It’s time for Anarcho-Primitivism to reconsider its stance on Domestication | Reader’s Correspondence

New findings overturn old misconceptions --- [Estimated reading time: 30 min.]

I’ve recently received a great comment on one of the earliest essays on this blog (Bite the Hand that Claims to Feed You - Don’t Defend Civilization!) that merits closer inspection. A reader named Ephemeral Presence inquired about my permissive use of the phrase “[to keep] a few tame animals […] close by” when talking about non-civilized modes of subsistence, suggesting that “taming animals” means that we meddle with the natural behavior of the animal, which might lead to domestication.

I haven’t done a Reader’s Correspondence in a while (but it’s something the smartass part of my personality enjoys a great deal), so please allow me to use this opportunity to share my thoughts on the issue. Since this topic has been on my mind for quite some time now (ever since I discovered Arnold Schroder’s podcast Fight Like An Animal), I’ve long played with the thought about writing a few words regarding my personal stance. Let this be the occasion.

Many thanks to Ephemeral Presence for inspiring this brief Rambling.

It has become somewhat of a fun side quest for me to make Anarcho-Primitivism more broadly attractive, inviting & inclusive (I sometimes say “more family-friendly”), and to help update terminology and include new scientific findings of the past two decades – to “modernize primitivism,” if you want. This endeavor quite naturally involves stirring up pots, stepping on toes, and overturning dusty, old conceptions. The following shall be no different, but I hope that, as with my essay series on delayed-return hunter-gatherers, I can help kickstart a few fruitful discussions here and there.

Be advised, though: this might be my most controversial take thus far.

As you can already imagine, regarding the topic of Domestication I have a very different view than “traditional” anarcho-primitivism. The classic divide has been presented as a prevalent binary choice1 between Wildness and Domestication – where everything that’s “wild” is “good,” and everything that’s “domesticated” is “bad.” We have domesticated other beings (and ourselves!), which is bad, and now that we’ve seen the “evils” that “domestication” produces, we should strive for “wildness” again instead – John Zerzan’s line of reasoning.2

And while there is undoubtedly a lot of truth contained in this dichotomy (at least from a certain perspective within a certain frame), we should be open to have our ideas challenged and adapt our beliefs when new perspectives emerge from recent scientific findings – as is the case with domestication.

As so often, reality is a whole lot more nuanced than our abstract mental representations of it.

Arnold Schroder (who is not a primitivist3) recounted in several episodes of his podcast4 how challenging for him as an ex-Earth-First!er and lifelong radical environmental activist this realization initially was. For over twenty years of his life, he was convinced that he was “absolutely and categorically ‘against domestication’ of any kind,” defending instead the concept of “Wildness” – but a closer examination of the biological processes that underlie domestication ultimately made him change his mind. In his words, “our conception of what domestication is is far too broad and categorical.” But more on that in a bit.

Personally, I had slightly less of a commitment to this exact terminology, perhaps simply because I’ve spent fewer years taking sides. Although I occasionally use the term “(hyper-/over-)domesticated” as an insult, it is more of a figure of speech, implicating that if you try to take certain aspects of the domestication process to their extreme, you end up living like ants or termites (which I find undesirable for us humans). I had my first personal experiences with food cultivation and animal husbandry around the same time I discovered anarcho-primitivism, so the “primitivist standard narrative” of “agriculture” as the “original sin” – while being broadly correct and a concise frame for a foundational mythology – was also always a bit of an oversimplification for me.

Plant Cultivation ≠ Agriculture; Animal Husbandry ≠ Dominance Hierarchy

As I hopefully made clear in previous works, in reality there are many ways to cultivate plants, and most of them are rather inconspicuous. Only the method that Daniel Quinn has called “totalitarian agriculture” – grain monocultures (especially when irrigated), to be more precise – is prone to give rise to the state, civilization and all concomitant ills. Other staple crops don’t lend themselves to being appropriated as easily as grains – and hence don’t allow for elites to parasitize on the surplus. As James C. Scott has pointed out, there is a reason why there were no cassava states or breadfruit states. Only grain can be assessed, divided, measured, stored and transported with the ease that allows for more “complex” societies (with rigid dominance hierarchies, non-productive elites and standing armies) to emerge.

Instead of blaming the cultivation of plants (i.e. “agriculture”) in general, the real culprit is this intensified & highly specific form of plant cultivation.

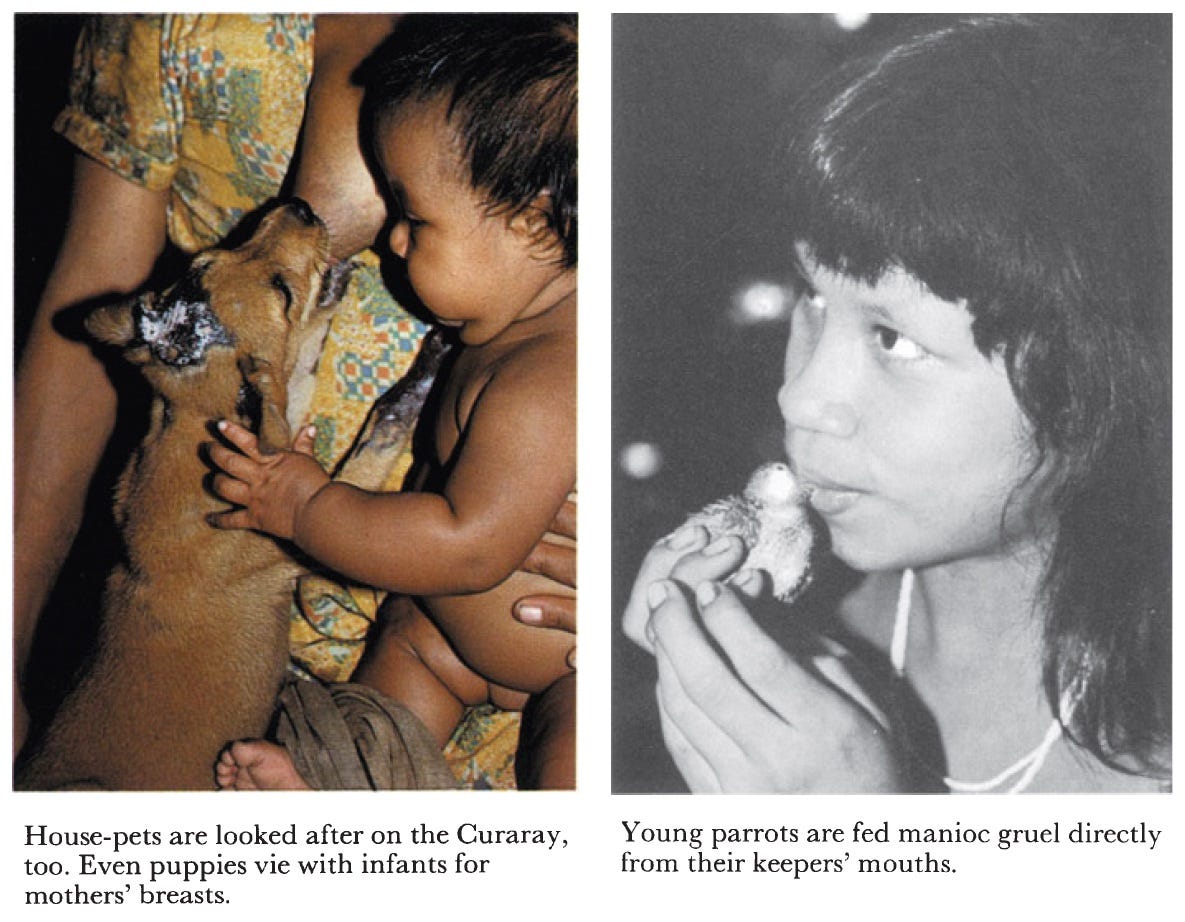

Similar confusion abounds around animal husbandry. Most contemporary indigenous societies keep pets of some sorts, like Amazonian tribes who adopt young animals (from parrots to monkeys) whose mother has been killed by hunters. Many other cultures keep herd animals (the Sami or the Massai) or a few other domesticates around. Dogs are a regular sight among hunter-gatherers in all climate zones, and chicken are quite common as well.

It certainly seems that indigenous societies themselves don’t think there is something categorically wrong with “keeping tame animals around.”

Given, there is a big difference between indigenous hunter-gatherers and indigenous pastoralists. I don’t have anything against pastoralism per se (although it’s definitely not my favorite subsistence mode) – it’s an adaptation to certain more marginal ecosystems in rare stable climatic periods that allow for denser populations and some level of dominance hierarchies. An interesting debate can be had about whether pastoralism could be compatible with anarcho-primitivist ideals (I tend to think not, because it allows for warrior cults – and hence patriarchy! – to emerge), but this is not the place for this discussion.

Although the initial comment by Ephemeral Presence suggested no such thing, in certain circles (e.g. green anarchists, primitivists, animal rights activists), it is often assumed that “keeping animals” is always & inherently based on a dominance hierarchy, in which, say, the rancher dominates his cattle. And while that is certainly one way to look at the issue, in reality many farmers (especially smallholders, but also some with larger operations) deeply love and care for their animals.5 Loving/respecting and eating animals is only perceived as a contradiction in contemporary society, which is by many measures the most alienated culture ever created by human beings. Most people in overdeveloped societies have never actually spent time with farmers or farm animals, and never had to raise and/or kill an animal for food themselves. Meat appears out of thin air on supermarket shelves as an inert food resource, a uniform industrial product that bears no resemblance whatsoever to the animal from whence it came.

After a series of graphic documentaries and other footage depicting the utterly abhorrent conditions in industrial animal feeding operations drew attention to the issue of how the dominant culture “produces” meat, many people (left-brainedly) decided that the only reasonable response would be the other extreme: to “go vegan” and be “against animal farming” because it is inherently “cruel” – terms like “imprisonment” and “enslavement” abound.

After all, those poor creatures are deprived of their freedom, right?

I am aware that many people won’t like hearing this, but domesticated animals (outside of factory farms, of course!) often have it easier and thus better than their wild cousins. When it rains, they have a roof over their head, and their human friends always make sure they are supplied with the most delicious foods. They have ample opportunities to forage, play & mate, have plenty of offspring, and they have capable caretakers looking after them when they are sick, injured or otherwise in need of help.

In our Food Jungle, our animal friends are fed leftover bananas, avocadoes, durian, jackfruit, santol – plus a cup of organic rice per day for the chickens and a diverse, hand-selected bundle of herbs, grasses and tree foliage for the rabbits. During the day, they forage for their favorite foods and socialize as they please.

The fence around the chicken pen is rather useless in its intended function and thus represents a mere symbolic boundary anyway – our semi-wild chickens can fly pretty well, so I’m sure they don’t perceive of themselves as being “limited in their freedom” by us in any way.

And our rabbits spend their days in a fenced-in enclosure that’s large enough for them to run around as much as they like. In dry season, we move the enclosure once a week so there’s fresh grass, and we always make sure their place has abundant shadow, places to hide, and at least a dozen species of edible wild plants for them. I’m not sure if our rabbits would call their home a “prison” if you’d ask them. Yes, there’s a fence, but that’s mostly for their own protection (and for our convenience.)

Sure, we occasionally kill one of them, but how exactly do people imagine wild prey animals’ lives usually end? Do they get to live until ripe, old age and spend their final days on a deathbed, surrounded by family? No – becoming food for predators before they “get old” is part of their evolutionary reality. This is not a “tragedy” that should be avoided (although it might seem like one from an anthropocentric view), nor does it mean that they are being “dominated” – it’s just how life is for their species. I for myself would prefer a quick & painless cervical dislocation over a prolonged period of terminal illness.

Instead of judging the slaughter of farm animals by our current cultural standards, it makes more sense to view us humans as simply fulfilling the role of a natural predator – although with some important extras.

But I’m digressing: after all, the topic at hand is domestication, not vegetarianism.

So what exactly is domestication, and how terrible is it?

Common primitivist sense has it that domestication turns free beings into slaves: it makes them dumb,6 docile, and easy to manage. They become dependent on their “domesticator’ – i.e. his subjects – and can thus be exploited at will.

Domestication, from this point of view, is the enslavement of animals, and thus synonymous with domination.

As a matter of fact, actual primitivist definitions of the term are often incoherent and vague. For instance, The Anarcho-Primitivist FAQ by Stiller defines “Domestication” as “the will to dominate animals and plants” [Emphasis added]. Etymologically speaking both words, “dom-esticate” and “dom-inate,” derive from the same PIE root word (*dem-, which simply means “house” or “to build” and in no way implies any inherent dominance hierarchy), so the relationship between the terms might as well be more correlation than causation.

“Domestication” might simply mean “belonging to the house.”7

Summarizing fundamental concepts in A Primitivist Primer, John Moore (quoting John Zerzan) describes domestication as being opposed to freedom – a term that is itself in desperate need of definition whenever it pops up. But, regardless of what definition we follow, don’t all relationships involve compromises on our individual freedom, whether it’s between humans or across species? Don’t they all necessitate restraint of some sort or another, usually on immediate self-interest?

Yes, we give up certain “freedoms” when we enter a relationship, but those lost freedoms are usually far outweighed the long-term benefits for both parties involved.

A bit of freedom can be a worthwhile sacrifice.

In his 2022 paper “What is domestication?” biologist Michael D. Purugganan describes the “instinctual consensus” among the general public, according to which domestication means something along the lines of “the plants and animals found under the care of humans that provide us with benefits and which have evolved under our control.”

Yet, as recent research has shown in stunning detail, termites, leafcutter ants8 and ambrosia beetles have domesticated certain species of fungi, so defining “domestication” in purely anthropocentric terms no longer makes any sense.

Instead, Purugganan offers a broader definition of Domestication:

“A coevolutionary process that arises from a mutualism, in which one species (the domesticator) constructs an environment where it actively manages both the survival and reproduction of another species (the domesticate) in order to provide the former with resources and/or services.”

Hence, one of the activities of the domesticator is simply niche construction, which – again – can be done in a mind- and respectful way, catering to the specific needs of an animal, plant or fungus.

But, without getting deeper into all the complexities of trying to define the term more generally, at its very core, human domestication of other animals centers around the process of selecting against aggression. That’s what early farmers and pastoralists did to the animals that they kept and consumed regularly, and that’s what we here at Feun Foo Permaculture & Rewilding are still doing with our chickens and rabbits. There is a surprisingly large variability in expressed behaviors among all animals, and some individuals tend more towards aggressive behaviors than others. This serves important functions and has its appropriate applications in certain (extreme) circumstances,9 but I can say from experience that you really don’t want an overly aggressive rooster in your flock – they can prove detrimental to group harmony & health, and might even start attacking you.10

Most of the domesticated animals we cull have behavioral traits that are undesirable, such as a hen that doesn’t protect her chicks, or a young rooster that develops the habit of eating eggs.11 In Nature, such behavior would simply be self-terminating – if not immediately, then definitely over longer periods of time.

So if you have an animal in your flock or herd that is always looking for trouble, that’s gonna be the individual you’ll eat next – it’s as simple as that. No need to pass those genes on to the next generation.

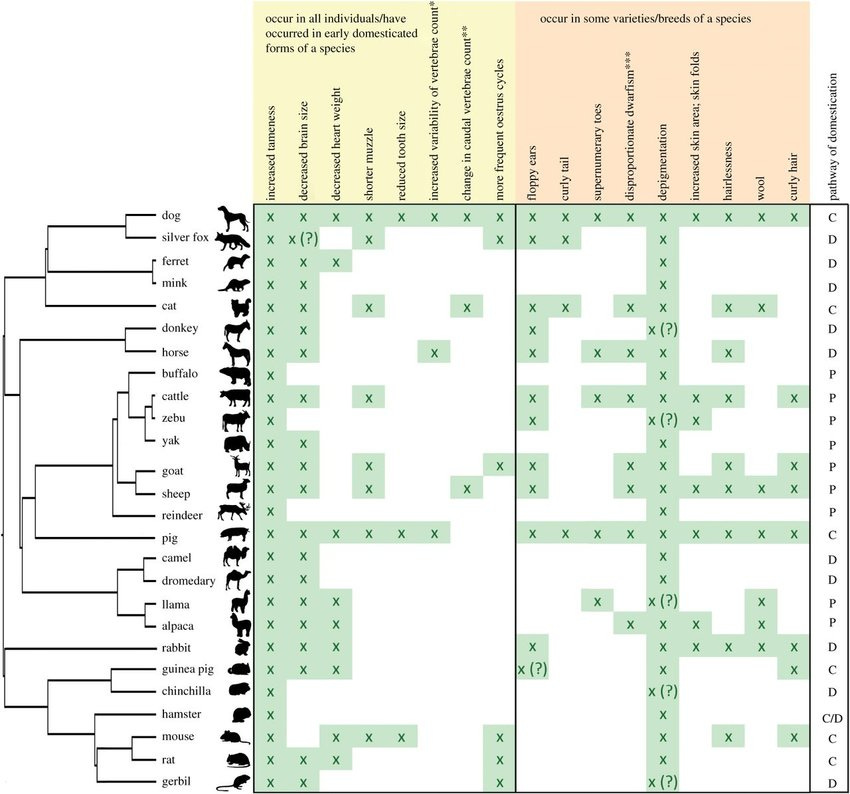

Over time, those selective pressures (“guided evolution”) against aggression lead to a certain set of changes in the animal in question.

In a famous example, Russian scientists were able to domesticate foxes in less than ten generations, simply by selecting the foxes that were the friendliest towards humans (i.e. against aggression). Within this evolutionary nanosecond, they soon found themselves presented with foxes with floppy ears and short snouts that were wagging their tails, yapping and climbing the legs of their human supervisors.12 The mere selection for one trait triggers a concomitant host of other physical and mental changes as well, with considerable overlap between different species.

Sure, another accompanying feature of the domestication process (reduced reactive aggression) can be a shrinking of overall brain size (which has happened to us humans over the course of the past 10,000 years, as we created increasingly dense settlements with ever larger population sizes13), but also an enlargement of certain regions in the brain (as observed among chickens, foxes, domestic pigeons & rabbits).14

Additionally, there are other (highly interesting) aspects that accompany domestication, such as more juvenile facial features, reduced teeth and snouts, altered hairiness and pigmentation,15 earlier sexual maturation, more frequent mating, a decrease in sexual dimorphism (indicating a greater power balance between the sexes), and – most importantly – developmental changes and a prolonging of the juvenile (i.e. “neotenous”) phase of increased behavioral plasticity.16

Domesticated animals are, as a result, much more tolerant of each other, can live in larger & denser groups, and often have more complex internal social organizations as a result. Those relatively novel social organizations come with their own set of long-term risks (overgrazing/overpopulation/overshoot), but ideally it’s not like the domesticated version of an animal replaces their wild predecessors – it merely adds one more option, one more evolutionary pathway, thus contributing to Diversity.17 If it doesn’t work in the long term, so what? Evolution’s approach to behavioral variation is pretty much to throw a bunch of things at a wall and see what sticks.

If some domesticated animals were able to sustain their human keepers over thousands of years without leading to the ruthless exploitation of the animal in question or a degradation of their environment at large, I’d say the experiment was definitely at least worth a try.

It follows that the process of domestication is a lot more complex and nuanced than one species dominating & exerting control over another.

What’s not domestication

What many people in the broader radical environmentalist/ green anarchist/ primitivist/ rewilding/ animal rights circle think of when they hear “domestication” is some guy beating an ox all day long to force it to toil for him, pulling a plow or carrying heavy loads. The term for creatures abused in such manner is draft animals, although this practice might be more appropriately termed “animal slavery.”18 This has nothing to do with domestication per se, it is forcing already domesticated animals to perform labor for you.

How you treat your animal companions has absolutely nothing to do with domestication itself, but with your own attitude, morals and culture.

Another common misconception is that the domestication of dogs was basically the process of turning wolves into pugs and chihuahuas. While one certainly allowed the other, the deformed dog breeds that so commonly accompany modern humans (who are often removed from evolutionary reality to a similar extent, if not physically than at least mentally), are a result of selective animal breeding towards certain features (such as shorter snouts). Domestication happened much earlier (according to the latest literature review around ~23,000 years ago, perhaps earlier), and led to strong, creative, highly intelligent animals that could solve problems, perform complex tasks, and communicate with humans (such as hunting dogs, shepherd dogs, and guide dogs for blind people). The relationship between dogs and humans has often been a mutually beneficial one, given that the culture in question elicits adequate levels of respect towards other life forms.

Concluding, it seems like a lot of the predominant criticisms of “domestication” are actually criticisms of a) selective breeding, and b) farming practices – more precisely, of modern, industrial farming practices. Such practices are often pronouncedly different in more traditional settings. My grandfather kept sheep (and bees, another “domesticated” animal), and the love and care he had for his animal friends was heartwarming. When an ewe was about to lamb, he would sleep alongside her in the hay to be able to help her deliver. There was an ewe by the name of Pünktchen that developed a special relationship to him, and practically became his best friend.

And this is not a quaint exception: traditional herding cultures worship the animals that sustain them. They acknowledge this relationship of mutual dependence, the sacred ties that bind them to their nonhuman companions.

Did we domesticate ourselves, and – if yes – when and why?

One pressing question left to answer is: what about us humans? Where do we stand in regard to domestication?

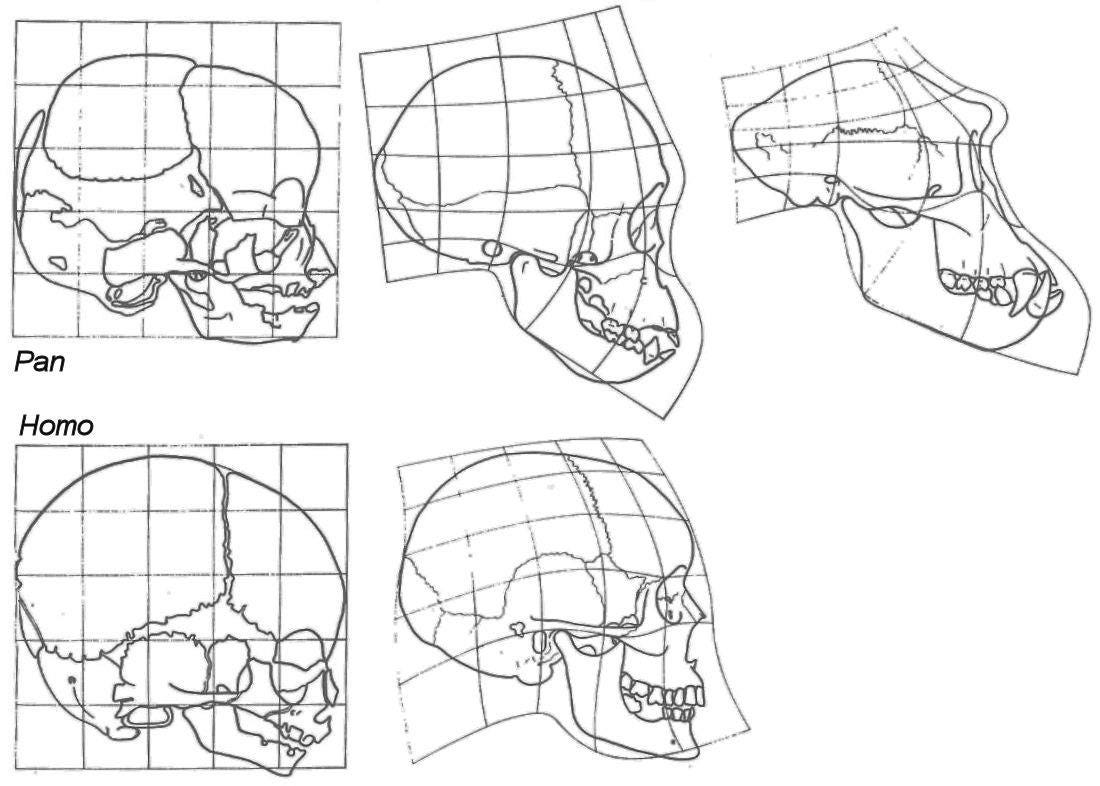

There is a theory called the “self-domestication hypothesis”19 which convincingly argues that those exact changes to behavior (or, to be more precise, the conscious shifting of the behavioral range away from the aggressive end of the spectrum) observed among domesticated animals is also what explains the shift from a more chimp-like, hierarchical ancestor to the egalitarian band societies of Homo sapiens. Somehow, our genus has created subtle cultural mechanisms (“leveling mechanisms”) that select against aggression, as violent individuals (usually males) were shunned, excluded, exiled, or simply killed (and were thus systematically excluded from the gene pool).

The result is a more “docile” population with increased neoteny – the retention of juvenile features (such as playfulness and behavioral flexibility) into adulthood – and less pronounced dominance hierarchies, leading more peaceful lives. And this is why, compared to all other social primates except bonobos, we are firmly on the egalitarian side of the spectrum (despite the recent few thousand years of highly stratified civilizations, which usually don’t last long and merely add breadth to the known behavioral range of our species).

In addition, we became much more tolerant of strangers, and were thus able to create larger, more complex social networks – and we gained the ability to cooperate and share knowledge & skills on larger scales as a result.20

Domestication is, in a way, the very thing that made us human.

If we would be “against domestication,” wouldn’t that also mean that we are against our own species – a product of domestication – and should strive to recreate some earlier, “wilder” (and thus more aggressive) version of ourselves?

And think about it: our skull shape and facial features resemble not those of adults, but of juvenile chimpanzees. Additionally, we have lost most body hair, men are on average only slightly taller than women, and we surely do mate frequently. We have smaller teeth and “shorter snouts” than any of our ancestors, and we are most certainly the species with the most behavioral plasticity (i.e. the widest range of potential behaviors) in the world. Admittedly, our brains have grown for most of our species’ evolutionary history, but that is more connected to positive feedback between social complexity, language, hunting practices and dietary changes (cooking food) than to the processes of domestication.

A strong argument for this hypothesis is the process that separated bonobos from chimpanzees, who share a common ancestor about two million years ago. It is likely that a population of those proto-bonobos found itself geographically separated from other populations (perhaps by the formation of the Congo river around the same time), and thus isolated. In their new habitat, they had much less intraspecies competition, and as a result enjoyed greater abundance of food and a less threatening environment. Moreover, they now didn’t have to compete against gorillas as well, further decreasing pressure & competition and reducing the need for violent or aggressive behavior.

Somewhen along the evolutionary trajectory of bonobos, coalitions of females were able to subdue aggressive males. Astonishingly, they were successful for long enough to influence the behavior of the group permanently, until their sustained behavioral changes led to changes to their genome that ultimately separated them from chimpanzees.21 They domesticated themselves. Does that mean bonobos are “less wild” than chimpanzees? Or should we maybe reconsider what we mean by “Wildness”?

Self-domestication might not even be limited to primates: a recent study proposes that elephants might have domesticated themselves as well.22

There is another famous example for what can happen as a result of selection against aggression, one that holds a very valuable political message as well. The strongest males of a troop of baboons foraged in a garbage dump, and as a result all died from eating contaminated meat. The survivors were the less aggressive males23 and the females, who consequently reorganized their troop’s society around a more egalitarian baseline.

What’s remarkable is that even as new males from other troops joined the group over time, the overall culture of the troop remained egalitarian, although we can expect that more aggressive males were among the newcomers. Given enough time (and the miracle of sufficient geographic isolation), maybe this troop would have evolved into a more egalitarian bonobo-baboon, or bonoboon.

As in the above examples, our own ancestors persistently chose egalitarianism over authoritarianism, until it manifested in the behavior and morphology – and thus the genome of our species. It seems entirely plausible that the whole journey from Australopithecus (and earlier!) to Homo sapiens is one of increasing self-domestication. The answer to the question of when this domestication happened is: all the time. Continuously. It’s a trend that dates back millions of years, but that seems to have accelerated with the most recent species of humans, especially H. sapiens.24

And why did we select against aggression? Because life is decidedly easier for all members of a group when aggression & violence are kept in check as much as possible and egalitarianism predominates. Authoritarian social structures benefit a small elite at the expense of everyone else, who is often rather miserable in such arrangements.

For us humans, highly social and behaviorally plastic mammals that we are, survival is certainly possible in both egalitarian and authoritarian social organizations, but much more comfortable and less stressful for everyone involved when the focus is on cooperation and equal access to power and decision-making.

Meddling with other species’ behavior – a good or a bad thing?

The last point that needs to be briefly addressed is an ethical evaluation of the “meddling” with other species’ behavior. Classic primitivist dogma holds that this is reprehensible, almost amounting to a perceived “contamination” of the animal’s “purity” through human interaction.

To be honest, I personally don’t think that influencing (or “meddling with”) other species’ behavior is necessarily a bad thing. Quite the contrary, it can be a profoundly positive thing. Interspecies symbiotic relationships are ubiquitous throughout all ecosystems, and they involve – by necessity – two organisms “meddling” with each other’s “natural behavior.”

We assist our fruit trees with certain tasks, and in return they shower us with seasonal abundance. The chickens gift us surplus eggs, and occasionally we kill & eat one of them, but we provide them with a safer, more stable and more abundant environment. Our partners surely get something out of the deal as well.

In addition, behavior is not static, but ever-changing and perpetually in flux, a dynamic tension which ensures resilience & adaptability in the face of stressors & environmental changes. Therefore, I don’t think that there is just one set of inherent behaviors in each species and those should be kept separated from other existing possibilities as good as possible. If a certain, inconspicuous terrestrial mammal (Pakicetus) hadn’t slowly changed their behavior a few million years ago and spent more and more time in- and under water, whales and dolphins wouldn’t exist. Likewise, if plants wouldn’t have started accommodating & serving insects (and thus changing those insects’ behavior), we wouldn’t have flowers. Did flowers “domesticate” the bees, or did the bees “domesticate” the flowers?

Regrettably, most scientific debates (stuck in the left brain hemisphere’s mode of thinking as they are) revolve around a binary question phrased like this, often completely ignoring that this is not an “either-or” distinction to begin with. Both sides can be “true,” or at the very least contain truth. So, in a sense, the flowers and pollinators “domesticated” each other, as did the leafcutter ants and the fungus they both feed and feed on.

And the same is true for our modern domesticates: did we domesticate the sheep, or did the sheep domesticate us? Was it us who domesticated wheat or was it the other way round?

Those novel organisms surely made us work for them, perhaps harder than we ever had to. They often require near-constant attention & care (energy, time and resources that you wouldn’t have to expend with wild animals and plants). And yet we usually don’t consider ourselves their slaves or servants, despite catering to their every need and occasionally tolerating considerable difficulty and discomfort for their sake.

But let’s also remember that hard work doesn’t always have to be toil, especially when you consider how much your animals give back to you. The effort it takes to supply our rabbits with additional feed is well worth it for us – just seeing how happy and excited that makes them is reward enough, plus they constantly convert vegetation into fertilizer.

We changed them, yes, but they changed us as well: our mutualistic relationship has altered our own cultures, and hence our behavior – which will in turn influence our evolution in the long term (see: Pakicetus).

Behavior is one of the main drivers of Evolution,25 and increasing self-awareness and interconnection seem to be some of its aims. If we strive for a more interconnected world in the long term, it makes sense to explore more different ways to forge those connections ourselves.

And maybe that’s our destiny. Maybe that’s how we can put our species’ unique capabilities to use for the greater good, to serve Life.

My favorite example of the kind of connection I’m talking about is the famous relationship between honeyguide birds and the Hadza foragers (and other traditional groups like the Yao) of Tanzania. The regular reader of this blog is surely familiar with this story, but allow me to briefly summarize:

Beehives in Tanzania’s shrublands are usually high up in the trees, so humans have a hard time finding them. But not so the honeyguide bird, which can locate them from the air with ease. When humans want to go honey-hunting, they call out for potential honeyguides in the area. If a honeyguide is around and happens to be hungry, the honeyguide bird answers the call, and consequently leads the group of humans to a tree with a beehive. Once there, the humans start a fire, smoke out the bees, harvest the hive, eat the honey & larvae, and toss the leftover wax to the honeyguide bird, who feeds on it.

Should the Hadza stop “meddling” with the honeyguide birds’ behavior, in order not to accidentally “domesticate” them? Or is it time for us to re-evaluate what those concepts actually mean, both for us and for the other living beings we share this planet with?

Another (less famous) example of interspecies cooperation is that of “human-dolphin cooperative fishery” – documented both in Brazil and Myanmar! – in which the dolphins help the fishermen by driving fish into their cast nets, because both parties are able to catch more fish this way.

Wouldn’t it be amazing to live in a world where such connections would be the norm, and not the exception?

During the (mutual) domestication of another species, we humans do indeed exert a certain evolutionary pressure towards the “target species,” but so do other predators who often push selection towards health, strength, intelligence & vigor by eliminating weaker individuals of the prey species from the gene pool. Another aspect that non-human predators push selection for is group coherence. Wherever coordinated communal hunts are aimed at separating very young or old individuals from the herd, the prey species can ward off attackers by keeping their lines closed, sticking together and attacking individual predators together. As shown in countless wildlife documentaries, sometimes adult herbivores gang up and drive off carnivores eyeing one of their children.

It’s a sacred dance, as old as time itself, between predator and prey. Both constantly influence each other’s behavior, and thus evolve together over time.

Meddling with each other’s behavior is what helps them adapt and survive, it’s what makes the Wheel of Life spin and allows Evolution to unfold and create wonders beyond imagination.

It seems obvious to me that there is no one set of “wild” behaviors that have to be kept pure at all costs. I also don’t agree that different species have to stay separated. Quite the contrary, I think those of us who feel like doing so should strive for more conscious interaction between all kinds of living beings.

Just think of the possibilities that exist from that perspective!

Sure, symbiotic relationships carry an inherent risk: mutual dependence. If the fig tree goes extinct, then so does the wasp who lays her eggs in the figs, and if the wasp goes extinct, so does the fig tree because nobody pollinates her inverted flowers. But those relationships, in their totality, also make the ecosystem itself stronger and more resilient.

And what’s so reprehensible about mutually beneficial coevolution?

There are definitely plenty of debates to be had, about the extent to which we should directly influence other species’ evolved behavior, possible guidelines and definite taboos, but, going forward, the most important thing to remember is Daniel Quinn’s adage:

There is no one right way for all the people in the world to live.

The global ecosystem functions so well precisely because of the unfathomable diversity of approaches Life came up with, and the more different things we throw at the proverbial wall, the more likely it is that some of them stick. Instead of categorically denying any “meddling” with nonhuman animals, let us ask how we can do so respectfully and with foresight, reverence & wisdom.

Dr. Shane Simonsen’s idea of humans as the “Universal Symbiont” definitely resonates with me, although we may differ on the exact lengths we should go to in order to achieve this (and the precise amount of control/influence we should exercise over other beings). But since the most dangerous and ethically questionable high-tech approaches to this topic (for instance CRISPR/Cas9) will soon enough become physically impossible due to resource constraints and other stressors to the underlying infrastructure of the techno-industrialist system, it seems likely that most worst-case scenarios regarding genetic engineering will never materialize.

And apart from things like gene editing26 to make species conform to our will, carefully nudging Evolution’s direction does not have to be a bad thing.

I, for myself, want our descendants to live in a diverse, colorful world full of wonders, where they cooperate and communicate with a whole panoply of other species, and where they have as many non-human friends as human friends. A world in which all of us work together on the sacred task of turning the wheel of life, and see where it might lead us.

We can learn so much just from spending time with other animals, both about them and about ourselves. We can contemplate both our differences and our similarities. They can help us understand that, deep down, we’re all the same. We feel the same emotions,27 and have the same basic goals in life. We require the same things to achieve them, and us awaits the same ultimate fate.

None of my personal experiences with “animal husbandry” have led me to become more alienated, violent, careless, or disrespectful towards them – quite the contrary: they have helped me reconnect to the Living World and develop the profound reverence for Life that has driven me ever since.

In fact, my own rewilding journey wouldn’t even have been possible without the many domesticated plants and animals that I care for and share my habitat with. I owe them everything; I feed them, and they feed me. Because of our proximity and intimacy, they can easily show us “unruly children of civilization” what we’ve been missing for so long.

If we are serious about our ambitions to rewild and live lives that are more in tune with the lifestyles we evolved for, we have to let go of overly simplistic abstractions & binaries, and plunge into the new realms of possibilities that open up when we embrace the creation and maintenance of relationships that make up the Community of Life.

We’d be unwise to forego such a dazzling array of opportunities.

Oh, and for those that don’t know it yet:

I write stuff like the above in my free time, when I’m not tending the piece of land we’re rewilding here at Feun Foo. As a subsistence farmer by profession I don’t have a regular income, so if you have a few bucks to spare please consider supporting my work with a small donation:

If you want to support our project on a regular basis, you can become a Patron for as little as $1 per month - cheaper than a paid subscription!

Hello, left brain, my old friend…

No disrespect to the man! His texts make a great base for the foundational mythology of a variety of diverse cultures of “future primitives.” We owe him so much.

One of the main issues Arnold has with anarcho-primitivism is that he encountered earlier, more dogmatic primitivists who claimed that you “leave the virtuous path” as soon as you plant a seed or keep some chickens. Nonetheless, his brilliant synthesis of biology and politics is essential to – and in many respects actually confirms and underpins – anarcho-primitivism.

Most recently in #74: Sub-Self, Meet Meta-Self (from 17:30 min. onwards).

This is obviously not true for CAFOs (concentrated animal feeding operations, aka “factory farms”), but nobody should ever defend those anyway.

Calling domesticated animals “dumb” is actually pretty arrogant, ignorant and anthropocentric, and only shows that the person in question has spent little time with cows, sheep, goats, pigs or chickens. Sure, if we define “intelligence” in a way that makes us humans feel special, they seem inferior – they didn’t invent cars or the internet – but we primitivists should be above such simplistic and self-serving notions. Really, you’d be surprised how clever those domesticates can be.

The etymological origin of the word “domesticate”: from Medieval Latin domesticatus, past participle of domesticare “to tame,” literally “to dwell in a house,” from Latin domesticus “belonging to the household,” from domus “house,” from PIE *dom-o- “house,” from root *dem- “house, household.” (Source)

For a truly stunning cinematographic masterpiece detailing the relationship between leaf cutter ants and their fungus, be sure to check out David Attenborough’s documentary series The Green Planet.

Such as when an outside threat necessitates a violent response, and the aggressive/destructive behavior can be directed towards an outgroup target while serving the greater good of the ingroup.

A rooster at our last project managed to kick my brother’s leg with his spur, causing a surprisingly large wound – through the rubber boot! He (the rooster) also developed a habit of chasing the owner’s two young daughters around at any opportunity.

The other main reason for culling is preventing prolonged suffering among injured or sick animals.

There was a clear dominance hierarchy in this experiment, which is why I merely use it as an example for the process of selecting against aggression (i.e. domestication). I definitely don’t say that this is what we have to do to all animal species we can get our hands on!

In the words of John Gowdy: “Complex societies need simple individuals.”

It makes more sense to talk about a change in brain structure and shape than to only focus on the reduction in overall size or volume, which isn’t even necessarily connected to “lower intelligence” but more to things like the emergence of different abilities or changing scopes of awareness.

Sometimes also depigmentation (think wild pigs vs domesticated ones), but in humans this might invite erroneous extrapolations regarding race. Although from some perspectives it might make sense to think of white people as “more domesticated” than darker-skinned people (historically, at least), while stressing that this does not make one or the other skin tone “inferior” – they are first and foremost adaptations to different conditions. Remember, few other animals inhabit such a large variety of climate zones.

Despite the younger generations’ incessant complains about behaviorally rigid oldtimers, in terms of behavioral plasticity we humans are truly exceptional when compared to most (if not all) other animals. An exploratory phase that lasts only months in wolves – and years in dogs – might stretch up to several decades in us humans.

Creating Diversity is arguably one of the fundamental aims of Life.

But, again, nothing is black and white. It is certainly possible to persuade other animals to perform work for you and carry loads without being violent. If they get rewarded with special meals and have enough time to rest, even draft animals can have pretty decent lives (at least if they don’t require having their spirit broken first, like elephants).

A great book about this topic is ‘Survival of the Friendliest: Understanding Our Origins and Rediscovering Our Common Humanity’ (2020), by Brian Hare and Vanessa Woods.

Civilization just takes those things to new extremes; they’ve shaped human cultures for much, much longer. It seems like primitivism’s main objective should not be to eliminate all potential causes of contemporary society’s excesses (a futile endeavor, since you’d have to “change” some very fundamental aspects of our Nature), but merely to make sure that those potentials don’t become rampant – to maintain a healthy balance, so to speak.

Even among different chimpanzee populations (separated both temporally and spatially), degrees of authoritarianism vary greatly.

Many thanks to Cimbri for pointing out this paper to me!

Remember, traits like propensity towards violence tend to fall onto a spectrum with a normal distribution in any given animal population, with most being somewhere in the center, and fewer individuals on both extremes.

Our recent, climate-enabled (and hence temporary) detour into extreme authoritarian social organizations notwithstanding. It’s merely a blink of an eye in our species’ history.

Evolution is not, as is still widely assumed, driven entirely by random mutations that might prove to be either advantageous or not. The organisms themselves have a lot more agency in the process than we thought.

Say what you want, but I just don’t think humans should wield that sort of power. Take a look at our track record.

I remember the exact feeling, the thrill of being chased minus the fear of being preyed on, that I had so often while playing tag as a child, and I can see that same emotion pulse and twitch through our two young kittens when they’re playing. I know the instinctive burst of courage that drives a hen between her chicks and a potential threat without a second thought, the sheer speed at which we act when a loved one is in danger. I can tune into the mouth-watering excitement of our rabbits when they smell ripe banana, because the same thing happens to me.

Terrific essay, thanks! And in return, here is my thinking. I have posted this Predator's Bargain comment many times in different places, and I suspect many have read it before. However it is still as true today as it was when I wrote it:

--

We have a responsibility to feel love and compassion for the prey animals who are our food. In every instance - grief is the price we pay for love. I once believed what vegetarians and vegans believe now, and while I understand their empathic position, I disagree profoundly with their underlying beliefs. We kill and eat every kind of animal from bugs to blue whales. If T-Rex still existed there would be Dino-Burger stands on every corner and we would swear he tastes like chicken. We need to own this.

All of life - every species - lives on the nutrients supplied by death and the bodies of others. That is a question I have thought deeply about for a long time, many decades. As you may or may not know, I've become a primal eater - my entire diet is meat based, no plants at all, and there are thousands of us who eat this way. So the issue is - what is my responsibility as a carnivore and an apex predator? I'll link to how I arrived at this choice down below.

This is all very interesting to me also because my professional focus is communication, relationships, families, organizations, and communities. I see humans as remarkable community builders - and the best communities we build are multi-species in specific places on the landscape - all kinds of species - bacterial, fungal, plant, animal, and human. When we do this properly it is clearly a complex set of symbiotic relationships that prosper all the species involved including us and the entire ecosystem of which we are a part.

Humans are certainly evolved to be pack-hunting apex predators and obligate meso-carnivores scoring higher on the carnivore scale than wolves for the last 2.5 million years at least, but that doesn't mean we can't be responsible ecosystem engineers building healthy complex communities.

I'm reminded of the predator's bargain that I learned from Derrick Jensen: If I eat a particular animal then I am responsible for its well-being as an individual and as a species. My food must live a satisfying life of dignity in the full expression of its nature. It must be treated with respect, and I must pay attention to the health and diversity of its habitat. I must do everything in my power to protect and defend that species as an integral aspect of my own healthy community, especially because the lives and health of those animals in their natural environments are not separate from my own.

If you look closely at the work of folks like Allan Savory, Joel Salatin, and other regenerative farmers who have fully integrated animals into their practice - notice their pigs, cows, rabbits, chickens and so on - they all live lives in the full expression of who they are as animals - expressing the pigness of a pig, the chickenness of a chicken. Just by living that natural life they accomplish much of the work of the farm. They are healthy, happy, they live a good life and they are killed quickly in a way that does not stress the animal.

The exemptions are for animals that are working partners, so dogs, cats, horses, the occasional truffle-hunting pig and many other kinds of animals where we develop unique relationships - they all should get a free pass and be well-cared for too - treated with kindness, affection and respect.

To ignore the cycle of life and death is an ideological pretense that removes one's self from the world. Every living being acquires the essential nutrients of life from the death of the bodies of others, whether a bacteria, a fungus, a plant, an animal. We need to own the violence in our predatory nature and take real responsibility for it.

A Hunter's Prayer

Thank you, little brother, for your strength which will be given to my family.

Thank you for making life for us possible.

Thank you for your love.

Go and wait for me at the door of the spirit world.

I will be along fairly soon.

And we will be together again.

--

I agree with this view. Thanks for posting this.