revolution long ago.

But there is a way out: I found that the easiest way to curb cravings for candy, chocolate, confectionery, cakes, tarts and gummy bears is to remove myself as far as possible from the source of those temptations (which means staying in our garden as much as possible, and limiting visits to the market), and simply eat fruit. The lifestyle we’re leading yields reasonable quantities of fresh, organic fruit almost year-round, and as long as we aren’t exposed to advertising or market stalls down in the valley, this form of natural rehab works wonders.

To be honest, I do crave sweets occasionally, especially around Christmas or at birthdays, when my entire family is busy spamming our family chat with pictures of the Schwarzwälder cherry cake, the Apfelstrudel or the Christmas cookies they just savored.

I usually bake a banana cake (or two) to compensate.

Eating as many bananas as we do during fire season is also the best way to ensure digestion runs smoothly. With the fruit (and thus fiber) content in our diet, we basically never have any digestive issues.

We grow about two dozen banana cultivars, and for those unfortunate enough to have only tasted supermarket Cavendish bananas, let it suffice to say that a whole new banana universe opens up when you live in the tropics. Different cultivars vary dramatically in taste and texture, especially the cultivars commonly called “plantains.”

Jon Jandai, founder of Pun Pun Organic Farm in Chiang Mai, says that “the taste of food is a gift from Life,” and this is profoundly true. There are abundant little joys and dopamine hits to be found in a low-tech subsistence life, which are spaced apart far enough and require enough effort to achieve them so that the natural balance of hormones and neurotransmitters is not disturbed.

There are times of plenty, for instance when plum mango season starts and we literally eat “plangos” until our stomach hurts. Some of my favorite childhood memories were exactly like this: each time we would visit our grandparents during the summer, we could eat as many strawberries, raspberries, cherries, plums, blackberries, currants, blueberries, and grapes as we wanted. Paradise!!

But there are also times where we have very little fruit for a week or two – which makes the following abundance all the more enjoyable.

While I’m tapping away at the keyboard of my laptop, only interrupted periodically by wiping away sweat or to let my glance wander through the garden aimlessly when I’m stuck, the heat has intensified considerably. I increasingly let myself become distracted, by a bird landing on a nearby branch or an insect scurrying over the ground. I begin struggling to catch my thoughts, which have started to wander off into the garden more and more – a vegetable bed finished yesterday still needs mulch, optimally before the full sun dries out the soil – just about time for me to put on some pants and follow them.

Work is so much fun in dry season, no matter how physically demanding, that after a successful day of gardening, when we’re exhausted and with full stomach in our hammocks after dinner, we always excitedly discuss the next day’s tasks with great anticipation.20 There is so much to do (and look forward to), and nothing beats the feeling of being tired after a good day’s work – and the feeling of accomplishment this entails.

In Thai, you can combine any adjective with the word for “good” (ดี; ‘dee’) to indicate that it’s meaning has a positive overtone. The word for “tired” (เหนื่อย; ‘nèuay’) thus becomes เหนื่อยดี – “tired, but in a good way.” More often than not, that’s exactly how we feel at the end of a day.

And anytime it gets too hot, we just jump into the pond or under the shower, which we do up to five times a day during the hottest months, especially to cool off after a bout of exceptionally demanding work such as cutting giant bamboo or making bamboo charcoal.21

The garden often looks a little sad in fire season, since many plants (most vegetables, and even larger herbs like the ubiquitous bananas) protect themselves against the scorching sun by letting their leaves hang down, limp and feeble, to reduce the surface directly exposed to sunlight. This effect is most pronounced during the hottest hours of the day, around noon, but towards the end of fire season most banana clumps let their leaves droop in this fashion. There’s simply not enough water left, even deeper in the soil, to allow for constant evapotranspiration. Much of the ground vegetation also dries up considerably, a painful reminder that our soil is still at the very beginning of a long healing process. Many ornamentals, especially some of the larger ones in the Araceae family, die back each dry season, but they will shoot up anew as soon as the rains start again.

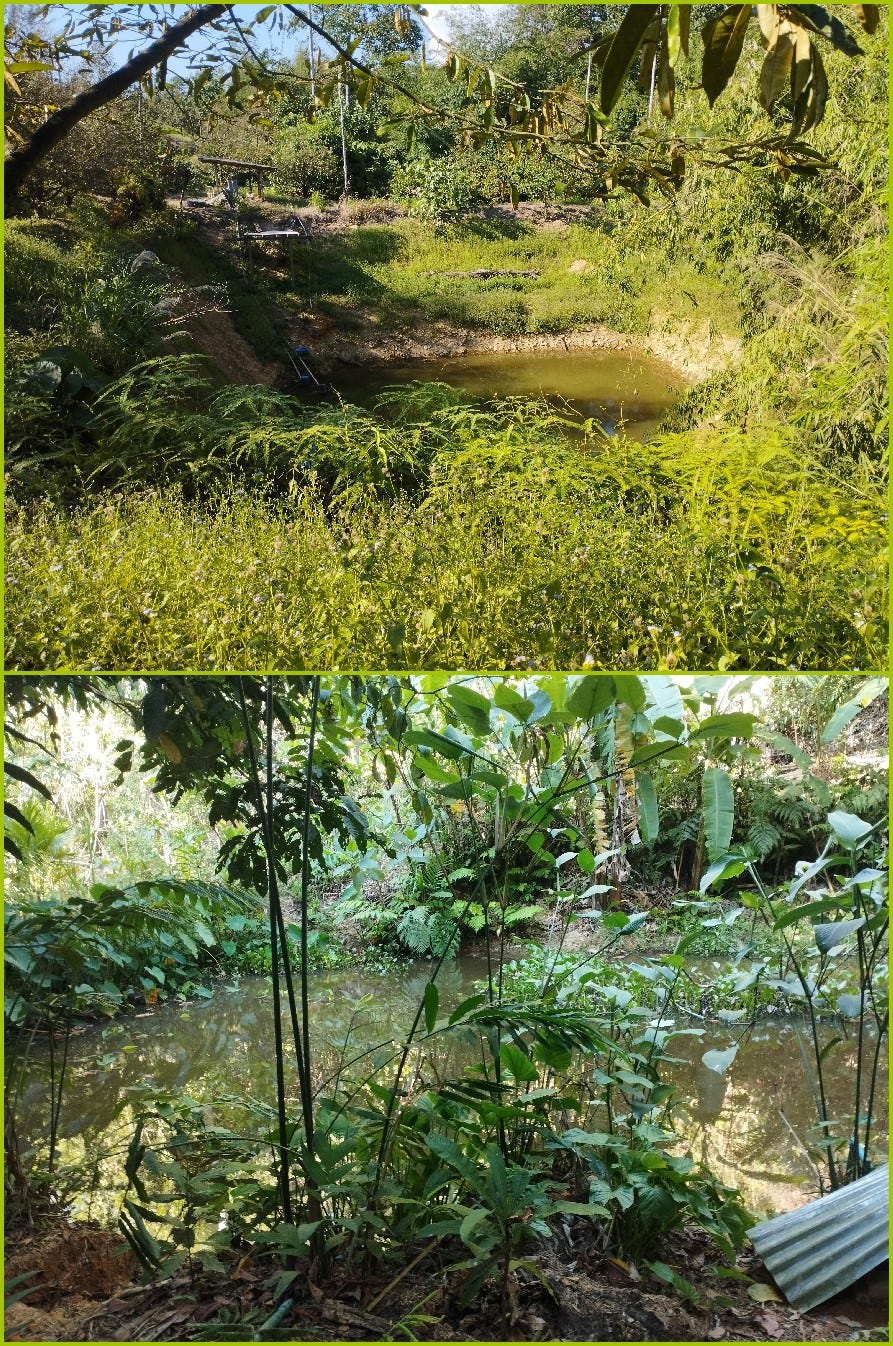

Late in fire season, when the water level in the pond has dropped a bit (and even in the darkest corners there’s no mosquitoes anymore), the most strenuous task starts: carrying mud from the pond to the fruit trees. Bill Mollison has called this technique “the Chinese peasant’s approach to permaculture,” and it certainly feels like it! Our pond is located at the lowest point of our land, at end of a steep ravine into which all runoff from the surrounding hillsides drains. This means that each year, we get a new load of fine silt, soil particles, and plenty of biomass in the form of leaves and twigs. We even harvest a few dozen buckets of sand each dry season, which practically separates itself from the lighter mud and accumulates in the corner where the inflow is. In the decade I’ve spent gardening for subsistence, the two things that surprised me most when it comes to the issue of fertilizing trees are the immense effectivity of a) “humanure” – composted human shit – and b) mud from our pond. The profound appreciation of the dark, soft muck that we scoop out of our pond with buckets is probably something only fellow gardeners can understand. “I’m rich!” I think, grinning like an idiot, every time I bring another bucket, overflowing with nutrient-dense sludge, to the surface.

When we moved here, the previous owner told us that many of the mature fruit trees produce very little to no fruit at all. Within a single year of generously applying mud around the base of those trees (always in a semi-circle along the downhill slope, to create terraces that slow down runoff over time), the results were simply astonishing.

After four years22 of toiling in this fashion for a few weeks each, the results are impressive.

And the whole thing, exhausting as it is, has a multiple benefits: the mud contains plenty of moisture as well, which slowly seeps into the ground over the course of about a week. Like this, the trees get a (temporary) relief from the horrendous thirst they’re enduring. No doubt that they are immensely thankful to us for delivering them the gift of both food and water during this time of need.

Ideally, we will excavate more mud each year than the runoff during rainy season replenishes, and the long-term goal is to be able to swim in the pond. At the deepest spot it’s now around 2 meters deep, but there’s still a few large submerged logs – practical to use as a bridge when carrying mud, but an obstacle to swimming (and diving in).

How incredibly dry everything is.

To the human eye, the soil looks bone-dry, but somehow, the trees still manage to draw their fill from it. I can’t fathom how the plants can survive this long without any rain. The soil cracks, grasses and ground vegetation partially dry up, the water level in our pond drops… And just when it looks like it couldn’t get any drier, the first dark, heavy rainclouds appear on the horizon, accompanied by the faint rumbling of thunder. For many days, they will pass overhead without pouring out their contents, and each day the anticipation rises.

It becomes more humid as well with each passing day, and just when you think it couldn’t possibly get any hotter than this, the rains finally arrive. First short and intermittent, then steady and rolling.

The end of fire season!

The relief we feel once the first heavy rain falls is hard to put into words. Of course, like in every other year, there’s plenty that’s left undone, and many projects and tasks we didn’t have time for at all.23 For instance, I initially had planned to build a primitive hut (in the style of the Baka/BaMbuti) in the upper part of the land this year, which becomes considerably less fun once the rain summons the swarms of mosquitoes that accompany us during the rest of the year. And, to be honest we would have liked the opportunity to excavate even more mud – in total we managed to get out a mere 400+ buckets, just short of our inital goal of over five hundred.

But now the rains have arrived, and a new season, different altogether, is starting.

And just like that, we have collectively survived another dry season – and not just any dry season, mind you, but the driest on record! If that’s not a reason to celebrate, I don’t know what is.

The plants are rejoicing – so why shouldn’t we?

I write stuff like the above in my free time, when I’m not tending the piece of land we’re rewilding here at Feun Foo. As a subsistence farmer by profession I don’t have a regular income, so if you have a few bucks to spare please consider supporting my work with a small donation:

If you want to support our project on a regular basis, you can become a Patron for as little as $1 per month - cheaper than a paid subscription!

Our banana ice cream (usually) has only two ingredients: mashed bananas and coconut milk. Sometimes we add cacao powder, home-made fruit jam, or other mashed fruit. I would add a picture, but, to be honest, it doesn’t look too appetizing.

The only difference is the pattern – men’s sarongs have a simple checkered pattern in two or more colors, whereas women’s have exquisite floral patterns, or colorful traditional designs varying from province to province.

An average you hear often is that, in a tropical climate, about 30 percent (!) of the land should be planted in biomass crops for mulching if you want to avoid pricy external inputs. Our land used to be a fruit orchard without any biomass crops, so we had to wait a few years until the plants we’d selected for that purpose grew large enough to allow regular pruning.

More on that threshold in the September 2024 Rewilding Update!

I don’t practice “regular” meditation, although I’ve tried it in the first few years after I moved to Thailand. I found that even regular practice provides no noteworthy benefit for me – for instance, I barely ever have trouble falling asleep at night, and I’m usually kept well entertained by the near-constant internal dialogue my mind produces – so I stopped practicing after a while. Moreover, subsistence farming as a lifestyle has plenty of opportunities to practice mindfulness. Some tasks are almost inherently meditative, such as sawing or splitting wood, weeding, carrying mud, digging, and the processing of many foodstuffs, which all are somewhat repetitive, but require enough attention to stay focused on the present moment. Additionally, I’ve found out that the closest analog I have in my daily life is climbing trees (more on that in an upcoming essay, titled “Climbing is my Meditation” – stay tuned!).

We still managed to mulch adequately, since the biomass crops we’ve planted five years ago have become massive trees in the meantime, and one 6-m-tall Acacia mangium provides enough mulch for a pretty large area. We just pruned fewer (but larger) individual trees.

The periods of most intense plant growth are the beginning of hot season and the beginning of rainy season.

Their favorite foods are (in descending order) the foliage of: ลำดวน (Melodorum fruticosum), Soursop (Annona muricata), Rollinia (Rollinia deliciosa), Atemoya (Annona × atemoya), จำปี (Magnolia × alba), Starfruit (Averrhoa carambola), and a handful of wild forest trees, indicating a strong preference for members of the Annonaceae family.

We ensure the survival of future generations by enforcing a strict taboo: we wait for at least two weeks after the emergence of the first few beetles, so that the first generation to emerge from the soil has the best chances to mate and produce the next year’s generation.

We’ve never experienced any symptoms of poisoning (or even a stomach ache), but we make sure to harvest beetles only from trees that border the Nature Reserve, not from the area that is occasionally exposed to pesticide drift. The cockchafers probably still contain some pesticides, but in today’s world there’s simply no way around that anymore – which is why we designed our own >99% Organic logo.

The latest forecasts predict a decline between 50 and 60 percent (!!) for the overall durian harvest in 2024.

Because we grow food primarily for ourselves, this is not a probelm for us at all. Quite the contrary: the mangosteen with the ugliest skin are often the sweetest.

A visiting friend recently asked us if we injure ourselves at all, since the skin on our feet must be pretty thick – to which I replied: “Oh, constantly!” The soles of our feet are constantly covered with tiny marks and cuts left by various objects of concern: sharp pieces of bamboo twigs, the spines & thorns of various palms, and the occasional shell fragment or chipped stone. Most injuries are not too deep, though, and heal within a day or two. We take great care to pile all thorny material together and keep all the footpaths “walkable barefoot” at all times, but sometimes we still overlook a rattan leaf tip, or the chicken throw some Salak palm fonds onto the path as they rustle through the ground cover.

This should by no means be taken as an attempt to become “fruitarians,” but simply a result of seasonal dietary variability, such as during durian or avocado season. I passionately loathe fruitarians’ arguments about how the “natural” human diet allegedly consists mostly of fruit – it flies in the face of (evolutionary) biology and anthropology. Sure, fruit is some of the most immediately gratifying food there is, but you risk malnutrition and disease if you (rather childishly, I might add) decide that you’re only going to eat the sweet stuff.

Such as when my wife’s little sister comes to visit us and brings me a box of Dunkin’ Donuts.

Maybe Sigmund Freud would have something smart to say about this coincidence?

My grandfather is a beekeeper, so we basically had as much free honey as we wanted. Definitely a cheat code for our otherwise draconian no-sugar policy.

And, of course, ‘the hacking of the minds of everyone else in the world’ as well. But tell that to a Yankee.

And it works! Each time we go to the city, I cave in to my desires/addiction and buy a cup of Thai green (iced) tea with milk (lovingly nicknamed “diabetes in a bag” by my wife) at one of the countless small coffe/tea stands that dot every road in the country – always careful to add an emphatic “not sweet!!!” to the order, since otherwise the sweetness would almost be unbearable, even for me. The end result is still plenty sweet, and I can’t fathom how regular people can order their drinks “extra sweet.” The quick dopamine fix makes it a lot easier to handle the profound sensory overload we experience each time we venture to more densely populated places, and if I don’t have my gree tea the stress makes me grumpy and easily upset. No wonder people down there drink that stuff almost constantly.

My brother recently asked me if there is any task that I don’t enjoy, and – to my own surprise, I might add – I couldn’t think of a single thing!

Last time we made charcoal, the heat I was exposed to while stoking the fire with a long pole was intense enough to deform the flattened piece of PVC pipe I use as a makeshift sheath for my machete. I usually wear a cloth soaked in cold water around my head, and I’m confindent that no other task brings me so close to a heatstroke.

Last year, the reoccuring rains during the dry season didn’t allow us to continue the practice, since it’s far, far easier when there’s no mosquitoes around. If only your head sticks out of the water and both hands are busy holding a heavy bucket, you’re easy prey for swarms of hungry blood-suckers.

Paradoxically, our to-do list gets longer the more we get done, as each season more and more opportunities for further improvement, diversification and beautification arise.

Have you tried a yoke to carry water or mud? It helps me a lot but my yoke is quite long so your narrow paths might be a problem. My buckets are bigger so carrying with hands, they are in the way of my legs. With a yoke they dont, and i dont have to grip with my hands. The deep tissue shoulder massage is excellent too. Long ago the veggie farmers here have special watering cans on a yoke and they can water on both sides while walking.

My ponds have giant leeches but less mozzies. They are grown full of grass and i have been weeding them.

Very well written. Barring massive nuclear weapon events, you and those few with the skills you have developed will be amongst the survivors of the coming contraction of plague phase. (quadrupling in the lifespan of some living members) As I prefer much cooler weather, and I'm nearly 79, If I were half my age I'd choose a sparsely populated area with plenty of forests for firewood and reasonably rich soils. I also would eat fish and small game if plentiful. Meanwhile, I admire your fortitude. Cheers on the Downslope of Western Civilization and the biosphere as human habitat.