An Animist Critique of Vertical Farming (and the Automation of Farm Work)

Exploring the moral implications and considering the plants’ perspective --- [Estimated Reading Time: 40 min.]

Vertical farms have caused considerable hype in recent years, and are hailed as the holy grail of future food production in pro-tech communities. Newspapers, techie blogs and magazines brim with upbeat news about this high-tech method of food production and praise the supposed possibilities to “feed the future”, “solve food supply issues”, and eradicate a number of environmental problems.

Are vertical farms actually a solution? Can they really feed us? And, considering the traction the animal rights movement has gained and the totally reasonable questions it raised about factory farming, is it ethical to grow plants like this? Can the food harvested in those institutions be healthy and wholesome? And, a question that regularly gets ridiculed, but one that we can’t avoid to ask in the light of recent developments in the fields of plant neurology: how does this way of “farming” affect the plants? How do they feel about it?

If your response is: “What the hell – ‘Plants feel?!’ What in God’s name are you smoking?”, this article is not for you. Go and read a book on plant intelligence, like Plant Behavior and Intelligence, Brilliant Green: The Surprising History and Science of Plant Intelligence, The Revolutionary Genius of Plants: A New Understanding of Plant Intelligence and Behavior, The Hidden Life of Trees, Thus Spoke the Plant: A Remarkable Journey of Groundbreaking Scientific Discoveries and Personal Encounters with Plants, Plant Intelligence and the Imaginal Realm, The Secret Teachings of Plants, The Lost Language of Plants, A Critique of the Moral Defense of Vegetarianism (Chapter 2), or Communications in Plants: Neuronal Aspects of Plant Life. People who dismiss plant intelligence, sentience, self-awareness and agency are usually those who are not informed about the latest scientific findings (or the oldest traditional wisdom, which turns out to lead to the same conclusions).

First of all, let me make clear that this is not a defense of conventional farming. I condemn conventional agriculture at every opportunity I get, and I am well aware that this practice is inherently destructive, unsustainable, and irreformable. The subsistence mode I have in mind for us humans is something else entirely, something tested by millions of years of evolution, not a few centuries of trial and error or a few decades of data science. But I will get to that.

The techies that populate the vertical farm landscape always focus on what vertical farms use less of, while meticulously avoiding to talk about every material they need more of, like steel, plastic, aluminum, concrete, copper wiring, computers, microchips, camera lenses, sensors, photovoltaic solar panels and wind turbines.

Furthermore, this will not be a purely rational analysis of the many economic downsides and hidden costs of vertical farming, since that has been done in great detail already and I have little to add to this. I will focus mostly on the moral, cultural and emotional aspects, since those are the factors that usually get ignored and dismissed too easily, for fear of not being taken seriously. But, again, if you don’t take me seriously for not adhering to the dominant materialist worldview, this article is not for you, and you should take a basic course in ecological empathy or environmental awareness, and check your (human supremacist) bias.

There is, of course, no shortage of material aspects to critique when it comes to vertical farming, starting with the claim that this practice is “more sustainable” because it uses less water and land. The techies, data scientists, venture capitalists and startup hipsters that populate the vertical farm landscape try to dominate the narrative by focusing on what vertical farms use less of, while meticulously avoiding to talk about every material they need more of, like steel, plastic, aluminum, concrete, copper wiring, computers, microchips, camera lenses, sensors, photovoltaic solar panels and wind turbines (for the “green” electricity that’s supposed to power those farms) and the host of rare earth minerals and metals that all modern technology requires. They don’t talk about the absolutely and utterly disastrous environmental impact that the mining and refining of those materials and the production of those machines and components have on ecosystems, but act – like all techies – as if technology just appears at the end of a factory assembly line with no strings attached (or, if they admit that the production of technology causes pollution, they downplay its severity and assure you that very soon some new technology will be invented to recycle the waste products or turn them into inert compounds – “I’ve seen an article about it on Mashable!”).

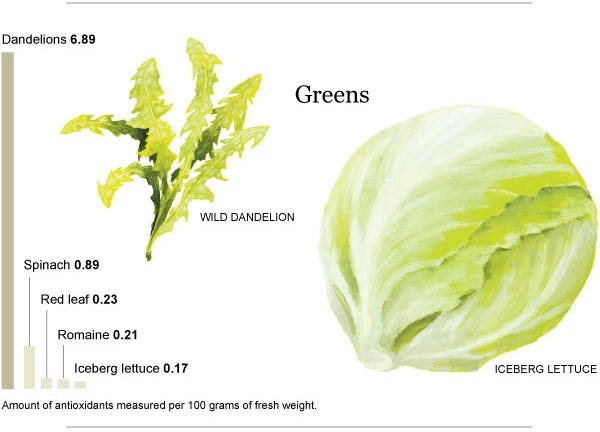

Another misconception is their (cl)aim to “feed the world”: “the world” (anthropocentric terminology for “only one species”) eats mostly grains – wheat, rice and corn – and those can never – never – all be planted in vertical farms. The material requirements would be too high, the utility bill too long, and the space required too large to ever supply a considerable portion of people’s diets. This particular technique will be forever limited to a few greens and small vegetables.

But first, let’s focus on the main components of those “farms”: the plants themselves.

For starters, plants are self-aware. Every living being is. Even bacteria and viruses are. Self-awareness is a prerequisite for being alive, since you have to be able to differentiate between other beings and yourself, or else you end up consuming your own body, or spilling vital organs and valuable metabolites into the environment, or feeding someone else. Moreover, they are intelligent. Every living being has to be. Otherwise you won’t survive. If you don’t respond to external stimuli, if you don’t react to threats and opportunities, if you don’t master the challenges your environment throws at you, you are, literally, dead. Plants can see; they receive light through photoreceptors all over their bodies, and analyze wavelength, intensity, angle of impact, obstacles between them and the light source, and can therefore tell the time of the day and what surrounds them. Plants can hear as well, they respond to vibrations of all wavelengths, and some plants can identify predators by the sounds of them chewing on leaves, even if they don’t eat their own leaves (others identify predators by the composition of their saliva). They produce defensive chemicals as a response, or call for help from other species by releasing volatile pheromones into the air that attract insects that feed on those eating their leaves. Plants are known to respond to touch, the most famous examples being the Venus flytrap, Dionaea muscipula, and the rapid closure of the leaves that Mimosa pudica incites upon being touched, and Mimosa learns fast if a sensation is not harmful and stops reacting. Since plants can’t flee like us animals, they developed sophisticated mechanisms to evade threats, defend themselves, or simply to regenerate after suffering extensive damage, with some plants able to recover even if they lose 90 percent of their bodies, and even the smallest grasses survive being rolled over by a car a million times their weight. Some plants don’t just accept any random pollen a bee happens to bring to them, but instead “mate selection is elaborate and underpinned by discriminating, complex conversations that precede and follow fertilization”, according to plant scientist Anthony Trewavas, a leading expert in the field of plant intelligence. Yes, plants communicate as well, via volatile pheromones (with other plants) and electrochemical signals (with other parts of their own bodies). Plants trade with subterranean microorganisms, releasing a nutrient solution composed mainly of starches or sugars in exchange for other nutrients or protection, and they go into symbiotic long-term relationships with mycorrhizal fungi, connecting their roots with the fungi’s hyphae, in order to obtain nutrients that are difficult to find and to communicate and trade with other plants that are also a part of this network, sometimes over considerable distances. Researchers have termed it the “Wood Wide Web” (even though it exists in all ecosystems with sufficient rainfall), so in a way plants invented the Internet long before our kind even thought of long-distance communication. Plants have developed sophisticated techniques to reproduce and to disperse seeds, making use of a broad spectrum of other species for both pollination and seed dispersal, and expertly utilizing the elements of fire, wind and water for the latter – all this long before any hominin made use of fire, or used water, let alone wind, to travel. Plants calculate possible outcomes, consider a large variety of variables, and make decisions based on those calculations. It is no exaggeration to say that plants think.

A single rye plant has over 18 billion root apical meristem cells (RAM’s), the plant equivalent to neurons. For comparison, the human brain has about 86 billion. Trees have considerably more, especially Old Growth. On a similar note, while the human DNA contains about three billion nucleotide pairs, one unassuming perennial herb in the bunchflower family, Paris japonica, contains a staggering 152 billion pairs.

(Interesting side note: while modern humans often pride themselves on being the “most complex” life form, in genetic terms this does not even hold true for the animal “kingdom” – the largest genome among animals is found in the marbled lungfish, Protopterus aethiopicus, with 130 billion base pairs.)

But enough of the technical jargon, and let’s focus on what really matters: how to appeal to the deep-seated biophilia, the wonder and awe we all feel as children towards the Living Planet and all its inhabitants, that slowly gets buried under anthropocentric myths and propaganda as we grow up. This biophilia is still there – it is an inescapable part of our Nature – but it has been hidden in a dark corner of our self, and only seldomly do we allow it to come out and astonish us with the tiny things Nature offers us, like ants carrying staggeringly large items of food, a lizard sunbathing on a stone, her skin reflecting the light in all colors of the rainbow, the complexity of a flower seen from up close, the shape of a particular plant’s leaf, or two butterflies chasing each other during their mating ritual.

If you think that to convince someone of your opinion you need unassailable arguments, crystal-clear logic, peer-reviewed studies and pure reason, think again. We humans are inherently non-rational beings, as should be obvious to anyone who has followed any public discourse about basically any hot-button issue, from abortion, over climate change, gun rights, immigration policy, vaccines, to gender issues. If we hold a certain opinion, it may be impossible to convince us of the opposite (or even consider some of the other sides’ points), even if we are confronted by the best logical arguments or hard, scientific evidence. And many (if not most!) decisions we tell ourselves were made based on “logic” are actually decided subconsciously by our emotional self – only afterwards does our rational self start searching for arguments in its favor. The emotional aspect of any controversial topic is one that can’t simply be ignored, and that should be addressed as seriously as any factual one. If a certain topic makes us feel a certain way, we should explore why. Then we understand why so many people continue to vehemently oppose genetic modification of living organisms, even though the majority of scientists say it is “safe” to grow and eat them and Big Agriculture spends fortunes on propaganda to change peoples’ minds. It just feels wrong, and no amount of “data” can change this feeling. If some people object to having unknown chemicals injected into their bodies, they do have a valid emotional reason for feeling skeptical, no matter what “rational science” says. And if we feel that factory farming is wrong because of what it does to animals and how it makes us relate to other animals, we have to carefully consider how we feel about vertical farming, what it does to the plants, and how it makes us relate to the plants. We have to open our hearts to even the smallest, inconspicuous herbs, see that they are living, breathing beings like us, and try to understand them based on our similarities, not our differences. We should put ourselves in their position and ask: what would we want?

So, let’s talk about vertical farms. Let’s talk about how they make us feel, and what those feelings might imply. Just as animals’ rights activists encourage us to put ourselves into the position of a cow in a CAFO (concentrated animal feeding operation) or a hen in a battery cage farm, I think it’s equally important to consider what plants grown in vertical farms go through.

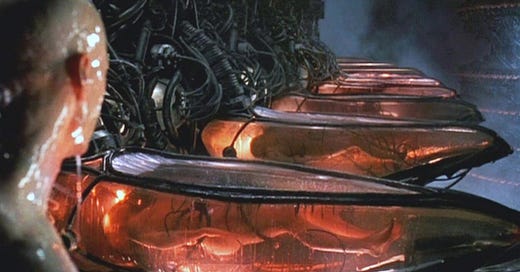

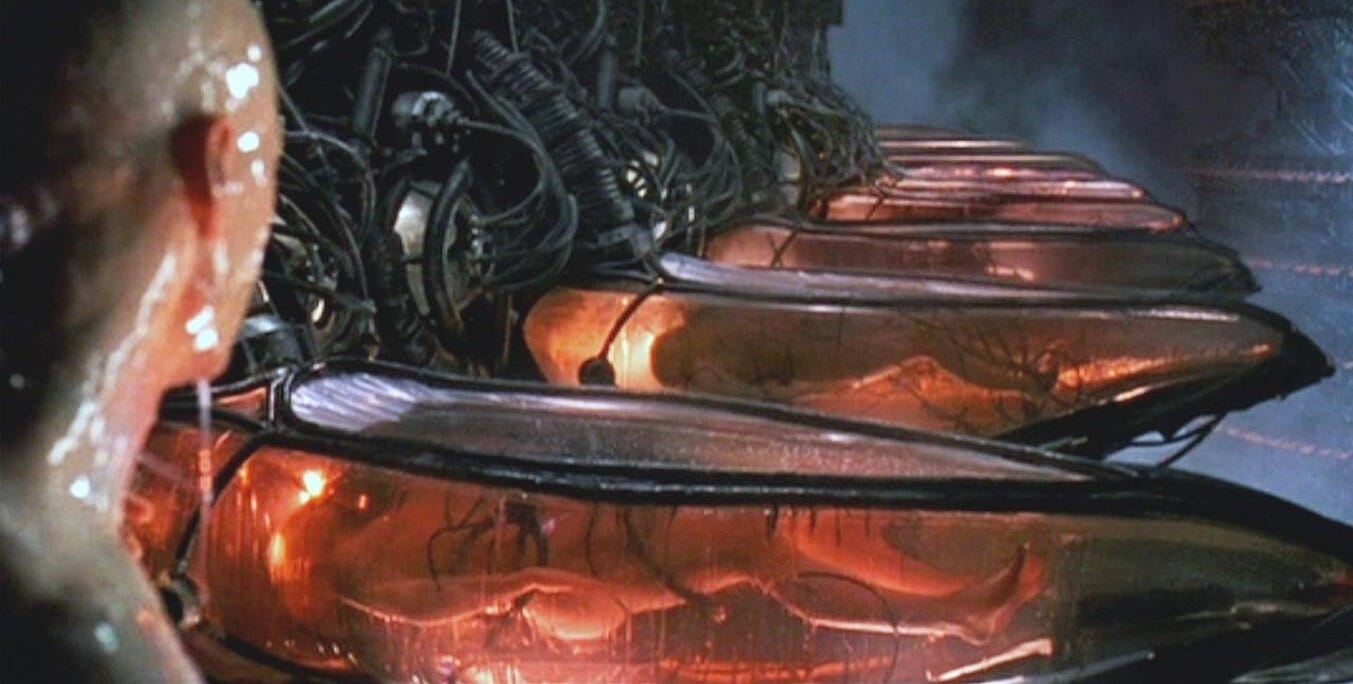

If you want a slight idea of how life in a vertical farm feels for a plant, contemplate this: growing plants in a sterilized medium they never encountered before, and feeding them artificial nutrient solutions is akin to suspending you in the air in a gigantic prison illuminated by rows of orange-colored LEDs (a wavelength that’s supposed to simulate sunsets, which research has shown to calm humans) and having a robotic arm force-feed you in regular intervals. Not whenever you’re hungry, but according to what intervals their calculations have shown to result in maximum weight gain. Not whatever you like, but a mixture they decided stimulates your growth best - a slimy brew made of starch, protein powder, vegetable oil, refined sugar, and a little salt, accompanied by a few pills containing synthetic vitamins, amino acids, and mineral extracts. Everywhere you look, in all directions, there are others chained up in the same position, all exactly the same age as you, a desperate and fearful expression on their faces, or, even more scary, completely emotionless. You search frantically for familiar faces, for anyone besides the single species you captives are comprised of; your hands and feet grope for a surface you’re familiar with, one that gives you hold and stability – without success. You strain to hear the buzzing of bees, the chirping of grasshoppers, or the song of birds, sounds your ancestors have enjoyed ever since they came into existence. But you won’t find either. You’re trapped, helpless, completely dominated by forces that are beyond your grasp, and the only sounds you hear are the cries of those you’re imprisoned with, to the steady background hum of the mechanical whizzing, whirring and beeping of machines.

This is the experience of every individual plant being cultivated as food crop in vertical farms: their roots never touch the soft, moist soil teeming with life that their kin and their ancestors have grown in since time immemorial, they are never allowed to explore the soil ecosystem and forage for food, make friends, and fight off predators both above- and belowground, their leaves are never warmed by sunlight that has served as their sole source of energy ever since the first plant started sending her roots downwards into the mineral sediment and her stalk towards the sky. They never experience the changing of the seasons, or the cycles of day and night, or of the moon, and they never hear the slow but steady heartbeat of the Earth. They are never tickled by the trunks of butterflies or the fluffy legs of bees, and they never have a chance to partake in the myriad simultaneous and multidimensional conversations between other plants of different species and families that their relatives outside the walls of the prison spend their days conducting.

“But they have everything they need!”, protest the perpetrators who – without irony – call themselves “farmers of the future”. Well, arguably so does the human in the allegory above. While everyone would agree that the poor bugger certainly lacks a great plentitude of things, above all social contacts and a sense of community, as well as the experience of freedom of even the most basic kind, nobody seems to be suggesting the same for plants. Yet plants, if left on their own device, grow in tight-knit communities and can decide crucial aspects of their lives for themselves (such as which shape they take, in what direction they direct their growth, whom they want to mate with, how many fruits they produce, what mycorrhizal connections they forge, and where they forage for water and nutrients). They act as individuals, never growing into the exact same shape, even if cultivated under the exact same conditions. Even clones never look the same, as everyone knows who has ever propagated bananas from shoots. If two plants look the same to you, it is because you don’t look closely enough.

“It’s the safest environment for plants!”, they might object. Well, as the saying goes, what doesn’t kill us makes us stronger, and the same is true for our distant relatives, the plants. Many of the most beneficial phytonutrients (for human health) are actually natural insecticides and repellants (they are responsible for the refreshing sting you feel when eating mustard greens) that are produced in response to environmental threats and stress factors such as herbivores or insects feeding on them. Vertical farms eliminate those threats, and you can imagine what that does to a plant. Just like a human whose needs are all catered to and who never has to solve any problems or respond to existential threats will be considerably weaker, more insecure and more prone to disease, mental illnesses and other ailments than one who does, and someone who never plays in the dirt, grows up in a sterile environment and follows overly strict hygiene regimens will likely develop all sorts of allergies and autoimmune diseases, so plants in a completely controlled and “safe” environment will lack certain crucial aspects that wild plants possess, and have no means to defend themselves against germs and other threats.

It's like the popular meme with two pictures of lions, one in a cage, and one lying in the savannah grass with a lioness by his side – the caption reads “One of these lions has security, free food, free shelter and free medical care. The other has no such guarantees to quality of life or security. Which one would you rather be?”

Plants grown in sterile environments never have the chance to develop their equivalent of an immune system, which is why vertical “farmers” have to dress up like surgeons when they enter their growing space. Any contamination with bacteria or viruses can prove fatal for the entire crop, as diseases rapidly spread in any population unable to ward them off by themselves.

Another important factor to consider is the arrogance that underlies any claim that we know what a plant needs. I myself don’t claim to know exactly what plants need, I just know that there’s a lot more that we don’t know.

We need wild foods: bitter, astringent and sour plants, and meat from wild animals that feed on wild plants. Only those wild foods contain the full spectrum of nutrients needed for optimal health.

The reductionist (or scientific) worldview (wrongly) assumes that we can break down what plants need into a number of chemical elements: first and foremost, Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Potassium, called macronutrients, plus a small number of micronutrients. We think we now know exactly what plants need, just like 19th-century scientists were sure that plant nutrients are limited to the macronutrients. If we look at the analogy to human nutrition, the flaws become obvious: we humans need much more than just carbs, proteins, fats and a number of minerals and vitamins to be healthy – we need, for instance, a host of beneficial bacteria in our food (or better, the largest microbial diversity possible), and dietary fiber to keep the bacterial populations in out guts healthy and maintain the delicate microbial balance without which we quickly succumb to autoimmune diseases or other illnesses. We need wild foods: bitter, astringent and sour plants, and meat from wild animals that feed on wild plants. Only those wild foods contain the full spectrum of nutrients needed for optimal health. In addition to the few dozen vitamins officially recognized today, there might be hundreds or even thousands more, yet to be discovered. Deficiencies of those still unknown vitamins might not express themselves as clearly as scurvy indicates a vitamin C deficiency, but they contribute to cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, Alzheimer’s and other modern scourges in the long term.

It was only in the last few decades that we began to grasp the utmost importance of the bacterial symbioses happening in our guts, of the staggering variety of phytonutrients found in wild plants that help prevent some of the top causes of mortality in today’s world, and of other plant metabolites that the modern industrial diet (also called SAD, Standard American Diet) lacks.

Likewise, plants crave a staggering variety of molecules and substances that they usually obtain from soil microbes in exchange for root exudates, from mycorrhizal fungi in exchange for sugars, or through the air from other plants, and without which no plant can be considered whole, happy and healthy. They survive, yes, they show acceptable amounts of macronutrients and even some vitamins, yes, but that’s not the whole picture. We can only measure what we know to exist and know how to measure. Moreover, there is no reason to believe we know even close to everything there is to know about nutrition.

Maybe there are compounds that plants can only produce, or mental states (see next paragraph) that plants can only achieve, if they receive and utilize the full, broad spectrum of unfiltered sunlight. Growing plants under LED lighting with a fraction of the wavelengths included in natural light might lead to unexpected deficiencies that only express themselves in the long term, both in the plants and in the humans who consume them.

Furthermore, plants produce and use similar neurotransmitters and hormones as are found in animals’ brains, which implies that there are, like with us animals, different emotional states for them as well. And those definitely have some sort of effect on the composition of the entire plant. Just as constant high levels of cortisol, the long-term stress hormone, make you unhealthy and cause a broad spectrum of maladies, plants produce a different spectrum of hormones and neurotransmitters when cultivated in completely artificial environments. Just like the way non-human animals are slaughtered can have a direct influence on taste and texture of their meat (if their last moments are spent in agonizing terror their meat will become tougher and lose some flavor, which isn’t the case if they are killed fast and without inflicting too much pain in the process, or if they die alongside someone who comforts them in the last moments), plants might also produce a different set of phytonutrients and other compounds, which might, as with meat, have direct consequences for nutritional density or even toxicity.

As an organic gardener, I have abundant personal experiences to attest to nutritional differences between naturally- and commercially-grown vegetables. Whenever we eat out, we are very careful not to eat anything too spicy – not because we can’t “handle the heat”, but because conventionally grown chili (there aren’t many organic restaurants in Thailand’s countryside) almost inevitably leaves you with an unpleasant burning sensation in your stomach that might last for up to an hour. This never happens with chili we grow ourselves, even if we plant commercial seeds of the exact same variety, and even if we use a lot of it (our record is a bowl of papaya salad with 72 chilies). Fertilized with nitrogen salts and superphosphate and doused in poison, the plants seem to produce too much of a certain compound that causes this stomach burn. It most definitely isn’t healthy, especially not in the long term.

When we didn’t have enough ginger yet, we used to buy commercially grown ginger from the market to make ginger tea – massive rhizomes – whose consumption provoked a rather unpleasant burning sensation. Of course, you have a similar burning sensation with organically grown ginger – which is often smaller, but even more “spicy”, implying that commercial ginger contains plenty of water, while organic ginger is like a more concentrated form – but the experience is a very different one. It’s as if the compounds in organic ginger are simply more balanced. On several occasions we encountered Chinese kale in restaurants that tasted like glue (no exaggeration!), and yard-long beans from the market that are chewy, watery, and have a sponge-like texture, whereas ours are sweet, crunchy and firm. I’m confident everyone who eats organic, naturally-grown food, even if only occasionally, has had similar experiences.

To be fair, most “produce” grown in vertical farms doesn’t contain much else besides water anyways (it’s mostly nutritionally worthless salad greens), but a lot of smaller hydroponic farms, for instance, already grow chilies, tomatoes, strawberries and the like, and they are planning on expanding this list. Many of the experiences described above are caused by sterile soils, chemical fertilizers and pesticides. They all indicate an imbalance in the plant’s environment that leads to a different nutritional composition of the plants’ body – hence a different taste – and while vertical farms pride themselves on being pesticide-free, the environment is still completely sterile and the plants are still fed chemical fertilizers. Only plants that can choose for themselves what they eat and what not, how much water they drink, and what defensive chemicals to produce (remember, those “natural pesticides/deterrents” are often compounds that are healthy for humans!) can build nutritionally balanced bodies, fruit and seeds that don’t have negative health impacts for those eating them. Only wild plants – not lettuce! – contain the nutrients we need to be healthy.

Vertical “farmers” think of the plants that feed them as data points, variables in an algorithm, matter to be manipulated and transformed, a product to be improved and marketed, and an opportunity to get rich and pay investors dividends.

Data scientists and engineers under the illusion of being “farmers” are sure they know what plants need, yet in fact they don’t have the slightest clue. In some cases, they go as far as to proclaim that they “understand plants better than anyone else [emphasis mine]” (uttered by Stacey Kimmel, PhD, VP Research & Development, Aerofarms, in a promotional video) – one of the most outrageous and ludicrous claims I’ve ever heard them make. They don’t even touch the plants! They look at graphs and charts on a computer screen, and if that’s what they think “understanding a plant” means, then it’s not only plants that they don’t understand. They think we need computers and sensors to understand plants, when in fact all we have to do is open our hearts to them and intimately pay attention to their needs and desires. If we really try to understand plants, we immediately realize that one thing they definitely don’t want is to live in vertical farms.

Vertical “farmers” think of the plants that feed them as data points, variables in an algorithm, matter to be manipulated and transformed, a product to be improved and marketed, and an opportunity to get rich and pay investors dividends. They might laugh at comparing a salad plant to a human being, or even get angry at what in their eyes is tantamount to blasphemy. Their religion is humanism: the worship of the human, of human capacities and intellect, inventions and innovations, and the human mind. (Tellingly, in the promotional video linked above, the founder of Aerofarms said that his company is “feeding the planet” – “the planet”, in his anthropocentric and reductionist worldview, meaning one single species, humans, the only species that really matters.) This peculiar belief evolved from a religion whose god created humans in his image (right after hastily creating all other animals, and who seemed so unconcerned with plants as living entities that the origin myth doesn’t even mention them being created); it went through an upheaval when those humans declared their god dead (or straight up denied his existence in the first place) and became the new gods themselves, equipped with scientific methods of truth-finding, sacred scripts called “studies” whose results commoners should never dare to question, and technology as their ultimate tool and proof of their mastery, to become the lords of the world and eventually the rulers of the entire universe.

They see plants as resources to be exploited, and food as being just another thing we produce, like glass, or plastic. If you view food as just another industrial product, then the logic of capitalism (which dictates efficiency, economies of scale, and utter disregard for the long-term consequences of your actions) justifies completely automated vertical farms as being the next step of food production (but don’t dare to imagine what the last step might look like – maybe an industrially produced, wholly artificial nutrient sludge, completely eliminating any contact with the non-human world, any interaction with the Living Planet?). The difference is that we don’t need glass or plastic to survive, but we absolutely and unequivocally need food.

To even talk of “food production” has implications for the way you perceive the world. Production is, according to French professor of anthropology Philippe Descola, a “heroic model of creation”, steeped in the biases of the dominant culture. If you produce something, you act as the sole autonomous subject, imposing form upon inert matter, order on chaos in an almost godlike manner, according to a pre-established plan and (usually selfish) purpose. The concept of production presupposes a naturalistic materialism, of seeing other Living Beings as semi-random conglomerations of molecules and atoms, lifeless matter, purposeless means to an end – an end that, with the production of food, leads straight into your mouth. We need to eat, as annoying as it may seem to some, so let’s get it done in the “most efficient and cost-effective way”.

If you produce something, this means that there is a radical difference between the ontological status of the producer and that of whatever he produces. This is why we speak of food production, not of food acquisition, food procurement, food harvesting or simply food gathering.

Most importantly, it is in either case definitely not “us” who produces any food. If anyone, it’s the plant herself. We just plant, care for, and harvest. Actually, that’s a blatant romanticizing of farming that doesn’t reflect the reality of modern agriculture, so let’s try again: we just alter the DNA of the seed to best suit the purposes we have in mind with utter disregard for the needs of the plant, inject those seeds into sterile soil through a contraption of metal tubes pulled by large machines, irrigate the young seedlings with non-renewable fossil water from aquifers, fertilize them with nitrogen salts and mined phosphate and repeatedly douse them in toxic chemicals, and harvest them using massive soil-compacting machines – and all that without ever having to even touch the plant. This can only be considered producing food in the sense that you call extracting gold from crushed ore using highly toxic mercury producing gold. It is never us who do the producing, we just extract, exploit and pollute.

To cut vertical “farmers” some slack, they do have some good points that need to be addressed when it comes to the deficits of conventional agriculture. Proponents of vertical farming rightly criticize the inherent destructiveness of agriculture, things like groundwater depletion, soil erosion, the toxification of entire landscapes with pesticides, the algae blooms, oceanic “Dead Zones” and other sings of an environment thrown into imbalance by the sudden influx of large quantities of macronutrients, resource depletion of phosphorus, the energy required (and supplied by fossil fuels) to produce chemical fertilizers (from a feedstock of more fossil fuels), and the dependence of farm machinery on even more fossil fuels.

Yet their “solutions” are diametrically opposed to what real solutions look like – they blindly follow the upwards curve that the Myth of Progress promises them, forgetting or ignoring that this curve always ends in collapse, usually after a brief period of exponential growth. No matter if we’re talking about resource consumption (leading to depletion), land usage (leading to habitat loss and biodiversity collapse), exploitation of living beings they call “natural resources” (leading to rampant deforestation and the depletion of both terrestrial and marine animals, concomitant with collateral damage to bycatch and the unfolding “Insectageddon”), energy consumption (leading to global warming and climate breakdown), or abstract expressions such as “standard of living” (leading to widespread environmental devastation, as well as feelings of inadequacy, hopelessness, helplessness, purposelessness, listlessness, anxiety, and alienation among the population experiencing this surge in “standard of living”), this paradigm can only ever end in disaster.

Do they realize that traditional farming, up until a few decades ago (and still practiced in many areas of the world), doesn’t “use” any water at all, but simply utilizes already existing rivers or natural rainfall? Compared to those methods of farming, vertical farms use 100 percent more water.

Moreover, they only ever compare themselves to conventional, industrialized agriculture. Aerofarms praises their “better productivity, quality, and efficiency” – better compared to what? Do they realize that conventional field monocropping is not the only way to grow food? Do they understand that the oldest and most efficient systems, ecosystems, never contain only one species and never benefit only one other species? Do they know that there are methods of farming that mimic natural ecosystems and work with, not against, other species?

Have they ever heard of permaculture?

And, even if they did, would they ever consider it an alternative, since it is based on less technology, and less control? Their answer is always more, not less, despite the obvious futility of this approach. “More is better than less”, teaches the dominant culture.

To be fair, permaculture does create “more” as well – more diversity, for instance, a criterion by which vertical farming loses even against industrial agriculture, which allows at least some insects, rodents, birds and microorganisms to coexist with crops – but simply “more” is not the underlying motivation of permaculture. Permaculture’s underlying motivations are instead concepts like balance, stability, resilience, and sustainability – not growth at all costs. Optimally, diversity should be a crucially important factor in farming, which is why vertical “farmers” usually avoid talking about it. It is the key to efficiency (and to resilience), and no food system is as diverse, efficient and resilient as permacultural multistrata food forests. Planting species together that like and benefit from each other automatically leads to healthy plants and high harvests, and achieves all that without sensors and computers.

But natural and ecological approaches to farming are no viable alternative for the techies, because they run counter to the Myth of Progress, the paradigm of civilization that “more is always better”. They represent a step backwards, and in the dualistic worldview of the dominant culture “back” is “bad” and “forwards” is “good”. Vertical farms might use over 90 percent less water and land when compared to corn farmers in Iowa or “el mar de plástico” in Almería, Spain, but do they realize that traditional farming, up until a few decades ago (and still practiced in many areas of the world), doesn’t “use” any water at all, but simply utilizes already existing rivers or natural rainfall? Compared to those methods of farming, vertical farms use 100 percent more water – it doesn’t rain inside, so all the water they need has to be piped in.

And what is inherently bad about using land to grow crops? It all depends on how you grow them. If you wage an all-out war on “weeds” and “pests”, like conventional agriculture does, you violate the Law of Life (explained below), specifically the Law of Limited Competition that states that “you may compete to the full extent of your capabilities, but you may not hunt down your competitors or destroy their food or deny them access to food” – and the penalty for violating this law is, eventually, extinction. No other species breaks this law, and even for us humans there are many ways of planting food crops that don’t involve waging war on other species. If you help creating an abundant, multifaceted and diverse foodscape on degraded land previously used for monocrop agriculture, what is so bad about using land? If land is used like this, isn’t it a good thing? If you create habitat for other species, plant wild plants and native forest trees together with the species that feed you, who says people shouldn’t use as much land as possible like this?

The motivating factor behind the techies’ approach to solve problems created by agriculture is what I’ve termed the Old Paradigm: a worldview that, despite being explicitly formulated and encouraged by it, predates Christianity and is in fact as old as grain agriculture itself. It is rooted in the transition from foraging to farming, and the concomitant change in our perception of ourselves and our role in this world – namely, to use biblical terminology, that it is the sacred duty of humanity to subdue the rest of “creation”, or, as writer Daniel Quinn formulated it, that “the world was made for ‘Man’, and ‘Man’ was made to conquer and rule it.”

It is a pathological urge to control, force and exploit living beings and natural processes for the benefit of one species: ours (or, to be more specific, for the benefit of some members of one species).

“Control” is a reoccurring theme in the vertical farming sector, with companies shamelessly boasting how they completely control the “environment” of their crops and dominate the plants in every possible way. Expressions like “completely controlled environment” are standard industry talk and a source of pride for the techies. It’s the next step in the quest to completely dominate the world. We can’t (reliably) control the weather – when and where it rains, when and how much the sun shines and when the seasons change – so outdoor farming is inherently flawed because it subjects us to the whims of Nature and doesn’t allow us to exert the complete control we think we deserve. Indoor farming changes that. Here, we control everything, down to the last drop of water.

Modern humans, convinced of their superiority, can’t and won’t accept that we have to follow the same (seemingly arbitrary) rules that all other creatures follow – Daniel Quinn called this set of rules the Law of Life, a collection of evolutionary stable strategies that every living being follows. An example is the Law of Limited Competition quoted above. Every creature that doesn’t follow the Law of Life will eventually go extinct, since it thereby attacks the very foundations of coexistence, interdependence and interconnectedness that imbue the Community of Life. In defining our identity against all other Living Beings (we are humans – they are animals/plants/fungi), we can’t accept that what limits them should also limit us. We think the world should be ours, is ours, and if the world stubbornly rejects this notion, then the answer is to increase control and force.

To name but one example, all other animals have to eat whatever is in season – only modern humans childishly refuse to accept this for themselves. We acknowledge that this is how it has been for all humans until a few decades ago, but we’ve collectively decided that we “evolved beyond that”. We are in control of what we eat, and when. If I want tomatoes in winter, they better fuckin’ have some at the store, because it is my natural birthright to eat whatever I damn well please! Seasonality, following one of the most basic natural cycles, is perceived as a limitation on freedom, and for the techies “freedom” means having access to everything, all the time.

This is part of a wider trend of homogenization – not only eating the same vegetables all year round, but eating the same vegetables all over the globe. No matter if you’re in Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe or America, you’ll find lettuce, tomatoes, and cucumbers. The ultimate goal of Globalization is that everything is the same, everywhere – and that includes diet. Despite the staggering variety of nutrient-dense wild and semi-wild vegetables found along every roadside, riverside, and in every patch of forest, pasture, garden or fallow land here in Thailand, government sponsored “health ads” promote eating iceberg salad instead of fried chicken.

Most important for us as Living Beings, as members of the Community of Life and inseparable parts of the larger ecosystem we inhabit and depend on (no matter how much we try to deny it) is that vertical farming tries to sever one of the last links we have to the myriad other Living Beings that give their lives so that we can live another day: they are removing the human completely from any interaction with non-humans. While conventional farmers at least still see their plants, vertical farms could easily be operated in a completely automatic fashion. While you still see some humans scurrying around in most vertical farms today (usually tending machines, not plants), their inclination towards automation will sooner or later mean that you will easily be able to build a factory run by computers that automatically rolls out packaged food for distribution.

Urbanism has already almost perfected this new way of being, where humans interact exclusively with other humans and the machines they produce, in an “environment” (see how different they define the term?) that consists entirely of human-made materials. This trend spills out into all walks of life, and in agriculture is already plainly obvious in the development of such abominations as farm robots, which meticulously exterminate all other life forms, spray toxic chemicals and harvest crops, pollination drones (since the bees will go extinct anyway, right? – so there’s no need to even prevent this from happening), the automation of large-scale farm machinery such as irrigation systems and combine harvesters, and machines for milking cows and butchering chicken.

I always ask myself: what makes the techies so convinced that farm work is so terrible and undesirable? Have they even tried it?

I want people to learn to live not only off, but with the land, to feed ourselves without compromising other Living Beings’ ability to feed themselves. This subsistence mode, a combination of foraging and carefully modifying ecosystems to increase the density of food species, has worked successfully for millions of years for humans.

Richard Heinberg, senior fellow at the Post Carbon Institute, has famously called for “fifty million farmers” in the United States to create a new, sustainable, agrarian society – but I’d go further. I want five billion permaculturalists, taking back land owned by giant Agribusinesses and corporations and transforming it from ecological deserts into lush food-ecosystems that harbor all native species and foster the connection with the land that most humans have lost. I want people to help Nature regrow the forests and grasslands that agriculture destroyed, to help recreate habitat for all species that have suffered under the relentless expansion of agricultural land grab, and learn to live not only off but with the land, to feed ourselves without compromising other Living Beings’ ability to feed themselves. This subsistence mode, a combination of foraging and carefully modifying ecosystems to increase the density of food species, based on cooperation, care and foresight rather than control, greed and domination, has worked successfully for millions of years for humans. It is, in fact, the only subsistence mode we can be sure of is really sustainable: it was sustained, succesfully, for countless generations of humans, over millions of years, without ever depleting any resources or degrading the environment.

(Yes, prehistoric people contributed to the extinction of megafauna – together with climatic shifts – but those cases are well within the limit for natural background extinction levels. Extinction of megafauna happened on a scale of four species every one thousand years globally, and are simply a natural result of one species of predator slowly expanding its habitat.)

There is certainly no shortage of land for this endeavor, and with an intelligently designed multi-level permacultural system it is possible to feed more humans per hectare (with a healthier and more diverse diet) than with conventional agriculture, in all climate zones.

Gardening is one of the most fulfilling, meaningful and meditative tasks I can think of, and my personal experience has shown that the Void, the emptiness and discontent that so many of us feel deep inside ourselves, can’t be filled with the latest iPhones, fast fashion and other consumer goods. What we lack is connection, to other people, animals, plants, fungi and to the entire ecosystem we inhabit, and there is no better way to reforge this connection than to get out there, find a patch of land to rewild (the land and yourself), get your hands dirty, and fulfill your basic needs without the help of technology or strangers. I have written elsewhere that this is

“[…] a challenging but rewarding adventure, and you surely will never be bored again.

But be advised: while the simple life in Nature is much better than [e.g.] city life in terms of exposure to pollutants, stress, and other health hazards, it is far from being only idyllic and worry-free — sometimes it demands a certain amount of sacrifice from us. We will have to bleed, sweat and cry at times to overcome obstacles. Our hands will blister, we will cut and bruise ourselves, but we will simultaneously remember how good it feels to be alive. Every time a small but annoying wound (like from a thorn in the foot) heals, we will rejoice with our regained abilities, and every time we will feel like a part of us has been reborn. Every time an injury closes, we will regain a bit more trust in ourselves and our body’s healing abilities. We will feel more connected to ourselves, our surroundings, and become more confident with using our body. We will become physically stronger and harder, and we will gain wisdom and knowledge faster than we might imagine. Over time, we will learn a lot, we will master skills, and become more satisfied with ourselves. We will rediscover what it means to be a human and how good it feels to be part of this beautiful, awe-inspiring, gigantic ecosystem we call Planet Earth.

Living a self-sufficient, natural lifestyle is more rewarding than anybody working a regular job in the city can imagine, yet it is not free of occasional frustration. But life is not supposed to be too easy, and it becomes boring fast if it is.

There is no greater joy than being able to feed yourself, to simply take a walk through the garden and gather enough food for the day. Feeding only yourself and your immediate community doesn’t usually require much of an effort anyway, no matter where you live (compared to the 8-hour working day). Building your own house, living in it from day to day with your loved ones, and repairing it when necessary, will fill you with more pride and joy than any apartment, loft, row house, or mansion in the city ever could — even if it turns out to look “less professional” (which is just a pessimist way of saying “more unique”).

The self-sufficient lifestyle will gift you with more freedom, leisure time, and self-determination than you’d find anywhere in the world of employment.Lend an ear to those who already went through the first steps, and they will reassure you that it is not only possible, but that it’s wort it.”

I always say that everyone can enjoy this lifestyle, if they allow themselves to let go of their ingrained biases and open up their hearts. The key is to simply try, not just for a week or two, but long enough to see the trees grow. If you’ve lived in the same place long enough to witness the healing of the land, the power of Nature to create, regrow and thrive, it’s impossible to ever go back to enjoying industrial life.

Another factor we always have to consider is climate change. Harvests are already decreasing in many parts of the world due to droughts, floods, or other extreme weather events. Conventionally-farmed monocultures are especially vulnerable to those climatic changes. Even vertical farms are not safe, since increased electricity consumption exacerbates global warming (even if your electricity comes from solar panels), and a warmer climate puts more stress on the electrical grid. In case of a power outage vertical farms will be rendered useless in a matter of seconds. Those are all problems that permaculture farms don’t have to be afraid of. Outdoors, plants grow no matter if the power is down or not. Diverse food-ecosystems cope much better with environmental stress, and even if in the event of a flood, drought or storm some crops fail, there are always other crops to fall back on.

You can’t feed yourself without killing other living, sentient beings, but it is our moral duty to limit the amount of suffering to both animals and plants that we consume.

Does it really make sense to increase our reliance on technology to fulfill our most basic needs? Can this approach ever be sustainable? Is the only direction to further alienate ourselves from all non-humans?

Is the “future of food” really what basically amount to concentration camps for plants, after already building concentration camps for domesticated animals? Where does this kind of thinking lead us? What will the techies’ next “great innovation” look like? Can we be any more disrespectful towards the creatures that feed us, that give their lives so that we may live another day?

You can’t feed yourself without killing other living, sentient beings, but it is our moral duty to limit the amount of suffering to both animals and plants (and fungi, people always forget fungi) that we consume. It is of utmost importance to respect all life forms, whether they look like us or not. Everything else is just a perpetuation of the same old human-centered worldview, at best with the mantle of protection being expanded to include a few species that more closely resemble ourselves, as proposed by vegetarians and vegans. Yet this is neither enough nor does it address the underlying paradigm that allows us to treat the world as an Other. What we do to the world, and to every living being in it, we do to ourselves, one way or another.

Ask yourself this: How would you like to live? In an artificial environment completely controlled by humans, under artificial lights, alone and isolated in a vertical farm - or outside, roots digging into the soil, the sunlight warming your leaves, in a diverse, tight-knit community of thousands of other plants, animals, fungi and bacteria?

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/aug/17/indoor-vertical-farms-agriculture?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other

In the guardian today

Apparently reality slowly catches up with the hyperalienated techies that thought you can innovate and engineer your way out of food shortages through technology, increased control, and the ultimate domination of living organisms. Turns out all this is a lot more expensive than originally thought, and rife with other problems.

https://www.fastcompany.com/90824702/vertical-farming-failing-profitable-appharvest-aerofarms-bowery?fbclid=IwAR3wmsXxdwqz6OBTdjoKWIt3QYZDhWRo7F41mVF9Zk7LCBX9VH_L4iY0dPs

There are few things I hate as passionately as vertical "farms," so you can imagine how good I feel when I read about multi-million investments gone sour because people tried to improve upon Nature.

Hopefully this helps people realize that Silicon Valley investors are not the super-smart thought leaders spearheading the transition into high-tech utopia they imagine themselves to be, but pathetic, disconnected computer nerds who think life is a video game - the lesson we can learn is that whatever Silicon Valley plastic people do, we should do the exact opposite.

While still containing plenty of stupidity and hopium, it's definitely an article worth reading, despite its length. As they say in Germany, "Schadenfreude ist die schönste Freude!" - Schadenfreude (finding joy in someone else's misery) is the most beautiful of joys.

From the article:

"Adding renewable [sic] energy outside can help—and reduce the carbon footprint that goes along with that energy use—but putting a few solar panels on the roof can’t cover the total amount of electricity needed. 'In a typical cold climate, you would need about five acres of solar panels to grow one acre of lettuce,' says Kale Harbick, a USDA researcher who studies controlled-environment agriculture. A hypothetical skyscraper filled with lettuce would require solar panels covering an area the size of Manhattan."

"Startups have also wildly overestimated how quickly they can grow. AeroFarms, for example, said in 2015 that it hoped to build 25 farms in five years. Instead, it currently has two large commercial farms in the U.S. and an R&D facility in Abu Dhabi. And they’ve overestimated how quickly they can make money."

"Gordon-Smith says that most vertical farms in the U.S. are a long way from profitability. 'Based on an analysis we did for a large private-equity firm, we don’t actually see a scenario where in the next 10 years vertical farming will compete with field-grown at scale in North America,' he says."