Why I stopped saving the world

…and why you should, too --- [Estimated reading time: 40 min.]

Throughout this essay, I will juggle with different meanings for the term “world.” Sometimes I will mean “the human-made world” (a.k.a. civilization), sometimes “the entire global biosphere,” yet other times it will be more along the lines of “the things I see when I leave my garden,” or “what ‘normal’ people consider important.” It’s probably obvious which one I mean in each instance, although I hope the variability of its definition – to the point of utter meaninglessness – becomes obvious in the process.

"The world doesn't need us to save it, it needs us to leave it alone."

Those words by Daniel Quinn were on my mind for months after I first read The Story of B, the book that changed my life like no other, back in 2015. The more I thought about it, the more it made sense.

About decade ago, I set out on an adventure of trying to learn basic life skills that would allow me to achieve a greater degree of self-sufficiency and reduce my ecological footprint, thinking that all of us living in “developed” countries should do this in order to "save the world" – which of course we have to, because otherwise, what will happen to her? "Save the world" is a slogan you see around a lot when you grow up in modern society. It's the right thing to do, you're told. It’s a noble goal (but it won’t pay the bills!), warns your teacher. It’s our mission, our commitment, proclaims corporate advertising. But the big question is: how? By changing your light bulbs? Donating to a charity? Investing in “renewables”? Taking shorter showers? Shopping consciously? Having a few solar panels installed on your roof? Buying a new (but electric) car?

Or by gluing yourself to a road?

It’s certainly no easy thing to do, but when I was fresh out of school – a decade before a global pandemic crippled the economy, massive wildfires consumed entire regions, microplastics and PFAS were found in the rain water and bodies of all living beings, and extreme weather events devastated crops and livelihoods on an unprecedented scale – everything seemed possible. Back in the days we still had hope. We still had reason to hope. Or so we thought. You grow up in a middle-class family in one of the wealthiest countries in Europe, and you think that you can “save the world,” if that's your thing. Hell, you can do anything!

But soon enough, reality knocks you out of the sky. You’re too busy to “save the world” because now you have to work in order to stay alive. You have to make ends meet, take responsibility for things you’d rather not, and spend plenty of time doing things you didn’t even know were necessary, things that are not really all that meaningful, let alone pleasurable. In the evenings, you come home so exhausted from work that rolling a joint and vegetating in front of your computer screen for a few hours are the only thing you can muster. How should we even start to approach the monumental task of “saving the whole world?”

Under further scrutiny, the slogan starts to look about as meaningful as Obama’s extremely creative campaign slogan, “Change.” Do we really think we have the power to single-handedly “save the entire world?” Is this something that’s even possible to achieve? But we can surely destroy the world, so why can’t we save it? And what does “save” even mean? Save it from whom, and for whom – for future generations? From what, and for what – for later?

Many times, what people mean when they say “save the world” is “save the world as a human habitat.” But humans have inhabited this planet during times of climatic extremes before, so maybe the human habitat itself is not even under direct threat, although at no point during our three-million-year existence have we encountered similarly high levels of CO2, which is at least somewhat concerning. Human habitat will likely be drastically reduced if “Business As Usual” is allowed to continue for a few more years, but it probably won’t disappear entirely. Hence, to “save the world” in this context takes on the meaning of “saving the world as it is right now,” as one gigantic playground for humans, which is akin to saying “change nothing and leave it as it is, just let the show continue for a bit longer.” Can that really be considered “saving”? Is the world safe right now?

More importantly, when people say that they want to “save the world,” this usually also means “save the world while causing me the least possible inconvenience,” or “save (the current high-impact consumer lifestyle without destroying) the world,” which for most people translates to “meh, but there better be Netflix, global trade and travel, and stocked supermarket shelves.” Otherwise, if we acknowledge that those things are mutually exclusive, people who want to “save the world” would have already drastically reduced consumption of all but the utmost essentials, cut down on all aspects of life that are not absolutely necessary for survival, and grow or forage as much of their food as anyhow possible.

In short, they’d live a lot like me.

The problem is, I don’t see many people living like me. Why?

I know, this might sound self-righteous, and I’m well aware that most people don’t have the privileges I do (most importantly, no noteworthy debt and a hectare of land). But it's better to use one’s privilege to reduce or even reverse one’s environmental impact and spearhead an alternative lifestyle, culture and subsistence mode than to be some regular guy living an average life in a city somewhere in the “developed world” – or not? And even the ones that do have the privileges necessary to change their lifestyle – I don’t see them trying. Not even a fraction of them. Why? Because most of them are either blissfully unaware of the true scope of the calamity looming overhead, or high on that “hopium of the people,” hallucinating bright-green utopias with flying cars powered by hydrogen fuel cells, electric bullet trains crisscrossing the globe, and distant space colonies mining asteroids. Or they simply don’t care.

Those folks are in for a surprise – and not one of the good ones.

The facts are: we need to phase out fossil fuels now (as in “today!”) if we want to avoid “catastrophic climate change” (which means climatic changes severe enough to lead to the collapse of global civilization). Climate change alone, whether man-made nor not, has happened before, true. Of course, what we are currently experiencing is happening much faster, but it’s still no comet or volcanic eruption, at least not yet. It’s tragic, but it’s not necessarily the worst thing. The world has survived much worse, without anyone saving it. It could always be worse, yes – but that’s of little consolation to us, being alive at this point in history. Moreover, it’s no valid excuse we can tell our children. Even I get angry when older people – the infamous “boomers” – tell me this, because they will have comfortably died of old age when the real trouble starts, whereas I will have to live through it. Its easy to say those things, knowing that oneself will not experience them. “The world will be fine,” they say, “you can’t halt the inevitable.” But shouldn’t we at least try? Wouldn’t you, if you were younger? “Nature will recover eventually.” Yes, but what about those that have to survive in the meantime?

Civilized humans actively and deliberately compromise the habitat of other species, turn diverse ecosystems into literal deserts through agriculture, mining, drilling, industrial development, urban sprawl, and a wide range of other activities we consider “necessary,” although humans have survived and thrived for hundreds of thousands of years without them – none of those things were “necessary” for the vast majority of the time our species exists, yet we continuously choose to perpetuate each consecutive step of escalation.

If it would only be climate change, it might not even be too bad. But there is no more natural habitat, no more migration corridors, so extinctions go up. While we can’t stop this anymore, we could at least slow it down, to give all the non-humans we share this planet with a chance to adapt. But that’s not what’s happening. We consistently choose some humans (civilized humans, not indigenous humans; rich humans, not poor humans) over all other life. No, if we really wanted to slow down climate change and the current Mass Extinction Event, we all would have to make drastic changes to how we live our lives, and find a way to force those above us in the hierarchy to do the same. We would have to make do with less, which is utterly unthinkable to most, despite by the fact that “less” in this case could also mean less stress, less pollution, less destruction, less noise, less illness and less existential worries.

Oh, and less extinction, of course.

But since nobody wants to reduce anything, at the very least their hard-earned standard of living and whatever “comforts” and ‘pay-to-play’ pleasures they can afford, this would have to be done by either waiting for a wonder – with rather low chances of success – or by replacing fossil energy with what’s being commonly called “renewable” (or even “green”) energy.

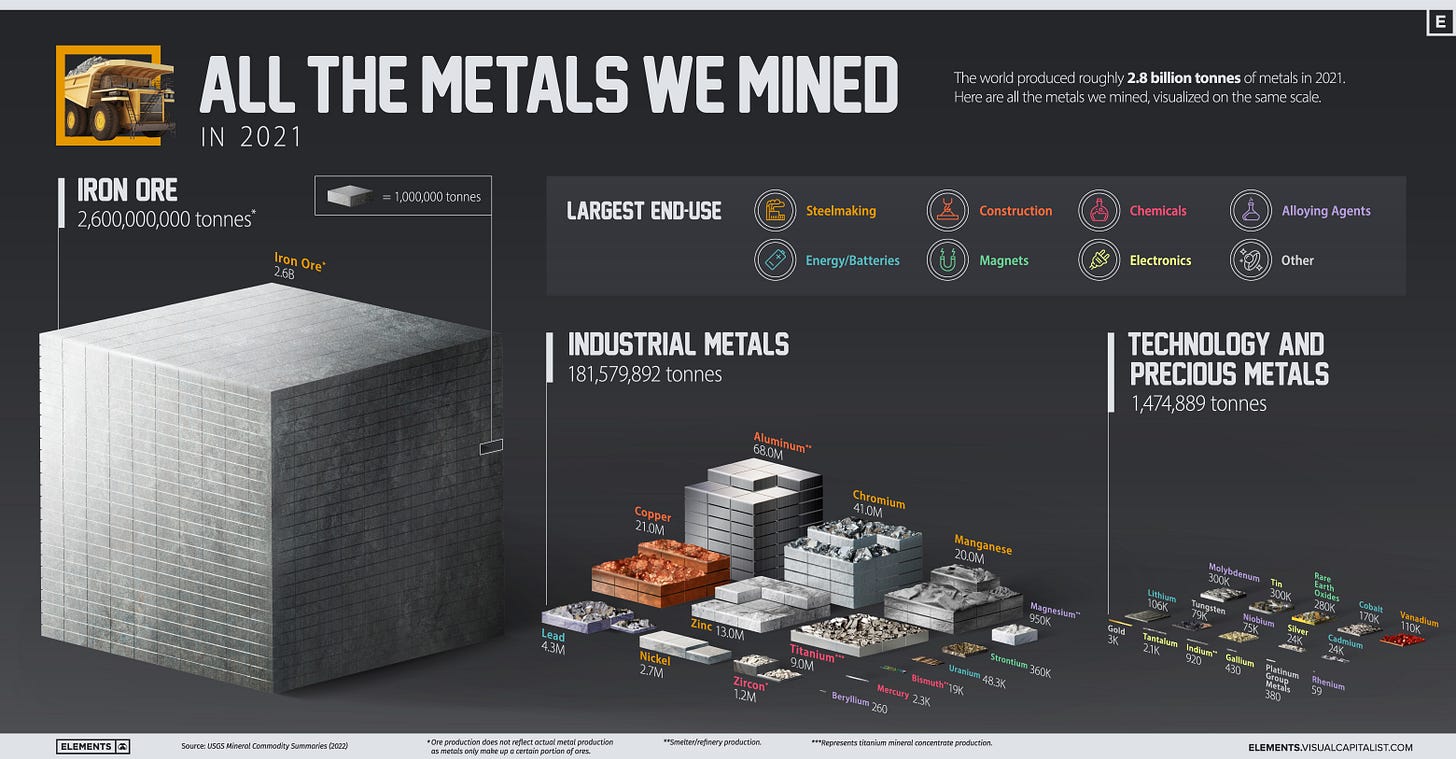

The problem is: there are simply not enough resources left in the world. I wrote exactly this back in 2018 as a response to a viral talk by technophile Jeremy Rifkin (who seriously proposed a “third industrial revolution” – as if we didn’t have enough of those already!), and a recent presentation by mining engineer and Associate Professor of Geometallurgy Simon Michaux (that you really should watch) has again proven this fact. There are not enough metals to build even a single generation of so-called “renewables,” not even a fraction of it – plus, even if we had the resources (which we don’t), it would take much more time than we ever had: several decades is a good estimate given by Michaux, who damn sure knows what he’s talking about. Civilization will have collapsed due to a number of other stressors long before that time.

Yet leaders tell us we will halve emissions until 2030. We have to, if we want to avoid runaway climate change. That’s six and a half years from now.1

I'll tell you what will happen. Leaders simply don't know yet that there are not enough resources, as the presentation by Prof. Michaux shows beyond any doubt. In the Q&A session after the presentation, Michaux also tells us a few anecdotes of what happened when he talked to politicians and other leaders about the issue: the reactions ranged from disbelief (by people with no expertise in the field, I’d like to emphasize), over anger, statements amounting to "you've been a naughty boy, now please stop doing this," to simply telling him that his findings are too negative, and he should come back with a “solution,” something that inspires hope (as someone reporting directly to the House of Lords in the UK basically told him).

But let me rephrase this right quick:

Our own leaders have no idea of the extent of the catastrophe unfolding.

They haven't read John Gowdy’s eye-opening essay showing beyond the shadow of a doubt that agriculture will soon simply not be possible anymore because of climate change, so the entire question was never if civilization collapses, but when.

It will collapse, let there be no doubt.

They haven’t read the 50-year update of the famous 1972 report Limits to Growth, which again verified that we are on the path to collapse in the early 2030s, partly due to crucial resources running out.

They haven't yet read Simon Michaux' latest paper, on which the above-mentioned presentation is based, which validates the update to Limits to Growth and shows in clear detail and with the governments' own numbers (from their own Geological Surveys) that there are not enough metals and minerals to build the “renewable” energy infrastructure that would be required to phase out fossil fuels. So far, nobody has been able to refute his basic conclusions,2 but people will try to discredit him with all their might. He is destroying an illusion, the illusion, the one that keeps us all toiling and shopping and bingeing and consuming, while hoping that whatever storm is brewing on the horizon will not arrive until we’re dead. What his findings show is that renewables can never phase out even a fraction of the fossil fuels we’re so merrily burning through right now.

So people won't phase them out.

Remember, it is not a given that we phase out fossil fuels. There are already people opposing it, and many more will soon join their ranks as problems intensify and people yearn for the comfort of past times where life was easier and felt more secure.

As life slowly becomes unbearable – even for what remains of the middle class – society will experience a fracturing that lets US-American polarization of society appear like a friendly game of cops and robbers.

There will be a large group of people, perhaps as much as half of the population (depending on the country in question), who will not be ready to compromise their energy-intensive standard of living. If that means continuing to burn fossil fuels, then so be it. They don't care about "the environment", because to them, that's “out there.” They care first and foremost about the short term; about themselves, their family and immediate community, and the system that has housed fed and clothed them for their entire lives. Abstractions like climate change or biodiversity collapse are simply a bit too much to comprehend for a lot of us. Not everyone's brain is able to conceptualize hyperobjects.

So they will continue to “drill, baby, drill,” because it keeps the lights on and the engines running. Most “developed” nations happen to be located in temperate climate zones, and it would be increasingly difficult to make it through the winters without burning fossil fuels, so phasing them out would be akin to a death sentence in the eyes of many first-world citizens – which is why they won't accept it. If renewables can't save them, they will just continue to burn fossil fuels.

Now you might interject that this is a rather pessimistic view, and ask how I can be so sure of that.

First of all, with everything I’ve said so far, and everything that’s happening around us, how can you not be sure? Admittedly, I can’t accurately predict the future, but I never claimed that I can. I am talking about probabilities, not prophecies, and they are informed by a rapidly growing body of literature on a wide range of topics – and observations in the real world, out there, not in some W.E.I.R.D. echo chamber. I live in the countryside of a rapidly developing country in Southeast Asia, and things are not looking good here. Many Westerners don’t know this, or at least don’t know the true scope of what’s happening here. A 2010 report for the National Intelligence Council predicts that one or more nation states in Southeast Asia will have collapsed until 2030, and the same report concludes that “Southeast Asia faces a greater threat from existing manmade environmental challenges than from climate change to 2030 [Emphasis mine].”

Right here, right now, civilized humans’ activity is far more dangerous and destructive than climate change.

Let that sink in.

Those living in the Western world, the so-called “first world,” should be under no illusion here: it might feel like people are slowly “waking up” to what has been called the “Century of Decline,” but for every one person who is realizing the severity of the situation we’re in you have a few dozen people in so-called “second” and “third world” countries who finally want their piece of the pie. It has been promised to them for decades, by teachers, news anchors and politicians, and now they are told to skip their trip to techie wonderland and go back to what their ancestors so painstakingly did for the past few centuries?

No. They will press forward with unprecedented fervor. They won’t accept decline and many will deny collapse even as it stares right in their faces, which it already does in many parts of the “developing” world. The party who won the Thai elections last month, the aptly named Move Forward Party, didn’t even mention climate change (or the environment!) on the pamphlets they handed out at the local market. After their victory, the trending hashtag on social media was #ได้กลิ่นความเจริญ – “I smell progress.”

If they have to burn coal and gas to get there, so be it. It’s not them who caused global warming in the first place, they will say, so who is the “first world” to deny them their right to extract and pollute their way to prosperity?

In a debate with a guest visiting our farm, I was recently told that air quality actually increases in many parts of Europe - well, hell, might that be because you've simply outsourced the most pollutive industrial processes, and export most of your waste to poor countries and call it “recycling”?

Never forget that if you live in a W.E.I.R.D. country your perception of reality is tainted by rose-colored glasses that most people are not even aware they’re wearing. But don’t let this illusion of safety and comfort fool you – climate change is coming for all of us, and it doesn’t care how much money you throw at it.

They will try to find a less pollutive and destructive way to continue growing the economy, sure, but ultimately they can’t succeed. No matter how much you disagree with the geological realities we’re facing, you can’t just summon new minerals into existence. So they will go with what has worked so far – burning fossil fuels – while simultaneously making up excuses about the importance of growth and vague promises of carbon offsets in some place that’s not their own, somewhen in the future.

“As our crisis deepens, those tidy emissions curves that plummet to ‘Net Zero’ by 2050 require more and more totally speculative carbon sequestration - and they even do so without sacrificing consumer choice. If we want to continue to undo the conditions that make life possible for a little while longer, we can take the yellow curve and fix the damage later by waving the negative emissions wand a little harder.” - Arnold Schroder, Fight Like An Animal

That's the real face of the Western world, behind their charade of climate summits and COP conferences.

The reality is this: they will continue to burn fossil fuels as soon as the slightest inconveniences are on the horizon. How I know this? Because that's exactly what Germany did last winter.

Yes, the country that magically managed to become a major European powerhouse and catapult itself to the forefront of global politics after losing two world wars, the country that has spent the better part of the last two decades loudly bragging about how much it loves and cares for the environment and poor brown people (while selling guns and tanks to everyone waving a wad of money), advertising hydro and solar and introducing terms like Energiewende into the globalist vocabulary.

As soon as it became known that they might experience the slightest sliver of discomfort due to the war in Ukraine and concomitant gas shortages, they fired the old, long-phased-out and forgotten coal-fired power plants back up.

So much for umweltfreundlich, Herr Deutschland.

This example suffices to show what we all know deep down: people will not voluntarily reduce their energy consumption. What about large cities in tropical and sub-tropical climates? You tell me: Who is going to tell the people in Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur, Mumbai, Kinshasa, Nairobi, São Paulo and Mexico City to turn down their A/C during the next El Niño?

No, this is not what the masses want. And by the time they change their mind – if they change their mind – it will be too late.

This world does not want to be saved, I say.

Let it go to hell then.

But let’s assume my predictions are right so far. Let’s think about what happens next. People continue to gleefully burn as much and as many fossil fuels as they want. But for how long is that going to work before those ugly, annoying limits come into sight again?

In no time, oil will get expensive. Partly this will happen because of geopolitics (which also means an increased risk of a major war, which alone I could write a few more somber paragraphs about), partly because of accessibility, feasibility and profitability, and partly because there is simply not much left to extract. Don’t get me wrong: there’s plenty of oil left, and plenty of other fossil fuels as well, but the real question is if it is viable to develop them.

All of the easily accessible stuff is gone.

This is true for all high-grade ores as well.

Gone are the days where you could just drill a hole and oil would come spurting out.

Now I could venture into calculating whatever the latest numbers (brought to you by no other than BP!) say we have left, but this would be a pointless exercise for many different reasons. First of all, do we really expect them to tell us the truth? Really? Why would they? Have they historically told us the truth?

Would they tell us the truth even if that would mean the almost immediate end of their business, as stakeholders would rush to cash out?

If I would dive into those numbers, the result would show that there is enough oil left for another 50 years or so – “at current production levels,” which might mean a mere 20 or 30 years if we account for the steady increase in oil production that just doesn’t seem to abate. But what this peculiar turn of phrase means is that we, mere mortals, have no idea how long it will last, and Big Oil is unwilling to tell us, so they just say something along the lines of “don’t worry, it won’t be your problem.”3 As Nate Hagens pointed out in his interview with petroleum geologist Arthur Berman, the Peak Oil community has been obsessed with trying to predict the exact point in time at which global oil production peaks, when in fact other things are much more important (such as: how the hell do we prepare for the slide down Hubbert’s bell curve?).

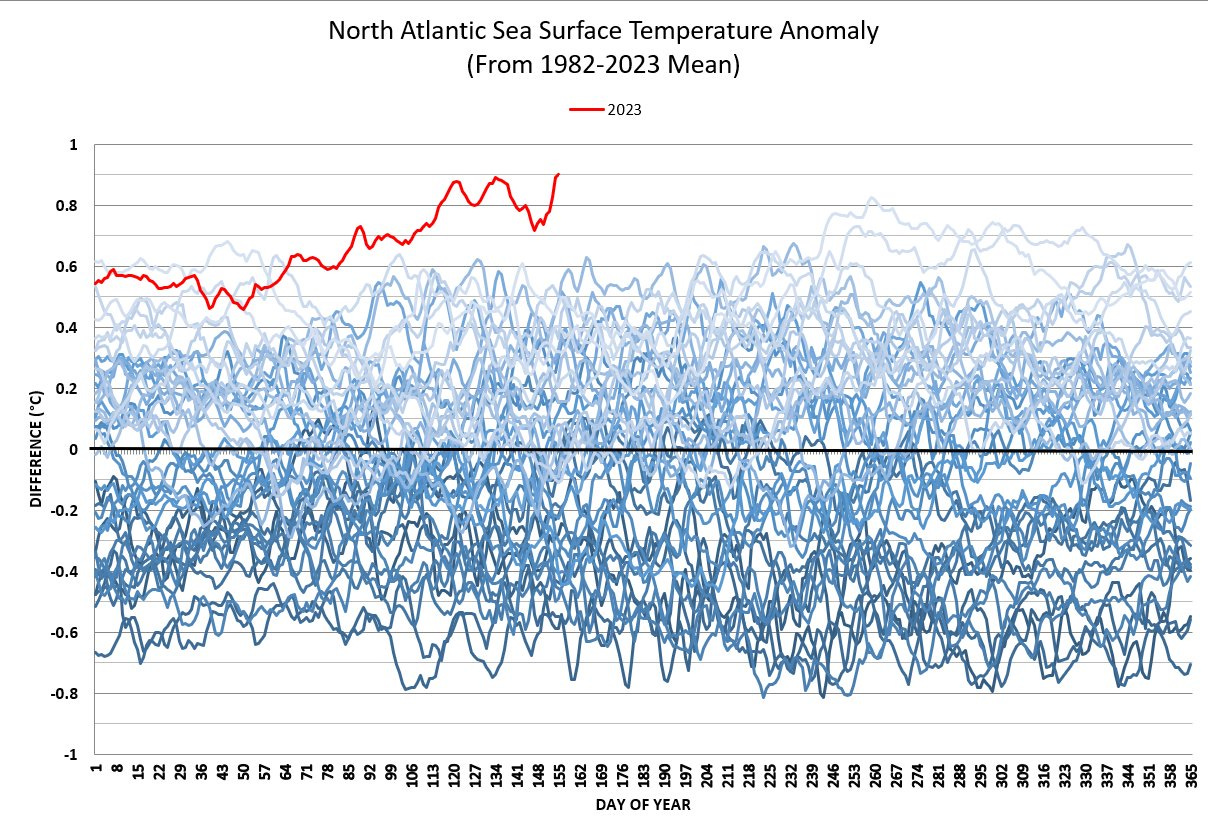

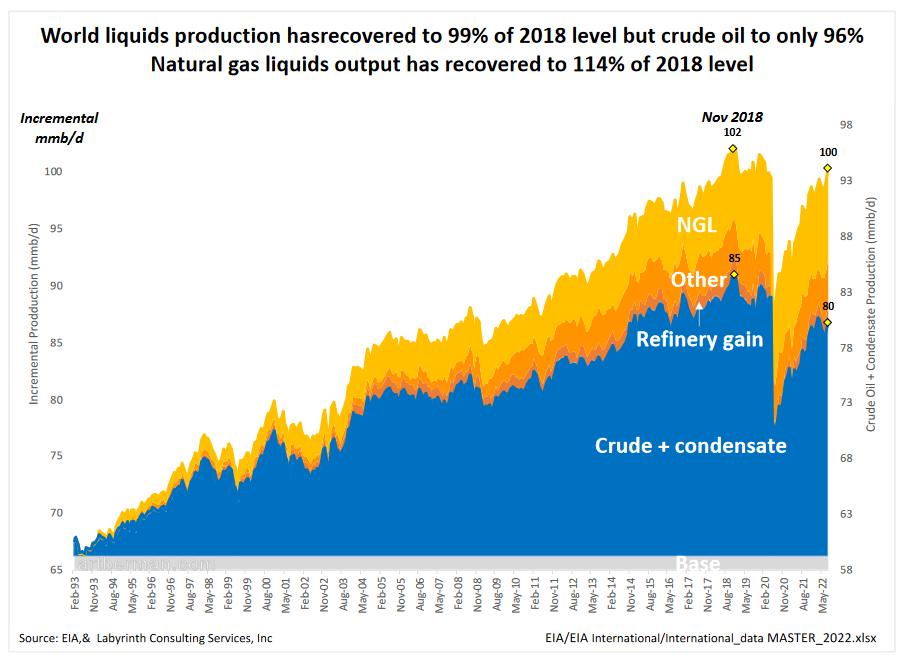

The thing is, as Berman and Michaux have shown, that production is already decreasing in all but five countries (the US, Canada, United Arab Emirates, Iraq and the Russian Federation; if the US and Iraq would be excluded, world oil production would have peaked in 2016), and even the US numbers are skewed (about 30 percent of what’s considered oil production in the US is actually NGL, natural gas liquids, which isn’t as versatile and energy-dense as crude oil), which led Hagens to conclude that “the real Peak Oil” might have happened in November 2018.

Whenever “Peak Oil” happened, the real picture is a lot more complex.

There are more and more people who say that the reason the elites are pushing “renewables” with such fervor is that they know more about the reality of Peak Oil than they care to admit. They see that fossil fuels are in decline, that simply burning more of them will soon hit other limits, due to cost and availability. In the absence of evidence this could easily be discounted as a mere conspiracy theory, but is it really that absurd?

Another thing that will happen as a consequence is that normal people will spend more and more of their income on gasoline. The government might try to substitute it as long as possible to avoid unrest, but that is not without its own risk, namely the government in question going bankrupt, or severely defunding crucial other sectors. Soon enough, gasoline will become a luxury product. People will fight over it, steal it, illegally refine it, and even trade it on the black market as a high-value commodity.

Now that both renewables nor fossil energy will save us, what will?

Expect last-minute, desperate attempts at geo-engineering as the world spins off course and slowly becomes “unsavable.” Geoengineering is the techies’, capitalists’, economists’ and longtermist’s way of “saving the world” – reengineer the aspect that causes problems. While this approach may work well with an engine, a factory or a computer program, it does not work with hyperobjects too complex to understand for our primate brains. People will use AI in a fanatical effort to employ a “higher form of consciousness” that’s supposedly superior to our human intellect, but AI has its own inherent limitations, which are often eerily similar to our own. Moreover, AI itself poses a real threat to industrial civilization. White-collar workers are already starting to lose their jobs to AI, and the radical restructuring of an already highly unstable society plagued by a multitude of converging crises is a powder keg suspended over a fire.

Things are starting to look bleak for this society.

Is there any way we can still “save the world,” with everything that’s going on around us?

To give a recent example of the futility of thinking there is anything we can do to stop what’s coming and “save the world,” let me briefly recount our experience writing and presenting a reforestation proposal aimed at reforesting the most severely degraded part of the Wildlife Sanctuary next to our land, which was devastated by a forest fire two decades ago and has since been overgrown by running bamboo. We had thought about starting a reforestation project ever since we moved here, but in the first five years, we simply had enough on our hands working in our own garden.

So we finally wrote our proposal earlier this year and presented it to the local authorities. We had the best intentions, but again and again we were reminded of where exactly we stand in the social hierarchy.

“How are we even supposed to know how to reforest a piece of land,” we were asked by a local Foundation4 involved in reforestation efforts, “if we didn't study forest ecology, or worked a job in a field that has to do with forestry?”

We read plenty of books on those topics, we retorted, and told of the success we had on our own land. But apparently that doesn't count. If you’re not a trained and certified professional, you shouldn’t even open your mouth with an opinion, and even if some “expert” would decide to reforest the piece of land in question, we would only be qualified to “cut grass and water trees,” we were told - by someone whose job it is to aid reforestation projects.

The Foundation ended up advising us to team up with state-owned oil company PTT, which is apparently looking for places to reforest in oder to greenwash their image.

Teaming up with an oil company is our best shot at “saving the world.”

We talked to a few villagers and told them about the broad outline of our plan (in varying detail), and time and again we were told that the Forest Rangers (who report to the Royal Forest Department and are responsible for all protected areas) are actually quite content with the degraded state of the land, since it means they have much less work patrolling. No trees to log, no animals to poach – which means that they get their government salary without having to do much work. One of the guys who told us this is a relative of someone working in the Rangers’ main office, so I guess there must be at least some truth to that.

Any reforestation project would have to be overseen by them, so they’d have more work. The woman from the Restoration Foundation who counseled us in the beginning also didn’t have anything good to say about the Rangers in general: she said “they just sit in their office all day and ‘eat their salary’” and “there’s always complications when you work with the Rangers.” Okay, but those are the people supposed to protect and care for the country’s forests, right?

What would they have to lose, what risks would they have to take to let us reforest a few hectares of land?

We would do all the work, we assured them, and all we would expect them to do is to periodically pay us a visit to see if everything is going according to plan. The head of the local branch of the Forest Department failed to visit us last month, as he had previously promised, and didn’t respond to our emails.

Everyone tells you to “plant trees to save the world” – and this is what happens when you actually try.

The entire system is stuck in the 20th century. It's too rigid, too stuck in the quagmire of bureaucracy, and thus not able to adapt fast enough to a rapidly changing world. Anyone with a bit of common sense would have given us approval, especially if they would have read the proposal carefully and understood we harbor no ill intentions.

This system has become too complex for its own good, and now it is unable to change. It can only move in one direction, and that is forwards – more complexity, more development, more, more, more! – otherwise it would cease being “the system.”

What’s really needed is a de-complexification, a Great Simplification so to speak, and since the system won't do this voluntarily, the only way out is (apart from a global revolution, maybe – which seems rather unlikely right now) collapse.

After all, the very definition of collapse is “a sudden and drastic reduction in complexity.”

But this is the worst-case scenario for those in power, so expect them to try everything to stop it or slow it down. They will show their true faces, they will cling to their power with all their might, and it will get really ugly once the billionaires fund their own private militias of elite mercenaries and start financing assassinations and abductions to pursue their goals and eliminate everyone who stands in the way. The only thing we have standing against them is our sheer numbers. They are not even “the 1%,” as they are often called, they are a fraction of one percent, and if only a third of the other 99.99 percent unite, the elites wouldn't stand a chance – in theory.

The Atlantic just published an article concluding that a “violent revolution” may be needed to overthrow the elites, and we’ll see how that goes.

I’m glad to live far away from the epicenters of civilization. But is it far enough away?

When contemplating the bigger picture, our reforestation efforts seem ridiculously futile. With everything happening, does it even matter if we plant a few trees?

Often, it feels like my wife Karn and I are cycling through the phases of the Circle of Hope and Despair. We watch online conferences about agroecology, read books by indigenous people, and talk to friends who are doing their best to “save the world,” which raises our hopes. Once hope has reached a critical threshold, we decide that now it’s time to go out and do something – meet people, educate folks, raise awareness, shout from the rooftops, anything – but then we are painfully reminded that most people are stupid, ignorant assholes, and don’t even care about what we have to say, no matter how carefully and thoughtfully we try to present it. This in turn causes us to lose all hope, curse society and the ignorant dupes and dullards it is comprised of, and conclude that from now on, we shall only stay on the farm, the only place where things still seem to get better, not worse. This is followed by an intense period of gardening and spending almost all of our time here, hands in the soil, during which we have plenty of free time to read and discuss, and we start having some really great ideas together.

And then the cycle starts again.

Karn says that she doesn’t understand why we Westerners always want to “save the world.” She never wanted to “save the world,” she never even thought about “saving the world,” because, as she says, “I’m only one person, how can I save the whole world?” And there's a profound truth hidden there.

It’s a Western thing.

The truth is, we really can't do it. It’s too much responsibility. It’s not even our job or our duty. We're not gods, or billionaires, or politicians, or celebrities, or anyone else people pay attention to. We are subsistence farmers living in conditions that would shock most readers of this essay.

But we can try to save the people around us, the place we inhabit, and its myriad other inhabitants. As our reforestation proposal so clearly showed: it’s an uphill battle, one that we’re more likely to lose than to win, but at least we can try.

We can build community gardens, hold free classes on herbalism, bushcraft, and permaculture. We can create networks of mutual aid to replace the neglected infrastructure of a civilization on its deathbed. Or, better, we could. If people would see the value in it. This might increasingly be the case in the Western Fortress, but it is not the case in most parts of the “developing” world.

As a desperate measure to prepare for the coming years of climatic instability, we have started planting as many drought- and flood-resistant staple foods as we can fit into our garden – since nobody else in the village cares to prepare, the sole burden rests on our shoulders. We most definitely can’t “save the world,” but can we even save our village?

The only sliver of hope that remains is that, as a society, we’re somehow able to reach a “collapse-awareness” tipping point: a critical mass has to acknowledge that all the dread and despair we are currently experiencing are symptoms of the collapse of global civilization and a way of life that we will have to abandon if we want to survive the coming decades. We have to accept our fate, and see what we do from there. To achieve this, we need to stop believing that politicians and other so-called “leaders” will save us – they won't. They don't even know what's going on, since they themselves are trapped in an echo chamber of paid advisers and yes-men whose careers depend on telling those “leaders” what they want to hear.

We have to prepare. We have to cease working for a system that doesn't take care of us, and to try to replace this system with something that does. If they don't even want to pay us living wages we have to stop working for them, and try to make sure that others can do the same.

Only if people know in their hearts that the world can’t be saved will they be desperate enough to accept real solutions.

Disastrous news come thick and fast these days, and there is no escaping the implications anymore. Anybody who tells me that all of the problems this society currently faces will be solved before they become positive feedback loops can go to hell. We don’t inhabit the same world. Although, strangely, I don’t feel much at home in this world anymore lately. It’s not the world I grow up in, not the world I was prepared for, and it’s definitely not the world I signed up for. “The Collapse of Global Civilization has begun,” I wrote six years ago. Today, after a two-year pandemic, raging inflation, a looming economic recession, the start of a new war with global implications, and the steadily increasing terror that climate change unleashes around the world this is clearer than ever before. In the three decades after the first climate summit, emissions have continued to rise exacerbated. In my lifetime, half of the oil that's ever been extracted was burned, and plastic consumption has quadrupled in those vanishingly few revolutions of the world around the sun.

Rainwater is not safe to drink anymore, they say. The most precious gift of Nature, this gentle lifeblood of the world, now slowly poisons you and all other living beings, all over the world.

Think about that.

It's too late, I say to myself. The world can't be saved.

Back in 2017, when I wrote that provocative article about collapse, I was expecting fervent pushback. Yet the feedback I got was almost entirely positive, with many people writing me to tell me that I put into words what they’ve been feeling for a long time. Until this day, none of my articles and essays had a similar reach.

The thing is this: I detailed all major aspects that are currently exacerbating the collapse of this civilization, but the one I didn’t anticipate was a global pandemic. I half-heartedly wrote about the risk of pollution, antibiotic resistance and declining public health, but I simply did not consider that a global pandemic would be the first shockwave felt throughout society, the first crystal-clear indicator that the inevitable decline of the global Empire of Money has started, that the end of the Reign of Cities has been set in motion. At the time I was sure that we would feel resource scarcity and concomitant disruptions to the supply chain long before anything else, which at least partially came true when we consider the chip shortage slowing industrial output worldwide that happened simultaneously, in part caused by the disruption to daily life and supply chains that the pandemic posed. But the first big domino to fall was a pandemic, not resource scarcity.

I was wrong.

This begs the question: what else did I miss? What other aspects could suddenly start causing severe disruptions to daily life, without anyone really anticipating them?

Now, six years later, how can we still continue to pretend we're not there yet? How can we tell ourselves that what’s happening around us right now is not collapse?

Once a month, I hold a five-hour video meeting with my family. And what are the topics we talk about these days? Irregular flowering cycles and rainfall patterns, mega-droughts, the collapse of insect populations, PFAS (called “forever chemicals”) in the rain, microplastics in the air, mothers giving birth to black placentas because of wildfire smoke, skies orange because of wildfires and haze so thick that it hurts to breathe, mountaintops that are removed to access resources, topsoil scraped away to make new orchards, forests bulldozed and vegetation burned to clear more land, all in a never-ending death spiral towards the abyss – “man-made horrors beyond comprehension,” beginning to be felt in our everyday lives.

How exactly are we not yet waist-deep in collapse?

My mom says that one of the worst things for her is the despair she feels when she sees little children. What world do we leave them? What horrors will they see in their lifetime?

This is collapse.

We’re living through it, right now, although most of us haven’t realized it yet. Once it becomes undeniable, once everybody starts feeling the disruptions to business as usual, once even the leaders start to admit it, you’ll hear people say things that sound eerily like what they said at the beginning of the pandemic:

“I would have never thought that I’d see something like this in my lifetime!”

“It feels so unreal, like something from a movie!”

On a different note: has anything changed substantially in the years since we were children, in the cities and in our everyday life? Where is the high-tech future we grew up believing in? The newfound leisure due to automation, the drone deliveries, the flying cars, the robots doing the dishes for us? Where are the space colonies and the asteroid mines? When, if ever, will they materialize? Is there even enough time? Was there ever?

Ask yourself the following: how much has technology impacted your life in a positive way, and how much in a negative way? The hard truth is: they have promised a lot, but delivered little. The constant upward trend we were promised failed to materialize for anybody but the most privileged members of this society, and if you disagree with this statement, it means you’re one of the latter. For the rest of us, life hasn’t changed for the better. Utopia has turned into Dystopia in our own lifetimes.

I tried to raise awareness and warn others with facts, studies, numbers and data back in 2017, and it clearly didn’t work as well as I hoped. Most people continue to be hopelessly unaware, especially outside of the “developed world.”

With this little essay here, I want to try a different approach. I attempt to appeal to feelings and observations that everyone can make, to draw conclusions that everyone can reconstruct from things they already know.

If we listen to what “Mother Culture” tells us, we doubt there is any reason to worry. All “official” predictions for the future assume that current trends continue unabated – more people will move to the already hopelessly overcrowded cities, overall population will continue to grow (although people have started realizing that, even in their hopelessly optimistic scenarios, population levels will level off somewhen towards the middle of the century, as population growth slowly starts declining already), the global cumulative production of plastics will grow from 9.2 billion tons in 2017 to 34 billion tons by 2050, and the aviation industry is expected to grow fivefold (!) by 2050 – all the while reaching “Net Zero” carbon emissions.

Tell me anyone actually believes this.

As Arnold Schroder says: “‘Net Zero by 2050’ is climate denial.”

But what people often overlook is that exponential growth is simply the beginning of a bell curve. Nature always restores the balance. All the growth we’ve experienced over the last few decades was never meant to stay. That’s not how the world works. What goes up must come down, and come down it will. All the suffering and starvation we thought we had solved has been merely prolonged, pushed further into the future, to be solved by some magical novel technology that never materialized.

Nothing can keep on growing forever, not even the universe itself.

We can’t even take care of our immediate environment, for Earth’s sake! Asking us to stop consuming and polluting is already too much, because it would mean inconveniences and discomforts that we’d rather avoid, even if that means destroying the world.

How dare we even talk about “saving the world”?

What, or better whom, can we even save? People? While this is usually the first thing that comes to mind (hello, anthropocentrism), the applicability is exceedingly difficult in the real world. By far most of the people are either perfectly fine with the way things are, wilfully ignore the severity of the crises converging in front of our eyes, or are at least indifferent – otherwise surely something must have changed by now. People don’t even want to be saved – so why bother? Call me a misanthrope (you wouldn’t be the first), but what should I care about people living highly pollutive and destructive lifestyles who are absolutely convinced that it is their birthright to use as many resources as they damn well please, and if entire ecosystems are wiped off the surface of the planet, then so be it, because “survival of the strongest” or some such.

With everything that happens around us, it's difficult not to feel desperate, to feel the touch of the uneasiness that lurks in the shadows, and instead of pushing it away and picking up your phone to distract yourself, I say embrace it.

The feeling that prompted me to write this rant has been a steady companion of mine for a long time, sometimes blazing high like a bushfire, sometimes smoldering quietly like an abandoned landfill, but never going away. I can feel its heat at the base of my skull at all times. It has not been caused by any single incident, but by the steadily increasing dread of day after day going by while this insanity continues and people act like it is perfectly normal.

I write essays and articles, in the vague hope that I touch at least some hearts, and that my readers are, if not bestowed with new knowledge or a new perspective, at least somewhat inspired. I also write because I want to organize my thoughts, to get stuff off my chest, and because I have the feeling that some thoughts should just be “out there,” although I’m well aware that this does not necessarily mean “out there in the real world,” but rather “out there, somewhere in the endless corridors full of whirring boxes in some server farm.” I try to write as if I would write for a younger me, things that I think would have helped me a lot if I would have known them sooner.

I don't write to “save the world.”

I document its decay.

But after a few years of shouting my two cents from the virtual rooftops of the online ghost town of anarcho-primitivists, rewilders, nihilistic environmentalists, tropical permaculturalists and luddites, I’m confident I have reached everyone in this rather small echo chamber. After all, you don't write to change people's minds – very few people can accomplish that – you write to verify what they already believe. I have no illusion about the impact that I can make with writing essays and articles from the hammock slung under my house in the sweltering heat of what used to be a tropical paradise – before the dominant culture bulldozed it and erected strip malls and gas stations and fourteen-lane highways.

But the thing is: this is not the end of the world. The collapse of civilization is not the end of the world. Civilizations have collapsed before, and humans survived. Hell, we survived for over three million years without civilization. But the question remains: what will we do to get through all that chaos and misery that will unfold over the next two or three decades? What will we have to do?

While all those terrible things happen all around us, Karn and I have decided that we will just try to stay out of the way and continue learning what we will need to know. This includes basic survival skills like foraging for local foods and herbs, tracking, trapping and hunting, basic first aid and herbalism, traditional crafts from woodworking to winemaking, both nonviolent means of conflict resolution and basic firearm training, but also things like midwifery (which will be widely appreciated after hospitals will become defunct). In the coming years we will need to become “Jacks of all trades” if we want to maximize both our own chances and those of our community.

While others continue to perpetuate the already disintegrating system, we will have to try to build communities and support networks outside of it, that work in parallel to it and at some point or another become more attractive for people than whatever diet version of the American Dream industrial civilization is still able to muster. I go as far as to boldly assume that there would be plenty of people today who would leave the cities in an instant if someone were to offer them debt relief (or refuge from debt collectors), free housing, meaningful work, a warm meal or two per day, a supportive community, and basic free healthcare.5

I know, I know. At the end of a nihilistic rant like this, something hopeful?

While this might be unexpected, I never said that humanity won’t make it. Some people surely will, although I’m well aware I might not be among them. I will try, though.

Another reason I still write is because it's one of my last attempts to raise awareness, to persuade others to save as much of the real world (as in “the living, breathing non-human world”) as possible, and to contribute to the conversation around how to do so, that I still care to pursue. I can’t reach the people in my village – at least not yet – but I was able to reach you.

I write to tell you that, despite the trials and tribulations I have detailed in the above, it’s not going to be all bad, and that living simply and within the limits of ones natural environment can be at least as rewarding (if not even a lot more so) than the absolute shitshow late-stage capitalism has to offer. I write to show that another way of life is not only possible, but desirable, despite its many downsides and difficulties. That life is still worth living, even if you don’t have a car, or electricity, or warm water, or a regular income. That there is a life outside of civilization, and it will soon be more attractive than slaving away your days for someone else’s enrichment while all you get is scraps.

I write not because I necessarily hold any illusions about the impact of my writing, but because one day, someone much younger than me will ask me why our generation didn't do more to save the world. I want to be able to say that, at the very least, I tried.

I really did.

Both in my immediate environment as well as in the larger society.

From my perspective, I did what I could. Maybe I would have reached more people with making videos on YouTube or TikTok, or travelling around participating in meetings and conferences, giving talks and speeches at events, but that’s simply not an option for me without vastly compromising my own well-being and my ability to care for the land I inhabit – and what counts is ultimately not the number of views and clicks, but the number of hearts you touch, which – by default – will be a tiny fraction of the former.

I might not have reached as many folks as I could have, I might not have been able to reforest the most severely degraded part of the Nature Reserve next to our garden, but I damn sure tried.

Without wanting to sound too full of myself, I do think that the knowledge of how to “save the world” can be found in my writing, if not always explicitly so then at least between the lines and in the references. This is not because I think I'm super smart and everybody should do what I say, but because “saving the world” is actually fairly easy. As I’ve stated in the beginning of this essay, the trick is to just leave her alone. Work less, buy less, do less. Reduce your dependence on the system that destroys her. Sit around more, not doing anything in particular. It's in those moments, sometimes while dozing off in the midday heat, that I have the gentlest thoughts and the best ideas. If you want to be at least somewhat healthy, it’s absolutely necessary to have some time every day that you just spend doing nothing. You are doing the world a favor by doing so. Not just because in that moment you don't consume, but because you have time to think. Thinking is dangerous for those who destroy the world, which is why they try to distract you every waking second of your life. “Pick up your phone,” screams the LED on top of the screen of your smartphone. “Turn off your brain, flood it with dopamine! True happiness is only one scroll away!”

It's difficult to compete for peoples’ attention if your adversary is TikTok’s dystopically named “For You” algorithm. It’s difficult to get people to have thoughts that feel uncomfortable, if comfort is all they were ever taught to desire. It’s difficult to even reach people, since their attention span has been destroyed – willfully – by the same techie overlords that enthusiastically promised us a world that works like a village.

Concluding, I have to state – for the record – that I might be wrong. As I’ve said above, this is a prediction, not a prophecy. If Business as Usual continues, as it has for the past decades, the bleak picture I’ve painted here is what we’re headed for.

A decline is inevitable, but it is up to us to adjust its steepness.

A revolution that topples the elites might sweep the planet after the first breadbasket failures, and maybe India will rise to lead the global permaculture revolution. Maybe some imminent massive disruption will be enough to galvanize a critical mass, and maybe that “collapse-awareness tipping point” I mentioned earlier will be reached in time to soften the impact. I truly hope so, on some days more and on some days less. I wrote this essay exclusively on the days where I felt less like hoping, but now that I finished it, I feel a bit better, although I can’t quite pin down why. Maybe because some things just need to be said out loud. Maybe because, as I’ve managed to achieve before, I might succeed in putting into words what others have felt for a long time already.

Whatever happens, I won't stop writing. I find it therapeutic, and I really enjoy the feedback I sometimes get.

But I’m done saving a world that doesn’t want to be saved.

I write stuff like the above in my free time, when I’m not tending the piece of land we’re rewilding here at Feun Foo. As a subsistence farmer by profession I don’t have a regular income, so if you have a few bucks to spare please consider supporting my work with a small donation:

If you want to support our project on a regular basis, you can become a Patron for as little as $1 per month - cheaper than a paid subscription!

The IPCC’s official stance is that, if we want to avoid the (somewhat arbitrary) threshold of 1.5°C (after which six tipping points are predicted to be triggered), we will have to halve emissions until 2030. But next year - 2024! - is the year in which the world will likely cross that threshold for the first time. Do we really expect the climate to cool down a lot after that?

And what does the above mean for how we should view and assess the predictions and guidelines of the IPCC?

Although there is some serious bickering over some of the details going on - most of which presumes nonexistent future technologies and obviously unrealistic science-fiction scenarios like space mining, which is such a blatant delusion that I won’t even waste my time writing about it. Sometimes the techies’ own words are the best criticism of their ideas. However, the bigger picture he paints and the general trend he outlines remain undisputed.

Please also note that the trouble starts long before oil “runs out.”

I initially thought about not naming them, but it’s the end of the world, so whatever: it’s the Native Species Restoration Foundation, whose director’s daughter mans their phone (in blatant nepotistic fashion) and thinks she’s a lot smarter than anyone calling her asking for advice. Some people really enjoy their place in the hierarchy.

Sure, the healthcare the system currently provides might encompass more treatments, but what good is an emergency operation if you and your entire family are deeply indebted for the rest of your lives? How much longer will the masses even be able to even afford basic healthcare, as resources dwindle and supply chains brittle?

I appreciate your efforts in the world, both the physical efforts and those that reside outside our senses.

I am your neighbor, so to speak, living in northwestern Cambodia since 2006. My wife, son and I have a 1-hectare farm. High expectations for this tiny piece of earth: the place where my son learns how to take care of himself in a changing world (the villagers where we live know more about the living world and how to survive in it than I will ever learn), as a source of water, food and fiber and home, and a place my wife can produce the things she needs to survive should I no longer be here or unable to work as I do now. Of course, we have successes and failures nearly every day. As you are probably well aware, when tiny humans attempt to create a functioning ecosystem that produces things civilized humans need on a small piece of damaged earth, you are trying to achieve the impossible.

Like you, I try to explain to people what is happening here in Cambodia and in the Asia Pacific. That people here, almost to a one, want to live modern, affluent lives and are willing to work very hard to achieve this, and are also willing to destroy the living world to get what they think they deserve, as many countries have already done and continue to do.

I originally came to Cambodia to work for a nonprofit doing climate change adaptation/mitigation projects. Strangely, while in Cambodia doing this ‘save the world work,’ I realized not only could I not ‘save the world,’ but that the living world was almost assuredly screwed.

Working, learning and traveling around South, Southeast and East Asia (where 55% of the world’s human population lives) for the past 20 years, it became clear that the people living in these regions, as societies, believed in and lived the myth of human supremacy just as profoundly as those living in more ‘affluent’ regions of the civilized world. For example, the material culture in rural Cambodia when I first came here—as much as a white man from the USA can understand this— was based on subsistence agriculture and rooted in a spiritual ecology of Animistic Buddhism. The simple material living and the deep understanding of their land lured me into believing I’d found my place and people in the world. But as the forests around me were felled for green revolution agriculture and the karst hillsides disappeared to build highways and dams, the people mostly cheered. While the rural communities and households who took part in our rooftop rainwater harvesting, home-scale water filtration, organic agriculture, and community bank projects were happy to be a part of them and worked hard to make them successful, nearly all these people wanted for themselves and assuredly for their children, by their own and open admission, to live modern, affluent lives. They wanted to drive cars to work in air-conditioned offices, shop in supermarkets, have large homes equipped with all the modern conveniences, go to shopping malls, etc. In short, they wanted to thrive in an ecocidal economy.

As a person who grew up with all the benefits of ecocidal living—the effects of the steady collapse of the biosphere were not as obvious when I was growing up as they are now— it is hard to talk about modern, affluent living being ecocidal, without coming off as an asshole, perhaps rightly so. Still, when I think of the destruction of habitats and ecosystems in the name of building a global omnicidal culture, it is heartbreaking.

Sorry for such a long rant. I wanted to let you know that someone appreciated your writing and efforts at creating a more life-centric world.

I wish you and your loved ones long lives filled with love!

The Main problem is: There are too many people living on earth. So, not all of them could live like you, even if they wanted to.