The day on which the pond was half full

Reality is knocking, harder and harder. When will we answer? --- [Estimated reading time: 20 min.]

Disclaimer: Don’t read this if you had a good day, and don’t read it if you had a bad day. It will mess up your good day, and it will make a bad day even worse. Instead, I recommend reading it in a moment of intellectual clarity, in which you can examine thoughts abstractly without letting them get too close to your heart initially. It can be difficult to ponder the topics addressed herein, but unfortunately that’s just another inescapable aspect of the times we find ourselves in.

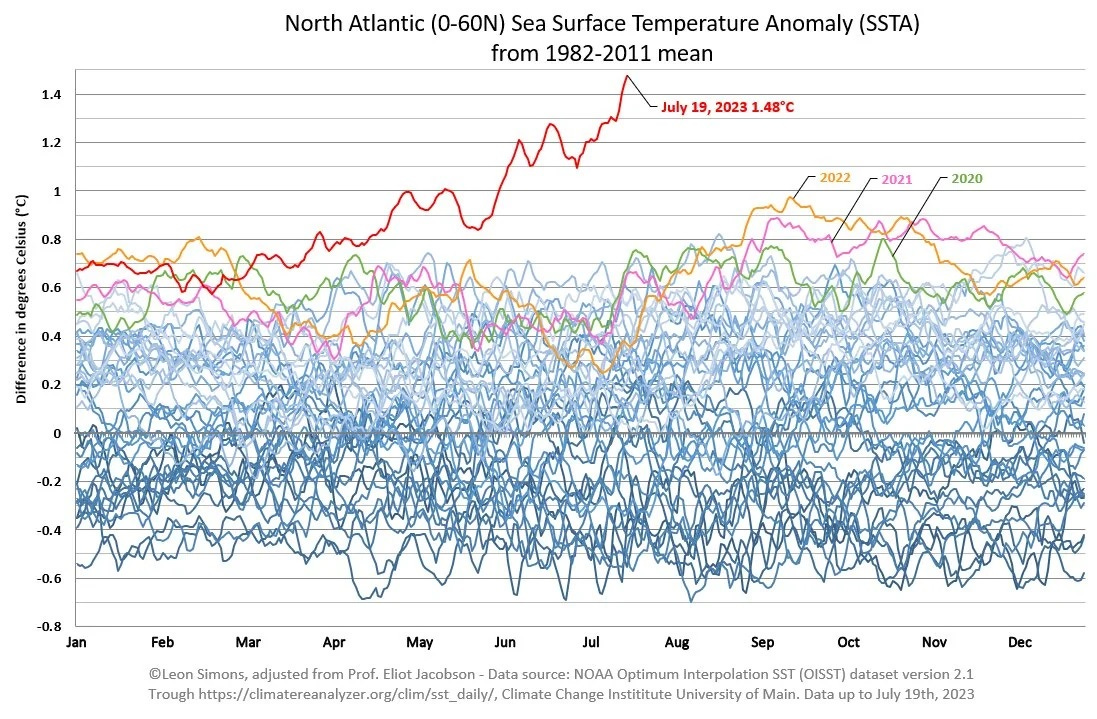

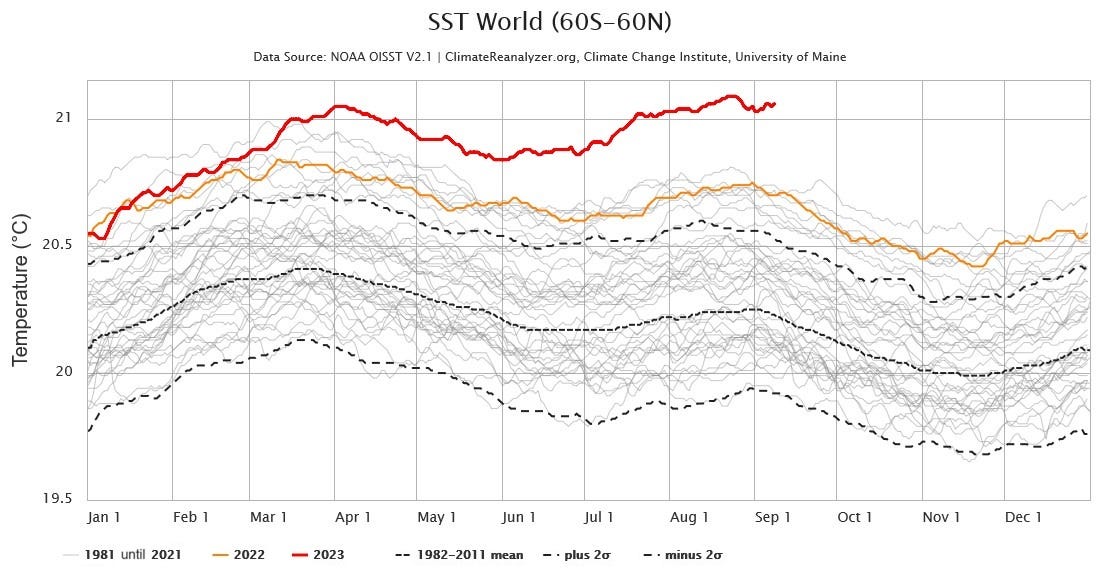

It’s one of those days again. They seem to increase not only in frequency, but also in intensity, as we spiral ever closer around the abyss. I’m writing this because some thoughts are easier written than said out aloud. This is the year in which the graphs describing everyday life around us started turning visibly exponential. It all started with the widely shared graphs showing the North Atlantic Ocean Temperatures, that were updated weekly to reflect the latest changes, and several times the y-axis had to be extended to accommodate the record heights the graph was climbing towards. Something was seriously off the charts here. Soon after, graphs describing Antarctic sea ice extend followed. The same trend, just inverted.

Instead of a gradual, linear change, as in previous decades, the graphs depicting the current year rose or sank well above or below the average. And it has been getting worse steadily.

The graph that prompted me to write this article was the one describing the extend of the Canadian wildfires. It was like a punch in the face. We are just beginning to feel the effects of all those greenhouse gases we’ve been emitting so busily over the past century - but this really doesn’t look good. Logic tells us that an exponential increase in greenhouse gasses (combined with a whole legion of other environmental factors influencing the climate, like the drastic reduction of forest cover caused by civilization, that all look exponential) will ultimately lead to an equally steep increase in a bunch of other things, including possibly the global average temperature. Remember, we’ve been on the Business-As-Usual path ever since the first climate conferences were held over 30 years ago.

But it still feels unreal that this is actually happening now.

It also feels surreal to sense genuine existential dread creeping up your spine when looking at curved or jagged red lines rising or falling that appear periodically on the screens in front of us. But that’s what’s become of this world. Abstractions over abstractions, to describe the simplest truth of all: everything is ephemeral, everything is constantly changing – and change is the only constant.

We have subconsciously assumed that growth will be linear, because our primate brains are not made for conceptualizing exponential growth. This has been shown countless times in high school math lessons all over the world, often with the example of a pond in which an aquatic plant (such as an algae) is introduced that doubles its surface area each day. The question is: if we know that the pond will be full on the 50th day, on what day is half the pond’s surface covered by plants?

Upon hearing this question for the first time, most people instinctively respond with 25 – I certainly did, math was never one of my strengths – only to be told that, no, it’s day 49. The area covered in algae doubles in size every day, so if the pond is full on the 50th day the algae population must have doubled its surface area overnight.

We, ladies and gentlemen, have arrived at “Day 49.” The pond is half full.

All those graphs we started to see diverging this year, those are indicators that the systems shift is accelerating. Change is underway, and it’s coming towards us fast. Much faster than feels comfortable. Of course, the metaphor I’m using here has its limitations: what is the pond, and what does it mean that the pond is full? Full of what?

First of all, “the pond” represents the climatic window in which agriculture (and hence civilization) is possible: the so-called Holocene. It can alternatively be the range of climatic variation in which our species evolved. Both of those thresholds are being crossed right now. Secondly, “the pond” being “full” means the atmosphere is saturated with greenhouse gasses and pollutants to such an extent that we enter unchartered territory, evolutionarily speaking. We are not sure how (or if) we will be able to adapt to those new climatic extremes in the long term, because it overshoots the boundaries of our species’ historical climatic niche. Thirdly, we are obviously not talking about literal days. “The pond” will not be “full” tomorrow, but if we think of time frames spanning approximately a decade each as “one day,” the metaphor works. The 2020s will be remembered as the day on which the pond was half full.

The day on which most of us still had access to the conveniences and pleasures of the previous decades, but it became undeniable that things were speeding up – that the Tower of Babel started shaking.

We're in this phase.

So far, we’ve seen a few crises converging, as I pointed out in my last essay of this kind. It looks a lot like a number of key aspects of civilization have started their slide down the latter half of the bell curve, as was expressed in the unofficial 50-year-update of the Limits to Growth report, which found that, so far, we’re on track for scenarios BAU2 (Business As Usual, but with double the initial resource stock) and CT (Comprehensive Technology, in which some still unknown technology will magically save us), which both align most closely to the empirical data observed. Which scenario will more closely align with our lived reality will become obvious only in the next few years, because the BAU2 and CT graphs only really start diverging in the 2020s. But so far we have absolutely no reason to believe that some magical future technology (like Carbon Capture & Storage or nuclear fusion) will save us from collapse, and even in the CT scenario, we see a drastic – if not rapid – reduction in food production and a levelling off of population, followed by a pronounced decrease in industrial output.

Both scenarios predict a decline in food production starting in the late 2020s or early 2030s, and lasting at least until 2050.

We’ve all been victims of a psychological bias that stems from the Pleistocene, the period in which our species evolved and that shaped who we are today. “Things change from time to time, yes,” we tell ourselves, “But the ice comes, the ice goes – it’s all cyclical. Right?”

And indeed, the climate changed fast at times during the Pleistocene - but not as fast as what we’ve been seeing lately. Not as fast as this.

Sure, the Eemian, the last 15,000-year-long interglacial, was even warmer than today’s world (with sea levels 6-9 meters higher than today, maybe higher), but the climatic changes happened gradually over thousands of years, so species could migrate and adapt – and we are already certain to surpass Eemian levels of warming.

It will be difficult for trees and most other plants to migrate fast enough to keep up with the shift in local climatic conditions, hence entire bioregions will be incinerated. This process has started already, and is now unstoppable. We’ve reached a tipping point, but few care to admit it. Few dare to admit it.

But think about it for a minute: do we have any reason to believe that in the next, say, five years there will be fewer wildfires burning, with or without human intervention?

Arnold Schroder (host of the most underrated podcast of the decade, ‘Fight Like An Animal’) expressed it as follows:

“To say we are past tipping points is to attempt to psychologically integrate an inarticulately painful truth. One anthropologist's list of a few dozen traits common to all human societies ever documented includes ‘demonstrably false beliefs.’ Even on an earth of infinite abundance and dazzling beauty, people inhabited narratives of how death isn't real, and how we're going somewhere even better and even more beautiful when we die. Convincing arguments can be made that the human mind, in most cases, is not strong enough to acknowledge the realities it is capable of perceiving. Why should the end of the world be any exception?”

And what were we thinking? That we could just crank up the engines and saturate the atmosphere with greenhouse gases, pollutants and aerosols in a geological blink of an eye, without anything happening? That the planetary ecosystem would just continue to meekly absorb our waste and forgive us our trespasses indefinitely?

Try to embrace the unthinkable for a moment, and contemplate the fact that the lines we’ve seen diverging from their usual historical range this year are part of a trend. As the scientists will surely not fail to remind us over the course of the currently unfolding El Niño, “this is all happening so much faster than we expected!”1 But, to quote Arnold Schroder once more, “how long can we say ‘it’s almost too late’ before we say ‘it’s too late’? How long will we say ‘this is happening faster than we predicted’ before simply acknowledging it’s happening exactly as fast as it is?”

A few years back, my mother told me a great metaphor she encountered that explains vividly how ecosystems change when under pressure: imagine a dump truck with a bed full of sand that is slowly being lifted. At first, not much will happen, apart from a few handfuls of sand sliding off the back of the bed occasionally. But once you reach a certain angle – a tipping point – the entire load suddenly comes rushing down, without any previous warning.

Increasingly large amounts of sand have been sliding off the bed of our metaphorical dump truck for decades now – the 70 percent decline in wild animal populations in the past 50 years, for starters – and what that means is that the avalanche of sand could go off at any time.

I'm not writing this to make any obvious point, or because I think this little essay here will change anything in the greater scheme of things. It won’t. But maybe I say something out loud that you’ve been thinking for a while, but haven’t really allowed yourself to dwell on for any length of time, for fear of where it would lead.

I write this to say it out aloud, or at least as “aloud” as a self-published Substack post permits:

We better fucking prepare. We better get done what needs to be done before it’s too late.

This is not “The End,” if there even is such a thing, but it is getting serious. Seriously serious.

Just today I thought that this must be the feeling people had when they knew a war was coming. This is what it must feel like to hear on the radio that enemy troops have crossed the border into our homeland, and the surreality of having to go outside to harvest some potatoes for dinner right afterwards like nothing fucking happened probably felt similarly eerie to what I’m feeling right now.

I know this because this is what we Germans have embedded in our cellular memory, part of the intergenerational trauma being passed on from grandparents, to our parents, to us; the fear of Tod und Verwüstung, of death and destruction, lingering in great-grandmother’s old bedroom. Sometimes, when we are still kids and our minds haven’t fully been reprogrammed yet, we can access this fear, feel a lighter version of it, weakened over the decades that have passed since.2

This is what it feels like when doom is impending. The enemy is almost at the gate, and we’ve heard the news of fortresses elsewhere that have already been flattened. Their names sound eerily familiar, places that some of us might have visited once, or maybe we know someone who lived there. Places like Lahaina (Hawaii), Lytton (Canada), Paradise (California), Cobargo (Australia), and many other towns and villages consumed by the raging flames.

Only this time we will not be facing an army. We will be facing waves as high as a house, gusts of wind strong enough to shove us aside, floods that rise faster than the ants can climb, and fires that blaze quicker than we can run. We will face a much more humbling opponent. We have unleashed the fury of our Great Mother herself.

We are at her mercy now.

By now even the most naïve people will have realized that there’s something the friendly evening news anchor hasn’t been telling them. Beneath the fake smile and the tailored suit, dread is creeping up his spine as well, at least if he has even a moderately keen mind. But for the moment, reality still resembles our memories of the last century closely enough to ignore the red flags – at least if we squint a little – so for many people it becomes psychologically easier to ignore and downplay those risks. Most of them haven’t had the time, the opportunity or the motivation to dive into the literature on climate change. Most of them can’t yet grasp the magnitude of what we have unleashed. The moral dilemma is this: shouldn’t we tell them? If we alone knew a war was coming, wouldn’t we warn our unsuspecting neighbors?

Further entrenching oneself in romantic notions of long bygone days ultimately does nothing to avert the problem, and those choosing to bury their heads in the sand will regret it bitterly as soon as hell breaks loose.

But this is not the time to throw away everything and go on one last bingeing spree, climaxing in a fatal overdose – we doomers are not whom the elites and their lackeys try to paint us as. Now is the time to get out there and plant trees, if that’s what the ecosystem you inhabit wants you to do. Plant them everywhere you can, and with great care, for one healthy tree is better than a hundred dead ones. And if some of them die in the next heat wave, plant them again. Plant as if your life depended on it, because in a way it does.

Now is the time to grow a garden, get a spade and rip up that lawn, compost your own shit, and try to grow as much food as possible, as long as that’s still feasible. This will not save us, we doomers acknowledge that, but it will absorb some of the shock and potentially ease the transition to whatever comes next. Supply chains are going to break3 long before our backyards become too dry to be cultivated, at least in most places. Cultivating things in California’s Central Valley will become impossible years before your small home garden, sparingly irrigated by rain water tanks around your house, will dry up.

Now is the time to acquire and build those rainwater tanks and catchments, at least if you live in an area where that will be necessary.

More importantly, now is the time to move out of the cities, which can become death traps in a matter of hours.4 Imagine a city like Bangkok next year, during the height of El Niño, or any year after: millions of people in sweltering heat, all cranking up their A/C and running their fans at maximum speed – until the electrical infrastructure suddenly collapses under the overload of appliances.

How many hours before people start dying?

Of course, many objections can be made to the previous paragraph. How should we even go about accomplishing this? Where will we go? What will we do? But those are all things we will have to figure out along the way, for better or worse.5 I don’t claim to have any solutions – I highly doubt there are any – but I have a few ideas and suggestions. To put it into slightly different terms: if we knew a war is coming, wouldn’t we prepare? Wouldn’t we choose to flee ahead of time? Wouldn’t we disregard traditions, customs and laws, and try to save ourselves anyway?

Admittedly, if enough people would actually attempt this (which most likely won’t be the case until it’s too late anyway), chaos would ensue. But chaos will ensue either way, and it has to start at some point. Why not at a point at which we still have some agency, at which there still is a tiny window of opportunity to dampen the impacts of the impending catastrophe, at least for some of us?

The pond is half full, so it’s now or never.

Now is the time to go out there and try to connect with the few people who are willing to look beyond the lies of the IPCC and the mass media. It’s time to get to know each other and remember that the common goal is more important than our minor differences in political opinion or who our favorite political theorist, talkshow host or thinker is. Anyone who wants to reduce reliance on industrial infrastructure and technology, increase local food systems resilience, rewild the land and themselves and learn practical skills is a potential ally – no matter which political party they support (if any!) or for whom they voted.

The system seems utterly unable to change, it is a speeding train on tracks that abruptly end in a massive concrete wall, and it can’t escape its predestined course. But we can. We have to.

The pond is half full.

The landing will not be soft, as my own lifestyle experiment has repeatedly shown, but we can still make it. We have to hurry, though, before the accelerating train is becoming too fast to ensure us a (relatively) safe landing.

We will have to reorganize, to try to replace those essential networks and institutions that the decaying system abandons as it shifts its focus from the increasingly insolvable problems of the real world to maintaining the illusion that we still inhabit the world of the last century.

The fucking IPCC has acknowledged as much when they said that we will have to halve emissions by 2030! It’s becoming clear now that we will probably not have halved emissions by then, but I predict that we will have lowered them, although it remains to be seen if that reduction is enough to outbalance the monstrous wildfires that will consume entire ecosystems by then.

To be fair, the lowering of emissions will not be voluntary, at least not in most cases. But emission curves run in parallel with the economy, and if the economy tanks, so does the greenhouse gas chart. I could point to the beginning of the Covid Pandemic, the 1970s energy crisis or the Orbis spike (the fatal downturn of the entire Native American economy) as examples, but I think the connection is obvious enough.

If there is anything most economists agree on right now, it is this: there’s some really difficult times ahead.

We need to start getting more comfortable with the bleak uncertainty, the existential dread that haunts us from time to time. We should not suppress it and we should not dwell on it, but we should acknowledge it, examine it, and see if maybe we can learn a bit about ourselves. For some people it helps sharing those feelings with others who feel in a similar way, although I wouldn't necessarily recommend visiting a therapist, because there’s a real chance he will tell you that the problem is in your head and prescribe you some of Huxley’s soma to make the pain go away.

We need to embrace the dread, so that it doesn’t paralyze us when it counts.

Even more: we need to spread this feeling.

“It’s only after we’ve lost everything that we're free to do anything.”

This line by Tyler Durden (from the movie Fight Club6) echoed through my mind for years.

There is a lot of truth to this unassuming quote, which seems so alien to people who spent their entire lives in the hypersecure environments civilization provides us with.

Adjusted to better suit the times we presently find ourselves in, the line might go as follows: It’s only after we realized that we will lose everything that we’re free to try anything to avoid the worst.

In addition, to make matters worse, the elites are desperate. Most of them don’t even understand what’s happening right now, why the world just doesn’t seem to continue conforming meekly to their will. They have lost their ability to foresee the future, as evidenced by the repeated mouth-gaping surprise at a majority of Britons voting for Brexit, Trump being elected president, Putin invading Ukraine, and at any time a new climate catastrophe unfolds (that certain scientist have warned us about for decades).

I’m genuinely afraid of what will happen when the elites really start panicking. Jem Bendell warns us in his latest book, Breaking Together: A Freedom-Loving Response to Collapse, about the rise of eco-authoritarianism: think Covid restrictions, arbitrary symbolic rules that supposedly show how serious the elites are taking this problem, and concomitant emergency powers – multiplied by a factor of ten. All that in the name of “saving the world” or, for those more honest among them, “saving civilization.”

However they phrase it, it’s a battle they can’t win. But they will try everything in their might, and they will stop at nothing.

I fear the day will come that the sky changes its color, and I dread the day we will see the mountains around us burn. Chances that those two things will happen are good enough – it’s more a question of when, not if.

That chart depicting the scale of Canada’s wildfires leads me to believe I have to reset my schedule.

Back in 2018, when I first read T.C. Boyle’s eerie work of climate fiction, A Friend of the Earth, I didn’t disagree with the overall picture he painted.7 I just wasn’t sure about the timeline he presents. The book is set in the year 2025, and the world already looks so apocalyptic that I found it hard to believe that in a mere seven years the face of the Earth would change that much.

After this summer, I’m not so sure anymore.

Admittedly, it’s not going to be as bad and as dramatic as depicted in the novel, but we’ll be pretty close.

I have no idea how to end this essay, because I feel like it doesn’t have an end. It’s the sequel to a whole series of similar pieces I write during the hopeless phases of the Hope-Despair Cycle, and the process described herein hasn’t ended.

It has barely begun.

And that’s what worries me most.

I write stuff like the above in my free time, when I’m not tending the piece of land we’re rewilding here at Feun Foo. As a subsistence farmer by profession I don’t have a regular income, so if you have a few bucks to spare please consider supporting my work with a small donation:

If you want to support our project on a regular basis, you can become a Patron for as little as $1 per month - cheaper than a paid subscription!

This is actually a quote from the future. I don't know from whom exactly, but I do know that plenty of people will start saying this really soon – even more than right now.

One might say we can still “feel the Spirit of the Land,” if one is so inclined.

For us mere mortals, at least – presumably DoorDash will continue to drone-deliver GMO-KFC to Elon Musk and his army of clones in his future fortress below the tar sands for decades (another reference to Arnold’s podcast Fight Like An Animal – seriously, give it a try!).

I don’t mean to suggest that the countryside is necessarily “safe” – that depends on too many factors to be able to generalize – but the sheer concentration of people in cities makes them the most vulnerable. Historically, fleeing to the countryside has been a common response to the threat of war, and urban exodus does make some sense as a response to severe disruptions due to climate change. It’s not the “ultimate solution,” but there is no such thing.

In much of the “developing” world, people still have relatives in the countryside, and there are still plenty of smallholder farmers – so this urban exodus would be, as I’ve suggested before, easier for people in “developing” nations than for those who live in the “developed” world. Of course, anywhere in the world it becomes the responsibility of those with land, especially those with a lot of land, to try to accommodate climate refugees. Furthermore, corporate landowners have to be forcibly disowned and company land will have to be squatted. We here at Feun Foo have recently began thinking about this a lot, but due to the fact that we don’t have a lot of land we will only ever be able to accommodate two or three people.

I know Fight Club isn’t as cool as it was at the time, and I will probably have to defend myself against criticism in the comments, but let me anticipate some criticism by pointing out that Fight Club is many things, but not “fascist.” If that’s your claim, look up what that word means and think again. I also never thought that Fight Club was “promoting toxic masculinity” – for me it seemed blatantly obvious that the whole “we don't need women anymore” talk was a parody on the overt machoism displayed by Tyler Durden and his friends.

If you didn't read it yet, I highly recommend it.

wonderful and sobering piece.