Where we go when we die

A materialistic reinterpretation of Reincarnation --- [Estimated reading time: 30 min.]

Disclaimer: I’m not a philosopher, obviously – meaning I don’t hold a state-certified degree in philosophy – so please excuse me if I juggle with concepts that some big-bearded, world-famous, long-dead philosopher has decided are not the same, partly because – as I will explain below – I don’t think that for the purpose of this discussion those differences matter much. Call me ignorant, but I don’t care much for the vast bulk of philosophy. To me as a primitivist, much of what constitutes the field of philosophy are the confused musings of oversocialized, hyperdomesticated and alienated modern humans, and their musings are merely a symptom of this alienation, the separation from Nature, that the people of this culture have experienced for the past few millennia.

Indigenous people have had very little use for what we’d call philosophers, because they are – unlike members of the dominant society – not eternally plagued by existential questions. They know their place in the universe, they know why we are here, what our purpose is, and where we are going. Their cosmology makes sense in itself, and it can answer each ever-so-abstract existential and metaphysical question they can come up with.

The main reason for my disdain for philosophy is that by far most philosophers have historically had a skewed or entirely false perception of human Nature, since almost nobody in civilized cultures correctly assessed the natural state of humans, and nobody cared to include the overwhelming majority of time we humans existed – ninety-nine percent of our existence, mind you – into their conclusions. We didn’t build cities and monuments during those millions of years, and if there are no pyramids and palaces, the cultures in question seem too alien and too primitive for the megalomaniacs that lead this culture, and who arrogantly take themselves to be the standard gauge of intelligence and technological sophistication.

Yet you learn very little about animals when you study how they behave in captivity, removed from the environment that shaped them – similar to how a potted house plant doesn’t tell you anything about the myriad kinds of reciprocal relationships the plant would enter and the constant conversations she’d have if she would be allowed to grow outside, in her native range, as a part of a vast, interconnected interspecies community. And that’s ultimately what civilized humans are: caged animals, potted plants.

All famous classical philosophers are victims of The Great Forgetting,1 and thus their findings are rarely stable and universally applicable, are always up for discussion and reinterpretation, and furthermore often lose their validity as soon as society changes again or new information is obtained, which happens faster and faster.

So, without further ado…

Death might be the one thing that’s most feared by the dominant culture, yet it is also the one thing that none of us is able to evade. We all die, one way or another, sometime or another.

So, what happens when we die? There are as many answers to this question as there are cultures (or even individuals), and it’s impossible to say who’s “right” – if that’s even a possibility. There is no objective way of knowing, no experimental setup that lets us study what happens, hence all answers to this question are little more than opinions and expressions of creativity, and I’m not claiming any absolute truths here. I simply want to recount how I see death, and what I think happens to us.

This is a very personal issue for me, and I rarely talk about this to other people. As an Animist, being a missionary of any sorts is out of the question. We don’t impose our beliefs on other people, because healthy spiritual beliefs, just like healthy cultures, must arise from the land itself. To achieve cultural perpetuity, true sustainability, the two abstractions we call Nature and Culture must become one. Trying to convince someone in Europe or North America to worship Asian Elephants, Great Hornbills, Banana Clumps or Rain Trees only found in Southeast Asia makes about as little sense as for me to worship American Bison, Reindeer or Brown Bears – or, for that matter, the words of a Judean carpenter, a Nepalese hermit, or an Arab merchant. Only if my cosmology deems the Elephant holy and the Forest sacred do they have an equal footing in this world and are thus protected from exploitation. A religion that doesn’t hold the forest and its inhabitants sacred will sooner or later find itself inhabiting a desert.

Furthermore, my beliefs are not a mere appropriation of indigenous spirituality, but a personal creation, a work in progress, and a humble layman’s attempt at a synthesis between the scientific and the indigenous worldview.

At the risk of ridiculing myself, in the following I will attempt to give a glimpse into my own cosmology.

The Western world – or, better, the so-called “developed” world in general – has an extremely unhealthy relationship to death, one that’s gotten progressively worse over the past few decades as Capitalism broke up family after family, privatized and monetized care for the elderly, and removed most of us from actually experiencing the death of people in our community on a regular basis. The decline of spirituality of any kind is, in my opinion, a major reason (but obviously not the only one) for the despair, discontent, depression, anxiety and listlessness currently observed in all walks of life – but this phenomenon is probably most pronounced among younger people. Humans are inherently spiritual by Nature, and since every human culture ever documented was (or is) profoundly spiritual (except, of course, for the currently dominant culture), it is safe to assume that spirituality is a cross-cultural universal for humans. The logical conclusion is that the blatant disregard of spirituality has far-reaching (and mostly unpredictable) consequences.

Furthermore, teenagers these days are very rarely confronted with the uncomfortable reality of death, and the result is people who are so horrified at the prospect of their own death that it leads to such extremes as Peter Thiel’s quest to “reverse aging,” other tech billionaires who regularly eat baby food and spend millions of dollars annually to look about two years younger, and institutions like Calico Life Sciences, a subsidiary of tech conglomerate Alphabet whose goal is to “reverse aging” and to “defy death.”

Pop culture’s answer to this universally-experienced existential dread is to distract ourselves with cheap pleasures, bingeing and shopping sprees, pushing us to try to fill the void within us with a never-ending stream of consumer goods, when what we are really looking for can’t even be found in the material realm. Mother Culture tells us that we don’t need spirituality, because we have consumerism. Just don’t think about what happens after you die, but instead never stop scrolling, chasing “epic” experiences, creating “content,” superficially emerging oneself in other broken communities and increasingly homogeneous cultures as we float across the globe and through life, as Ghosts without a Shrine, but – despite all our efforts – still closer to the inevitable end with each passing day. Don’t waste time, though, because “this life is all you have.”

Pathology in a nutshell.

If death isn’t seen as something normal, as the inevitable outcome for all of us, whether rich or poor, animal or plant, people will start questioning and denying its inevitability and try everything in their power to escape it. One of the main motivations underlying the denial of death is that it seems so incredibly scary.

For a long time, I believed – like so many other alienated western teenagers – that death is simply the end of it all. The lights go out, and that’s it. You cease to exist. One moment you’re there, the next you’re just gone. Eternal blackness ensues, blackness that you can’t even experience because you simply stopped existing.

This erroneous and highly nihilistic belief is an underlying cause for the profound, subconscious psychological distress I’ve outlined in the last paragraph, and it gives rise to all sorts of connected pathological beliefs, most famously the notorious “YOLO” (for the few boomers who read this blog: “YOLO” stands for “You Only Live Once”), which often leads to hedonistic bingeing of cheap pleasures, shortcutting the brains reward system to cause even more profound depression and distress as soon as the steady stream of dopamine abates. It creates a sense of existential nihilism that no teenager deserves to grow up being immersed in, and the spiritual implications of this completely unfounded theory of death are much more destructive than we tend to imagine.2

In every healthy, natural human culture not even children are this deluded. Death is the unspoken part that completes the “Cycle of Life,” and everyone who’s not utterly alienated from the real world knows this. People still fear death to some extent, but they don’t make it their life’s mission to avoid it. That people these days even consider this a possibility is baffling and shows how alienated we’ve become.

In natural human cultures little children sit beside their grandparents on their death bed, and cry with the entire family once their loved one deceases. They regularly witness older members of their community die, just as they see other animals and plants die or being killed, and they incorporate death into their worldview accordingly. This is always accompanied with some story of what happens after you die, and those stories vary considerably. It is of utmost importance to teach children that death is not the end. Death is not merely a departure (or at least not exclusively) – it is also a homecoming, a returning to the source, and this means that when one thing ends, another starts.

Recently, scientists have – by chance – been able to record the brainwaves of a dying person, and the records showed increased activity in the brain (similar to dreaming or recalling memories) 30 seconds after the heart of the patient stopped. This was very likely the same phenomenon that’s responsible for “near-death experiences,” where people who were reanimated after being clinically dead report experiencing a variety of things like seeing themselves from above, or the famous “light at the end of the tunnel.”

When you die, one of the first things that happens (from a purely scientific perspective) is that your brain is flooded with a rich mixture of neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and various endorphins. It usually takes about twenty to thirty seconds for brain activity to start diminishing after the moment of clinical death when your heart stops beating. You go out with a neurochemical bang, so to speak.

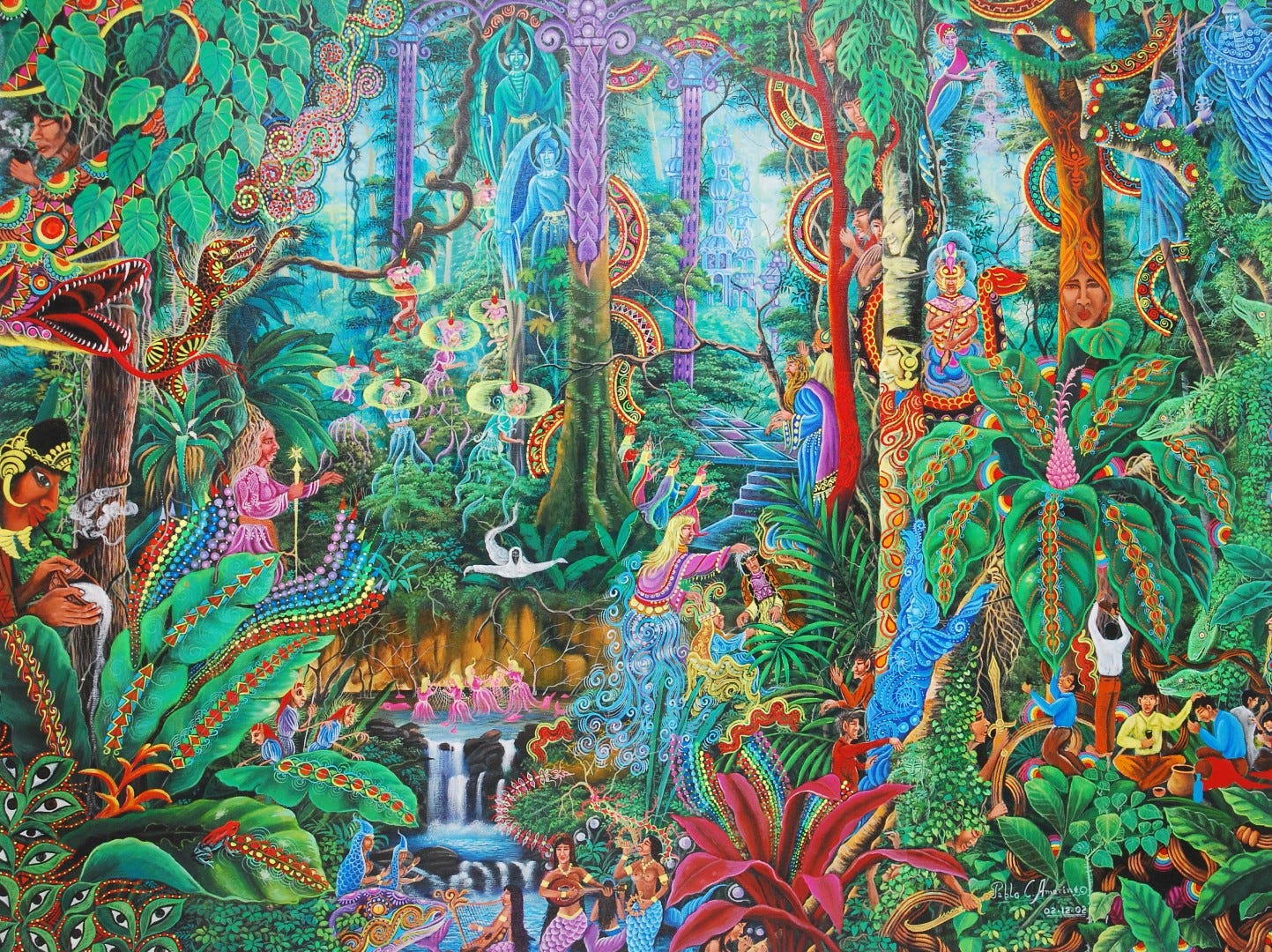

Anyone who has ever had a conscious-expanding experience with “heroic doses” of psychedelics – the group of psychotropic substances that includes psilocybin (the active compound of several species of fungi colloquially known as “magic mushrooms”), LSD, mescaline and DMT – knows what that means. It is the onset of a so-called “out-of-body experience”: it feels like our consciousness starts expanding or traveling far away (which might otherwise be described as “tuning into different frequencies” or “zooming out”), creating the illusion that we are not inhabiting your body anymore, or at least not only our body. With psychedelics, this is a mere simulation, a taste of what’s to come – with death, it’s the real deal.

I know that it seems like a terrible New-Agey cliché to start this story with talking about psychedelics,3 but from a scientific (and empirical) perspective the processes that happen in the brain during dreams, a psychedelic experience, and death are rather similar. The experience of being under the influence of psychedelics is almost universally described as including an intense and overwhelming feeling of “oneness” and “unity,” of the dissolution of boundaries between self and other, and of profound connectedness to everything that exists. The same sensations have been reported by people who had near-death experiences.

Experimental therapies using psilocybin or LSD to treat terminally ill patients have shown amazing results, taking away the fear of death almost entirely, often after a single session. In the moment we die our brain also produces dimethyltryptamine – DMT, dubbed “the spirit molecule,” is the most powerful known psychedelic – to the same effect.

When you die, this psychedelic out-of-body experience, this perceived transcending of the limits of your physical body, from you as an “individual,” this dissolution of any boundaries between yourself and the world around you is necessary for you to be able to grasp what will happen next. You will dissolve, quite literally, into trillions of tiny “yous,” while at the same time retaining your sense of self in each tiny fragment. You will shatter, and live on in the experiences of each such entity. This might seem like a paradox, but different rules apply to our lived reality and the spirit dimension that overlays it. Each and every one of them will be “you,” and you will soon realize that there’s much more of those tiny entities floating all around you – and they are all “you.”

Suddenly, you will realize – you will feel – that consciousness is shared, that (like the stereotypical cartoon hippie never fails to point out) “we are all one,” that the boundaries between you and all other living beings – and all matter, in fact – are illusionary and transient. It is the beauty of this realization that will cause you to tear up, to dissolve, to softly and slowly explode into tiny fragments, each being propelled outwards by the shockwave of the explosion, each gradually diffusing into the environment that surrounds you, like leaves of tea in hot water.

Our own individual consciousness is a transient phenomenon, an emergent property of the trillions of parts that make up our bodies, and once this synergistic fire is extinguished, our consciousness shatters, decomplexifies, and reorganizes at a lower trophic level.

You will experience the cosmic truth expressed in the ancient Chinese paradox called “when a white horse is not a horse,” to which Daoist sage Chuang Tzu famously responded:

Rather than use a horse to show that ‘a horse is not a horse’ use what is not a horse. Heaven and earth are the one meaning, the ten thousand things are the one horse.

What this philosophical gibberish means is basically that to show that “the horse is not (only) a horse (but more than that)” you might point out that the horse is also the grass, the river and the wind, since without grass to eat, water to drink and air to breathe, there would be no horse. The horse is made of those things, and although it might look like a horse to us, it is still “the ten thousand things” – a common Daoist metaphor connoting the material diversity of the universe, essentially meaning “everything there is.”

Self-proclaimed “philosophical entertainer” Alan Watts has argued that the idea of the separate and independent ‘self’, the illusion that we are “skin-encapsulated egos,” is a root cause of many of humanity’s biggest problems, which of course includes the ecological crisis. We think of ourselves as a monolithic entity, set apart from the environment we inhabit. It is this illusion of being a monolithic entity, a skin-encapsulated ego (that we mistakenly assume to be who we are), that diffuses and is being dispersed when we die.

Are we not also the mountains, the rivers, the soil, and the wind? Are we not also the plants and animals we eat, for without all those things we would simply not exist? The minerals that used to be the mountains now build our bones and tissue; the water that was the river now courses through our veins and cells; the molecules and organisms that constitute the soil are found within us; the winds that circle the globe now circulate through us. The living beings that gave their life for us are transformed and become us.

Who we are, our personality, what we might call our “ego,” changes with each minute, each second, and it is always the synergistic product of the compounds we’re made of at any given moment. Think about it: you are not the same person you were yesterday, last week, last year, and you are most definitely not the same person you were when you were a child. Since then, each molecule in your body has been replaced, so in line with the rather simplistic (but somewhat true) philosophical paradox of Theseus’ ship, can you say that you’re still the same person?

The building blocks that make up your body, that make you who you are, are in constant flux – you are exchanging those building blocks with your environment at all times. And this also means that your personality, your interests, hopes, dreams, values, wishes, ambitions, abilities, drives, fears, worries, and emotional patterns have changed. As we will see in a minute, they are two sides of the same coin.

Again, instead of bombarding you with scientific facts, statistics and research, I hope what I’m saying here sounds more like pretty basic common sense.

And we can take this a step further: wouldn’t you agree that if you were to lose a finger or a hand in an accident, you’d also lose a part of yourself, a part of who you are? Wouldn’t you be a slightly different person afterwards? It seems like a logical conclusion that if we lose a material part of our body, we also lose a part of our mind.

On a related note, this phenomenon also explains why recipients of organ transplants (especially heart transplants, since the heart contains a large number of neural cells) acquire personality traits of the donor. There is a part of who that person is in the organ, and a part of who you are is replaced by it during the surgery.

The idea that there is Mind and there is Matter, this outdated Cartesian dualism, is dead wrong. Mind is Matter, and Matter is Mind. There is no Mind without Matter, just as there is no Matter without Mind. It’s two sides of the same coin, and they can’t be separated.4 When you die, just as your mind is diffusing on a wave of endogenous psychedelic compounds during this last pulse of cocnerted brain activity, the same thing happens to your body, albeit the physical diffusion becomes more obvious only later on.

But they are one and the same process.

Small aggregations of matter have small minds, larger ones have larger minds.5 This is as true for animals (which we can understand the easiest) as it is for trees, and even for mountains, rivers, and other parts of the landscape that are, like us, in constant metamorphosis.6

A mind is more than a brain, and the brain is not the “seat of the mind,” as many people think. The mind – who we are – is a composition of everything that makes up our bodies at any given point in time, and thus is constantly changing, and never the same from moment to moment, day to day, and year to year.

Our bodies are in a constant state of transmutation, as things enter (usually air, water and food) and other things leave (less oxygenated air, urine, feces, skin cells, hair, etc.). There is a constant cycling of all sorts of different materials going on, and with it we change who we are at any given moment. Your body is made up of trillions of individual cells, and they are constantly being replaced. The average cell life differs widely. Skin cells have a relatively short lifespan of two to three weeks, red blood cells live for about four months and white blood cells more than a year, whereas some colon cells live only for four days. Basically, your whole body constantly flushes out old material and builds new materials out of the food you consume, the water you drink and the air you breathe.

Most parts of your body get replaced, and this new cell material is not made out of nothing: you are made of the food you eat – we will return to this insight in a moment. Both animal and plant bodies have roughly the same elemental composition (albeit with slight differences); our own animal bodies and the bodies of most plants as well are approximately 3-4 percent nitrogen by weight, and the bulk is made of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen. This also points to the fact that we are not so different from the beings we eat after all. We all descend from a common ancestor.

Moreover, our bodies also harbor immense amounts of bacteria, mostly in the gut. The total number of bacterial cells is larger than the amount of “human cells” that make up “our” body,7 although it is of course nonsensical to make a distinction, since those bacteria are a part of who we are.

The fact that our gut microbiome directly influences our mood, cognition and mental health via the “gut-brain axis” underscores the theorem I’m proposing here. We need certain bacteria in certain amounts to be healthy and happy – they are not only a part of who we are, but we need them to be whole.

A metaphor that explains the transcendental Nature of being, probably much better than the characteristically confusing utterances of ancient Chinese philosophers quoted above, goes as follows: Our life is like a wave in an ocean. Water molecules are not moving along with the waves, they are merely bobbing up and down as the ocean waves move through them. We are like waves moving through an ocean, always in motion and never consisting of the same compounds, while matter moves through us. Just a moment ago this molecule was a part of you, but now you have moved on and a new molecule has taken its place.8

Who we are is constantly changing. As molecules and atoms enter and leave our body, we acquire the personalities of those we ingest and inhale. Breathe healthy, clean air in a forest, and you’ll become more like the forest: refreshed, vibrant, balanced, vigorous and alive.9 Breathe smoggy air in an overcrowded city, and you’ll begin to feel just like that city: crammed, overwhelmed, stressed, artificial and polluted. The Guardian Spirit of the Land enters you with each breath, and changes who you are. Depending on if you are taking a walk in a forest or along a busy downtown road, you’re a slightly different person, with slightly different character traits.

Everyone knows this.

The same goes for food: if you eat good, fresh, local food, the food will become part of you. The personality traits of the animals and plants that you consume for sustenance will become part of your own personality, part of who you are. Think about it: let’s say you eat a big slab of factory-farmed pork each day – soon after, you’ll become more and more like the pigs you’re eating: you acquire their character traits and their personalities. They are unhealthy, unfree and unhappy, so if you steadily feast on their bodies, you, too, will start feeling less and less healthy, constrained and hemmed in, and you will slowly become just as restless, anxious, alienated, depressed, and desperate as those poor pigs – over longer timespans, the suffering of the factory-farmed animals you eat will be transferred to you.

Contrast that with consuming a wild boar: just as the animal in question was healthy, free and happy, those things will be transferred to you, and you’ll become more energetic, strong, robust, grounded, tough, and virile. The boar lives on within you.

The way this process works was probably best explained by Daniel Quinn in ‘The Story of B,’ in which he describes the beliefs of the indigenous Ihalmiut, who lived in the Great Barrens of Canada, inside the Arctic Circle:

Theirs was a strange life by our standards, but its strangeness makes it very easy for us to comprehend. The Ihalmiut were the People of the Deer. They were this because deer was what they lived on. They were completely dependent on the deer, because other animals were rare, and vegetation that’s edible by humans is practically nonexistent inside the Arctic Circle. It’s hard to imagine living entirely on meat—never a piece of bread, never a piece of chocolate, never a banana or a peach or an ear of corn—but they did and were perfectly healthy and happy.

They’d never have to explain who and what they were to their own children, but if they did, they’d say something like this:‘We know you look at us and call us men and women, but this is only our appearance, for we’re not men and women, we’re deer. The flesh that grows on our bones is the flesh of deer, for it’s made from the flesh of the deer we’ve eaten. The eyes that move in our heads are the eyes of deer, and we look at the world in their stead and see what they might have seen. The fire of life that once burned in the deer now burns in us, and we live their lives and walk in their tracks across the hand of god. This is why we’re the People of the Deer. The deer aren’t our prey or our possessions—they’re us. They’re us at one point in the cycle of life and we’re them at another point in the cycle. The deer are twice your parents, for your mother and father are deer, and the deer that gave you its life today was mother and father to you as well, since you wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for that deer.’

Another small anecdote I’d like to share in this context is what happens if you ingest common psychotropic substances, like cannabis and alcohol. As avid readers of this blog know, I’m a passionate fan of entering a symbiotic relationship with the cannabis plant, but, as people who know me personally can attest, I’m not much of a drinker.

As the smoke of the dried cannabis plant enters my lungs, particles that used to be plant matter, the body of the plant, just moments ago now become part of myself. They enter first my bloodstream and then my brain, where they produce a relaxing state of mind, exalted spiritual awareness, and a heightened consciousness. This is the cannabis plant “taking possession” of me. What used to be the plant is now a part of myself, part of my personality, and she enters my thoughts and helps guiding me – until my body metabolizes the psychoactive compounds and she leaves me again.

Now contrast that to, say, fruit wine. Don’t get me wrong, I enjoy a glass of good wine occasionally, and we make a batch of berry wine each year. But the process is decidedly different. What enters your body and produces the mind-altering effects is not the plant itself, at least not directly. It’s the metabolic waste products of the yeast that eats and digests the sugar in the solution, and excretes alcohol. What’s entering your blood and brain is not a compound that used to be a plant seconds ago, but the metabolic waste product of a certain species of fungus. Mold excrement, so to say.

This is why alcohol, especially at higher dosages, produces pronouncedly different effects: it impairs your senses, simplifies your thoughts and narrows your consciousness and scope of awareness. This is also why the next morning feels so horrible.

If you want to know what it feels like if the fruit itself becomes part of you, simply eat the fruit directly and you’ll know. But what holds for animals is also true for plants:10 Eat fruit soaked in chemicals and artificially inflated with nitrogen salts, and you’ll feel one way – but eat fresh, organic fruit grown in living soil by happy plants, and you’ll feel much like the plants that gifted you with their fruit.

So, now that we’ve established how everything in the world is connected to us (and vice versa), let’s return to the main question:

What happens when we die? Where do we go?

As a way to illustrate the process, let me give a simple example: One instance of a culture whose burial practices explain this concept in a way even young children can understand is the Tibetan practice of the “Sky Burial.” Dead bodies are placed on large stones at the top of mountains, where they are eaten by carrion birds and other scavengers. Monks sometimes observe the scenery while meditating with open eyes, contemplating death. Regardless of what Tibetan Buddhists believe happens to the dead person, what we can observe directly and without the need to believe in supernatural forces and worlds other than the one we’re in is the following: what used to be the person now becomes part of the birds that eat it, who carry the deceased within their own bodies, and they help spread the deceased’s remains far and wide, to reintegrate them into the larger whole, the Community of Life, as fast and efficiently as possible.

This shows again that, as stated above, the particles that made up your body will slowly begin to dissolve into the environment, and tiny parts of your consciousness, your mind, will fuse with it and its many constituents. This process is infinitely complex, and I will give only a handful of examples to illustrate its general Nature.

You will become the myriad creatures that feed on your corpse.

As soon as you’re in the ground,11 thousands, no, millions of tiny creatures will begin feasting on you. Most of them will be microorganisms, constituting the lowest trophic level. Others will be slightly larger.

If you were healthy, they will be healthy, which also means that if you were happy, they will be happy. But if your body was full of microplastics and carcinogens, their bodies will be poisoned by those substances as well, and this will affect their mental state and their personalities.

And thus begins your journey throughout the Community of Life – or, let’s say, thus continues your journey. Everything that makes up your body, at any time, used to be part of someone else, some plant, animal, fungus, or any other entity, and now you return to them – now you become part of them. The fire of life that used to burn in you now feeds their fire.

Now that you have started dissolving into the broader world, it is your time to become food. Countless tiny yous will fuse with the organisms that ingest them, and you will live on within them. You will experience the world through their senses, and merge with their personalities.

You will become the myriad creatures that feed on the creatures that feed on your corpse.

The first creatures that you’ll become a part of are usually smaller beings, some so small that we can barely see them, others slightly larger, like the ubiquitous maggots and other carrion insects. Those beings feed on lower trophic levels in the food web, and they now carry within them something that used to be you, and a part of you lives on in them. They will be preyed upon by others who inhabit higher trophic levels, and you will start accumulating in those animals as well. The maggot is eaten by the bug, who is eaten by the centipede, who is eaten by the bird, who is eaten by the snake, who is eaten by the leopard. You will be the maggot, the bug, the centipede, the bird, the snake, and the feline.

You will see the world through their eyes, sense the world through their senses.

You will return to your community.

Not only will you become a part of the larger Community of Life, you will also return to your human community, and touch the lives of everyone that was dear to you again. As the droppings of the Tibetan raptors fall onto the fields that people cultivate, the crops will soak up the nutrients that used to be part of their loved one’s body, and whose mind is still bound up with that matter. Once people harvest and eat those crops, their deceased relative enters their bodies again, and lives on within them for some time, until it is time to continue the never-ending journey.

One way or another, you will feed the crops and animals that feed the people of your community, and you will once again become part of it. Some parts of you were always a part of it, and some will always be.

Sometimes this process is initiated directly: the most common form of ritualistic cannibalism practiced historically by some indigenous cultures is endocannibalism, which means that the remains of deceased loved ones and friends are ingested, often accompanied by elaborate rituals, so that the deceased may become, quite literally, a part of their friends and families – that they might live on in the bodies of the members of their community. This form of “cannibalism” is a relatively harmless spiritual belief that manifests itself in many different ways; one of the better-known examples is the Yanomami tradition to mix the ashes of their cremated dead into a kind of fermented banana soup they then eat.12

You will become the clouds.

Most constituents that make up your body and mind are water molecules, and those water molecules will be released back into the world soon after you die. This process usually starts even before death, as dying people usually refuse to drink water shortly before they pass.

Some of that water will seep into the soil to directly feed the plants, and some of it will evaporate, and travel on air currents until it finds itself surrounded by an ever-more dense aggregation of water vapor, that in time becomes so dense that you, together with many other water molecules, condense around a solid nucleus that falls back towards the earth as soon as it gets heavy enough. You will fall onto the land and into the sea, and parts of you will evaporate again soon after.

Within no time, some parts of you will have traversed all continents, and in a matter of months, you have spread over the entire world.

“Welcome back,” the other water molecules say to you.

You will become the forests.

As the rain that contains you falls onto the land, it is being soaked up by thirsty plants and pools in puddles that thirsty animals can drink from. You water the forest and its inhabitants. At the same time – assuming you’ve been buried – you will have started entering the lowest trophic levels of the food web again, as your body feeds the myriad creatures that live in the soil and transform organic matter. As we’ve seen before, you will become the maggots, nematodes, larvae, worms, bugs and microorganisms that live on and in the soil, and after progressing through their tiny bodies and becoming them, you’ll become a part of the soil.

The creatures that feed on your corpse will take up whatever building blocks their bodies require, and excrete the rest as nutrient-rich fertilizer for plants to utilize. This manure still consists of the same matter that used to be you not too long ago, and now that it’s on and in the ground, processed into bioavailable forms of nutrients – you will become humus. Hungry trees stretch out their roots and rejoice when they tap into the fertile soil that is you, and you will travel up through their roots and into their bodies, into the tips of their shoots, to become their leaves. You will become the trees, and as they shed leaves that decompose on the forest floor before being taken up by other trees nearby, you will infuse the entire forest shortly after.

You will become the ocean.

Ultimately, many of the tiny entities that once made up your body at one point will find themselves in the ocean. As terrestrial mammals, we often forget that the thin layer that comprises the biosphere, what we call “the world,” predominantly consists of water. Over time, much of what used to be you, the heavier molecules and compounds that are not soluble in water, will eventually settle on the bottom of the ocean. Once there, you will sleep, long and deep, as a part of the gigantic planetary conscious, until the creation of a new world starts. Over hundreds of millions of years, geological processes lift tectonic plates, and with a bit of luck, many of the entities that used to constitute your human form will slowly start waking up, awoken from their slumber by the warming rays of our Mother Star. And thus, a new world is born, one so radically different from the last time we were wide awake that past worlds are like a distant memory. The planet itself is still the same, as it always was, but the configuration has changed dramatically over the eons you were asleep.

This is your home, and it always was and always will be.

I hope that the above ideas don’t offend anybody, and I want to stress once again that I don’t think that what I presented here is some sort of absolute truth – it is merely my own interpretation, the one that makes the most sense to me and that I find it easiest to believe in.

I am not a Buddhist (there are many teachings I strongly disagree with, as with all other large, institutionalized religions that traverse space and expand beyond the lands from which they sprung13), but I definitely think that Buddhists are onto something with their concept of reincarnation. It even seems to me that Buddhist reincarnation is like a simplified explanation of the process I have attempted to describe here, with a few minor misunderstandings and inaccuracies (such as that there is an order with “higher” and “lower” beings – which is the same anthropocentric nonsense expressed in Aristotle’s scala naturae – and that in Theravada Buddhism men are higher on this scale than women).

But I don’t wish to provide an extensive critique of Buddhism here (which I might nonetheless attempt in a later essay). I merely want to point out the similarities.

The main difference is that while (especially Theravada) Buddhism seeks to escape Saṃsāra – the constant cycle of life and death – and attain Nirvāṇa, I celebrate being a part of it as the Highest Good: the path is the goal. I strongly reject the desire to break loose from the wondrous, endless cycles of Nature. Being a part of the Cycle of Life is the objective, in my opinion, and its infinitude is part of its beauty and appeal.

The realizations I’ve tried to put into words here helped me immensely, both in terms of processing other people’s deaths and in contemplating and accepting my own mortality. This cosmology leads me respect and revere all life as if it would be my own, because in a way it is – we’re ultimately all the same.

Our ancestors and deceased loved ones are everywhere; they always surround us, traverse and influence us, and thus the entire landscape is sacred, and each being and entity in it is holy.

The beliefs I subscribe to don’t require weighty tomes or complex theories to describe them – to arrive at the conclusions I presented here, simple observation is enough. This is what’s actually happening, and you can witness the process each time you stumble over a decaying body. I used some scientific language, spoke of atoms and molecules, but those are just the words we’ve grown accustomed to. You don’t need a microscope to see how a dead body is fed back into the greater whole through thousands of little beings, or to observe how what was you becomes someone else.

Moreover, there is no need to imagine almighty sky gods, heavenly realms or parallel universes. If you want to know how the world works, it is enough to carefully look at it, and experience it with an open heart.

As the Native American saying goes, “if you take the Christian bible and put it out in the wind and the rain, soon the paper on which the words are printed will disintegrate and the words will be gone. Our bible is the wind and the rain.”

My religion, if you want to call it that, is the same as that of the mountains, the rivers, the trees and the birds – because we are the same.

I was once sarcastically asked if I’d be ready to be torn apart by a wild animal, since I openly advocate a return to a simpler way of life in balance with one’s environment.14 I retorted that, while no known predator exclusively or even regularly preys on humans, it would be the greatest honor for me to be devoured by a tiger. I know that, with the Sixth Mass Extinction unfolding, chances are rather slim, but what matters here is the willingness. I’m okay with becoming prey. Ultimately, we will all become food anyway.

Furthermore, my sense of self-worth is not being diminished if I’m not “on top of the food chain” at all times. Once I’m too old to run or climb trees, I’d become a burden for my community, so it would better for everyone if my life ended swiftly and painlessly15 between the strong jaws of a tiger.

I would become the tiger, I would live on in her, and the fire of life that burned within me would help keep her fire burning. To me, this would be the highest honor: there is nothing more beautiful than being part of this never-ending exchange.

Indigenous peoples have known all this since the beginning. It is us, the members of the dominant culture, who forgot it, who distracted ourselves with stories of pie in the sky and fantasies of escaping this world. As Chief Seattle reminded us:

The Earth does not belong to us; we belong to the Earth. All things are connected, like the blood that unites one family. Whatever befalls the Earth, befalls the children of the Earth. We do not weave the web of life; we are only a strand of it. Whatever we do to the web, we do to ourselves.

I write stuff like the above in my free time, when I’m not tending the piece of land we’re rewilding here at Feun Foo. As a subsistence farmer by profession I don’t have a regular income, so if you have a few bucks to spare please consider supporting my work with a small donation:

If you want to support our project on a regular basis, you can become a Patron for as little as $1 per month - cheaper than a paid subscription!

With the possible exception of Diogenes of Sinope, one of the founders of Cynicism.

This is true for many other teachings of “Science” as well – it is utterly irresponsible to teach little children that the sun will expand and devour the Earth in eight billion years, for instance. Knowing this does not make anyone’s lives better even the slightest bit, and leads to the same nihilistic tendencies I’ve just outlined.

There is nothing “New Age” about psychedelics, though. Those plants have been used for countless millennia by various indigenous cultures to facilitate communication with the spirit world and for healing rituals.

If you would attempt to divide a coin, you’d just end up with two slightly thinner coins that both still have two sides.

This does not mean that one is better than the other, or more capable, or more complex, or more “evolved.” But larger minds tend to have larger memories and a larger processing capability, for instance.

“What defines the mountain? Who defines where the mountain starts and where the valley begins,” you might interject, but that is kind of the point here. We are not skin-encapsulated egos, and the horse is not a horse. With mountains and rivers the teaching is just more obvious than with animals or plants.

As a recent study found: “Thoroughly revised estimates show that the typical adult human body consists of about 30 trillion human cells and about 38 trillion bacteria.” The total bacterial weight is about 0.2-0.3 kg.

If I remember it right, I read this metaphor in one of Stephen Harrod Buhner’s books, but I don’t remember which one.

We breathe out carbon dioxide, which literally becomes part of a plant’s body, and the plants breathe out oxygen, which in turn becomes part of our bodies. This exchange is a constant reinforcement of our spiritual and material conectedness to the ecosystem we inhabit.

…and fungi, people always forget fungi!

Assuming that’s what your culture does with dead bodies, and, assuming further, you’re not a US-American whose corpse is stuffed with formaldehyde and other embalming chemicals, and thus degenerates into a toxic sludge that will take much longer until it enters the Cycle of Life again.

Cats seem to understand this principle as well: when their kittens die, they will express grief and consequently eat the corpse(s) of their young, so that their babies become part of themselves again.

Such as the fact that all major religions can be used to justify dominance hierarchies – which is why they are major religions. Any belief that delegitimizes dominance hierarchies is eventually exterminated by the dominant culture, and replaced with a teaching that can be interpreted in a way that pleases the rulers and reasserts their status in the hierarchy.

Presumably this way of life was characterized by constant danger and misery – at least that’s what the dominant culture teaches us.

I’d like to share the following passage from Christopher Ryan’s book ‘Civilized to Death’:

“Along with its indifference and occasional cruelty, nature has surprisingly compassionate qualities as well. One example is the euphoria-inducing compounds called endorphins that are released in mammals precisely when they’re needed most. For obvious reasons, there are few firsthand accounts from people who have lived to describe the experience of being in the death grip of a predator, but the famous British explorer David Livingstone gave an unusually articulate account of having been attacked by a lion on one of his African expeditions:

‘I heard a shout. Starting and looking half round, I saw the lion just in the act of springing upon me. I was on a little height; he caught my shoulder as he sprang and we both came to the ground below together. Growling horribly close to my ear, he shook me as a terrier does a rat. The shock produced a stupor similar to that which seems to be felt by a mouse after the first shake of a cat. It caused a sort of dreaminess in which there was no sense of pain nor feeling of terror, though quite conscious of all that was happening.… The peculiar state is probably produced in all animals killed by carnivora; and if so, is a merciful provision by our benevolent Creator for lessening the pain of death.’”

There is no need to fear.

This was another beautifully written piece my friend, up there with ghosts without a shrine for me. I will make a longer comment shortly with some of my own thoughts on the subject. I also greatly enjoyed your other post from the other day!

This was very perspective shifting for me and yet it did feel like common sense, as you said.