In Defense of Delayed-Return Hunter-Gatherers (I. of III.)

Addressing an unmerited bias in Anarcho-Primitivist circles --- Part One: Are Shifting Cultivators Hunter-Gatherers? --- [Estimated reading time: 30 min.]

A few weeks back, I was interviewed by Artxmis for the Uncivilized Podcast, and we had a delightful conversation in which I took, with great excitement, the role of the “apologist for delayed-return hunter-gatherer societies.” The entire conversation lasted over two hours, yet much was left unsaid – it is, after all, one of my absolute favorite topics, and if you’ve ever been a guest or volunteer at our permaculture project, you’ll know that I could easily talk about the issue for a few hours every day – day after day after day. In an effort to dive a bit deeper into the details, I’ve decided to elaborate on a few things I touched on in the conversation with Artxmis in writing.

It is, indeed, somewhat tragic that delayed-return hunter-gatherers in general get such a bad rap in most primitivist circles, which tend to uphold (almost exclusively) immediate-return hunter-gatherers as their “ideal societies.” Cultures such as the !Kung, the Baka, the Hadza, the Jarawa, the Mani, the Penan, the Pirahã, and many others still exist today, despite the constant onslaught of ‘progress’ and ‘development’ threatening their societies. Those people are seen as somewhat “exemplary” foragers, since they do not produce substantial surplus, don’t store food for longer periods of time, move around more often, and don’t work harder now for a delayed calorific return a few weeks or months later. Among primitivists, it is widely believed that only immediate-return societies that meticulously abide by the aforementioned guidelines and rules can, as a society, stay truly egalitarian and anarchist, and are thus sustainable in the long term. Every transgression, according to established primitivist dogma, puts you down the path towards (eventual) disaster.

The ‘classical’ primitivist stance was aptly summarized by my friend Jessica Carew Kraft in the introduction of her highly recommendable new book Why we need to be Wild – One Woman's Quest for Ancient Human Answers to 21st Century Problems:

“By spending time with anthropologists, I learned that there is a big difference between hunter-gatherers who share food equally among their group versus the more recent, ‘complex’ hunter-gatherers who hoard food sources to accumulate power and prestige or who begin controlling the production of resources through planting crops.”

This statement seems to be pretty much common sense among most primitivists – even among those with a background in anthropology. Delayed-return societies are seen as somewhere between ‘the good life’ and civilization, a step removed from the ‘pure’ state of immediate-return foraging. As Jessica points out, they are thought to “hoard food,” “accumulate power and prestige,” and “control the production of resources.” This sounds almost like the proto-colonizer’s mindset – certainly not like anarchists! – and it seems unlikely that anything but full-blown chiefdoms (with a strong leader, dominance hierarchies, warrior cults and slavery) and, in time, city states will be the result of this seemingly inconspicuous switch from ‘immediate-’ to ‘delayed-return.’

But this characterization is not only a gross oversimplification, it is often plain wrong. How many times have I heard people dismiss all delayed-return foragers by talking about them like they’ve already gone off the right track, like they’re somehow in the process (or in danger) of disconnecting from their landbase and rising to the “next level of complexity” – first hamlets, then villages, then towns – on a (mostly imaginary) ladder towards civilization.1

Yet, in my opinion, this flat-out dismissal is undeserved. Delayed-return societies can be excellent examples of inspiring human cultures living within the limits of their ecosystems, without damaging or degrading them in the long-term. Many times, lands “managed” (or, better, tended) in this fashion by indigenous societies were found to be even more diverse and productive than habitats without human presence, since we humans can (under the right circumstances) act as a keystone species, nudging the ecosystem towards more efficiency, abundance and diversity. We are (undeniably) good at creating disturbances in the ecology, and those disturbances can, in moderation, be very beneficial to the ecosystems we inhabit.

Forest habitats, for instance, start stagnating as they approach maturity, and at a certain point they reach a climax state, in which not much happens anymore and carbon sequestration levels and biodiversity peak. Most ecosystems need slight disturbances to stay healthy, and they benefit greatly from the rejuvenating effects those disruptions have as a consequence. In the case of tropical forests, the main focus area of this essay series, disturbances can be typhoons or other storms, herds of large herbivores such as elephants, or small groups of delayed-return cultures occasionally clearing a patch of land to reset ecological succession.

Naturally occurring wildfires are less common in the tropics, and fire is always a double-edged sword. But wielded by wise and responsible cultures, even the seemingly destructive practice of ‘slash-and-burn’ definitely doesn’t mean those cultures destroy the land they inhabit, or even that they inevitably become more hierarchical in the process. But I’m getting ahead of myself. My point is that anarcho-primitivists, generally speaking, know very little about the realities of shifting cultivation and other indigenous horticultural techniques – and about the effects those subsistence strategies have on social organization. My aim with this essay series is to change that.

Furthermore, I think it likely that the image many primitivists have of delayed-return foragers is heavily influenced by some of the pre-colonial tribes of the North American Pacific Northwest. Many of those coastal cultures relied not mainly on plant cultivation, but on abundant annual salmon runs that supplied them with a storable surplus of their main staple food – dried fish – that fed them for the better part of the year.2 Those delayed-return societies had access to reliable and inexhaustible seasonal resources worth appropriating and defending, settled in greater densities around said resources, became increasingly socially stratified, and in some instances even had slavery as a part of their social structure – but they are in no way exemplars of delayed-return societies globally.

As anarchists, we of course strongly oppose slavery, but it is an error to think that all delayed-return societies, by default, become heavily stratified and divided into different castes – and nor should we too strongly condemn a culture that didn’t destroy its landbase. As I say in the interview, “if I would have lived there, I would have probably done exactly the same.” And who knows what social reforms or revolutions would have awaited those societies, had the colonizers’ diseases not cut their history short?

Social contracts are always under negotiation, always shifting, and rarely stay the same for any extended periods of time (industrial civilization being one of the main exceptions). Inequality begets discontent, and discontent is the seed from which revolutions grow. If you live in a highly hierarchical society and are dissatisfied with this arrangement, it is your duty to do whatever you can to change things – this is as true for traditional societies as it is for contemporary civilization.

But first, a few definitions and clarifications

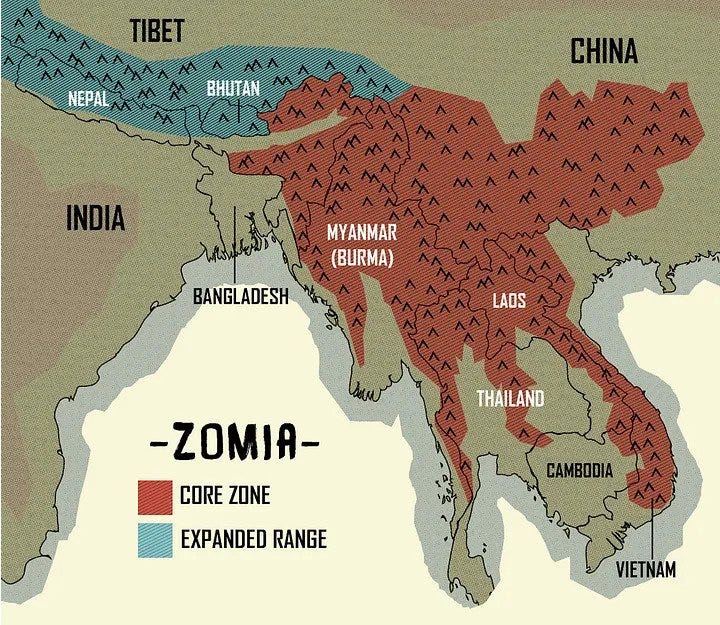

In the following, I will rely heavily on Anna Loewenhaupt Tsing’s brilliant 1993 ethnography of the Meratus Dayak inhabiting the mountains of Kalimantan, Indonesia – In the Realm of the Diamond Queen – from which I will quote extensively.3 I will draw parallels to other hill societies4 as often as possible, though, because relying on a single culture to make my point might invite criticism of making sweeping conclusions based on a limited (and thus biased) dataset. But, as James C. Scott says himself in the Introduction to his phenomenal 2009 opus The Art of Not Being Governed – An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia (another source that I will draw upon heavily), the many theories he presents in this book (such as that hill societies throughout Zomia5 can be categorized as ‘anarchist’ without doing them injustice), can be applied just as well to the various maritime cultures commonly called “Sea Nomads,” and other shifting cultivators throughout Southeast Asia. The Meratus Dayak that Anna Tsing describes are, in many ways, exemplary of local non-state societies in general, which is why I picked them as a case study.

I will try to draw parallels to South American horticulturalists whenever appropriate, but my main focus is on the (internationally underrepresented) delayed-return foragers of Southeast Asia.

The various, often highly stratified horticultural societies of the Pacific Islands are in many respects a bit of an outlier in this debate. Cultures like Native Hawai‘ians, Sāmoans, the Māori, the inhabitants of Rapa Nui and various highlanders in Papua New Guinea were historically more reliant on fixed-field plant cultivation and animal husbandry, and hence more sedentary – and, concomitantly, hierarchical. Including them in the following analysis would surely exceed the scope of this essay series (which focuses on potential “anarchist” societies), and a discussion of their cultures and subsistence modes would merit their own analysis. But for the purpose of integrity I will reference them whenever necessary.

Furthermore, when talking about the hill cultures of Zomia, I will – just as James C. Scott does – mostly refer to the period before the Second World War, because afterwards the various governments in the area increasingly managed to forcibly settle down the formerly semi-nomadic hill cultures. As the state expanded its reach, built all-weather roads and bridges, and utilized more modern technology to incorporate even the hinterlands into the dominant, all-embracing and increasingly powerful realm of the nation state, the area’s ‘original anarchists’ were forced, often quite literally, to adapt or to die out. Ever since, most hill societies have been coerced to adopt some version of fixed-field farming, which robs them of an important prerequisite for their historic egalitarian tendency: the freedom to move away – but more on that later.

By far most hill people these days live in permanently settled villages and tend to their fields in which they grow corn as a cash crop (to be used as animal feed in factory farms), but often still practice traditional swiddening on smaller plots, where they grow rice and other crops for personal consumption and local markets.

To avoid any confusion, let me state, in the briefest possible form, my definition of the terms ‘agriculture,’ ‘horticulture,’ ‘swiddening/shifting cultivation/slash-and-burn,’ ‘permaculture,’ and ‘totalitarian agriculture.’

The term ‘agriculture’ derives from the Latin ager, meaning ‘field,’ whereas ‘horticulture,’ on the other hand, comes from hortus, meaning ‘garden.’ The difference between the two is obviously one in scale (fields tend to be bigger than gardens), possibly one in density (fields tend to be planted more densely, whereas in gardens one often utilizes the ‘edge effect’), and definitely one in diversity. Following this distinction, indigenous societies practice(d) horticulture, not agriculture – agriculture is the main subsistence mode of cities and civilizations.

‘Swiddening’ is the indigenous horticultural technique of clearing of small patches of rainforest (swiddens), carefully burning the vegetation, and using the resulting opening in the canopy (and the boost in fertility provided by ashes and charcoal left over from the burning process) to plant a few crops, after which the land is allowed to rewild – albeit with a bit of human interference. I will use the terms ‘swiddening,’ ‘shifting cultivation’ and ‘slash-and-burn’6 interchangeably for traditional horticultural practices of various indigenous societies, at least if not otherwise denoted.

‘Permaculture’ (short for ‘permanent agriculture’7) is, according to Bill Mollison’s 1988 book Permaculture – A Designer’s Manual, “the conscious design and maintenance of agriculturally productive ecosystems which have the diversity, stability, and resilience of natural ecosystems” – and extends to include the human cultures that form around such regenerative ways of food cultivation.

‘Totalitarian Agriculture’ is a term coined by Daniel Quinn, and is used by him to set apart indigenous “agriculture” (which I prefer to call horticulture) and the kind of agriculture the “Takers” – the settlers, colonizers, and their civilizations – practiced. Totalitarian agriculture includes the early grain agriculture that fed the first cities, and stretches until today’s industrial agriculture (and beyond). You know that you practice (totalitarian) agriculture if you a) take a diverse ecosystem and turn it into an ecological desert, b) see this as your God-given right and yourself as ‘in charge’ of the environment, c) grow all (or almost all) of the food you eat in this way, and d) don’t want to share with any other living being and thus strive to deny access to, drive off or outright exterminate possible competitors. Bonus points if you keep the food “under lock and key” in a centralized, guarded granary, special bonus points if you’re able to feed a parasitic class of elites with your surplus.

But now to the first of our three main questions:

Are shifting cultivators hunter-gatherers?

This is another pressing question that needs to be answered before diving into the discussion of whether delayed-return foragers, especially the hill societies of Southeast Asia, are really “one step down the road towards civilization”:

Can they actually be called ‘hunter-gatherers’?

Well, for starters, they do hunt and gather pretty much daily, although that alone obviously doesn’t make one a hunter-gatherer. But hunting and gathering does not only contribute a reasonably large chunk of their daily nutritional intake, it is a really important aspect of their culture. South American delayed-return foragers/horticulturalists such as the Yanomami, the Achuar, the Waorani and the Kayapó are more often seen as “real hunter-gatherers,” because the men will go out hunting (almost every day in most cases), whereas the women tend to their gardens and gather jungle fruit and produce. Hill cultures, on the other hand, do tasks associated with plant cultivation together, often without a clear divide along gender lines, and thus seem more horticultural on the surface.

During our conversation, Artxmis asked me where I would draw the line between hunter-gatherers and horticulturalists, and I responded that I don’t think this is possible, necessary, or even helpful. Subsistence strategies – and the social organization they enable – are best understood as a spectrum: non-cultivating immediate-return hunter-gatherers like the Mlabri, the Mani, the Senoi and the Penan are on one end, the (previously mentioned) Amazonian delayed-return foragers and Southeast Asian hill societies like the Lisu, the Lahu, the Akha, the Palaung, the Kenyah, and the Dayak somewhere in the middle, and more stratified societies that often rely on a single subsistence strategy, many times the cultivation of a certain staple crop (or the herding of a particular species of animal), for most of their calories on the other end. Societies on the more hierarchical end of the spectrum include many Pacific Northwestern cultures that harvested hyperabundant salmon runs, and most Pacific Islanders. In between the hierarchical indigenous cultures and those in the center of the spectrum are some of the firmly horticultural hill societies inhabiting the lower mountains of Zomia, like the Shan, the Hmong, the Yao, the Wa, the Kachin or the Karen.8

In terms of social organization, those cultures are definitely a bit closer to actual farmers than they are to hunter-gatherers, although both hunting and gathering still play an important role for them. Historically, the latter societies (and a few others) were more open towards hierarchical arrangements than other hill societies, in some instances even forming small ‘kingdoms’ and miniature ‘states’ (which usually fell apart as fast as they formed). Their members were occasionally enslaved by slave raiders from the ‘civilized’ lowlands, but they also went on their own slave raids to capture members of “weaker” (i.e. less inclined towards violence) hill societies that were deeper (and higher up) in the mountains, such as the Akha, the Lisu and the Palaung.9 Those societies inhabiting the lower foothills were also in more direct contact with the valley states, and thus were able to profit from the trade in hill- and forest products, which were exchanged for metal tools and ornaments, salt, cloth, guns and the like. Those (highly sought-after) items were often resold at much higher prices to people living higher up in the mountains, who were thus a few steps further removed from the reach of civilization (Scott, 2009).

Hence, the higher you ascended into the hills, the closer to the ‘hunter-gatherer archetype’ – and thus the more egalitarian – were the cultures you encountered. Movement between those cultures was relatively free, and when your current community became too authoritarian, you could always “vote with your feet” and join other communities further up the mountainsides (Scott, 2009).

As I always say, nothing is black and white – and this is most certainly true for human cultures. Trying to classify them into neat binary categories of ‘immediate-return vs delayed-return’ or ‘hunter-gatherer vs horticulturalist’ is usually an unfruitful exercise and, more often than not, misses the point entirely. Again, it is important to consider that reality looks more like a spectrum, with lowland civilizations on one (very) extreme end, and immediate-return hunter-gatherers like the Mani and the Mlabri on the other one.10 Hill societies and other horticulturalists generally fall somewhere in the middle, depending on the altitude of their swiddens (and thus their degree of vicinity to agricultural civilizations) and/or the frequency of their migrations.

As we will see again and again in the following paragraphs, the lifestyle swiddening allows is (apart from the initial clearing of the land) very similar to what we understand as foraging and wildtending.11

To illustrate this point, one of my favorite examples is a passage12 from Anna Tsing’s ethnography that I’m afraid I will have to quote at great length, since no summary could ever do it justice. After citing a government report that showed that there were supposedly “only twenty-three commercially valuable trees per hectare in this forest,” Tsing goes on to explain not only how the Meratus Dayak interact with their environment, but also how they view ownership, which is relevant to the discussion of whether Southeast Asian shifting cultivators are anarchists or not (which I will elaborate on in the last Part of this series).

“It is hard to imagine any hectare of forest—from the youngest regrowing brush to the oldest stands—in which Meratus would find only twenty-three useful plants. (The obvious exception might be areas left by the timber companies: steep hillsides choked with sliding stumps amidst thick mud; rolling red earth bedecked only with unanchored balaran hirang vines.) Meratus use forest resources in every aspect of daily life. They appreciate the diversity of the forest and learn its variations. Their resource use leads to forms of ecological knowledge that are much more locally detailed than those of the state or the logging companies. In contrast to the forest official’s assumption that all regeneration outside of tree plantations can be lumped into an uncontrolled category glossed as ‘natural,’ Meratus create a variety of relationships to forest plants. Indeed, it is difficult to draw a line between ‘wild’ and ‘domestic’ in Meratus forests, because of the variety of ways in which people interact with plants and plant communities. When swiddens are cleared, some useful trees are spared and protected. These trees remain as forest dominants as the field regrows into forest. Some trees are planted in swiddens or grow from seeds casually deposited in household garbage. Some sprout from the stumps left in swiddens. Others take advantage of the light-gap created by swiddens, flourishing in old swiddens without human assistance. Further, even without clearing fields, Meratus influence the composition of the forest: Some trees are cleared of vines or surrounding brush to encourage their growth; some plants are harvested in ways that allow regrowth. As people walk through the forest, they continually check on the status of the plants they have planted, encouraged, or merely encountered before. It is through these varied interactions with plants that Meratus come to appreciate the diversity of the forest.

Consider fruit, for example. Meratus enjoy dozens of varieties of seasonal forest fruits. Some, like sweet-sour wild mangos (hambawang), are thought of as trail-side snacks rarely worth carrying home; others, like the strong-smelling, custard-like durian and the sweet, sticky tarap (Artocarpus elastica), can be major food sources. Each of these examples has a contrasting niche in Meratus agroforestry. Durian trees are among the most valuable of claimed trees. They are planted in old swiddens; they would certainly be saved in swidden-making; they also sprout in garbage drops and in the forest without human assistance. Ripe, fallen fruit belongs to the finder; in durian season, teenagers set out excitedly before dawn to collect the fruit that fell the night before. Only claimants, however, may climb the trees to harvest and distribute unripe fruits. In contrast, tarap trees are common, and anyone may harvest them; but sometimes a tarap tree will be saved in a swidden—and thus claimed. Hambawang trees are merely remembered in relation to their location; they become a goal for hikers anticipating refreshment.

Even closely related species can merit quite different treatment. Included among the mangos, for example, are the odiferous binjai (Magnifera caesia) and the tiny rawa-rawa (M. microphilla?), both of which can be planted, encouraged, or merely encountered in the forest, as well as the stringy, juicy kwini, which grows only as a cultivate. Durian relatives include the spiky red lahung, which can be planted or, if encountered, encouraged; the orange-fleshed pampakin, a cultivate; and the miniature lahung burung, never planted but appreciated as a trail-side snack. Other Artocarpus species (i.e., like tarap) include the large-fruited cultivate (or sometimes spontaneous) tawadak (A. integer), as well as the self-seeding forest trees kulidang and binturung. The latter two trees are plentiful enough in the forest to make their fruits one option for a temporary staple when rice supplies run out. In contrast, nangka, the jackfruit commonly planted in Banjar [an ethnic, agricultural Muslim culture inhabiting the valleys below the Dayak lands] houseyards, is quite rare in the Meratus area, because the giant fruits require continual attention and protection. Except in some foothill areas, Meratus rarely create ‘domesticated’ orchards; Meratus fruit trees must thrive—or, at least, survive—as part of the forest. But, in a sense, the forest is an orchard. Some forest fruits are valued in ways that do not involve human consumption. Young men bird-lime the branches of kariwaya strangling figs to catch the birds attracted to the fruit. Hunters haunt fruiting luak trees, whose figs hang in clusters from the tree trunks, waiting for the deer that enjoy this fruit. Fish swim into traps baited with kasai (Pometia pinnata) fruit. Migrating wild pigs follow the fruitings of sinsilin oaks and damar dipterocarps; and men, with their dogs and spears, follow the pigs.

These trees provide more than fruit. Damar, for example, is a source of bark for construction and resin for lighting. Damar trees can also serve as supports for the nests of migrating wild honeybees, indu wanyi. The bees fix their combs under the branches, choosing sites exposed to light. This does not hurt the tree. In fact, Meratus encourage the tree’s growth by encouraging the bees’ comb-building: They clean off vines and clear underbrush. They say the bees come back year after year to their favored sites. From these combs, Meratus harvest honey, larvae, and wax. Only claimants can harvest and distribute the honey. Honey trees are claimed by finding and tending them. They are saved in swidden-making; sometimes appropriate trees are also planted. Some men claim as many as fifty productive honey trees.

Honey trees include many of the forest’s big trees. Besides damar, people consider mangaris, binuang, salang'ai, mampiring, alaran, tampuruyung, pulayi, luak, jalamu, hara wilas, kupang, mijuluang, kasai tikus, jalanut, simuan, and anglai potentially good honey trees. Even without introducing Latin names, this list suggests Meratus appreciation of forest diversity. It seems worth noting that included in this list are species cut for plywood export (for example, Shorea acuminatissima [damar hirang] and Octomeles sumatrana [binuang]), species cut for construction wood, and species of no commercial value which may or may not survive the logging process. The contrast between the local detail of Meratus practice and the revenue-focused mathematics of national forestry interests should be clear.

In staging this contrast, it would be a mistake to remain in the loggers’ discourse by considering only trees; there are many other useful plants in the forest. Meratus use bamboo, palm, tubers, herbs, and fungi, among many other plants. Most Meratus know where to find numerous kinds. For example, more than half a dozen species of bamboo are used variously for cooking utensils, firewood, food, basketry, house construction, musical instruments, ritual decorations, and carrying water. Finding the appropriate species is facilitated by the fact that many bamboos remain a rather stable element of the forest. Generally, bamboos are not killed even by swidden construction; they grow back even more densely as the forest returns. (In one western foothill area, Meratus plant bamboo in old swiddens to prevent the spread of Imperata grasslands and to hold claims on future swidden plots. This type of bamboo is also a cash crop.) As people traverse the forests grown from old forest clearings, old forest harvestings, and old forest tendings, they become increasingly familiar with the species composition of particular forest areas. Conversely, their knowledge allows them to use an area’s resources more intensively.

Everyday traversings, along with the intimate knowledge they create, help establish and reestablish claims on a place and its resources. A person invokes a claim to fruit trees by checking to see when they are producing fruit; if the fruit ripens without being visited, someone else is free to take it. Only a few forest resources (for example, rattan, honey trees) provoke competition; for most forest products, there is scope for the overlapping, nonexclusive claims of neighbors and kin whose forest paths cross each other. In claims of familiarity, knowledge and use of the forest are mutually implicated. When a person moves away from an area with no intention to return, she might say that she has ‘forgotten’ her trees there.” (Emphasis added, Tsing, 1993)

I invite you to decide for yourself if this sounds more like the lifestyle a farmer would lead – or more like that of a hunter-gatherer.

To me, it seems self-evident that shifting cultivators are (or, in most cases, were) simply hunter-gatherers who cultivate(d) some of their food, without degrading their environment or diminishing its natural resource base in the long term.

But, concerning delayed-return foragers of Southeast Asia, another aspect that needs to be addressed in more detail is the fact that hill cultures (and other nonstate peoples in the region) have undergone drastic changes in the last few decades, changes that have grossly distorted their public image. The pictures of elaborate dresses, necks lengthened with metal rings,13 and endless rows of beads and metal ornaments that come to mind when hearing the term “hill tribe” are a rather recent phenomenon and largely a product of the tourism industry and misguided efforts to “promote cultural diversity.” In other words, this approach is based on a focus on the purely superficial aspects of a culture – clothing, jewelry, music – to distract us from deeper-lying beliefs, traditions and customs that might be threatening to state hegemony and hierarchy.

This, in turn, has resulted in a concerted effort by Thai academics, government officials and the media to focus obsessively on those aspects that can be monetized (through ‘cultural tourism,’ i.e. human zoos), and to conceal and ignore those that would be detrimental to the state’s goals (namely a shared history characterized by insubordination and rebellion, and a culture based on autonomy and egalitarianism).

Yes, some contemporary hill cultures have excessively delicate ornaments decorating their clothes, which make them look a lot more like civilized people than like hunter-gatherers – but they don’t wear those outfits when they work in the fields, trek through the forest, fetch water or visit friends. Many times, those ‘traditional costumes’ are most frequently put on as a show for tourists, and have traditionally only been used for ritual purposes (akin to the ‘Sunday clothes’ in Western culture). Furthermore, the festive dresses of the past were undoubtedly decorated with some elaborate metal ornaments, but not to the extent that is common today.

Access to cloth, beads and metal increased manifold as hill societies were settled down and incorporated into the market economy. One of the things that happened as more families gained access to more regular wages and thus a bit of disposable income was (apart from an uptick in alcoholism) an upscaling of festive dresses, which had always been a means of representing status (most importantly age and marital status) and expressing beauty. This phenomenon has been observed among a wide range of societies, from various Native American cultures to the (immediate-return) !Kung of the Kalahari. One of the first things culturally acclimatizing foragers trade for (or spend newly-earned money on) are ornaments, accessories and other body decorations – often connected to status and beauty.14

Similar to the six-plumed birds of paradise we marvel at in David Attenborough’s documentary Our Planet, the resulting positive feedback loop of intensified selection for beauty (biological for the birds, cultural and economic for the humans) led to the extravagantly dressed hill people we now see adorning the covers of travel magazines. Pair this with the current Thai culture’s obsession to exaggerate the elaborateness of traditional costumes and dresses (for reasons of self-aggrandizement), and everyone thinks the “hill tribes” are those with the funny clothes. (Colonialist) mission accomplished!

But what this really means is, again, that things changed drastically once state power and influence became inescapable. As any anarchist knows, governments exist not for the benefit of their subjects, but first and foremost to secure and expand their own power, and the eternal job of the government is to increase its power and control over its subjects. This started with region-wide efforts to settle down mobile populations of swiddeners,15 which led them to grow cash crops, which in turn made them dependent on money, which then led them to abandon (and ultimately forget) many of their local techniques, traditions, customs, methods and beliefs. Gradually, they became more like the agriculturalists in the valleys.

A shift in subsistence mode is inevitably followed by a massive cultural shift.

To the onlooker, it might seem that shifting cultivation and agriculture are not that different, in theory or practice, but they are worlds apart. So how exactly does shifting cultivation look like in practice, and how destructive is it really?

The Truth About Slash-and-Burn - Read the next Part here!

I write stuff like the above in my free time, when I’m not tending the piece of land we’re rewilding here at Feun Foo. As a subsistence farmer by profession I don’t have a regular income, so if you have a few bucks to spare please consider supporting my work with a small donation:

If you want to support our project on a regular basis, you can become a Patron for as little as $1 per month - cheaper than a paid subscription!

This is one thing the notorious two David’s got right in their otherwise often misleading 2021 book The Dawn of Everything. We primitivists should know better than to fall for this self-serving lie civilization tells about its inevitability. There is no clearly defined “ladder” and making it to the next “highest” rung doesn’t mean you’re only going to push forwards. There is no shortage of societies that once practiced agriculture (or horticulture) and then went back to foraging in the anthropological record.

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that “[t]hose cultures relied not on plant cultivation, but on abundant annual salmon runs […],” although they also practiced horticulture – thanks to Matthew for pointing it out! My knowledge of hunter-gatherer cultures outside the climate zone I inhabit is patchy, and I’m always glad to lean more. As it turns out, Pacific Northwesterners did cultivate plants, and I’ve added Keeping It Living: Traditions of Plant Use and Cultivation on the Northwest Coast of North America to my (ever-growing) to-read list.

And I mean extensively – my apologies upfront. (But at least now you won’t have to read the entire book if you don’t have the time.)

Following Scott’s example, I use the terms ‘hill society’ and ‘hill culture’ instead of the more common ‘hilltribe,’ because the term tribe implies a shared lineage – whereas in reality, hill societies are genetically heterogenous groups comprised of a great variety of different people, including many refugees from valley civilizations. Speaking of a ‘tribe’ is thus misleading. (Of course, the same argument could be made about the Yanomami, but the agricultural phase of some of their ancestors probably lays deeper in the past.)

Zomia is the massive mountain range stretching from the foothills of the Himalayas, through Myanmar, Northern Thailand, Laos, all the way to Vietnam. Although the Cardamom Mountains in Cambodia and the Khao Soi Dao Mountain range in Eastern Thailand, in whose foothills I live, are not officially considered part of Zomia (and neither are the mountains further South on the Malay Peninsula and the Islands), the societies inhabiting these uplands were – at least historically – often very similar to the hill societies described by Scott.

Some scholars have, in an attempt to demarcate swiddening from the destructive practices of agriculturalist land-clearing, suggested the term ‘slash-and-char’ for the less invasive form practiced by indigenous societies. But since the importance of producing charcoal during the burning process varies greatly among various horticultural cultures, I’ll stick with ‘slash-and-burn.’

As I hope I made clear in the interview, I disapprove of the use of the term ‘agriculture’ in this context, because in my opinion agri-culture can’t be separated from its inherent anthropocentric bias. I prefer calling it “permanent horticulture” or simply a “permanent culture, including a permanent way of food cultivation.”

Among the previously listed hill societies, there are “both relatively hierarchical subgroups and relatively decentralized, egalitarian subgroups” (Scott, 2009). It is thus not easy to pin them down to any exact location on the spectrum.

Additionally, agricultural civilizations might be considered as somewhat of an extreme outlier, far off the natural spectrum of human social organization – the result of positive feedback loops such as the selection for traits that are in alignment with authoritarian social structures, such as obedience, docility and reduced potential for aggression among the broader populace, over several centuries and millennia.

This doesn’t mean that those societies could be categorized as slave-holding societies, though. Some groups occasionally captured slaves to sell to the lowlands, where slave labor was needed and slaves were highly priced. Without the market for slaves in the valley, there would have been no incentive to go on slave raids. Shifting cultivators have no use for slaves because their lifestyle is not very laborious, and what little “work” needs to be done is actually rather fun – especially since it’s always a group activity, and thus often accompanied by singing, joking, gossiping and shared meals and celebrations.

It bears mentioning that even classical examples of immediate-return societies sometimes “plant” seeds – among the !Kung, it has been observed that women on gathering trips sometimes throw a few berries on the ground and grind them into the soil with their heel as they walk (recounted by Helga Ingeborg Vierich, an anthropology PhD who lived with the !Kung, in personal correspondence). This is wildtending, and could even be considered a light version of (or precursor to) horticulture.

I define ‘wildtending’ as “the deliberate, careful and conscious modification of landscapes to increase productivity and/or diversity, without the explicit intention to domesticate either crops or animals.”

The passage in question spans three pages of the book, and is one of the most important sections of this ethnography. I urge you to read the entire book yourself, but if you don’t have the time, the quotes included in this essay series will suffice to give you a good overview without having to read the whole thing.

The groups commonly (and wrongly) known as “Longneck Karen” (they are actually a subgroup of Red Karen called Kayan) are a popular but dubious tourist attraction.

Whereas people of the dominant culture often instinctively assume that status is the weightier reason, if you asked the people in question, they’d assure you that beauty is their main concern (Kopenawa, 2013). Our cultural biases influence how we see others, and it often doesn’t make sense to project our own preferences and behaviors onto distinctly other cultures. What we can be sure of is that most early anthropologists saw hierarchies wherever they looked, but were so blinded by their own culture’s confirmation bias and superiority complex that they thought primitive societies were like obviously inferior miniature versions of their own – complete with patriarchy, monogamy, ranks and status, kings, chiefs, warriors, priests, commoners, slaves and “agriculture.”

Curiously (and rather tellingly), those efforts were pursued just as eagerly in communist Vietnam as they were in capitalist Thailand, and the euphemistic campaign slogans used on both sides of the political divide sound eerily similar. It is obvious that both systems don’t tolerate any alternative to the singular system of the state.

Do you notice that many of the fruits in Borneo do not grow (or grow well) in Thailand and Peninsula Malaysia? It is climatically similar and close by but the ecology different I guess.

Fascinating as always. Thank you for writing this. I look forward to the next installments.