Escalating Conflict: A Symptom of Systemic Collapse

The final chapter of Global Civilization begins... --- [Estimated reading time: 30 min.]

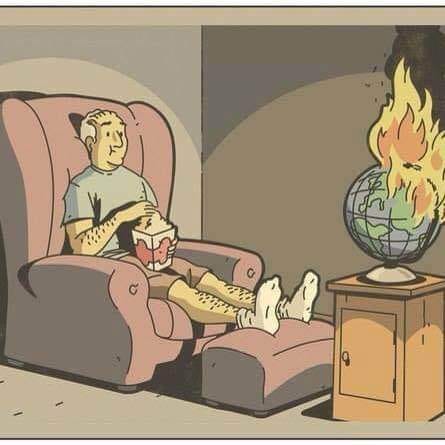

As anyone who has as much as casually scanned the headlines or scrolled the Feed during these past few years can confirm, it would definitely not be an overstatement to say that the world is becoming more chaotic by the month. Worse still, it is also becoming more violent. Armed conflict is on the rise, and, thanks to digital technology, we’re all closer to the action than ever before. If the algorithm senses even the remotest relevance, we’re now regularly exposed to combat footage, raw and uncut, right on our screens. Increasingly, the same gadgets and apps delivering anxiety and existential dread straight into our living rooms now also shape the development and outcome of those conflicts.

A few years back, right after Myanmar’s civil war broke out in early 2021, the first shaky videos of armed clashes started flooding Southeast Asian social media channels. I remember telling my wife that the scariest thing for me is that the setting of said videos looks pretty much exactly like Thailand, our home. Like it could happen here.

The scenery always seems eerily familiar. Dogs idling in the shade of majestic Bodhi trees towering over a gold-plated temple compound. Next to it, a scenic village with tin-roofed wooden huts and flocks of chicken darting back and forth between the dwellings and home gardens. Dusty, reddish-brown dirt roads lined with coconut palms and clumps of bamboo, and, blanketing the mountains in the distance, plenty of thick, green jungle in between.

Then the old pickup truck from which the video is being filmed slows down, and the camera reveals the payload concealed in the vehicle’s bed: dark-skinned, barefoot fighters – many of them younger than me – huddled together, hidden from view, hugging their automatic rifles. The truck comes to a halt right next to a small checkpoint manned by unsuspecting uniformed soldiers, most of them resting in the afternoon heat. After an instant of tense silence, all hell breaks lose. Accompanied by unintelligible war cries, the young men don’t stop until they’ve emptied their magazines, leaving the checkpoint and its occupants riddled with bullet holes.

The soldiers of Myanmar’s various rebel groups, most of them born around the turn of the millennium, have long understood the importance of social media in modern conflicts. They make sure there is always dramatic combat footage of their bold forays against a seemingly superior adversary, the Tatmadaw – Myanmar’s highly influential military elite – as well as evidence of the junta’s ruthless targeting of civilians and indiscriminate aerial bombing campaigns. Public perception influences outcomes.

The ubiquitous smartphone has become an important instrument of war.

All this is happening right beyond Thailand’s western border. At times, people could hear the rattling of the rebels’ machine guns and the roaring of the jets employed by the military. Recently, stray mortar shells landed on the Thai side, injuring civilians and damaging structures. It was close enough to raise eyebrows, but still distant enough to not cause any serious concern. After all, this was an internal conflict that was unlikely to spill over into neighboring countries.

But now trouble is brewing at Thailand’s eastern border as well, creating a volatile situation that mirrors the current zeitgeist and similar social and political developments all over the world.

“Civilizational collapse will manifest as a series of armed conflicts viewed through phones with footage that gets closer and closer to where you live until you’re the one filming it.”

This spontaneous alteration of the memorable climate change awareness social media campaign by Greenpeace Thailand1 shot through my head a few months ago,2 when the first images of the renewed border clash between Thailand and Cambodia started circulating, first online, then soon after in the news.

I remember thinking: this is getting pretty damn close.

Our home is about 25 kilometers away from the border – as the hornbill flies – with nothing but thick jungle in between. Fortunately, there hasn’t been any fighting in Chanthaburi (the only border province spared so far), but we’re close enough that, on some nights, we can hear the distant rumble of the artillery in Sa Kaeo, the province to the north of us. In addition, the Royal Thai Army has ramped up drills and target practice for the big guns in our province, so their presence makes itself felt, even more than usual.

It is still not entirely obvious why exactly Cambodia seemed so keen to help escalate the border conflict that finally reignited this year, after a period of eased of tensions that lasted over a decade. The smaller of the two Kingdoms is not only vastly outnumbered, it’s hopelessly outgunned. Their lack of an Air Force presents a major vulnerability against Thailand’s fleet of high tech fighter jets. Much of their equipment is Made in China, and especially larger machinery often consists of old Soviet models, an inheritance from the Red Khmer. They have fewer strategic alliances, and their strongest military ally is China.

But Cambodia’s leadership shows fanatic determination, and – until now – they have most of the public behind them. How far will Hun Sen (who ruled the country for over three decades, and is currently still president of the Senate) go to prove to the public that his son is a worthy successor, and not yet another high-profile case of blatant nepotism?

To be honest, a rapidly escalating armed conflict between Thailand and Cambodia wasn’t on my 2025 Collapse Bingo card. I was vaguely aware of the underlying issue – a territorial dispute involving a few ancient temple ruins that both sides claim are of cultural relevance to them – but had never heard it mentioned publicly before earlier this year, when provocations began. It is often unclear which side initiated each consecutive escalation, but any attempt to answer this question appears equally pointless as trying to determine who started a squabble between siblings.

I won’t bore you with the details of how the current dispute originally started (when, over a century ago, a colonial power drew arbitrary lines onto a map3) but a rough outline of recent events leading up to the outbreak of hostilities might read like this:

A group of Cambodians wanted to sing patriotic songs at one of the disputed temple sites (which were, obvious to any outside observer with even the scantest architectural perception – i.e. eyes – clearly built by the Khmer), and Thai soldiers intervened. Some Cambodian civilians shouted insults at Thai soldiers (and vice versa), igniting heated debates on social media. One day, a scuffle erupted between two groups of soldiers, fists flew. More skirmishes followed, and in the ensuing chaos a Cambodian soldier was shot. Mysteriously, Soviet-made anti-personnel landmines suddenly appeared in an area that was supposed to be long cleared on the Thai side of the border. Several unsuspecting Thai soldiers on patrol have been wounded since.

And then, one day, when we stopped at a friend’s house in the valley on our way to the experimental communal rice plot, news broke on TV that areas of Surin province had been hit by Cambodian artillery. On the screens, shaky footage of burning buildings and screaming people. In the following hours, as we worked the hillside field above the scenery, nervously scanning the Cambodian border on the horizon every few minutes, the village below lay eerily quiet.

In the days after – just like during the early days of the Pandemic – life periodically felt “like in a movie,” a feeling that sometimes indicates witnessing a historic moment to be recounted for years to come. It felt strangely banal, yet slightly surreal; I vividly remember a smiling old woman selling fried bananas from her roadside stall while a long convoy of military vehicles rattled by.

Meanwhile, martial law had been declared for several districts in two provinces on the Thai side, including ours. All of a sudden we found ourselves living in an “active conflict zone” – yet life went on pretty much as usual.

The first thing we noticed was the visible exodus of Cambodian workers, and, of course, a lot of troop movement. We live in a highly militarized province, and ubiquitous army presence is the norm for us, rather than the exception. Checkpoints, bases, as well as vast training areas and shooting ranges have been clustered here since the days of the Vietcong and the Khmer Rouge.

Like my own native country, Thailand was once a “bulwark against communism,” which leaves unmistakable cultural marks due to the often subliminal influence and interference of the anti-communist “World Police”4 (who also supplies plenty of arms and ammunition).

As a result, it is not unusual for us to see tanks or artillery destined for field maneuvers parked temporarily along the highway down in the valley. But recently there have been a lot more military vehicles, especially unmarked civilian trucks with cargo beds wrapped in green tarp (probably transporting ammunition) – harbingers of death and destruction.

When my wife’s younger brother served in the Thai Marines, he was, by chance, stationed at a firing range just outside the other end of our village for the annual artillery drills. As every year, we could hear the blast of each round being fired loud enough to scare up the birds. Down in the village the shock waves rattled windows and were intense enough to make you startle anew every time, even if you knew they were coming – for almost a week.

A quick online search at the time revealed that each standard Howitzer round costs around 1,000 USD – approximately 35,000 THB – more than the average Thai household’s monthly income, pulverized in a cloud of dust and smoke, every fifteen minutes.

One might be tempted to call this a truly appalling waste of money and resources that would be dearly needed elsewhere. But the nation’s priorities are set.

For the sovereignty of the Thai territory!5

It’s not like there is a shortage of other problems, in either of the two countries. Apart from drawing on the same cultural legacy, they also share rampant corruption, widespread cronyism on every level, rapid environmental degradation, and a private debt crisis of such enormous proportions that non-performing loans alone could soon topple the economy.

Both countries are far from “democratic,” and have been largely ruled by the same two clans6 for decades. In Cambodia, starting an oppositional party is not even an option, whereas in Thailand any party opposing traditional elites is swiftly and conveniently made illegal, if necessary even after they gain the majority of votes in the national election.7

On both sides of the border an economic crisis of unprecedented proportions unfolds, and all the while inequality is still soaring to record levels.

A few days into the conflict, the Cambodian army attacked Thai navy vessels in Trat province (south-east of us), so it seems the conflict is at least in part about the disputed offshore oil & gas field in the Gulf of Thailand as well. Estimates show that the field holds reserves equivalent to about one year of current Thai consumption levels, a drop of water on a hot stone, but it seems nobody is even thinking that far anymore. I’m dead serious: none of the leaders seems to have a long-term plan, and I doubt even their collective attention spans would allow for such cognitively demanding feats. Not even the elites are safe from the Great Stultification, the digitally-driven devolution of the human race. Brain rot is contagious.

Idiocracy is the hallmark of the Moronocene.

Thus it appears that, once again, the old guard manages to prevail, both in Thailand and Cambodia. And, once again, they successfully employ the most ancient play in the history of politics: if things are falling apart, the economy falters, people lose hope for a better future, and uncertainty looms dark – point at your favorite archenemy and blame them for it.

The necessary social prerequisites had been cultivated over centuries.

For years, bored “netizens” have battled each other verbally and with vulgar memes in various ASEAN online forums and Facebook groups, coining terms and phrases such as “don’t Thai to me” and “Scambodia” that have since been plastered over the comment sections of every newspaper article even remotely touching on bilateral relations.8 Most of it could previously be dismissed as crude (but harmless) teasing, but once people started dying, things took a more sinister turn. All of a sudden, this continued mutual vilification was brought out into the limelight.

What has proven itself to be an immensely destructive force historically is accelerated even further in the digital age. Suddenly, the proverbial weird uncle or aunt spouting chauvinist platitudes and spreading xenophobic rumors had an online audience of seemingly unlimited dimensions. Millions of people could be reached if what you said was just outrageous enough. Intending to “go viral” and “defend their country’s honor,” many already terminally online young urban professionals with rudimentary English skills and boring office jobs fanned the embers of a culture war that had been smoldering (and had periodically blazed up) for ages. Soon, social media accounts specifically targeting the other side proliferated, drawing on two of the most engagement-facilitating emotions: anger and fear.

Of course, the people behind those accounts make up a small proportion of each country’s population. But their near-constant online activity (coupled with a hefty boost by the Algorithm) makes it seem like they represent a sizeable part of the population, perhaps even a majority. And, as is usual for collectivist cultures, general public opinion soon followed along, as dissent vanished.

This same dynamic was at play when Myanmar’s junta carried out its clergy-sanctioned genocide against the Rohingya, and the same baby-blue, supposedly “social” network allowed Sri Lankan fundamentalists to spread propaganda that incited deadly violence against their Muslim neighbors. As is usual for corporations, Facebook initially rejected responsibility, but later apologized after public pressure mounted.

Yet just a few short years later, the exact same thing is allowed to happen again, in a different corner of the region. Truth be told, any attempt to stem the tide of online hate would be a Sisyphean task, a mission as boundless as the Feed itself. No, the genie is out of the bottle, and reigning it in now would be like trying to sieve the microplastics out of the ocean.

On grounds of “free speech” (and to kiss Trump’s ass), Facebook has since rolled back its fact-checking efforts, allowing misinformation to spread virtually unchecked, especially if it’s in other languages.

Meanwhile, generative AI has turbocharged the raging meme wars, and an astonishing number of digitally illiterate people in both countries are unable to differentiate between AI-generated images and real photos.

We continue to inhabit the same physical world, but each subgroup (and subculture) creates their own feel-good interpretation of reality, thus constructing increasingly incompatible worldviews so dramatically disconnected from one another that reconciliation has become impossible. Rational, calm debate is simply not an option anymore, whether we’re talking about the MAGA mob or its Southeast Asian equivalents.

The sheer speed at which this cultural fragmentation and concomitant enshittification of public discourse takes place right in front of my eyes is terrifying. Social media feeds – a major source of “news” in Southeast Asia – are clogged with misinformation, graphic combat footage, AI slop, and blatant propaganda. And with an estimated average daily screen time of around eight hours, much of the Thai (and Cambodian) public is now constantly exposed to Orwell’s “Two Minutes Hate” on continuous playback, creating a positive feedback loop of humanity’s ugliest sides that stretches as far as you can scroll.

I maintain that this entire conflict would have never happened if it wasn’t for social media.

The thing that frightens me the most is not the Cambodian army (let alone poor migrant workers), but the attitude of the majority of people in our area, and even among our friends & acquaintances. Neighbors didn’t send their kids to school because they were afraid that it might be targeted, as if Cambodia would dare shelling a provincial capital. People suspiciously eye anyone who doesn’t look familiar, especially if they have darker skin. Viral posts by dubious nationalist pages warn of Cambodian spies, and every immigrant taking a picture in public might scout for new targets – the notorious “enemy from within.” There have already been rumors9 of secret terrorist plots to “carry the fight to Thailand,” and, perhaps as a result, of mob violence against random migrants (which might be true or not). During the first round of clashes there was even a uniformed and (partially) armed volunteer group10 patrolling the roads, as if Cambodian guerrillas could come straight out of the forest.

Talk about manufacturing threats…

People whom they have lived alongside with for decades are suddenly ostracized. (Remember, the whole thing started with territorial disputes around temple sites!) What we are witnessing here is the exact same mentality that, if unchecked, ultimately ends in mass violence, perhaps even genocide. Almost ninety years ago, the same underlying social and psychological dynamics were at play during the pogroms in Nazi Germany, when ordinary people enthusiastically participated in the demonization of their neighbors and the destruction of their property.

Generally speaking, nationalism is the ideology of the ignorant. Anyone who has had the chance to widened their horizon through reading, travel, or intercultural exchange quickly realizes that no nation is inherently superior to any other. All societies have their own particular advantages and drawbacks, and each country has roughly the same set of people. Rich and poor, selfish and generous, dumb and smart – and everything in between. Historically speaking, pretty much all modern nation states have committed their fair share of atrocities, although those are often filed in the back of the cabinet in favor of more flattering narratives. Some countries had bad luck, while others fared better, often for rather arbitrary reasons long predating the generations experiencing the aftermath.

But that, apparently, is too much nuance for the simultaneously overwhelmed and underutilized brain convolutions of the common man.

I am dumbfounded by how many people, some of whom I’ve known for years, openly spoke up in favor of indiscriminately deporting everyone of Cambodian descent. A staggering number of Thais support building a border wall between the two countries. Yes, a border wall. And those from ultra-conservative and/or military families wouldn’t mind if Cambodia was completely overrun by Thai forces in a swift blitz. For King & Country!

For the general Thai public, there is no war in living memory in which the nation was directly involved. Thailand had violent conflict, terrorism, and various coups, uprisings and insurgencies, but people didn’t have to flee their homes en masse, and they certainly haven’t been bombed into submission – unlike with some of their neighbors, the infamous “shock and awe” experience is lacking from cultural memory. In Thai schools, as elsewhere in Southeast Asia, historic warfare is still often taught in a blatantly one-sided and shamelessly glorifying manner (and with vast factual inconsistencies between countries) that downplays or completely ignores the significant human cost and perpetuates stereotypes.

For me, the rampant militarism here is alarming. Irrespective of popular euphemisms, soldiers are, first and foremost, trained killers protecting and advancing the interests of the elites.

In my native country, for instance, recruitment campaigns by the Army that target schools are regularly protested and criticized.11 Here in Thailand, military units visit schools every year on “Children’s Day” and elementary graders get to hold machine guns and sit in armored vehicles. Students of all ages regularly march around in uniforms, and every morning the entire school spends half an hour raising the flag and singing the various anthems.

The universal acclaim with which the military is regarded is deeply disconcerting to me. Despite reoccurring scandals, violent hazing, persistent reports of sexual abuse and rape, physical punishment amounting to torture, and mysterious deaths among recruits, being a soldier in the powerful (and notoriously top-heavy) Royal Thai Army – itself a major political force – is still considered a source of pride.

Recently, I’ve witnessed an attitude of what can only be described as excitement for war among some parts of the population that reminds me of pre-WWI Europe, often expressed with varying degrees of privacy (or publicity) on social media.

Fellow villagers publicly post comments like “Shoot them all” on social media, and time and again one encounters the same rhetoric questions – “What are we waiting for?” or “Why not finally get it over with?” – implying what exactly? The annexation of Cambodia into the glorious Kingdom of Siam, once more? The wiping out of the hated Khmer?

The dangerous thing is – and I’m speaking as an immigrant here – you never know who the next victim will be. Hopefully (?), the Thai public won’t target Germans anytime soon,12 but you don’t have to be of a certain ethnicity to find yourself in the crosshairs – it is enough to be perceived as “other,” or even to speak out in defense of a perceived outgroup. From the beginning on, moderate voices have been unanimously labeled as “Cambodian at heart” (หัวใจเขมร) by hardliners, and Thai PM Anutin Charnvirakul, himself staunch royalist and adamant supporter of the military, has repeatedly made it clear how little he regards the opinion of “foreigners” on the conflict.13

For the moment, few people are bothered, let alone alarmed, by the recent developments. Bolstered by their military and technological might, a growing part of the Thai populace is out for blood. In the media every fallen soldier is extensively (and repeatedly) profiled in the most intimate detail possible (complete with minute-long video clips of sobbing relatives), while “enemy casualties” are presented as a number, a score – the higher, the better.

In authoritarian collectivist societies nationalist sentiment can escalate rapidly into ethnic cleansing, as has happened repeatedly in recent Southeast Asian history.

At first, it looked like Cambodia had squandered their chance to gain underdog sympathy internationally, partly due to the obvious lies that were being spread by the highest levels of governance and the brazen actions by its military.14 With visible satisfaction, Thailand got to play the role of the “grown-up” during the first exchange – which, thankfully, included exercising a lot of restraint in the face of continued provocations – but that restraint has since turned into gleeful malice. Give any military more power, and it will use it to advance the things it trains for. With pride, our current (temporary) prime minister has repeatedly stated that he has no control over the actions of Thailand’s armed forces, and that he doesn’t deem it necessary to attempt to reassert it – he has “full trust” in the military.

As a result, for the past few weeks Thai F-16 and Gripen jets carried out numerous near-daily bombing campaigns deep into Cambodian airspace – the Thai news report exclusively on precision strikes against military targets, while Cambodian news exclusively shows damage to schools and residential buildings.

Internationally, Thailand is increasingly seen as the aggressor, which visibly irritates a Thai public that has been brainwashed into believing that their military only destroys enemy fortifications and doesn’t target civilians; it’s always “the other side” that takes innocent lives.

Both sides appeal to the “international community,” which in turn finds itself bogged down by numerous other interconnected problems and crises, both at home and abroad. Apart from “strongly condemning” the aggressions there is very little that most countries can do, especially if there are conflicts of interest with various economic superpowers involved.

And, as always, we have to ask the most crucial question: cui bono?

Apart from the established political elites on both sides who can temporarily distract their citizenry from mounting internal problems, the rising colonial power towering in the background eagerly rubs its hands. China sells arms to both countries and stands to profit from regional instability in the same fashion as it does in neighboring Myanmar.15 Sell weapons to both sides and support whoever is winning, in exchange for minerals, materials, and access.

Just days before the first round of fighting broke out, a large shipment of BM-21 rockets and artillery shells from China arrived in Cambodia.

When two people quarrel, the third rejoices. Instability and chaos means less attention is being paid to anything else, like the colonization of poorer countries through loans (i.e. debt) for infrastructure projects as part of the Belt and Road Initiative, and the concomitant quiet takeover of crucial industries, infrastructure and land by Chinese “investors.”

In the midst of chaos, it seems, some sense opportunity. (I wonder who said that.)

Very similar scenes unfold in other parts of the world, where old rivalries flare up and new conflicts ignite as population pressures mount and the struggle for the last remaining resources intensifies. Israel and Palestine (and much of the Arab world), Pakistan and India, India and China, China and the US, the US and Russia, Russia and Ukraine, not to mention a dazzling array of wars and ethnic conflicts on the African continent – and the list is only getting longer.16

Finally, we’ve reached the top of the steep mountain pass road traversing Peak Oil, and gradually Peak Copper17 comes into view, while Peak Steel and Peak Farmland are already in the rear-view mirror. Major superpowers are panicking,18 scrambling head-over-heels to secure their standing in the rapidly shifting global hegemony that, as Nate Hagens never fails to remark, has come to resemble a game of musical chairs – in which Thailand is eager to secure its seat, even if that means the elimination of its neighbor’s.

Conflicts like this are a symptom of overshoot and collapse. War has played a decisive role in most historical instances of societal collapse (together with climatic fluctuations, overexploitation of crucial resources, pandemics, shortages and famines, all of which we’re witnessing now), and ours will be no different.

The dominant culture’s chorus of optimists has long tried to claim that war is largely “a thing of the past,” but it is increasingly becoming clear that history moves in cycles.

Pretty much everyone (except a few very privileged and/or ignorant people) slowly starts realizing that the future looks rather bleak, and that the Myth of Progress promising sci-fi technotopia was nothing but an elaborate lie, repeated over and over again to keep us toiling and consuming. We’re riding the downslope of this civilization’s bell curve, as I always say, and we can clearly feel the acceleration by now.

Fasten your seatbelts and brace for impact.

The thing is, I’m not even a “pacifist.” I do think violence is sometimes justified, useful, at times even necessary.19 Violence – and, by extension, war – is a common natural response to overcrowding and/or increased competition for limited resources, not only for us humans but for most other animals as well.20

“World Peace,” a world without any violence or conflict, is (unfortunately, I might add) a naïve, ultimately unattainable fantasy.

Contrary to popular opinion, conflict didn’t decline (slightly) in the second half of the 20th century because we as a “global society” suddenly realized that “war is bad,” but because of nuclear deterrence (i.e. mutually assured destruction), and because the unprecedented energy bonanza after WWII meant there was less direct competition for resources and more abundance for everyone. We could exploit Nature instead of each other, and use “energy slaves” instead of human ones to “raise our standard of living.”21

Quite predictably, this Age of Abundance has come to an end. From now on, there will be ever fewer resources to spare and ever more hungry mouths to feed, as countries compete for dwindling resource stocks, creating the perfect breeding ground for social strife and war.

In this set of circumstances, as much as it pains me to say that, conflict is inevitable.

We are primates. When we fight with siblings, spouses, friends or strangers, the exact same psychological mechanisms22 play out that have shaped our ancestors’ relationships for millions of years, accompanied by a uniquely human barrage of complex strings of vocalizations meant to persuade, ridicule, intimidate, subdue or silence the opponent. We might find abstract and lengthy justifications for our violent outbursts (and our wars), but on a deeper level they are almost always caused by something much simpler: selfishness, fear, jealousy, (perceived) unfairness, or feelings of neglect, insult, or inadequacy (among others).

This underlying “biological programming” influences social relations on the group level as well: when, for instance, a group of chimpanzees hears the cries of another group from beyond the border of their territory, they fearfully embrace the group’s alpha – just like, in times of outside threats (real or imagined), human societies tend to seek out strong leader figures.23

And when two groups of primates clash, be they human or chimp, the same basic forces are at work: reason, empathy and long-term thinking are temporarily sidelined, and the more ancient parts of the brain take over. Rage and bloodlust rule the battlefield.

Violent clashes, territorial disputes and border skirmishes are as old as humanity, perhaps as old as complex life itself. There were occasional clashes between different groups in the long and rich history of our species, and although they dramatically intensified with the adoption of agriculture, for most of human history the low population density and the vast open areas devoid of humans meant that such conflicts were the exception, not the norm.

Unfortunately, current population levels (and resource pressures) make some form of imminent reduction in the human population24 inevitable. The Thai-Cambodian border conflict is merely a foretaste of what’s to come, one fractal snapshot of the increasingly precarious global situation.

The big difference between primitive and modern warfare is that the former is generally not geared towards senseless destruction and the extermination of the enemy; it is more saber-rattling than carpet-bombing.

Arrows are aimed in the general direction of the enemy and fired at will (and not in much more efficient volleys), without even attempting to inflict maximum casualties.

As Daniel Quinn so convincingly argued in My Ishmael (1997), the goal is to show ones strength and readiness to defend oneself, thus forestalling the unchecked expansion of any one group (and undoubtedly also to have exciting stories to tell about ones heroic battle experiences).

In short: it tries to prevent the very conditions (i.e. hopeless overshoot) in which we find ourselves trapped in today.

Although I would never take up arms to fight in a conflict between modern nation states (and I would flee conscription if that threat ever materialized), I could see myself getting excited to partake in such a primitive battle – given it’s not too common of an occurrence! – especially so if I would be part of a tight-knit social group that takes care of me, a community worth defending.

But are a few moldy, overgrown old temple ruins worth defending, worth dying for? They are of absolutely zero importance in the day-to-day lives of citizens in both countries, mere tourist attractions, and if it wasn’t for social media virtually nobody would know (or even care for) what was going on there.

Of course, if we carefully peel back the layers of abstract justifications, the actual reason why so many people enthusiastically support this conflict (and welcome its escalation) doesn’t have anything to do with those ruins. It’s about something much deeper: a simmering feeling of desperation. It’s about the crushing uncertainty about the future and the concomitant loss of hope. It’s about hardship, frustration, alienation and anger, without any immediately obvious release valve.

Food prices are rising fast, as is the general cost of living. Good jobs are harder to find, and the long trend towards upward social mobility has been reversed. Completely lacking sufficient knowledge of the broader historical (and economic) context, all that the masses know is that things are getting worse, and if you give them a scapegoat for their woes they’ll readily tear it to shreds, without as much as a second thought. Nationalism provides a feeling of unity and solidarity, of group identity and shared goals, albeit on an abstract level – a “toxic mimic” of small-scale community cohesion and familiarity that contemporary society so dearly lacks (and that imperialism/capitalism so eagerly destroys).

History rhymes, and the echoes will reverberate for quite a while before finally fading.

For the past few months, a shaky ceasefire was in effect. But, as I’ve predicted, it ultimately didn’t hold.25 Current rhetoric mirrors the right-wing populist wave surging the globe, and hence makes further escalation ultimately inevitable. It has been said that social control is best managed through fear, and in these turbulent times any distraction from mounting internal issues is welcomed by those in power.

In addition, stoking nationalistic fervor is an easy way for conservative forces to win votes for the upcoming election this February. All the prerequisites for renewed clashes and a protracted, simmering conflict (which ultimately wouldn’t end well for Cambodia) are present, but there is no telling how long it will drag on.

Things might even quiet down again for a while,26 but the smallest spark could reignite it anytime.

The immense damage to society, the economy and the environment, however, is already starting to show.

On the Thai side there is a massive labor shortage unfolding, because most remaining Cambodians left the country when rumors (of unknown origin) circulated online that every land owner who doesn’t reside in Cambodia will be disowned, causing scenes of disorder and desperation at border checkpoints. The economic, political and social chaos on the Cambodian side is even greater. Almost one million migrant workers have returned to a struggling country utterly unprepared to incorporate them immediately, tens of thousands of civilians had to flee their homes, and a humanitarian crisis on scales not seen for decades is unfurling in front of our eyes.

At the same time, the forest connecting the Wildlife Reserve beyond our garden to the Cardamom Mountains on the Cambodian side was fragmented by a hastily built dirt road, again for “national security” reasons (and definitely not, of course, for the enrichment of the machinery’s owners).27 The proposed border wall – if ever realized – would prove even more harmful for migrating animals and wildlife in general. Vast tracts of forests and farmland have already been destroyed and polluted, countless wild animals have been killed and displaced by the fighting, and Cambodian media reported that a female elephant and her calf were killed by shrapnel.28 The huge environmental cost of war is often neglected, but represents yet another stressor on ecosystems already stretched to the limits of their integrity.

Things are looking bleak; indeed, bleaker than ever before.

All of a sudden, the unthinkable becomes possible. Yes, a war might break out, right here, where we live. We are not safe from it. And this leads to another realization: owning land and planting crops doesn’t necessarily increase your chances of long-term survival. What would we do if fighting spilled over into the region we call home? At what point would we consider leaving behind everything we’ve built? And where would we go?29

There is a certain incredulity, a sense of ‘is this really happening right now?’ that takes you by surprise, even if you knew it would happen eventually. It is widely known that the UN expects the number of refugees fleeing war and disaster to soar in the coming decades. Will we one day find ourselves among them?

This same unease and anxiety is now felt by people in overdeveloped countries, for many of whom it is an entirely new sensation. Suddenly, German media advises citizens what to do when they hear the air raid sirens, and how much supplies to stock at home.

Authoritarianism, militarism and protectionism are on the rise globally, and at a time where there is no shortage of pro-social and ecological projects worth financing, the best thing economic and political elites can think of is building bunkers and stockpiling more guns like some paranoid prepper.

To our great misfortune, in our atomized and alienated global society uncertain times breed distrust and selfishness, even though what would be needed most is empathy, mutual aid, cooperation and the realization that all our fates are entwined. There will be no “winner” here, not even the billionaires, and certainly not any single nation.

It will take a while until the majority of people realize that the current crisis is not merely a temporary bump on our journey to the stars, but permanent – I’ve been told that the term “permacrisis” is on the rise in Europe – and getting worse by the year. This is evident in increasing nostalgia for a bygone era of abundance and optimism, and this longing for the “good old days” is a major driver of the new wave of conservatism, protectionism and nationalism surging the globe.

But once the masses do realize this general trend, new conflicts will sprout up like mushrooms after a rain.

Things will get a lot worse before they get better.

Regrettably, civilizational collapse as an abstract concept and overshoot as its underlying driver will never be obvious for most people in this world. Instead of realizing that there really is nobody to blame (except perhaps our own ancestors, who – in their defense – acted more or less unwittingly), they will remain prone to conveniently blaming their least favorite outgroup, exacerbating social tensions already stretched to breaking point. For the vast majority the (variably) “long descent” will materialize first as economic hardship, and then as unrest and conflict, accompanied by a long recession from which the country ultimately never recovers. We’ve already endured years of economic hardship, and the recent uptick in violent conflict is a sure sign that collapse is reaching the next stage.

It won’t be pretty.

Regarding the Thai-Cambodian border conflict, objectively the “least bad” thing that could happen now would be a sudden & drastic rise in local energy prices (and hence availability), perhaps due to new (proxy-)conflicts between superpowers trying to monopolize as much of the remaining global fuel supply as they can. This would force people to localize and deindustrialize essential supply chains (first and foremost the food system), similar to what happened to Cuba after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Both countries have the advantage that about a third of the workforce is already engaged in agricultural labor.30 If people are busy growing food they have less time to scroll social media or slaughter each other. Fuel shortages, if severe enough, would instantly turn tanks, fighter jets, battleships and other war machinery into useless chunks of steel, and prioritizing defense over agriculture would be an extraordinarily stupid (and short-lived) strategy, even by local standards.

But as of now it seems that all this might take a few more (and increasingly painful) years.

Again, there is really nothing we can do to stop any of this, or at least not anymore. The forces at work here are far beyond anyone’s control. I would like to end this essay with some solid advice or a hopeful note, but, again, I have neither. Things are gonna get real ugly, real soon. Even the lushest garden is useless if you face displacement, staying off social media won’t make a difference if everyone else is still constantly online, talking to people has become effectively impossible because we inhabit different realities, and basic cognitive functions continue to atrophy rapidly in an ever-growing part of the human population.

As the collective face of the dominant culture slowly twists and distorts, from worry, to anger, to agony, the AI-generated grin on its digital death mask grows fainter by the day.

Collapse is here, my friends, and from now on armed conflict will be a constant companion for ever more of us.

The only way out is through.

I write stuff like the above in my free time, when I’m not tending the piece of land we’re rewilding here at Feun Foo. As a subsistence farmer by profession I don’t have a regular income, so if you have a few bucks to spare please consider supporting my work with a small donation:

If you want to support our project on a regular basis, you can become a Patron for as little as $1 per month - cheaper than a paid subscription!

The original quote is “Climate change will manifest as a series of disasters viewed through phones with footage that gets closer and closer to where you live, until you’re the one filming it.”

I initially planned on publishing this piece back then, but put it on hold after a ceasefire agreement was negotiated just before I could finish it. With the second ceasefire now still in effect, I’ll just publish it anyway.

Or when Cambodia effectively became a vassal state of Siam in the 19th century, or when the Siamese sacked Angkor in the 15th century, or when Siamese troops first occupied the capital in the 14th century, and so forth and so on… The feud has been going on for quite a while.

The United States funded a good deal of right-wing activity during the Cold War.

This slogan (lit.: “เพื่ออธิปไตยของแผนดินไทย”) is the new battle cry (and ultimate justification for Thai military aggression) uttered by every politician, military official, news spokesperson and proud nationalist alike.

I almost wrote “ruled by the same clowns” – Thaksin Shinawatra and Hun Sen.

As was the case in the 2023 general election, when discontent among the younger generations led to a record voter turnout of over 75 percent and the creation of an entirely new political force in Thailand: The (center-left) progressive “Move Forward Party” (rebranded after their first iteration, the “Future Forward Party” was made illegal three years earlier) gained the majority of votes, yet was prevented from forming a government when military and royalist elites realized that they might enter a coalition with the traditional populist “Pheua Thai Party” of the Shinawatra clan. Move Forward campaigned on the abolition of both mandatory military service and the draconian lèse-majesté law that severely punishes all criticism of the royal family. (It has since been reestablished as “People’s Party” – the game continues…)

It has gotten so bad that many news websites now automatically geo-block IP addresses from the other side.

To make matters worse, FOX News pales in comparison to most major Thai TV media outlets, with an obsessive focus on crime and violence, homicides, thefts and other scare stories that paint the outside world as threatening and in need of a “strongman” government enforcing law & order.

Called ชรบ. (ชุดรักษาความปลอดภัยหมู่บ้าน - the “Village Security Guard Unit”) in Thai.

As I always say, we have a little history with militarism.

Perhaps a wild guess for my 2026 Bingo Card?

Anutin denied having agreed to a ceasefire in a phone call with Trump and said he is not concerned by potential tariffs.

Everyone who is laying anti-personnel landmines has lost my sympathy.

How nice would it be for China to have a deep sea port right in the Indian Ocean, instead of having to circumnavigate the Strait of Malacca.

“The US and Venezuela” was added just a few days ago.

Peak Copper will be the final blow to those still believing that “electrification” will “save” us.

The massive rollout of “renewable” energy in China is not a monument to their love for the environment or their concern for the world’s climate, it’s a knee-jerk reaction to the frightening reality of a world past Peak Oil.

Two excellent pieces that align with my stance are Jessica Moore’s Demonizing Violence Alienates Us From Life and Arnold Schroder’s It isn’t nonviolent to let people hurt you.

This is most certainly not a “good” thing, and I can’t say that I particularly like this fact (I would personally prefer words over weapons whenever possible). But, in Arnold Schroder’s words, it seems to be part of how the world works, so we’d do better integrating this uncomfortable truth into our worldview and seeing what possibilities exist from that point.

Coincidentally, a “high standard of living” means living a bit like a modern-day feudal lord or lady who never has to do physical work or chores.

If their enclosure happens to have one, angry chimps in captivity are even known to slam doors to express their frustration.

This is partly why so many North Americans fearfully embraced Trump – admittedly not the best example for a “strong alpha male” – in face of a perceived “outside threat” (immigrants).

Either due to armed conflict, famines, deteriorating public health, or a steady decline in birth rates – or any combination of those.

A newly negotiated ceasefire came into effect right before New Year, but Thailand has already claimed the Cambodians repeatedly broke it, and – again – I feel confident in predicting that, ultimately, it won’t last.

It seems like for the moment the public’s attention has (temporarily) shifted to the next big spectacle: campaigning for the national election next month is in full swing, and the topic dominates news and public discourse.

The project was spearheaded by well-known and influential local leaders, who incidentally also own heavy machinery (and perhaps lack contracts during the protracted economic slump). Over two million Baht in donations were extracted from unsuspecting “patriotic” citizens by utilizing nationalist rhetoric to stoke fears. Cambodians?! Shut up and take my money!

It’s impossible to verify this claim.

So far, there is no reason to believe that any of this might happen anytime soon, but the novel situation naturally sparks such uncomfortable questions.

Many of the major cash crops currently grown – sugar cane, palm oil, rubber, etc. – are rather useless in such a situation, but there is much greater (theoretical) potential for resilience than in overdeveloped countries where farmers make up only a few percent of the population.

I sympathize with your experience.

In fact, in Cambodia and Thailand, everything is not so bad yet. It is a real hell when there is no way out, and you are a rat in a cage that is lowered over the fire. As soon as you hear about plans to expand the existing army, leave without thinking, because then the exit may be closed. Do not think that the conflict will stop with rising prices and fuel shortages. On the contrary, everyone who cannot work and live will become expendable material, this is already a fact where I live. Another fact will be that people will continue to live in cognitive dissonance: on social networks they will talk about "powerful aid packages", "indestructibility" and other national and patriotic appeals, calls to destroy and fight, but in fact, when mobilization affects them, they will try to avoid it. This is also the reality here. In our country, the government cannot provide decent financial support to soldiers who fight for $2,000 a month if you are in a combat position at the very "zero" of the conflict (on the front line in the vanguard) and a paltry $500 if in more remote parts. The average life expectancy of an assault fighter or defender of a position at zero is 16 days. and you are either a half-dead "vegetable" or, if you are lucky, you will be reunited with your relatives "in the other" world. The patriotic part of the war lasts about a year and a half (active) when thousands die per week, then comes pseudo-patriotism, when they "fight from the couches" on social networks, and hide from mobilization, then the stage of manipulation and distortion, when no one wants to fight, in all cities and villages the police, like cattle, catch people to the front, and calls for struggle, destruction and genocide in the event of a front collapse continue on television. Some part of the population left and in fairly safe conditions continues to inflate propaganda, the other part of the population was not affected (women, pensioners) and life continues as it was, and with their answers and activity they distort the real state of affairs and those who are men of mobilization age become worse than slaves. In a highly digitalized society, like in the country where I live, this is death, because they block your card, restrict all services, etc. Ltyshe autonomy saves, but our society is also low in autonomy, so the only way out is death or mutilation through mobilization and war. This will not be stopped by the widespread collapse of infrastructure (now in the capital it is -18 degrees Celsius, there is no heating, light for 22 hours a day and in some places no water supply). In other regions it is a little better, but this is not normal life. This is a collapse, 4 million people live in the capital, this is a complete collapse, but the war goes on and there is no end in sight. There is already a shortage of goods, even bread and drinking water. Total losses (with the wounded, I think already more than 1 million people) 400 thousand people (together with civilians) are considered missing, on the other hand, losses of 3 million. 50% of the country's GDP goes to military efforts, and this is not even the country's money, but loans and agreements on the transfer of minerals and assets. The infrastructure is destroyed, the railway, quite extensive and resistant to war and during, works with great delays and interruptions, there is a critical shortage of weapons, 80% of the income of soldiers is spent on their own means of survival, new ammunition and clothing, transport, fuel and equipment, heating systems. There is terrible corruption and banditry everywhere, even in the highest echelons of power. And the primate people continue to believe and spread propaganda, blind and short-sighted. The BM-21 "Grad" installation is not an old weapon, believe me, it is as deadly as a Mosin rifle or a Thompson machine gun, unfortunately the war has shown that only the mass use of artillery and "human flesh" (infantry) matters. Even without equipment, the war machine will send soldiers with rifles, AK-47s and grenades into the attack if there are generous payments or worthy trophies. The other side shows this, they sign contracts there, because for a monthly (!) payment you can buy an apartment or a house, and for a year you can ensure life until death (If you survive, of course, which is very unlikely :D ). Greed, selfishness and the thirst for money will kill all rationality of survival and well-being in the majority. Drones, drones are an artillery shell that is looking for you to destroy, and drones-shaheeds and missiles are deadly weapons at a distance. ABOUT 120 THOUSAND long-range weapons of destruction (long-range drones and missiles) have already been launched against us, about 10 thousand missiles have been launched over 4 years of war. Read if you want what X101, X-22, the Caliber missile are, what a three-ton aviation guided bomb or thermobaric ammunition is. All these border clashes will seem like a joke, just a warm-up before the real carnage. Imagine the destruction of a cottage with 800 inhabitants in a frost of -15 Celsius, when everything collapsed like September 11 in the USA, and this every week! Sleeping families simply die in the rubble, freezing to death deep in the rear.

So yes, modern war must disappear and the sooner it happens the better, nation-states, empires and other highly organized societies must be broken up into small communities, only then will understanding, humility and restraint come.

Thank you for your interesting post!

As always, brilliantly written and (unfortunately) very very true and wise words.

I pray that you, your family and your land will not be directly affected (or at least not for a while) by the conflicts and that you will be able to live out your dream for as long as possible.

Keep up the good work and stay safe!

All the best from Germany!

-H.