The People of the Rattan Vine Mountain, I.

An immersive ethnography (Cli-Fi) - Chapter One: Unbidden Guests --- [Estimated reading time: 1h]

I never thought I would ever write fiction. Ever. I’m not a native speaker, and I always thought it would be somewhat pretentious if I even tried. And maybe it is.

But I tried nonetheless, and I am satisfied enough with the first results to just throw ‘em out there and see what happens. What changed my mind was, first and foremost, the urge to write something more positive than the usual topics of this blog. In one of my essays, for instance, I added a disclaimer at the beginning, warning people who suffer from eco-anxiety about triggering content. I wanted to add a sentence about how those people should go and read one of my more uplifting essays instead, but I was shocked to realize that I don’t write uplifting articles (apart from Following the Call of a Plant, maybe, or Back to the Land, or – if there ever was anything uplifting about death – Where we go when we die). This blog is called An Animist’s Ramblings for a reason. It’s what I’m good at, and what I enjoy (due to some twisted neural misexpression that probably has to do with my upbringing in Germany, the world capital of complaints and humorouslessness. I mean humorousnessless. Ah, forget it!).

Ever since, for well over a year now, this lack of “uplift” in my blog has really started bothering me, and I thought a lot about how to change that. In turbulent times like these, what we need most is a positive vision, something to look forward to and work towards, not yet another article explaining how fucked up everything is, I thought, and thus started to think more about how I want the world to be like – and use this as a blueprint for my writing. The following is the result of this attempt.

If it is not immediately apparent in which way this story could be considered uplifting, please bear with me. Considering the utter devastation we will witness in the coming decades, it is already remarkable enough that the community described herein has managed to cope with the collapse of global civilization and the breakdown of global weather patterns, and has been able to create a sustainable, fulfilling, wholesome and meaningful way of life, in close alignment with human Nature and the lifestyle we evolved to live.

Writing a (short) story is completely new for me, and just an experiment – for now. As I said, I’ve never written fiction before, and I’m not sure if I’m any good at it (but if the feedback turns out to be positive, I will write more!).

But, please, always remember that this is fiction – not a prophecy! It’s one idea of how things might turn out, but it’s definitely not to be taken too seriously.

Another consideration is that, as the two-year anniversary of this blog nears, I would like to try to nudge a few of you, my dear readers (particularly those of you well enough off to have a few bucks left at the end of each month), to upgrade your free subscription to a paid one. We depend (at least partially) on the income from my writing to keep our young rewilding project running, and since everything is getting more expensive, we find that our usual basis of donations has less and less real-world value when exchanged for goods and services. We are not hunter-gatherers (yet), nor are we fully self-sufficient (if that’s even ever a real possibility), and thus need at least some money to keep going.

Alternatively, I will gift a paid subscription to everyone supporting us on Patreon (starting at 1 USD/month – cheaper than a paid subscription!).

My regular essays will still be freely available, but – following the example of Arnold Schroder from Fight Like An Animal with his “FLAA 2050” podcasts from the future and Shane Simonsen from Zero Input Agriculture with his series of bio-sci-fi novellas – I will probably paywall my fiction (after this initial free first chapter - and maybe even after the second one, if this strategy doesn’t work).

[Edit: the second chapter is available for free now!]

To be completely honest, if you really want to read it, you can still opt for a free 7-day trial, and I won’t be mad – I simply want to show that writing has become more than just a hobby for me, and I am serious enough about it to ask people to pay for some of the content (at least if they have enough money). Times are hard (and getting harder by the day), and we definitely feel the pinch of a contracting economy and a civilization in decline.

But now that the formalities are dealt with, and without further ado:

CHAPTER ONE: Unbidden guests

There was tension in the air. It had started a few minutes ago, first a low hum, like the massive carpenter bees that live in dry bamboo segments, then swelling slowly into what Hector – to his own surprise – could only identify as the unmistakable rapid pulse of the rotor blades of a helicopter.

Could it be? But how?

Ever since the Fall, he hadn’t seen – or heard – a helicopter. Nor had anyone else he had met. It seemed strange, threatening, like an assault on the usual order: a violent intrusion into the symphony of birds, monkeys, squirrels, cicadas, frogs and crickets that usually droned through this endless ocean of green at that time of the day.

It must have been, what, almost twenty years now? Hector thoughtfully tilted his head, squinted into the sun and scratched his beard.

Without calendars and the ubiquitous smartphones everyone used to carry around with them, it had become hard to keep track of time – especially if you lived in the tropics, where every day was approximately twelve hours long, and especially since the seasons were not annual phenomena anymore, as they used to be, but a never-ending assault of water – horizontal, vertical, rising from the ground and soaking you from head to toe – for what must be a whole year or two, followed by scorching sun, cracked soil, and meager meals for an equal amount of time. To be honest, it was hard to know for sure how long. Nobody kept track of the days, and even long before the Fall Hector was already constantly confused by which day of the week it is – Monday again? – because, as he philosophized, if you live a simple life in tune with the seasons and the land, days merge into each other seamlessly, and you easily lose track of time. Civilization had insisted that time progresses along a linear axis, but if you lived like him, it was no mystery as to why time was perceived to be circular by all indigenous societies. Time may seem to march forward relentlessly, but every circle looks like a straight line if you zoom in close enough. Nonetheless, despite its myopia – or maybe because of it – the serpent had bitten its own tail: Civilization itself had fallen victim to its lies, and its insistence on an indefinite right to exist – a loophole to exit the never-ending cycle of growth and decay – had become its demise.

You can’t mess with the laws of the Universe. Or, how Civilization would have put it, the laws of ‘physics.’ What goes up must come down. Gravity, you know?

Truth be told, talking about “the Fall” was a bit sensationalist, even for Hector’s standards. Everyone knew this, yet people already talked of it as if it was some mystical event in Deep Time, which it of course would become in due time, Hector made sure of that. It was much less of a singular Fall, he knew that, but more like a series of escalating mishaps ending in utter catastrophe – imagine a drunk staggering down a staircase – but, as he always had insisted, “the Fall” makes for a better story for the kids. A better Myth for future generations.

If Hector would have had to pin it down to a single event, it would have been the point at which the already erratic fuel supply abruptly came to a halt – and with it the supply lines for the big cities. The electricity grid collapsed within days afterwards, and only sporadically came back online for a few hours per day afterwards, without any obvious schedule, before completely ceasing function a few weeks after. Electricity had been fairly intermittent long before – at least for commoners – but the near-instantaneous loss of fossil fuels that still accounted for the bulk of power generation probably delivered the final blow.

Nobody ever knew what exactly caused it, but for a culture that needed gasoline like an animal needs blood, the sudden cessation of its flow was lethal. Life in the cities was hell even long before that, no doubt, with shortages of everything from medicine to clean water being the norm for those unfortunate enough to live outside the heavily protected gated communities that had sprung up everywhere in the years leading up to the Fall – but after the gasoline stopped coming in, things deteriorated quickly. Hector had only heard the stories that the refugees sometimes told hesitantly, mostly when they were drunk and it was late enough that everyone else had gone to bed, but it must have been a nightmare.

They talked about “the Fall,” singular, to make it easier to comprehend, and to create a cautionary tale ending in the ultimate calamity, a disaster that people wouldn’t forget for centuries, and maybe – hopefully, Hector thought – for much longer. His explanation made sense: The future of their people, probably of the entire human race, depended on them learning their lesson from the Age of Separation, the millennia that most of humanity had lived as if there was no tomorrow, as if they had neither ancestors nor descendants, as if they were not a part of this planet and somehow could get away with it. It is crucial that this lesson survives for as long as possible, Hector often said, because the future depends on it.

Kids were, quite literally, the future, so they had to make sure the children really got it, and didn’t repeat the same mistakes, or fall for the same empty promises of god-like power over all others – whether the one-, two-, four- or the many-legged. But people planned their families carefully these days. There were not many kids around anymore, so Hector and his wife Yaem were all the happier every time someone much younger than them visited their house. Seeing kids gave them hope, but made them sad at the same time. They had thought about having kids when they were much younger, in a time that seemed like an eternity ago. In hindsight, and from a rational perspective, they were both glad they didn’t, though. The first few years before – and especially after – the Fall were much easier without kids.

At the beginning of the millennium, nobody had expected the weather to change that fast. Even scientists who had devoted their life to studying the climate were shell-shocked by how fast things degenerated. For Hector, this merely meant that they didn’t understand – or couldn’t envision – exponentiality outside of their abstract models and theories, applied to real life, in real time. But they were surprised as well, Yaem and him, caught off guard, and it nearly cost them their lives. Thinking you can feed yourself and actually doing so in a situation that’s already overladen with stressors of all sorts are two very different things. They were lucky, though, because at least they started preparing in time. They had seen the early warning signs, watched the proverbial canary in the coalmine slowly suffocate under the heat domes that crossed the land every few months, saw the insect population decline from year to year, and witnessed the complete derailment of weather patterns and annual seasonal changes that were relatively predictable for millennia. They had tried to talk to their neighbors, to the Chief of the Village, but nobody would listen. People simply switched subjects when they tried to steer the conversation towards the looming polycrisis, the multiple bubbles just waiting to burst. Their preparations were not sufficient, sure, but it was better than not being prepared at all, like most people at that time were.

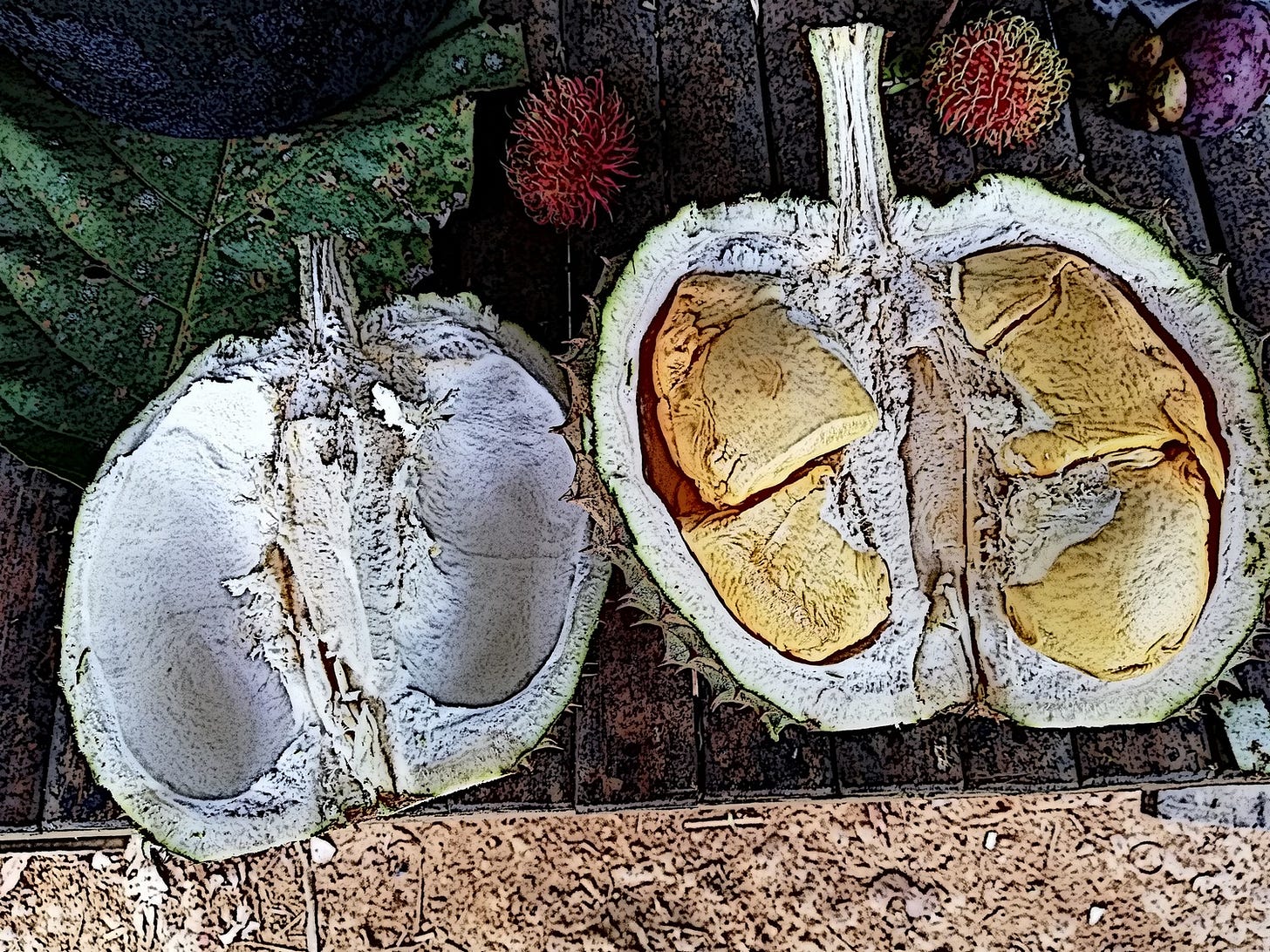

What had surprised both of them was their little grove of milk trees from South America. They had proven to be even stronger and more resilient to averse climatic conditions than they could have ever hoped for. They fruited reliably every few months, the starchy seeds were much sought after in the entire area, and the bark could be tapped seasonally to provide a protein-rich, creamy-white latex which could be diluted with water and drunk like milk – It even tastes somewhat like milk, Yaem often remarked, although they could barely remember how cow milk tasted like. It was the milk trees – and the ubiquitous cluster jackfruits, of course – that had saved their lives, and that of the others down in the village, plus those of the first few refugees that had arrived before the first raincycle started. They were lucky, really fucking lucky, as Hector always said, and they knew that. It could have easily been them whose garden was consumed by the flames of the massive forest fires two cycles earlier, or buried by the landslide that went off on the other side of the hill towards the end of the last raincycle.

That’s how they divided time now, in an attempt to shake off the yoke that linear time had imposed on their lives, the delusions of one life and one life only, followed by eternal nothingness. ‘The scientific worldview,’ they had called it. What used to be ‘year this’ and ‘year that’ were now ‘raincycles’ or ‘suncycles,’ depending on the prevailing weather. There were still occasional heavy downpours during the suncycles, usually accompanied by almost unbearable humidity, just as there were sunny days during raincycles – but it was the exception, not the norm.

Nobody was counting anymore, but Hector guessed that it should be somewhere around 2050 CE, if his calculations were of any value, and, judging from the waxy baldness spreading over the top of his head, he thought that he might be nearing the age of sixty. But he had given up agonizing over numbers. After all, who cares?

At least I can still climb like someone half my age, Hector always joked.

And although his eyesight had finally started caving in, he was still the most active member of the Treeclimber guild – Hector insisted that there was no feeling better than the pleasant tipsiness of standing on solid ground after having spent hours high up in a tree, when it seems as if you’re still swaying with the wind…

Who is that ‘old man’ that everyone keeps talking about, he laughed each time when someone carefully inquired if it wasn’t time to retire from the guild – a whole lifetime harvesting tree fruit, and not a single serious fall: one of his proudest achievements!

Hector and Yaem lived a bit further away from the other houses in the village, a remnant of the time before the Fall, when they had valued their privacy and solitude.

But on this day, as if predestined by the fate that the gods had in place for them, their house was full of people. They were about to plan the upcoming communal hunt and the routes, groups and other details for the subsequent suncycle migration, and a representative from every family of the village had visited – some brought their children or grandchildren as well. The deafening roar of the helicopter and the clouds of leaves and dust it kicked up clearly upset those plans.

The elders were sitting on the large, low table under their house, and a few other people had huddled around it to examine the makeshift map from leaves, twigs, stones and pieces of bamboo Hector had arranged, each symbolizing certain trees, trails, creeks or mountains. Everyone was on their feet now.

“Is that a… helicopter?” a young girl named Sung asked fearfully, clutching her mother’s leg. She drew out the last syllable in typical Thai fashion – he-li-cop-TUUR – like every other anglicism that had found its way into their language. She had never seen one, let alone heard one, but she had run towards the treeline when the noise was still tolerable, and came sprinting back once the machine rose over the hills and the noise intensified. She must have heard descriptions of helicopters from her uncle, who had served in the Thai military for several years, before defecting once the troops were deployed to quell unrest in the cities.

“Yes, but don’t worry,” Hector told her, giving her mother a reassuring nod, “we’ve planned for this!”

Well, truth was, they hadn’t – at least not for this exact scenario – but it’s not like they lived on the moon. They had protocols for encounters with potential hostiles. Ever since the Fall, they had feared that the day might come that they would have to take up arms to defend themselves – so far they had been able to avoid large-scale conflicts, and everyone knew how lucky they were for it. It was Hector’s conviction that violence was an inevitable part of Nature, of Life, but it should be minimized wherever possible. Let’s just hope that today’s not the day, he thought as he stepped out from under their wood-paneled stilt house to get a glimpse of the approaching machine.

The throbbing of the rotor blades woke the entire village below from their midday slumber, and in an instant there were children darting in and out of the tree cover to steal a quick glance at the massive machine hovering above the canopy. Forming a circle right below the helicopter, the tree crowns violently swayed back and forth, as if forced to partake in some strange ritual trance. A frightening sight, even for the handful of elders who had seen helicopters before. Hector instinctively reached for his bow and a handful of arrows, and motioned the small group that had been sitting under their house to follow his lead. Everyone grabbed whatever improvised weapon they could take hold of – machetes, the wooden clubs for mashing cassava, rods made from rattan, the ironwood spears they used for hunting – and ran out to the only place in a radius of at least several dozen kilometers where a helicopter could land: the clearing where they usually held ceremonies and played games, a bit downhill from Yaem’s piece of forest on the northwestern slope of Rattan Vine Mountain. A handful of members from the Council of Elders went forward to receive the unbidden guests, covering their faces with their scarfs to protect themselves from the dust plumes the wind kicked up into their faces.

Hector stood well behind the crowd, slightly further uphill in the shadow of the tree line, and hastily wrapped his own scarf around his head and face, his bow leaning against the trunk of a milk tree. Being white-skinned used to be a privilege before the Fall, although for Hector it was always a great source of shame: shame at what the people of his culture had done to the planet and all its inhabitants.

Nowadays being white-skinned could get you killed. He’d heard people cite the utter irresponsibility of Western countries that caused the climate to derail in the first place as a reason to beat up white people and rob them, or worse. Caucasians had become the scapegoats, even in the years preceding the Fall, and somehow Hector could always understand it. Hell, he passionately hated Westerners as well, which was one of the main reasons why he wound up in Southeast Asia in the first place. Escaping the World Eaters and their rules and machines, looking for a simpler life, in tune with the seasons and the rhythm of the land. He doubted that many of the Westerners who had lived in the area survived the first few months after the Fall, trapped between hungry and angry mobs of brown people, who all witnessed the response of the rich countries in the years leading up to the Fall: erecting wall after wall crowned with razor wire to deter the hordes of displaced and desperate people, the merciless struggle over the last scraps of crucial resources, the rumors about bloody exfiltration missions they conducted to secure professionals of all fields and from all around the world.

Anyway, these days it’s best you don’t parade your ethnicity around, Hector thought. His community knew and accepted him even before the Fall, despite his skin color, and they had hidden or defended him on numerous occasions.

Needless to say, he didn’t travel much.

Most of the kids were with him now, many of them seriously afraid of the intense roar the helicopter emitted. The coconut palms on the eastern side of the clearing were rocked back and forth furiously by the rotor downwash, like someone had grabbed them by the collar and shook them, palm fronds flying like long hair in the wind. The loudest noise the innocent little beings crowding around Hector had ever heard were the immense thunderstorms passing right overhead during the beginning and the end of the raincycles, but the noise of the helicopter just didn’t seem to abate, an endless assault on ones ear drums – plus, Hector remembered with a grin, he had once told them that the reason why machines roar loudly is because they were actually powered by screams of agony: the cries of the spirits of long-dead plants and animals that had been sleeping fossilized for millions of years, but were disturbed in their sleep when the World Eaters dug them up. Burning the spirits of our long-gone ancestors makes them scream in pain, that’s why motors make such noises, kids.

They had seen cars – or better, what was left of them – and the village still maintained a single motorbike with a side wagon, to help carry heavy loads, if they happened to have a bottle of biofuel at hand that the people of the plains further inland distilled from sugar cane. The motorbike was already pretty loud, an obscenity, if you asked Hector, but they couldn’t use it more often than a handful of times during the suncycles anyway, so usually it was pretty quiet – apart from the daily concert of cicadas at dusk.

By the faces of some of the youngsters he could tell that they were recalling that story now, eyes and mouths gaping, staring in utter disbelief at the otherworldly scenery unfolding in front of them, vivid images of animal and plant spirits being burned to death firing their imagination.

The helicopter slowly descended in the middle of the clearing and touched down – almost elegant, a surprisingly soft landing for such a large machine – on the red ground. “A skillful pilot,” Hector remarked, turning his head to face Jaak, a teenager from their village and the son of a refugee family, who had taken cover behind the large buttress root of a milk tree next to him and cautiously peered out from behind the trunk to observe the strange scene taking place in the center of their usually rather tranquil little community. It was an old military helicopter, a Huey, like those used in Vietnam almost a century ago, that had been kept in surprisingly good condition – despite the large patches of rust that covered its hull, mixing with the faded olive green and giving it the appearance of a deliberate camouflage pattern.

Two sturdy but lean young men climbed out of the cabin, tugged their heads between their shoulders, bent over, and moved hastily towards the small group of elders waiting for them at the edge of the clearing, their mismatched camo fatigues fluttering as if the wind wanted to rip them straight off their bodies. A few paces before reaching the waiting assembly they slowed down and scanned their opposites’ faces. They approached the waiting group of elders, suspiciously eyeing the makeshift weapons they clutched, an uneasy expression on their face. One of them, the taller one, had a pistol holstered on his hip, but Hector doubted there were any bullets in it. Factories stopped producing when the supply chains collapsed well over a decade ago, and ammunition had been one of the first things to run out in the months after – at least in their part of the world.

The shorter one, a barrel-chested, flat-nosed, dark-skinned fellow of around thirty years – a Southerner, probably, Hector thought – cleared his throat noisily, and began to talk in a nasal singsong, barely audible over the roar of the engine:

“Greetings to you all! We saw the smoke from your fire, and we…” he began, “we are delegates of the New Ayutthaya Republic,1 and we come to establish trade…”

“You’re what?!” someone shouted over the ear-splitting roar that still filled the clearing and echoed through the trees deep into the forest.

“Delegates, ahem, from the Republic of New Ayutthaya,” the taller one repeated loudly, while the motor of the helicopter slowly started powering down.

The elders waited for the rotor blades to stand still, spears, staffs and machetes in hand, while the two delegates awkwardly stood there and scanned their surroundings. It was getting really hot, and the air simmered above the barren ground of the clearing. One of them eyed Hector for a second, but, suspecting nothing, continued to move his gaze uphill towards his house.

“What’s your business,” demanded Uncle Mun harsh. Uncle Mun was not very tall himself, but his broad shoulders, strong, muscular arms and weathered face, gave him a formidable appearance – especially when he was angry.

“We mean no harm, uncle,” the taller one said reassuringly, using the respectful traditional title for addressing a man who’s older than you, “we hold no ill intention!”

“What’s that for, then?” he asked, pointing at the pistol.

“A measure of caution, s’ all.”

“Caution of what?!”

A third person, the pilot, wearing the typical dark-visored aviation helmets of the last century, climbed out of the cabin of the helicopter, and made his way towards the small group at the edge of the clearing. He was wearing a dark green jumpsuit, completing the typical pre-Fall pilot look, and where his right hand should have been, a stump protruded from his sleeve, on which a sort of metal claw with two fingers was mounted as a primitive prosthesis. Slowly, the other villagers emerged from the safety of the surrounding green thicket and walked hesitantly towards the massive machine parked in the middle of the village square.

“You never know,” the shorter one replied with an apologetic grin, “it’s pretty crazy out there.” He waved his arm over the dense forest down in the valley – their fruit and nut orchards, indiscernible from the jungle surrounding it, especially from above.

“Says the guy who just fell from the sky.”

“Enough, enough,” interrupted an old woman called Fon, brushing aside Uncle Mun’s concerns with a wave of her hand, “let’s hear them out!”

“Alright, but only if they leave that thing where it is,” Uncle Mun grumbled, motioning towards the holstered pistol.

After the other elders had finally finished introducing themselves and exchanging courtesies and superficial questions that Hector couldn’t hear from where he stood, they invited the two delegates and the pilot to share a meal with them, and led them up the hill, through the grove of milk trees, to Yaem’s and Hector’s house. They are too damn lucky, Hector thought to himself. He and Yaem had kept a rare treat in some burlap sacks stowed away in the corner of their kitchen: the first few dozen wild durian since the beginning of the last suncycle! The first fruits to drop always took a few days to ripen, but the strong smell they soon started emitting was always the unmistakable sign that they were ready to eat. Yaem and Hector had intended for them to be a surprise, to be savored after the day’s important meeting, but this morning the first visitors had already asked them about that strange stench, somehow slightly repulsive, but yet so familiar…

“Could it be?” he had heard them whisper as they made themselves comfortable on the wide, knee-high table made from bamboo slats that stood under their house.

“No, it’s still too early, they wouldn’t turn ripe for another month!” someone else answered.

“But I could have sworn that I just smelled durian!”

Yaem had dispelled their suspicion by lying that one of the cats had vomited up raw eggs, which, admittedly, smelled similar to some of the polyphenols giving durian its distinct flavor, at least to some people. Good call – you could definitely sense the similarity between the two smells, and they probably contained a similar compound, Hector had mused afterwards.

They had just finished eating lunch when the helicopter arrived, and there were still some boiled plantains, chili paste made from fermented fish, and a bit of dark-green bamboo shoot soup simmering in a pot above the stove, and Tak, Uncle Mun’s eldest son, fetched the guests a banana leaf to use as a plate and a calabash as a bowl. The trio ate hastily, uneasy, as if they hadn’t had anything to eat the whole day – or as if they were in a rush? – but Hector could tell by their expression that they really enjoyed their food. And how could they not? Right now was one of the much-anticipated periods of plenty where there was the most diversity in their diet, the end of a long raincycle, when there was finally enough sun for all the delicate vegetables to be sown that would have drowned or get washed away during the mutant of a monsoon they had just weathered. Even better, it was fruit season – many of their fruit trees had taken to fruiting whenever the cycles changed and there was both ample rain and sun for a few short months.

Admittedly, Hector thought, would the two delegates have arrived a few weeks earlier, they would have probably had the same boiled bananas and bamboo shoots, but with much less additional ingredients and flavors. Nonetheless, he felt proud that their community could offer unannounced visitors such a lavish meal. Such abundance was a rare thing to encounter these days.

The pilot seemed especially hungry, eating hastily and even asking Bay, Tak’s wife, for another bowl of soup – twice.

“Do you have electricity at all?” the shorter one (who had told them in the meantime that his name was Dam) asked, loudly chewing, before shoveling another handful of steaming bamboo shoots into his mouth.

“Yeah, occasionally,” Tak answered hesitantly. Spare parts for generators, inverters and charge controllers, and especially solar panels or old batteries were rare (and thus very valuable), and they had theirs hidden on the roof of their highest hut, which happened to be Tak’s ‘Watchtower,’ as he affectionately called it. This way the panels didn’t get hit by flying debris during storms, and occasional traders or other visitors wouldn’t see immediately that they had electricity. Rumors circulated widely, and a community that was too well-off would surely invite scavengers, thieves, raiders, or worse.

The Watchtower was a masterpiece of primitive architecture: a sturdy frame of highly flexible bamboo stems and walls of woven bamboo paneling, topped by heavy sheets of thatch layered with plastic tarp, sewn together with rattan twine and reinforced with thin metal rods, the whole arrangement tied together with what must have amounted to kilometers of vines and old wires. Apart from Bay and Tak himself, people didn’t usually dare ascending the bamboo poles that lead up to his tree house, which stood about fifteen meters above the ground, nestled into the branches of the towering grey monolith that grew on the hillside behind Hector’s own house. Sometimes, when they looked up to it during a thunderstorm, lightning illuminated the sky for a second and they could see the Watchtower, high up in the old somphong tree, a slender, black stick figure in front of the bluish-white clouds, swaying in the wind like a crazy, old drunk on his way home. They always asked themselves how Tak and Bay managed not to fall out of their hammocks and roll overboard, but the next morning, they always both descended the bamboo ladders with a wide smile, and – upon enquiry – both confirmed that, thank you, they had an excellent night. True Treeclimbers.

But today, they had to be extra careful with what they told about ourselves, because, as Hector surmised, if this group from Ayutthaya had a fucking helicopter, they might have other, more concerning things as well.

“How do you manage without?” Dam wanted to know.

“What a question! No other animal needs electricity, so why would we?” quipped Jaak from the other corner of the table. He gave Hector a wide grin and Hector winked in response – my boy!

Dam gave him a confused look and continued his inquiry: “What about your equipment, machines and stuff? You need some power source, or not? How do you farm, how do you build things?”

“The Great Mother provides, and we accept Her gifts gratefully. It is in Her that we find strength, joy, and fulfillment, and it is Her will that we follow,” Tak replied, reciting the beginning of their thanksgiving prayer.

“May Her power be everlasting,” added Jaak with a mysterious smirk, imitating Dam’s heavily accented pronunciation of the word.

Dam looked around helplessly, and the second delegate, Peet (or maybe Pete?), who had stood up to rinse his slender hands with water from the earthen jar next to the table, began to address the small crowd gathered under the house.

“Look, we are not spies. We did not come here to rob you. Do we look like we are particularly needy?” he asked, nodding towards the helicopter in the clearing below. “We are the ones who have something to offer, and you’d be wise to hear us out.”

Peet uneasily shifted his weight from one foot to the other, then crossed his arms. Upon insistence from Uncle Mun, he had left his pistol with the pilot – who could probably not draw it quickly enough with the crude metal tongs he used as a hand – and he had instinctively tapped the place on his hip where it usually sat, twice already. They were getting nervous.

Creating a good bit of confusion was part of their protocol for encountering strangers. The most important thing was to show group cohesion, and it worked wonders if they gave off a strange, cult-y vibe that people had difficulty pinning down. It irritated folks, and gave them the unsettling feeling that they were up against something big, a people that they didn’t understand and thus better didn’t mess with.

“And we will,” Fon said calmingly, brushing a streak of silver hair out of her face, “but not while we eat – and not in this heat! We will arrange a meeting this evening – I assume you want to stay in our camp for the night?”

Peet nodded, visibly relieved that there was at least one person willing to have a normal conversation.

“We’d be honored.”

Any other group would have probably swarmed the helicopter in amazement as soon as it touched down, and they would have welcomed the ambassadors with open arms, like saviors, and hung on their every word. Not them, though.

Not the People of the Rattan Vine Mountain.

Durian, once called the “King of Fruit” was a rare luxury these days, even though the land they inhabited used to be covered in durian plantations before the Fall. Most of them fell victim to the first suncycle, and today only a few large wild durian trees survived in the deeper and darker valleys that had small streams running through them even at the height of a suncycle. The durian trees fruited irregularly and often without any discernible schedule now, so durian was a real treat, a special occasion worthy of a small celebration.

What better way to assure the two delegates of our good intentions, Hector thought.

Some of the younger kids had only ever tasted durian once or twice, and the excitement had been growing over the last few months as the fruits grew to the size of a volleyball. A few days ago, Uncle Mun had found the first few fruits under one of the massive durian trees that grew next to the pond, at the bottom of the ridge that ran down the mountain besides Hector’s house.

The pungent smell of ripe durian wafted through the air as the first fruit was elegantly split in half by Bay to reveal the soft, creamy, deeply yellow flesh. The two delegates, who had been talking quietly among themselves in a corner, were on their toes now, trying to get a glimpse of the source of this strange odor that everyone seemed so excited about. The pilot had already excused himself and left, to take an afternoon nap in the helicopter – or so he murmured. Hector could see that he was worried, maybe about children climbing around in the cockpit and messing with the instruments. It must have been a hell lot of work to maintain such a machine for so long, so he could understand the pilot’s concerns. Hector wouldn’t have felt too good about a bunch of children using it as a playground either, and between the trees they could see the helicopter standing in the middle of the clearing, like a strange, alien artifact from a different world, a kid dangling from its tail.

The first few fruits of the season were usually not the best ones. They tended to ripen unevenly, one half creamy and sweet and the other still crisp and firm, but today they were lucky with the first half dozen fruits: only one was a bit underripe, and all were gone within seconds. They ate in silence, grinned at each other with full cheeks, savoring the heavy, sweet flesh with the texture of molten cheese, and for the first few minutes the only sounds were the smacking of lips and the occasional, delighted “hmmmm!” when somebody shoved another piece in their mouth.

Once they started eating durian it usually became really difficult to stop, so eventually the small assembly went through two entire sacks, probably about three dozen fruit in total. Yaem collected the pieces that weren’t fully ripe in a woven rattan basket, to be used as an ingredient for dinner, and hung it under the thatched roof of their porch, out of reach of children and pets.

After this special dessert they decided to sit outside for a bit, and, resting on the ground under the lychee tree next to Yaem’s house on mats woven from banana fibers, they quietly admired the clear view of the mountain range rising out of the mist in the valley. The afternoon heat was oppressive – a muggy, stifling haze that crept up from the valley and made the sweat trickle down their torsos, the heavy silence pierced only by the occasional clear, high-pitched cry of a hawk circling overhead. Their guests seemed tired, so they didn’t bother them with further questions and let them rest. To his own misfortune, the pilot had missed the best part of the meal, but Yaem had saved a few pieces of ripe fruit for him.

Durian was considered a ‘hot’ food that increased body temperature and drove perspiration – and here they sat, sweating profusely in the sweltering afternoon heat, tired and groggy from all the durian, and soon enough gourds of cool ‘Nana Ale, a slightly alcoholic ferment made from wild bananas in large earthen jars submerged in the ground, were being passed around.

Not long and the delegates, leaning against the massive trunk of a milk tree, dozed off.

When they woke, the sun had sunken below the tree line, and a refreshing breeze wound through the air, the coconut palms lining the eastern side of the clearing swaying softly.

It hadn’t rained in a few days, but there were still plenty of mosquitoes around dusk. The Firefeeders went to work, and soon the entire village was blanketed in soft, billowing clouds of fragrant cinnamon wood smoke, flavored with a herbal mix of green plants with mosquito-repellant properties.

Their village was a smattering of about two dozen makeshift huts and houses, mostly made from bamboo or wood, with thatch or metal sheet roofing, or both. They were scattered throughout the forest gardens that surrounded and overshadowed them, all within shouting distance of each other, on a hill above the creek, circled around the clearing where the helicopter stood. It might not have been the best idea to hack the clearing right in the middle of their village, Hector thought, but then again, nobody would have expected anyone arriving by air.

Together with Uncle Mun’s sequestered shack down in the valley south-west of them, the house in which Hector and Yaem lived was one of the few buildings that was a tad more remote, perched over the clearing, away from the cluster of huts below them on the steeper part of the first smaller mountain of the Rattan Vine Mountain range, and from his resting place under the lychee tree Hector could see more and more people walking around the helicopter towards the northern slope beyond the clearing, in the direction of the plateau where, under massive breadfruit trees, a larger structure stood: the Longhouse.

While their group was resting under the lychee tree, the few members of the Council present, Yaem, Mun, Fon, and an elderly woman with short, white hair called Jet, had decided to hold a meeting in the evening, after a shared dinner, and the children had dispersed in all directions to deliver the message to their families. A small group of people was now busy preparing food in the spacious communal house – a sour curry with the unripe pieces of durian and sliced banana corms – they had decided to eat together in the Longhouse, a bit downhill from the clearing by the side of the creek, on this special occasion.

There were a few dark clouds gathering in the east, but they would probably pass long before their payload got too heavy. Hector still lounged under the lychee tree and watched a pair of hornbills cross the sky above him, the unmistakable whooshing sound of their wings clearly audible, despite their height and the piercing sounds of screaming children racing around the helicopter. He tried to imagine what it must have taken to keep a helicopter operational for such a long time, the lengths to which people must have gone to make sure it was ready to use. Did they only have this one, or were there more? What was their purpose? Why actively seek out other communities, and why in this spectacular fashion? If you simply want to trade, there is no need to fly. No, this was a display of some sorts, and the implications were worrying.

Hector had been dead sure that the age of large machines was over, and gasoline didn’t keep longer than a few months. They must have found a way to produce gas themselves. But why waste it on helicopter trips?

He rolled some crumbs of the dark brown, sticky cannabis flowers the Wildtending guild mass-produced each suncycle into a dried palm leaf, lit it with an ember of the small, smoldering fire the kids had built in their midst to deter mosquitoes, and took a long drag. While the delegates were busy eating, he had stayed in the back of the crowd, and even during the durian feast he had Yaem bring him a few pieces to the bench besides the fireplace where he had crouched, his scarf still around his head. Thankfully, the delegates were too busy devouring creamy arils of ripe durian to take any notice of the unusually tall old man with the pale skin sitting on the sidelines, behind the crowd.

Ever since the climate had spiraled out of control (if that’s the right way to put it – was the climate ever “under control?”) nobody could be sure when one year ended and another one started by simply observing the seasons. They had collectively managed to disrupt the most regular and reliable natural cycles: the Polar Vortex, the Jet Stream, the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (the Gulf Stream), and the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, which all had started spinning off track in the 20s. Things started getting notably weird when the triple La Niña hit in the years 2020-22, and the climate deteriorated dramatically soon after. Hector remembered talking to friends and family on the other side of the globe via video call, many of them still deep in denial about the severity of the climatic breakdown unfolding all around them. There were unmistakable signs that the Gulf Stream was slowing down right after the turn of the millennium, that several tipping points had been breached, but many people continued to believe that some magic new technology – ‘carbon capture and storage’ was chanted like a mantra in developed countries – would be able to reverse those processes. Yet in the years leading up to the Fall, evidence had amassed that even if scientists invented the technology in time (and scaled it up big enough to have a global impact), atmospheric carbon was not like a thermostat which you could simply turn up and down, and temperatures dutifully followed. If there was any one thing that stood out – beyond the weekly exclamations of surprise that everything was happening faster than even the most experienced scientists had predicted – it was that people still knew precariously little about how different parts of the global climatic system interacted with each other.

The ‘Super El Niño’ of 2024-25 (the first time the temperature climbed above 1.5 degrees Celsius over pre-industrial levels) was what Hector considered the definite beginning of the end, at least in official debates. Yaem insisted that it was the Covid-19 pandemic that really signaled the end of an era, and convincing arguments could be made to support both stances. In fact, the downturn had made itself felt years before the first global pandemic, as became obvious from surveys that charted a noticeable and steady decline in people’s well-being and future outlook starting around 2016, although one of the refugees with a background in economics had insisted it was the financial crisis of 2008 that paved the road to disaster.

In reality, it was much more complex than this, but only Yaem and Hector understood how deep the roots of this problem really reached: to the shift from foraging to farming, when people first started to build larger settlements, modified the landscape on an enormous scale, and began perceiving themselves as better and more worthy than the other living beings with whom they shared their habitat with. But tell that to a bunch of farmers, Yaem occasionally lamented.

When they told the kids that there used to be a few months of rain, followed by a few months of sun, they almost wouldn't believe them.

“How easy life must have been,” Jaak once told Yaem when they were replanting windbreaks around their freshly cleared orchard, “You could just plant whatever you like, whenever you like, and didn’t have to worry about whether the plant will survive or not”.

“Indeed,” she had retorted, “gardening used to be child’s play! Stick a few seeds in the ground and wait, that was it. And durian every year!”

“Oh, the good old days,” Jaak mocked, shuffling around like old person with a hunched back while using his machete as a cane, “gimme a break!”

How times have changed, Hector often thought to himself when he looked out over the valley. How fast, how drastically were the lives of their generation turned upside down, and how hard they were slapped in the face by reality catching up with a culture that had had its head in the clouds for too long… Well, they kind of had it coming.

Everyone, from the youngest to the oldest, showed up for dinner that night. There was excited chatter, interrupted only briefly when the two delegates and the pilot climbed up the carved log that served as stairs. They stood in the entrance and looked around for a moment, their gaze wandering aimlessly through the crowd as their eyes adjusted to the darkness, and after Yaem motioned for them to come over, they circled around the family groups sitting in small circles scattered across the floor and took seat in the corner of the house reserved for elders, where Yaem and some of the other older women had prepared a few pillows for them. Hector had settled himself on a kapok pillow in the circle of Tak’s family, a bit off the center, in the darker corner of the only walled side of the longhouse.

“There is no rush to let them know I’m a farang,”2 Hector told Uncle Mun, who had also decided to eat away from the other elders today and had taken seat besides his eldest son. Uncle Mun shot a quick glance at the trio, all three absorbed in their meals as if they never even had any lunch, and his bushy brows furrowed.

“Sure means trouble, if you ask me,” he finally answered. “I mean, a helicopter, after all those years? How do they even keep a machine like that running for so long? Where the hell did they get enough gasoline to fuel that thing? What kind of community decides that a top priority is the maintenance of a damn helicopter?”

“Not sure we’re their first stop as well,” Bay added. “How many places did they visit before coming here? We’re probably hundreds of kilometers away!”

Tak nodded slowly. “Not sure if it was the community that decided to keep the helicopter,” he said thoughtfully. “Free people usually have better things to occupy their minds with.”

Once the food was served by the younger boys, as was customary, they ate in silence, interrupted only by the occasional remark on how well seasoned the food was, or how one or another kind of vegetable really complemented the taste of the dish. Hector saw Jaak whisper something to Yaem when he bowed down to place the tray in the middle of the elders’ circle, and Yaem frowned for an instant. She immediately caught herself, and took a quick look around to see if anyone had seen her slip. When their eyes met briefly, she gave him a reassuring smile, but there was undoubtedly worry in her expression.

Tak finished his meal and lit a palm leaf joint, a muan, as they affectionately called their slightly inebriating cannabis cigarettes, and handed it to his father after a few puffs, who had also emptied his plate in the meantime.

After the meal, the sour curry served with steamed cassava, boiled yams and a thick green herbal soup, they all gathered in the small clearing in front of the longhouse. The Firefeeders got busy, fetched a few large logs, and soon a tall fire was blazing in the ceremonial fire pit, the flames dancing excitedly and throwing waves of bright-glowing sparks high up into the night sky.

Hector couldn’t wait to hear what the delegates had talked about with the other elders over dinner, but he pushed himself to wait a bit longer. He was also keen to hear what Jaak had whispered to Yaem, and his eyes scanned the crowd for the boy’s round face, but he couldn’t find him.

Something seemed off. He wasn’t sure what exactly, but the whole story seemed surreal, too much, as if past and present had intermingled to produce a tear in the very fabric of reality.

The Firefeeders’ main job was – as the name implied – to tend the four fireplaces that cornered their settlement on all cardinal directions. There were a lot of mosquitoes during the raincycle – a lot! – so they needed the smoke to make life somewhat bearable. The Firefeeders sometimes joked that they were presented with the choice between malaria and lung cancer, and it was their job to tip the scale in favor of the latter. Today, the wind had blown from the north-east – a sure sign that the seasons were changing – so the two fireplaces on the north and the east end of the village were set alight. The Firefeeders were also responsible for all firewood used for public purposes (each household collected their own firewood for cooking), the replanting of designated firewood tree species, and for the sustainable harvest of said materials. During the raincycles, once everyone had returned from their suncycle migration and the entire village had congregated again to tend to their gardens and wait out the rain together, the fires were left burning at almost all times. Large logs of slow-burning wood were fed to the voracious fires over the seemingly endless wet months, and over the course of each day the Firefeeders periodically added green branches, creating thick columns of white-blue smoke that swirled through the trees like dancing ghosts.

The old woman named Fon, a Seedkeeper, spoke up first. Fon (rainwater) used to be a common nickname for people – but not anymore. The rain wasn’t a blessing anymore, at least it stopped being one soon after the first month of rain soaked the thirsty soil after a seemingly endless suncycle. After that, rain became a curse. The relentless downpours soaked everything and everyone, until the feeling of dampness became your constant companion: only damp clothes to wear and damp blankets to sleep under. In former times, people used to say that ‘rain brings life’ – and it did! – but now it could also easily bring death. One really didn’t want to be caught in one of the many narrow ravines when the grey wall approached, because within minutes entire valleys transformed into roaring rapids, uprooting trees and carrying logs the size of coconut trunks.

An ancient folk belief posited that nicknames always inferred something about the character of a person, and this was undoubtedly true for Fon: while everyone else was cursing and running for cover when another grey wall approached, Fon never hurried, and never stopped whistling her favorite old luk thung tunes, strands of silver hair sticking to her face, a bastion of calm even during the wildest storms. Her aura had earned her the unofficial title of being the facilitator and mediator of their camp, and she was the spokeswoman during most of their meetings.

When everyone had settled in a large semi-circle around the fire, she motioned the crowd to be silent with a wave of her hand, and the chatter abated in an instant.

“So, what is it you need?” she asked the delegates, who were standing besides her, after a dramatic pause.

“It’s not like we need anything, but more about what we have to offer!” the taller one, Peet, smirked, “Gasoline.”

A surprised murmur went through the crowd.

“We thought that the infrastructure was damaged beyond repair?” Hector asked, stepping into the wide circle illuminated by the fire. He had tied his scarf around his waist in the traditional manner, which – apart from an old pair of shorts – was the only piece of clothing he wore.

The eyes of the delegates widened for a split-second as soon as they recognized him as a foreigner – but, as their culture had mandated for so many centuries, they caught themselves immediately. Never openly show your feelings to strangers. Someone who hadn’t paid close attention wouldn’t even have noticed, Hector thought.

The last years before the Fall Hector had been in contact with some of the ‘eco-terrorists’ responsible for attacking oil infrastructure, in concert with larger underground organizations, some of which had operated globally and thus caused sleepless nights for those in power. On some occasions they had harbored fugitives, saboteurs who had ascended to the top ranks of the government’s ‘most wanted’ lists and needed to stay off the radar for some time. Their place was perfect – largely self-sufficient, no CCTV for miles around, only a single access road, the jungle in the back, and almost indiscernible from the surrounding forest from above – people could lay low for months on end without being noticed, and they could travel the secret trails along the forest edge or winding through abandoned orchards to avoid being spotted by high-altitude surveillance drones. They had stayed in a small, well-hidden tree hut most of the time, or helped them in the gardens when clouds blocked the view of the drones and satellites. All this now seemed a lifetime ago.

Hector knew first-hand that the hastily erected pipelines had been repeatedly bombed along unguarded stretches and critical nodes long before the oil tankers stopped coming. The government had aggressively ramped up local production in an effort to keep what they deemed “critical infrastructure” running – mostly border checkpoints, military and border police garrisons, as well as the heavily fortified gated communities that had sprung up after the first failed harvests of the 20s and the concomitant social turmoil. After decades of foot-dragging for fear of fierce local opposition, ‘fracking’ had finally made one last frantic comeback as the last environmental laws regulating the national oil industry were overturned in an instant.

The pipelines were a catastrophe from the beginning on: to the detriment of the locals, they leaked every few kilometers, as the ground below them had shifted a few centimeters in the first rainy season after their construction already. Shallow concrete foundations had been poured, often into soaking wet ground, and the construction sites had to be heavily guarded against protests by local opposition that flared up time and again.

Those massive iron serpents, surrounded by coils of razor wire on all sides, ran along the major highways for the most part, which made both surveillance and maintenance easier, but crossed densely populated areas occasionally. Reactions were mixed. Some people, sensing opportunity, eagerly collected every drop, which they refined in hazardous backyard refining operations that regularly blew up, sometimes killing dozens of people. A positive side effect was that the resulting environmental nightmare mobilized ever more people to join the Greenshirts, a broad, leaderless political movement with cadres in almost each district, some of which had elusive underground cells that operated nation-wide.

“We’ve managed to keep a few wells functioning over the entire last dry period, much longer than any time before that,” Dam started, but Peet interrupted him impatiently: “…and this year it lasted us until the heavy rains were over – until now, in fact!”

“Oil was the reason we were able to conquer the world, so oil will be needed to rebuild what we’ve lost,” Dam explained.

“And now we’ve finally started to produce enough to begin expanding,” added Peet with a satisfied grin.

“Where the hell did you find oil?!” Uncle Tip, the only mechanic in the village, inquired sharply, “I thought the government depleted all onshore national reserves?”

“Not all of them, only the most productive ones. We were left with the smaller and deeper-lying fields, and it was one hell of a task to pump it out.” The pilot, who still hadn’t told anyone his name, was on his feet now, waving his metal claw to emphasize his point. “We had to use electric motors to run the pump jacks in the beginning, and we were barely able to extract crude by the liter. The small pipes clogged frequently due to lack of maintenance, so it took quite a few months until we had enough fuel to run the larger pumps. In the beginning we barely broke even, but after some experimenting, we managed to restart the injection pumps and flood the reservoir with water and leftover polymers in order to…”

“Enough, enough,” laughed Uncle Tip, “I get your point. You’re a clever lot, and now you will rebuild civilization.”

A few others chuckled. The pilot looked slightly hurt, but continued:

“It is nowhere close to the EROI of former times, but it is a beginning. Back in the days, the fields would have been considered done with, but economic feasibility is not an issue when you’re the only one far and wide who has oil. You can’t imagine the prices we fetch per barrel!”

“We can run all kinds of machines now,” added Peet proudly, “and as soon as the rains stopped this year, we sent teams to Nakhon Sawan to survey the fields there.”

“As far as I remember, Nakhon Sawan is nowhere close to Ayutthaya! I thought you said you were from Ayutthaya?”

The question came from a young boy called Sun, the Thai word for ‘short,’ who had taken a keen interest into the collection of maps Yaem and Hector kept in their library during the teaching sessions they held last Suncycle.

“Now, somebody did their homework,” Dam said approvingly, “but we’re from Suphanburi. Only a few hours West.”

“That’s why we called our city New Ayutthaya. Better than the old one. More streamlined, better organized, more efficient, more modern,” added Peet.

Tak couldn’t contain a sudden burst of laughter.

“Sorry,” he panted, “but didn’t that work out just excellent the last time?”

Now Uncle Mun was laughing as well now, and a few others joined, Hector among them.

The name Ayutthaya derived from an ancient Sanskrit word which meant something like ‘the invincible (or the undefeatable) city,’ and this had provided Hector and Tak with a running gag they made sure to exploit on each opportunity: with their overambitious development projects in Ayutthaya, the government had tried to hastily cobble together a ‘new old capital’ a bit further upstream from Bangkok – which was already hopelessly overcrowded and severely flooded several times a year throughout the 20s, sometimes completely disabling traffic – so when the Chao Praya River broke its banks and repeatedly flooded most of Ayutthaya as well, public opinion turned sour. This was only to be expected, since Ayutthaya had been severely flooded already in 2022, when most of its much-famed historical sites had been inundated, much to Hector’s delight. Only the Earth lasts forever, he had laughed when parts of Chiang Mai’s ancient city wall had collapsed during the same period of heavy rain, brought by the triple La Niña of the early 20s. The government, as always more concerned with promising and chasing pie in the sky than with reality, had made last-minute plans to relocate crucial government infrastructure to Ayutthaya in the late 20s – shortly after Indonesia had finally started relocating most of Jakarta to Borneo to escape rising sea levels and extreme cyclones – when it became obvious that the rising waters steadily invading Bangkok wouldn’t recede. Parts of the inner city were bulldozed haphazardly, and a few presumptuous skyscrapers started shooting towards the sky, just to be abandoned after funding dried up because government funds had to be diverted to provide relief during yet another failed harvest.

As early as 2019, there were studies predicting that, by mid-century, Bangkok would be flooded almost entirely. But, as usually, the government had acted as if the traditional Asian meme of ‘see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil’ would be enough to deter the threat. And, as always, scientists were ‘caught by surprise’ by how fast the sea level rose, following the ‘unexpected,’ ‘shocking,’ and ‘premature’ first ice-free arctic summer in 2032. Ayutthaya became the textbook example of failed government efforts to stem the (literal) rising tide of climate-related problems, and to top it all, the government’s slogan was: ‘safer, stronger, better.’

Henceforth, Tak and Hector had turned the city name into a verb, and each time someone made big promises that he obviously couldn’t keep, bragged about future achievements, or simply overestimated his capabilities, he was said to be ‘ayutthaya-ing.’

The delegates looked as uncomfortable as if someone had stolen their clothes after a bath, and only after the laughter had abated and Tak had excused himself did they continue, visibly bewildered by this strange reaction from an even stranger people.

“We’ve had a massive influx of refugees from the capital, and we’ve managed to build up a decent little city there,” Dam continued, “we have specialists for farming, engineering, construction, mechanics, maintenance; we organized teams to dig trenches, built fortifications, and reinforce walls...”

“As a protection against the weather!” Peet interjected. Dam, eyes narrowed, shot him a quick look and continued:

“Right. We were able to salvage enough machinery to keep the necessities running steadily, and by now we extract and process enough crude to cover our own needs, and a small surplus.”

“What do you people eat?” Uncle Mun was suddenly standing, a skeptical brow raised. “If your ‘city’ is so big, you surely must farm a lot?”

“A lot of catfish, farmed in the ditches crisscrossing the settlement,” explained Peet, “and we grow EDR – enhanced deepwater rice.”

Hector watched Yaem’s face scrunch up in disgust.

“We eat plenty of meat, as well,” Dam added proudly, “We even grow Jasmine rice and other traditional cultivars on floating paddys!”

“And during the dry periods we farm crickets and cultivate sorghum.”

‘Enhanced deepwater rice’ was the brainchild of Kasetsart University: a quaint local Vietnamese rice cultivar with stems of up to several meters length, nicknamed ‘floating rice,’ had been genetically edited for massively increased yields and a number of other traits considered ‘desirable’ by the researchers. C4 photosynthesis pathway, increased salt-tolerance, drought-tolerance during the seedling phase, stronger cell walls, Beta-carotene content, Aluminum resistance, insecticidal Bt genes – even a gene sequence from the water hyacinth was successfully inserted, giving the plants’ internodes their enhanced floating ability. Nothing was sacred, nothing was off-limits in their feverish race to win the war against our own Great Mother Earth, thought Hector.

In the years leading up to the Fall, the government had promoted EDR as a revolutionary new staple crop for areas affected by heavy flooding, and aggressively pushed indebted farmers to serve as guinea pigs in hastily conducted field trials: they were forced to experiment with growing and consuming this new variety, without any compensation for possible adverse effects. It’s either that or you lose your land, the government told them. But as far as they knew, EDR was never sufficiently tested in real clinical trials, and people who ate a steady diet of EDR started exhibiting a variety of inexplicable neurological and autoimmune symptoms soon after.

Even worse, in many instances the entire crop was just washed away by the biblical floods, because the roots couldn’t penetrate the dead soil deep enough to be able to resist the relentless pull of the water.

Catfish, soon dwarfing both chickens and insects as the undisputed number one source of dietary protein, were increasingly farmed using raw sewage as additional feed in the years preceding the Fall – a practice the Chinese had secretly used since the early 2010s to help feed their ballooning population.

“If you are interested, we could take your leader for a tour,” said Peet, intent on appearing as casual as possible to avoid any suspicion, “a week and you’ll be back here. How’s that sound?”

His question was met with grave silence. Dam smiled sheepishly, and the pilot scratched his forehead uneasily with his remaining hand. This was not what they had expected, and probably not what they had experienced during previous encounters with other groups, if there were any.

The problem was: they didn’t have a leader. Their village had a mixed committee of elders, the different guilds that convened from time to time, and a general forum each time a larger issue came up. There were several influential people, Fon and Yaem usually leading the way, but there was no way even for the most respected community members to coerce anyone. Hector and Yaem had made sure that the tendency to blindly obey alleged authority, the ‘slave mentality,’ as they called it, was eradicated as soon as the state became weak enough to become confined to the urban centers and their periphery.

After what felt like minutes of awkward silence, and after dozens of questioning looks had been exchanged, Yaem rose to speak.

“This is not an easy decision to make, and we will tell you our answer in the morning. It is getting late, so this will be the end of it. You’re welcome to sleep in the longhouse, we have prepared a mosquito net for you in the eastern corner.”

People nodded approvingly. It was obvious that this might easily be a trap, but equally obvious that it would be much too obvious for a trap. Moreover, the delegates wouldn’t gain anything from kidnapping or killing the leader of a small community hundreds of kilometers away from their base. If what they told them was right, they very likely didn’t need anything their small village had to offer, so raiding was also out of question as a motivation. Even the children had fallen silent momentarily, sensing the seriousness of the situation, as people quietly began to discuss what, in their opinion, the best move would be.

There was one more thing Hector had taken issue with: they used the old terminology, pre-Fall, of months and years.

“So, what year do you think it is,” he asked hesitantly.

“Well, we don’t think, we know!” Peet gave Hector his widest smile, revealing his missing premolars, “Two-five-nine-two!”

Larger numbers were long, complex words in Thai, so most people used a series of single digits to numerate years. Two-thousand-five-hundred-and-ninety-two. 2592. The words reverberated through Hector’s mind. The Buddhist calendar is set 543 years after the Common Era, five-four-three, easy to remember.

Hector could swear that he felt the sensation of an old, rusty engine being started after a long time as the numbered wheels in his neocortex started creaking into action. Minus four is five, minus three is nine, so five minus one more because…

“2049.”

Just after everyone had lifted their eyes to him did Hector realize that he had spoken the number out aloud. Endless raincycles of internal torment over the question of whether he wanted to know the date or not, and just as he had finally started making peace with the fact that he might never know to what age he would make it, those two bastards ruined everything with their fucking linearity.

Hector had heard enough. He turned around abruptly, grabbed a burning ember as he passed the fire, briefly nodded to Yaem, and started walking uphill, towards the clearing where the helicopter stood, and to his house on the hillside beyond. As he passed the helicopter, the light of his improvised torch reflected back from the glass panels of the cockpit, lighting them up like the eyes of a giant wild cat in ambush, just waiting to launch forward.

Somewhere in the forest below, a lone bay owl was singing her melancholic song, a series of four descending whistles followed by four echoes of the last note, each rising like a question that would forever go unanswered.

Click here to read Chapter Two: A Rude Awakening

I write stuff like the above in my free time, when I’m not tending the piece of land we’re rewilding here at Feun Foo. As a subsistence farmer by profession I don’t have a regular income, so if you have a few bucks to spare please consider supporting my work with a small donation:

To access the following chapters of this story, please opt for a paid subscription or upgrade your free subscription to a paid one:

If you want to support our project on a regular basis (and thus help make this story become reality), you can become a Patron for as little as $1 per month - cheaper than a paid subscription! - and gain access to the next installments of this story:

All names, characters, places and incidents mentioned in this story are purely fictitious. No identification with actual persons (living or deceased), events, places, institutions, and products is intended or should be inferred, and resemblance is entirely coincidental. Images used are either from the author’s personal collection or random pictures found online and distorted beyond recognition, and are thus beyond the scope of any reasonable claim of copyright infringement. No type of AI has been used in the writing, processing and editing of this text, or to create or edit any of the images contained herein.

The full name of the “New Ayutthaya Republic” used by the delegates is the formal term สาธารณรัฐพระนครศรีอยุธยาใหม่ (pronounced săa-thaa-rá-ná rát phrá ná-khawn sĕe à-yút-thá-yaa mài), which is, as so many Thai place names, hopelessly complex, unnecessarily long, and too cumbersome to pronounce for non-native speakers. In the text of this story, this is abbreviated to the (admittedly rather awkward-sounding) direct translation of the term.

“Farang” (ฝรั่ง, pronounced fà-ràng) is a common informal term, sometimes used in a derogatory fashion, that refers to Westerners, particularly Caucasians.

Honestly, this is pretty good. Would read the whole book. It remnids me a bit of Return by Clayton J. Elliot in how it portrays the post-collapse state of the world (though that book deals more with pre-collapse and collapse). I like that it takes into account all the local specifics; there are many works out there that don't, and feel sloppy. This has potential.