“Democracy dies in darkness”

Common cultural misconceptions and misunderstandings --- [Estimated reading time: 30 min.]

“Democracy Dies in Darkness.”

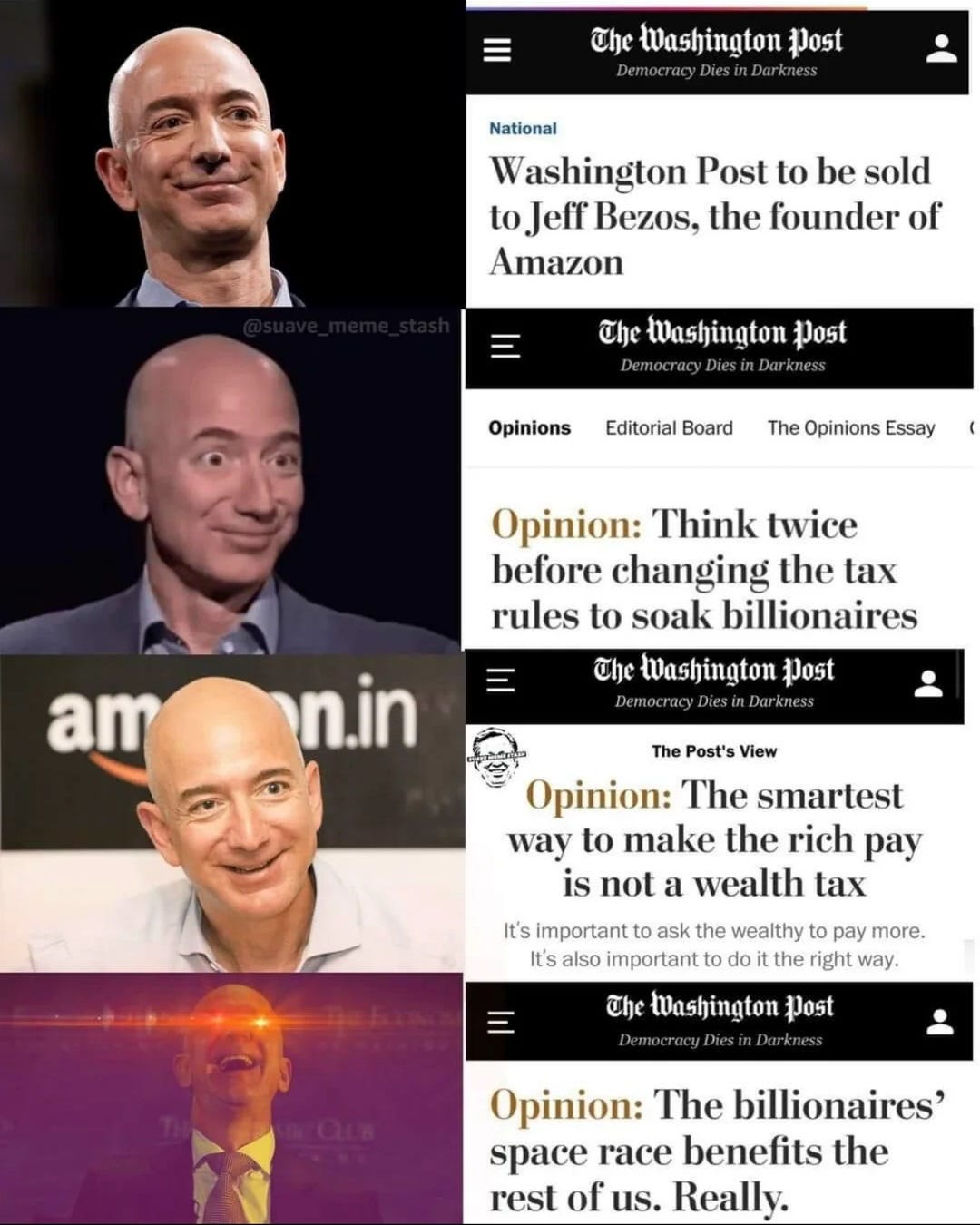

I must admit, it’s a catchy slogan. Dramatic, frightening, and conveying a palpable urgency to keep the lights on and hence democracy alive – all the while leaving most of the implied meaning up to the onlooker’s fantasy. But it inadvertently exposes a lot of unquestioned assumptions and unarticulated beliefs of the dominant culture. The Washington Post has been using the slogan since Trump’s first term, but attributes it to investigative journalist Robert Woodward.

Mind you, this is now the official mantra of the same corporate press rag that once published an opinion piece called “Yes, there is such a thing as too much democracy.”1

Recently, Jeff Bezos (who owns the aforementioned newspaper) ordered the staff to only publish opinion pieces that promote “personal liberties and free markets” as values, since “broad-based opinion section[s] that cover all views” are these days found on the internet. And “the Internet” is now increasingly regulated by “free speech” advocates such as (who would have thought) his brethren Zuck and Musk.

Oh, brave new world.

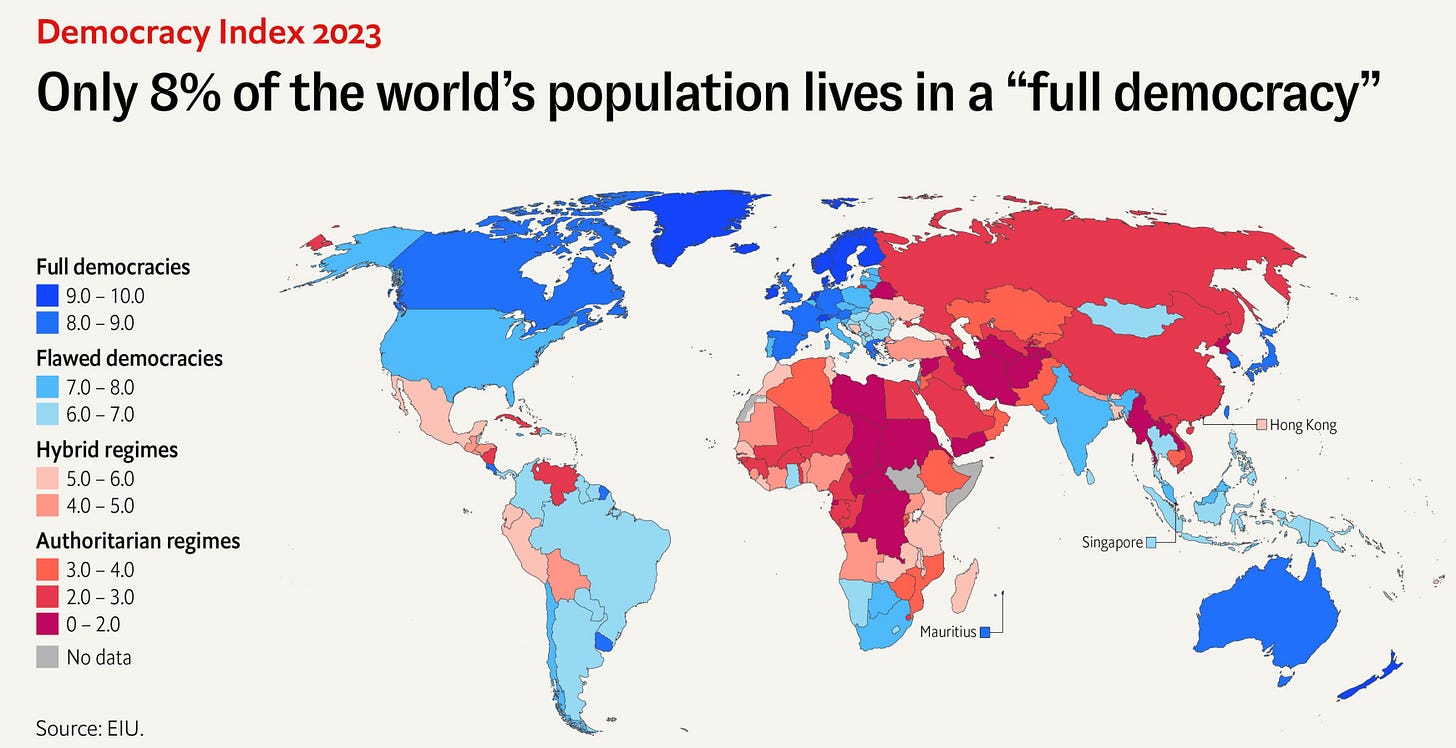

Winston Churchill once famously said that “democracy is the worst form of government, except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.” And he had a point: I’m glad I grew up in Germany and not in China.

Actually, I’m just as glad I didn’t grow up in Thailand either, or in any of the countless other societies in which, from childhood on, questioning authority – or even asking uncomfortable questions – is simply not considered an option. Asking questions is the most natural thing for children to do, and wherever those questions go unheeded (or you’re punished for even asking them) you can expect society to display a certain dysfunctionality, evidenced by an ever-growing disconnect from reality.2

Credit where it’s due, Yuval Noah Harari perhaps put it best:

“Questions you cannot answer are usually far better for you than answers you cannot question.”3

But is democracy the only form of government that allows questions, and are we only now finally free for the first time in human history?

From the time I first started forming my own political opinion onwards I never understood why democracy is supposed to be the gold standard when it comes to human social organization. It has always been pretty dysfunctional in many important respects, especially as it is so obviously flawed even in the countries that pride themselves as being textbook examples. To be clear, I am painfully aware of the irony here: I was questioning democracy, but only because I was being raised in a democratic society that allowed me to question itself.4

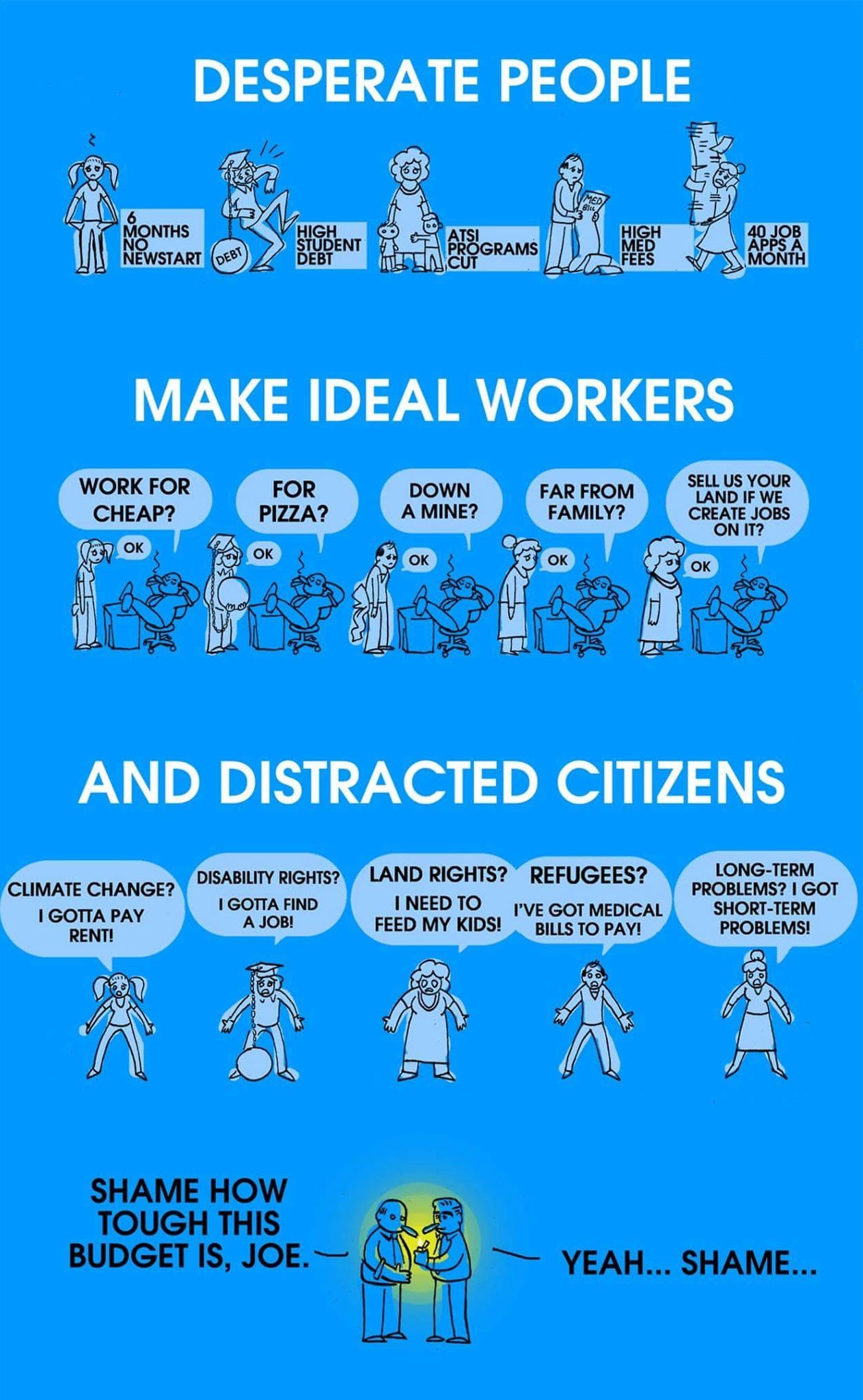

I learned of “revolving doors” between giant corporations and the liberal democracies we were taught to admire. I learned that, even in the world’s “most advanced” nations, “justice” usually meant very little for those with enough money. I read about various “democratic” governments’ efforts to literally control the minds of their citizens, through institutionalized education, advertising, or “public education campaigns.” Most tellingly, democracy completely and utterly failed to reign in neoliberal “free market” capitalism and the concomitant rule of massive, multi-national corporations, often from the shadows.5

And although we might be “freer” than those living in more conspicuously authoritarian arrangements,6 I saw very little real freedom as a member of one of the world’s highest-rated democracies. Everyone just did what Mother Culture (to use Daniel Quinn’s term) commanded them to do, without questioning even the obscenest aspects of it.7

Moreover, it seemed blatantly apparent that very few people were actually living free & democratic lives in the society I was born into. Almost everyone spent the majority of their waking hours executing and following orders and commands, implementing predetermined procedures, and (often ritually) bowing to authority. They had to be at certain places at exact points in time, had to do or say certain things, and if they failed to do any of the aforementioned to the satisfaction of their superiors, they were punished swiftly and severely by cutting off their access to money (i.e. subsistence). People spent most of their time working, and workers are rarely consulted for their opinion and barely have a say in any of the matters at hand. So where was all that “Democracy” that we were told to be so proud of in politics classes?

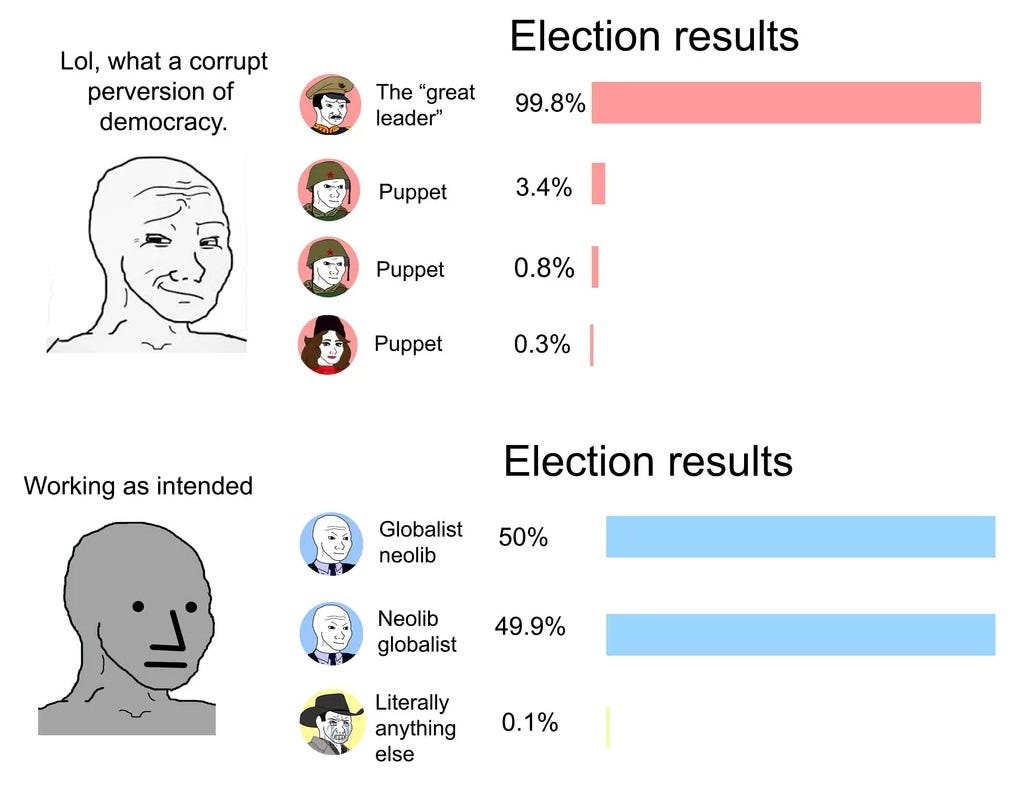

The “highly democratic” Western European society in which I grew up did not seem to change at all, no matter which side won the last election. Things continued pretty much as they always had, and indeed it looked a lot like the most fitting party slogan for all but the most fringe parties was some variation on

“Business As Usual.”

(Terms and Conditions apply.)

In matters of foreign policy, “democracy” usually meant installing a puppet government friendly towards Western economies that sold their countries’ wealth below real value, or otherwise conveyed any number of other economic benefits to the world’s “mature democracies.” The self-proclaimed “World Police” democratized the living bejesus out of every poor country unfortunate enough to be situated on resources (or growing crops) that the dominant democracies required.

As teenagers, trying to be as ‘anti’ as we possibly could, my friends and I – back then staunch communists – used to quip that “democracy is when two wolves and one sheep decide what they’ll have for dinner.” It is, in other terms, the dictatorship of the majority. If only 51 percent vote one way, then woe to the defeated 49 percent!

And when it came to everyday decision-making among me and my friends, voting “democratically” about what to do, where to hang out, which movie to watch or what to eat was often a last resort when no consensus could be reached, and left me with a smug, bully-esque feeling of superiority (when my side won) or a bitter sense of being subjugated (when my side lost).

Ha! Suck it up, loser!

Democracy is often named as one of the major achievements of “Western Civilization” (or, as it was formerly known, the Great White Race). Yet even the earliest version governing Athens during the classical era seems an unlikely favorite of contemporary liberal elites, since well over half of the adult population (women and slaves) weren’t even included in the democratic process.

Until today, democracy continues to not only be presented as the best, but even the final form of government: the ultimate way to organize human societies.

For instance, the political scientist Francis Fukuyama went as far as to argue that history is an “evolutionary process.” According to this creative reinterpretation, the “End of History”8 (to use his words) in terms of human social organization is characterized by “liberal democracy” as the prevailing form of government, since it is “the best.” Oooh-kay.

As everyone with a basic understanding of biology knows, this idea is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of Evolution: despite what the Myth of Progress teaches, the evolutionary process doesn’t strive for a perfect, “final” form, but instead adapts organisms to ever-changing external circumstances. Evolution does not, as such, select for perfection, as much as it does for whatever works well enough in any given environment. There is no end point in Evolution, everything and everyone is subject to constant change.

Just like the Myth of Progress (or other cultural/mythological manifestations of a linear view of time) I view the entire “history-as-evolution” idea rather critically. To me it looks a lot more like history is cyclical, and that after periods of relative stability things can revert back to something far uglier quite fast. All previous iterations of Civilization had their own “Golden Age,” which they proudly proclaimed was actually the way things were always meant to be. Fast forward a few decades, and such statements are exposed for the cosmic hubris they are.

On a related note, the early Star Wars movies were made at a time where many influential thinkers were convinced that the clash of “communism” vs “capitalism” was the decisive ideological battle of human history, after which the winner would rule the world forever. Fifty years later this notion seems utterly ridiculous. Every time humans think that now, finally, they’ve found the Ultimate Answer, after dark eras of ignorance and superstition, history swiftly proves them wrong.9

What I’m trying to say is that all the obsession with democracy seems a tiny bit too supercilious.

Perhaps those that most vehemently defend democracy have not often had the opportunity to find themselves in the minority on any major issue – democracy is decidedly less fun for those who don’t automatically derive strength from numbers. Furthermore, it is not a given at all that the opinion of the majority is automatically the better choice on any issue.

And it is equally important to consider democracy’s current iteration in its energy-economic context: not long after the first oil wells were drilled democracy started “working,” first and foremost because Western countries externalized slavery to a) machines, and b) poorer countries. If we were to “produce” our own energy, mine our own minerals, manufacture our own merchandise and deal with our own waste, we’d find someone to oppress in the blink of an eye, “democratic” convictions be damned.

Yes, “democracy” (not imperialism and fossil energy!) has been credited for reducing poverty rates in overdeveloped nations,10 but something surprising happens when peoples’ immediate concerns go beyond the next meal or the next harvest. In a society that has left behind such immediate material concerns, one in which almost everyone is materially wealthy (judged by historical standards), what happens is that people suddenly have enough free time on their hands to mull over the minute details of their exact feelings about fringe matters that are of no immediate concern for anyone.

One unanticipated side effect of this so-called “post-materialist shift” is the felt need to force your own worldview, which is of course 100 percent correct, on the other side consisting of ignorant plebs and/or slumbering sheep.

Even further down the road in a post-materialist society people polarize and consequently coagulate into ever smaller subgroups, making common goals or even a shared worldview increasingly difficult.

Larger societies, pretty much by default, splinter and disintegrate into warring factions eventually, and the period of relative political & social stability following WWII is an absolute outlier, enabled much more by a hitherto unseen energy bonanza than any democratic principles. Even in decidedly undemocratic nations, this unprecedented energy abundance has raised the (material) standard of living for all but the most marginalized, for the better or worse. A graph depicting the overall rise in (material) standard of living would run pretty much parallel to one charting energy consumption. The former would simply not be possible without the latter.

If we add the Freudian insights that larger groups of people tend to be impulsive, changeable, irritable, and almost exclusively controlled by the unconscious, a more misanthropic (or realistic?) assessment would be that large democracies are pretty much designed to fail, at least in the longer term.

Usually, the larger the group, the less coherent it becomes over time, the more hierarchical and complex its social organization tend to be, and the less “bright” (for lack of a better word) its individual members are (or have to be). As John Gowdy so aptly summarized it, “complex societies require simple individuals.”11

Tiny, easily replaceable cogs in a vastly complex machine.

At the same time, advances in technology have not led to their promised technotopian cornucopia, but have instead alienated and weakened us, divided us and dumbed us down, thus contributing directly to the demise of democracy.

Democracy works a lot better when people are educated enough to perceive its long-term benefits (namely relative social stability – and, optimally, a cap on inequality – in times of sufficient resource abundance) and when they have a broad enough understanding of our shared reality that they can make informed decisions about it. But since we can’t even seem to agree on whether climate change is a threat or not, whether Israel has the right to exterminate their neighbors or not, or whether the removal of a fetus is akin to the murder of a grown-up person, it seems we’ve missed our window of opportunity.

As the population slowly gets more stupid, less aware of what’s happening around them, and trapped in their own carefully constructed abstractions of reality ignorant people slowly start becoming the majority. And once they rule... Well, look at what’s been happening in US politics lately.12 A proper expression of the current zeitgeist.

Would there have been another way? Would it have been possible to keep people smart enough to not destroy the system they depend on? Perhaps.

Unfortunately (for them), we will never find out.

To be perfectly clear: I don’t even say that democracy doesn’t work – it could (and does) work fabulously well on the scale of a community, a village, or even a small town (where everyone knows everyone else). As the Austrian political scientist Leopold Kohr has argued so convincingly, the very problem is “the cult of bigness.” Almost every system could work well on a small enough scale – with the possible exception of capitalism.13

So what do I think is a better form of governance?

When I argue against democracy, or even when I merely point out some of its shortcomings, most people automatically assume that I must be some sort of fascist. But, as the seasoned reader of this blog knows, I’m pretty much the exact opposite: an anarcho-primitivist.

As a primitivist, I acknowledge that for the vast majority of human history we’ve lived as (semi-)nomadic hunter gatherers, so there was little need for democracy. Decisions were generally made by consensus, and if you happened to disagree strongly enough on any issue, you could always bundle up your belongings and stay with some relatives or friends in another band close-by for some time. Once humans settled down, this ultimate ace of conflict resolution was not a viable option anymore, and hence the need for compromises arose.

And as an anarchist, I believe that groups of people are perfectly capable to govern themselves, based on egalitarian principles, wisdom and foresight, and paying heed to every voice – given that the scale is small enough and the people know and depend on each other.

At the scale of your average nation state, people are simply too diverse (and thus too far removed and alienated from one another) to truly care about each other. The British anthropologist Robin Dunbar proposed a concept that helps to explain this phenomenon: there is a real, cognitive limit to how many stable interpersonal relationships the average human brain can handle, and while the exact number may vary greatly between individuals, a good average estimate is around 150 people – “Dunbar’s number.”

Any society that grows beyond a certain scale will automatically and inevitably lead to “othering,” which is (despite what liberals and “humanists” assert) not a bug to be eliminated, but a feature of human sociality. When society becomes too large for you to know everyone, you will value those in your ingroup more than those outside of it, so “us versus them” dynamics develop pretty much naturally at some point.

Most of us are psychologically incapable to conjure up the same amount of empathy and care we have for our inner social circle for random strangers on the other side of the country (let alone the other side of the planet) that we’ve never met before.

Many liberal thinkers muse that this is where the State (with a total monopoly on violence) comes in, and “helps” us by suppressing those “darker sides” of the human psyche.

In fact, it is often the same people who say things like “democracy is the highest good” who really believe that the State exists purely for its citizens’ benefit. They overlook the overwhelming majority of civilized history, in which the state was – at best – more of a nuisance, “best kept at an arm’s length,” to use James C. Scott’s turn of phrase.14

Yet underneath the shiny “schools, roads & hospitals” façade, the state’s main goals are a) self-preservation and b) expansion of power, control and influence.

“To be governed is to be watched, inspected, spied upon, directed, law-driven, numbered, regulated, enrolled, indoctrinated, preached at, controlled, checked, estimated, valued, censured, commanded, by creatures who have neither the right nor the wisdom nor the virtue to do so. To be governed is to be at every operation, at every transaction noted, registered, counted, taxed, stamped, measured, numbered, assessed, licensed, authorized, admonished, prevented, forbidden, reformed, corrected, punished. It is, under pretext of public utility, and in the name of the general interest, to be placed under contribution, drilled, fleeced, exploited, monopolized, extorted from, squeezed, hoaxed, robbed; then, at the slightest resistance, the first word of complaint, to be repressed, fined, vilified, harassed, hunted down, abused, clubbed, disarmed, bound, choked, imprisoned, judged, condemned, shot, deported, sacrificed, sold, betrayed; and to crown all, mocked, ridiculed, derided, outraged, dishonored. That is government; that is its justice; that is its morality.”

– Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, in “The General Idea of the Revolution in the Nineteenth Century”

Historically, the State wanted to extract part of your hard-earned grain surplus, or some money. Maybe your oldest son had to serve in the army, killing other poor peasants like himself to make some guy in a fancy hat even richer. Or you had to perform corvée (i.e. forced & unpaid labor) for the local lord. The state was a sort of sophisticated meta-parasite, first and foremost, that enabled some small echelon of society to live lives of relative ease, leisure, comfort and luxury – at the expense of everyone else.

Nowadays, none of those main objectives have changed – they’ve just been hidden very well underneath a rosy layer of “benefits and services” by an extremely successful PR campaign that rebranded the State as some sort of benevolent benefactor, a quasi-parental entity that exists solely to assist, nurture and protect us.

But, as I mentioned above, the currently expiring iteration of liberal democracy with all its “benefits and services” only works so “well” because of the (temporary) bonanza of cheap energy and abundant resources, which enabled a larger part of the population to access levels of wealth, comfort and luxury that had previously been reserved for the elites. Now that those resources are slowly running out, this version of democracy will find itself increasingly hard-pressed to deliver the same standard of living for everyone and thus unable to fulfill its basic promises.

As the middle class slowly sinks deeper into the quicksand of crushing poverty beneath, it once again becomes more obvious what the real goals of the state are, and where the vast majority of us find ourselves on the chessboard of society.

Whose will is being enacted right now? What are the actual choices at the voting booth?

Even in the most developed societies, a slide backwards into something more closely resembling feudalism is quite obvious. Those that order stuff, and those that race around congested and polluted city streets to fulfill the order; those that work out, and those that work their asses off; those that screw, and those that get screwed.

More and more of us find ourselves struggling to make ends meet, treading the dark waters below instead of climbing the career ladder.

Throughout the Global South, subsistence farmers, who (according to Vandana Shiva) should be among the freest people in the world, have amassed such mountains of debt that they no longer work for themselves, they work for the banks.

For instance, a staggering 90 percent of Thai farming households are indebted. To borrow money from the Agricultural Bank, you need to hand over the title deeds for your land, and all you get to keep is a copy. At this point the banks practically own your land. You toil to pay the yearly installments in order not to be expelled from the land you once owned. How, I ask, is this any different from serfdom? Because they still get to choose between fifty-eight brands of soda (and a similar number of toothpastes) in the supermarket they now depend on for sustenance? Because they can numb their boredom and loneliness with TikTok and their frustration and pain with cheap liquor?

Oh, brave new world, indeed…

No, as of lately it seems like trouble is brewing, and the public – or, better, the majority – begins to seethe with discontent. The current (widespread) support for whatever it is Elon Musk is doing behind closed doors15 is a symptom of the common people being increasingly fed up. They are tired of being looked down upon by people who push pencils and paper (or buttons on their computer) in some sad, sterile office cubicle, tired of toiling endlessly just to stay alive while the bureaucrats and other office drones enjoy remnant employee benefits that the working class had cut long ago in order to increase corporate profits.

And I definitely understand the dissatisfaction with those “unproductive” parts of the social hierarchy. Society has become too top-heavy, and this does not only include the billionaires (although this is the most outrageous tumor of modern society and has to be removed immediately to ensure our collective survival). It includes, say, the global top 20 percent, to which there is a non-negligible chance that you, dear reader, belong as well. Yes, we’ve become incredibly “productive,” but to administer and manage this giant superorganism huge swathes of the population need to be paid to sit around doing rather pointless things.

I even comprehend the general sentiment behind the horrific violence unleashed against anyone deemed “educated” by the Khmer Rouge. I say this not to be edgy, nor of course to justify any of the horrors the black-clad death squads committed, but simply because in more authoritarian societies (such as most nation states in Southeast Asia), the officials, bureaucrats and managers are (more often than not) a terrible breed of people, the exact kind of psychological mixture you also often find among members of the police force (or the military). People who derive some sort of sadistic satisfaction when they find themselves in a position of power, no matter how irrelevant, and who would score high on the personality traits commonly known as the Dark Triad: narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy.

Potential tyrants are attracted to such positions, so this culture actually reinforces authoritarianism by awarding positions of power to those having the least empathy and competing the most ruthlessly. Many officials here seem to enjoy having a part of your life (or your entire life) in the palm of their hand, to have an arbitrary ability to influence your fate, and they like nothing more than to see you sweating and pleading.

At the same time, their status conveys relative impunity, and their salaries allow them to live lives of relative ease and even luxury. Consequently, they rarely forego an opportunity to rub their superior social standing into the faces of those below them. In Thailand, the traditional greeting – the waai – is an indicator of authoritarianism. The higher the (perceived) status of the person in front of you, the higher you hold your folded palms (and vice versa). Similar gestures exist throughout Southeast Asia, and most often they also convey social standing.

Officials demand greeting and treating them with the utmost respect (and perhaps a little gift or a brown envelope), lest they take extra long with processing your request. Because they can.16

If the anger and frustration against “those that don’t sweat” is bottled up for long enough, some sort of explosive release becomes virtually inevitable – and if that explosion is guided by even worse authoritarians posing nonetheless as harbingers of freedom and equality (such as Pol Pot, or Donald Trump), the outcome might be mass violence, perhaps even genocide.

I truly hope it doesn’t come to that, but from what I’ve come to know about history it seems like there is little reason to be optimistic. Some sort of reduction of the human population is inevitable, but as of yet there is no telling which shape it will ultimately take.17

Reducing the current top-heaviness of society in a fair, responsible and respectful manner (such as a widespread and semi-voluntary refusal to have children, as is currently happening) might buy us a bit of time, perhaps even enough to let declining birth rates do the heavy lifting for us (and thus forestalling more violent means).

But, regardless, spinning tops tend to topple once their spin slows down enough.

So is there some positive spin18 on the issue? Well, for starters, there will be a massive need for small-scale subsistence farmers who produce modest surpluses to share with their neighbors while restoring the local ecology,19 and from what my own experiences have taught me the switch from wage slave doing a non-essential job to rewilding gardener doesn’t have to be too painful of an experience. It’s actually quite nice.

I pray that many of us will be able to jump off before the crash.

In his phenomenal monograph on societal collapse, Joseph Tainter wrote the following:

“What may be a catastrophe to administrators (and later observers) need not be to the bulk of the population. It may only be among those members of a society who have neither the opportunity nor the ability to produce primary food resources that the collapse of administrative hierarchies is a clear disaster. Among those less specialized, severing the ties that link local groups to a regional entity is often attractive. Collapse then is not intrinsically a catastrophe. It is a rational, economizing process that may well benefit much of the population.” [Emphasis mine]

Indeed, if “the food is under lock and key” (to use Daniel Quinn’s term again) and you have no way of obtaining any by yourself, they’ve got you where they want you. Unskilled, alone, and desperate.

My friend Arnold from Fight Like an Animal perhaps summed it up best:

“A people become fundamentally unfree when it is no longer an option to pursue a direct means of subsistence from the world itself. When instead the entire world is already someone else's property, and the only plausible means of survival are to negotiate, in some fashion or another, with those who have already claimed everything before one is even born; to work for them, or beg from them, or become one of them.”

Taking all this into consideration, things do look rather bleak, and many have already concluded that “darker days” are ahead of us. But what exactly does that mean? The seasoned reader of this blog has surely come across James C. Scott’s argument that the so-called “Dark Ages” were mostly “dark” in the sense that later historians imagined the worst (projecting their own inability to live without the system) onto everyone when the state collapsed and record-keeping stopped. Yet it is important to remember that people in traditional societies still had all necessary survival skills, crucial knowledge and functional communities.

And, indeed, historically most common folks might have found themselves decidedly better off without the extractive bureaucratic superstructure breathing down their neck. This has changed in recent decades because of massive advances in modern medicine and unprecedented industrial productivity (both in large part enabled by access to cheap energy), but as access to those perks becomes increasingly restricted for everyone but a privileged few, more and more of us commoners will have to make do without them anyway. And once the last veneer of benevolence fades away, who says “we the people” won’t be better off without centralized state authority? Who can assure us that, once push comes to shove, the top of the pyramid won’t turn against us and try to sacrifice us for their own survival?20

The hardest truth is, as the “Brief History of Oil & Humans” chart above shows, in less than a century there will be billions of humans less – but not because democracy stops working, but because we’ve been in overshoot for too long, and we’ve run out of cheap, easily accessible energy, the rocket fuel that sustained our meteoric rise thus far. This is a predicament, not a problem to be solved. Democracy can’t save us.

More than half of the world’s population subsists on calories directly derived from rapidly depleting fossil fuels, and most people only eat because of unfathomably complex supply chains that will start unraveling soon.

Whichever way we look, the future looks scary. And as a result, many feel like we’re already sliding straight into a new Dark Age. Countless people will die, and so will liberal representative democracy.

So, yes, in a way “democracy dies in darkness.” This observation is correct – but only within the metaphorical framework created by the dominant culture, and only if we’re talking about large-scale liberal representative democracy.

(There will presumably be the exact same amount of daylight once “democracy” is “dead,” of course. And people will most likely continue voting on various scales of social organization in the coming age.)

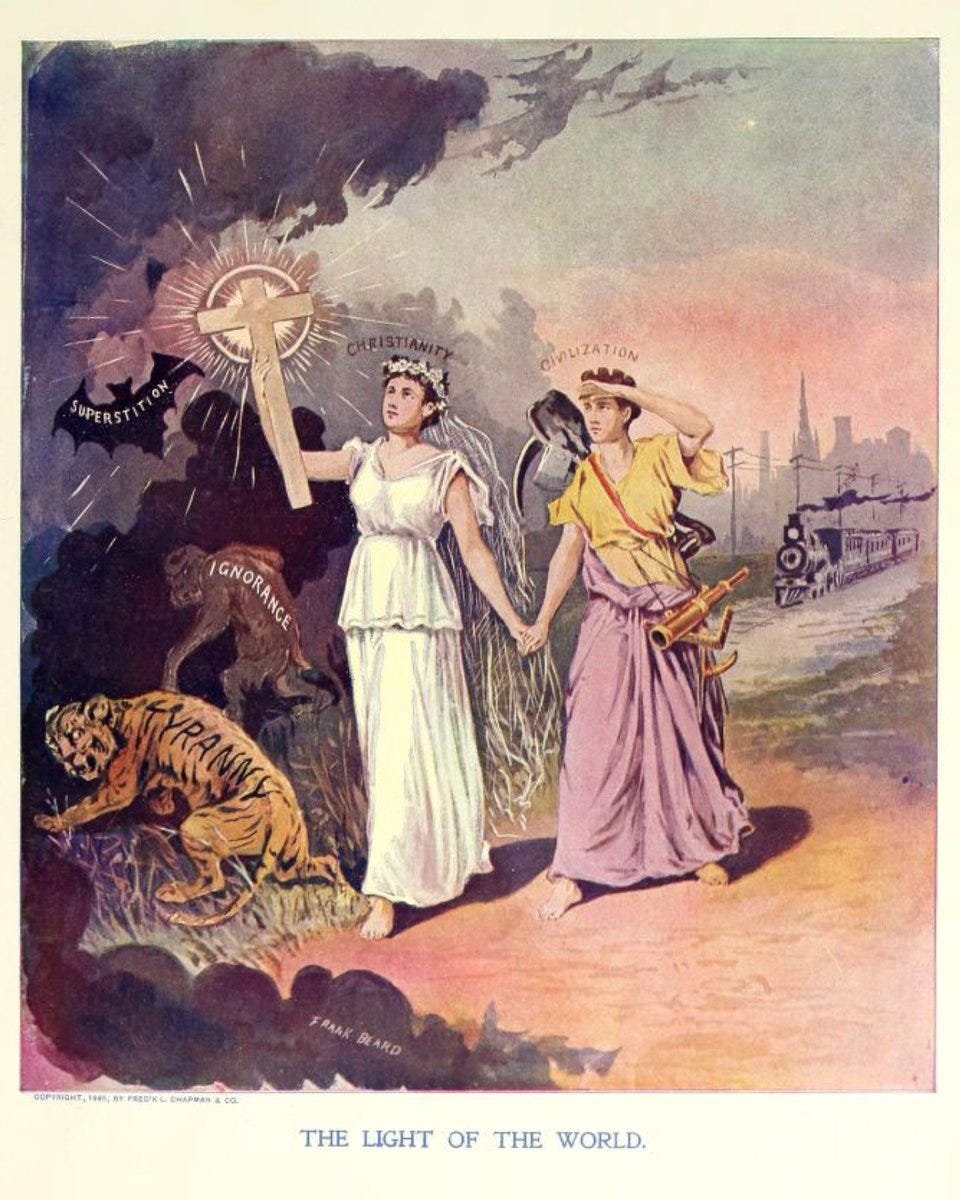

The liberal press has already announced a new Dark Age, which happens because “Enlightenment values” are declining. And here we have it: Light versus Dark, Good versus Evil – the Zoroastrian struggle, a battle as old as Civilization itself.

In this culture’s mythology, there is Darkness, which wages an eternal battle against Light. The first thing the Christian god says after creating the Earth is “let there be light.”

In the binary thinking of civilizations, it is Civilization itself that illuminates the dark, making light a “good” thing, and darkness “bad.” We talk about the En-light-enment as one of the most important and inspiring historical periods, and (especially after the Industrial Revolution) cities literally lit up the night sky. Progress & Development deliver electricity (i.e. “light”) to the rapidly diminishing dark corners of the world, and dark forests are clearcut to let the light in, fulfilling the sacred destiny – and simultaneously sealing the fate – of a culture based on imbalance.

If not the days, then at least the nights ahead will definitely be darker, literally speaking, as governments struggle to keep the lights on. This is already happening in poorer countries around the world. Power supply will increasingly be concentrated around the population centers (cities), leaving much of the outer territories fending for themselves, until electricity becomes intermittent even in the metropolises.

I’m not trying to downplay what’s coming. It will be difficult. It will be tragic. It will be horrific. It is most definitely a scary outlook, and the uncertainty about the future is eating us alive.

It is also inevitable. It is what it is, and there is nothing you and me can do to stop it.

But maybe a bit of darkness is what the world needs. Not “the human world,” mind you (although more darkness would surely benefit our circadian rhythm) – but the World herself. The living biosphere, who is suffering under our pathological urge to literally enlighten every corner of it, whether it’s needed or not. We shouldn’t strive to “eliminate all darkness” (which would have devastating consequences for most other animals), either in the metaphorical or literal sense, but respect the natural balance, and cherish cyclicity. Each and every day, this culture continues to push all other living beings to the fringes, and straight over the edge – a direct result of all our oh-so-enlightened thinking! If we (erroneously) equate the intellect, the rational mind (i.e. the left brain hemisphere) with “light,” then we need its counterpart to avoid an imbalance that will ultimately prove fatal.

The Mbuti, immediate-return hunter-gatherers inhabiting the dense Congolese rainforest, have a ritual song which is used whenever calamity strikes but is only fully sung when someone dies. I haven’t stopped thinking about since I first heard it:

“There is darkness all around us;

but if darkness is, and the darkness is of the forest,

then the darkness must be good.”

We need darkness, just as much as we need light. All that’s left for us now is to embrace it and learn how to live with it again.

Resistance is futile.

As scary as it might seem, Darkness is not our enemy.

I write stuff like the above in my free time, when I’m not tending the piece of land we’re rewilding here at Feun Foo. As a subsistence farmer by profession I don’t have a regular income, so if you have a few bucks to spare please consider supporting my work with a small donation:

If you want to support our project on a regular basis, you can become a Patron for as little as $1 per month - cheaper than a paid subscription!

This was right after Brexit (and right before Trump’s first presidency), when educated liberals discovered that they won’t always be on the side of the majority – due to the Idiocracy effect – and promptly argued for less direct influence on legislative processes by those pesky commoners.

In authoritarian systems (to which I count the largest democracies – my baseline is low) status reports to the next higher level in the hierarchy tend towards the optimistic end, to please the superiors and avoid potential blame or punishment for shortcomings. Right before the collapse, the central authority (the “ruling class”) is thus the furthest away from realizing how precariously close they are to the gaping abyss.

I shamelessly stole this quote from Chusana Prasertkul’s essay “What Crisis?” (I didn’t even read 21 Lessons), which got me thinking about democracy, and consequently prompted me to share my (not uncontroversial) views on the issue of democracy. The full quote by Harari is:

“Modern history has demonstrated that a society of courageous people willing to admit ignorance and raise difficult questions is usually not just more prosperous but also more peaceful than societies in which everyone must unquestioningly accept a single answer. People afraid of losing their truth tend to be more violent than people who are used to looking at the world from several different viewpoints. Questions you cannot answer are usually far better for you than answers you cannot question.”

And right now it seems like the very ability to question everything might be accelerating the system’s undoing. Is climate change a threat? Did the Holocaust happen? And is the Earth actually round?

In fact, more and more people are finally becoming aware that we are already living in an oligarchy (and have been for quite some time).

This statement obviously depends a lot on the definition of the term “freedom.”

Like being able to see your significant other (and children) for only a few hours per day, entrusting your kids to complete strangers for most of the time, working five days and having only two days off, having to drive everywhere, the ubiquity of single-use items and planned obsolescence, money as a measure of a person’s worth or value, etc.

This is part of the title of his most famous book, “The End of History and the Last Man” (1992) – whose main arguments didn’t age particularly well.

A different example comes from the field of medicine: Doctors in the Middle Age were convinced that they knew all the basics of their field, and that while some minor details would perhaps emerge, overall they had gained sufficient understanding of the issues at hand. Modern doctors hold the exact same conviction. Equally, I view the contemporary confidence of modern medicine as overly zealous. For instance, the terrain theory of disease might one day celebrate a comeback – not to debunk and replace the germ theory, but to amend and complete it.

A very shoddy standard, as the switch from traditional subsistence foraging and/or farming to wage slavery is seen as an improvement when judged by this metric. Yes, autonomy, self-determination and personal freedom are greatly diminished, mental well-being and general health deteriorate – but at least people have a little bit more money than they used to. Progress!

Or in European politics. Or in Southeast Asian politics. The US is just the most apparent (and perhaps most extreme) example. But, as surprising as that may seem, by local (SEAsian) standards Trump still has a little leftover margin in terms of ignorance, incompetence, denial of reality and general stupidity – you won’t believe what some of the politicians say around here. The main difference is that (apart from a few outliers like Duterte & Prayut) the messages are being delivered more “politely,” and SEAsian leaders have a lot less global power (and hence attention).

If the exploiter lives next door to the exploited, chances are high that his fate catches up with him eventually.

At worst, the state was a ruthless, megalomaniac project aimed at maximum exploitation and oppression, enabled by widespread terror and bolstered by unfathomable cruelty and violence.

Make no mistake: I don’t think that “making the government more efficient” is actually what Musk is doing (he’s helping his own companies) or that it should be one person tasked with this job (and especially not a mentally unstable ultra-rich man-child), or that this process should happen behind closed doors. (I’m also sure it can’t last for too long, but that would be a whole other discussion.)

All this is verified by my own personal experiences with “la migra” and other branches of the Thai bureaucracy.

Obviously, there will be substantial differences among the various human societies. Different cultures in different locations (and thus environmental conditions) will have different ranges of possible responses.

No pun intended.

As Daniel Zetah from New Story Farm puts it, the aim should be to “produce food as a byproduct of ecological restoration.”

The authoritarian, reductionist and myopic response to the Covid pandemic by the elites may be a foretaste of what’s to come once other problems become too prevalent to ignore.

What an amazing essay! Thank you for this. I rarely comment on anything but felt the need here.

This is one of the most concise and open-eyed writings about our current myths and the likely times coming our way I have read so far. I will save this and come back to it regularly to fully internalise (much like Daniel Quinn’s and Tom Murphy’s work - who both shook my worldview and sent me on a new path I’m still in the early stages of discovery).

I do not yet know what my purpose is in this life, but thanks to writers with profound wisdom like you and many others (Daniel Firth Griffith and Robin Wall Kimmerer come to mind immediately) I can start asking the land what it needs of me and trying to listen for an answer. I know it will take a long time for me to decolonise my mind and be able to hear any answer, but I feel I have overcome the biggest hurdle: recognition that the land, the community of life, our great Mother Earth have spirit, awareness and agency, which we all are part of ❤️🌳🌏🙌

Excellent piece, David. Thank you.