Another day, another dead elephant…

A report from the frontlines of the human supremacist war against Nature --- [Estimated reading time: 30 min.]

Sometimes I really, really hate people. Not humans as a species, I have to add, merely people of the dominant culture. Human supremacists. There are days where I would like nothing more than to shoot lightning bolts from the sky like Zeus, and today is one of those days. This is An Animist’s Ramblings, so ramble I shall.

I don’t know what else to do with my disgust and resentment on these days.

Last night,1 another young elephant bull was murdered by a fruit farmer, electrocuted by a 220V-wire strung around a durian orchard. This is a fairly regular occurrence where we live, yet each time the news hit us like a punch to the gut.

The murderer, the owner of an 80-rai (13 hectares!) fruit orchard, is by no means a poor peasant trying to make ends meet. People with that much land are easily millionaires here, and they most certainly lack nothing in material terms. They can send their kids to good schools, drive the latest Ford Ranger model, and eat pork every single day of their lives. ‘The good life’, you know? But somehow, they can’t let an elephant eat a few durians from their orchard, or break a few branches while they walk through it. It’s their land.

On December 21, 2021, just a few months earlier, Dor Daeng, the young bull who used to visit our garden several times a year, was killed in exactly the same manner – by a durian farmer who didn’t and probably couldn’t accept that elephants have a right to roam as well. Words can’t describe how angry I was (and still am when I think about it).

Although elephants usually roam during the day, they are more often nocturnal these days – forced to hide in the shadow of the night by countless violent encounters with farmers. When they venture into the orchards, they preferably do so around full moon, which allows them to see a bit more. For animals of their size they can be incredibly stealthy, even when walking through the forest. Because the previous owner lived down in the valley and the garden was therefore quiet at night, our piece of land was previously known to the villagers as ทางช้างลง, “the place where the elephants descend” – their preferred path down into the valley.

Dor Daeng walked so quietly and carefully through our garden that sometimes we didn’t even wake up when he came. We found elephant dung along our footpaths the following morning, that’s how we knew. One time we woke up to the (rather terrifying) sound of him eating a stalk of sugar cane maybe five meters away from our house, but when he heard us rustling around in the house he quickly continued walking to the very top of our garden and off into the forest. In the morning we assessed the damage: three banana trees at the border of our garden, the sugar cane stalk next to the house, and a wild fishtail palm in the upper half of the garden. Zero Baht.

On his way through our (pretty densely planted) garden, he somehow managed not to break a single branch, nor did he trample any young fruit trees (the only thing he stepped on was a young tomato plant and a few mung beans which he probably mistook for groundcover vegetation). He squeezed himself up the narrow steps that lead along the chicken fence, damaging neither fence nor fruit trees on the other side.

The time before that, he ate a few wild banana trunks that grow along the border of the land, and again traversed the entire length of our garden, from bottom to top, without doing any damage (except from flattening a single chili plant), carefully following our footpaths.

It’s like he knew exactly which trees we planted and which grew wild, which ones we cared about and which ones we planted with the explicit intention of being elephant food: our main strategy to protect our fruit trees from elephant damage – but more on that later.

Dor Daeng (meaning literally “red penis”, a rather indecent name given to him by the Forest Rangers) was known to the few locals who still hold elephants in high regard as a friendly but shy individual, never looking for trouble, who knew the paths through the orchards well, and who responded to someone calling his name by stopping in his tracks and slowly turning his head in the direction from whence he was called.

Yet someone killed him in cold blood, simply for doing what all animals must do: eating to stay alive.

And those are just the two most recent examples. When we moved here four years ago, our neighbor told us that, just a few weeks back, a whole herd of elephants was killed after eating pineapples injected with the (now illegal) herbicide Paraquat. Last year, a young elephant calf was fatally wounded by several lead projectiles from a homemade muzzle-loading rifle, fired by a fruit farmer. She stumbled into a shallow pond, from which she didn’t have the strength to escape.

It took her three days to die.

That’s how far modern people are willing to go to “protect” what they consider theirs. That’s what farmers are willing to do to avoid even the slightest reduction of “their” harvest. Tell me again, Mr. Vegan, how fruit is supposedly “cruelty-free food”.

But who started it? By far most damage done by elephants is the direct result of a provocation by farmers or, in the broader context, the drastic reduction of habitat caused by the agriculturalist expansion (and concomitant intrusion into wild spaces) of the last century. Some accidental damage might occur here and there, but usually elephants are very careful when venturing into “human territory” – the previous owner told us that an adult elephant once carefully stepped over a stack of roof tiles while walking around the corner of what is now our house in order not to damage them.

If elephants destroy things, it is often done out of anger or frustration. Our place used to be connected to the electrical grid before we moved here: the last owner of our garden had the power line extended over a distance of about one kilometer, from the last “official” pole owned by the Provincial Electricity Authority (PEA) right to our house. A few years back, the owner of another orchard along the dirt road leading to our garden heard an elephant walking down the road and ripping branches off a few betel nut palms. The farmer fired his rifle into the air several times, which frightened and angered the elephant, who – as a reaction – went berserk, ripping the power cord in two, tackling a few of the cement poles it was attached to and snapping half a dozen betel nut palm trunks in half. If the farmer had just left him alone, none of this would have happened.

Elephants don’t actively seek confrontations; they just want to eat. It is not their fault that this most basic activity of all life got a lot harder for them over the decades.

Each elephant needs an area of at least 100 square kilometers to ensure sufficient food, and they forage over a six-square-kilometer area each day. Elephants are nomadic, always on the move, and they eat whatever they find along the way. If they walk through fruit orchards, they usually never stop until they reach the forest again, where they rest and sleep. Elephants need plenty of food – adults eat up to 150 kilogram of vegetation per day – and they preferably eat wild banana trees (mostly the so-called pseudostem, not the fruit), the starchy hearts of coconut, fishtail and betel nut palms, sugar cane, Napier or other fodder grasses, and pineapple plants, as well as all kinds of fruit, bamboo shoots and a large variety of leaves, roots and tree bark. Fruits actually make up a rather small part of their diet, despite claims to the contrary by fruit farmers (a farmer in our village alleged that one elephant ate or otherwise damaged over four hundred durians in his orchard in a single night, a blatant exaggeration that even his fellow villagers didn’t believe).

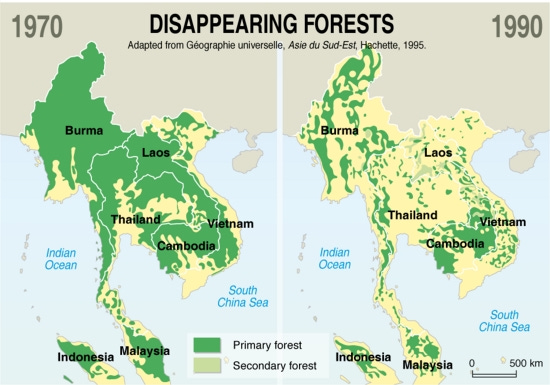

Elephants do descend into the valley more than they used to (and additionally get noticed more often as hedges and borders between orchards are clear-cut, roads are widened, and humans build more and more houses into previously unsettled agricultural land), and even the villagers who are more elephant-friendly say that their behavior has changed over the years. Of course they do, and of course it has. Ever since the dawn of agriculture in Southeast Asia 4,000 years ago, elephant habitat has decreased exponentially, and after half a century of rapid industrialization there are almost no undisturbed places left for them.

Numbers on deforestation in Thailand are often contradictory, with government institutions claiming that the forest cover increased in recent years (quite likely due to a broader definition of what constitutes a forest, including commercial tree plantations and fallow land), even though satellite imaging shows the opposite. According to one source, between 1945 and 1975, forest cover in Thailand declined from 61% to 34% of the country’s land area. Another estimate states that in 1961, forests still covered over 270,000 km², but by 2011, this area was reduced to a mere 170,000 km². The trend is obvious.

Land that used to feed elephants (and the countless other inhabitants of the forest, including aboriginal humans) is now used to feed exclusively one group of a single species: modern humans.

And it gets worse: because most farmers are concerned that any potential elephant food might attract them, they eradicate every plant known to be palatable for elephants. Fishtail palms are chopped down, fodder grasses uprooted, and whole clusters of wild bananas are doused in herbicides, leaving a sad heap of yellowed leaves on a slimy mush of brown biomass infused with deadly poisons. Crops known to be liked by elephants are simply not grown at all: no coconuts, no pineapples, no sugar cane, no jackfruit or breadfruit are found in the surrounding orchards. Only highly domesticated cultivars of bananas are planted – if at all – since elephants favor the wild ones.

If the elephants have nothing else to eat, what exactly do people expect them to do? Dry fasting?

Despite fruit season being the time of the year we look forward to – more fruit than we could ever eat! – we simultaneously dread this period, since people get exceptionally paranoid if their fruit harvest approaches.

People light firecrackers at night that sound like an artillery salvo, and they burn piles of car tires along the border of the Nature Reserve to deter elephants. Some of them keep battery-powered loudspeakers at the edge of their gardens that blare the shrill sound of police sirens all night long.

As the durian harvest drew closer last year, our neighbor, whose father openly brags about having shot monkeys by the dozen on the past (“just for fun”), left his 5-HP generator running for nights on end, to power a wire strung around the entirety of his 3-ha orchard, with light bulbs attached to it every five meters. The whole place was lit up like a country fair.

In addition to this, there is a “vigilante elephant patrol” consisting of village drunks who ride around on their dirt bikes at night, violently revving the engines and tossing firecrackers around. Needless to say, nobody sleeps much.

Especially the firecrackers are maddening. Elephants actually don’t mind a bit of light while foraging (and, contrary to popular belief, light does absolutely nothing to deter them – our own experiences verify this), but for beings who can hear sounds over several kilometers distance due to their exceptionally large ears, a bang like that must be deafening and profoundly agitating. Much louder than a gunshot, the echo of each firecracker rings through the valleys, jumping back and forth between the hills below. They catch you by surprise each time, and each time your heart stops for a second. I believe people with combat-induced PTSD couldn’t spend a single night here during durian season.

But the thing is, none of those approaches work! Every year, elephants descend upon the orchards and eat their fill. No matter how many firecrackers they light, how bright they illuminate their gardens (and how much gasoline they use for this purpose), or how many tires they burn, each year the elephants come again. During our first year here, Dor Daeng walked straight through our neighbors’ orchard, passing his house at a distance of maybe 40 meters, while an oblivious group of villagers was partying and listening to loud music right at his house in the middle of the land (a local tradition we have termed กินเหล้ากันช้าง: “boozing to scare away the elephants”). If one of them wouldn’t have seen the torn banana trunks on his way home, they wouldn’t even have realized that the elephant was here – Dor Daeng disappeared back into the forest as quickly and quietly as he came. The men, suddenly nervous and frightened, lit firecrackers all night long, even though Dor Daeng was long gone.

This shows beyond doubt that their methods of deterring elephants simply don’t work. Yet they continue, year after year, each year seemingly becoming crazier than the last. They are stuck in the vicious cycle described so adequately by Daniel Quinn: they follow a certain strategy trying to solve a problem, but each continuous year they fail to solve it. Each time, their conclusion is that it must not have been enough, so the next year they try more of the same approach that already didn’t work the year before. “Still not enough,” they say to themselves when – alas! – their strategy turns out to be unsuccessful again.

In fact, the way out of the cycle is radically simple: just try something else!

Instead of eradicating any additional food for elephants, plant more of it along the roads! Plant border walls made of elephant food around your gardens, and they are certain to leave your fruit trees alone most of the time! It’s only if they find nothing else that they venture deeper into the plantations, often seemingly breaking branches and trampling smaller trees deliberately, out of frustration over the greed of modern humans!

And even if they pluck a few durians – there are hundreds of acres of durian trees, so why get mad if an elephant wants to try some?

Let me clarify: I don’t want to demonize the locals. We have good friends in the village who respect elephants and don’t participate in the conflict. I write this simply to shine a light on the matter, and I definitely don't intend to look down on people of another nationality, race or creed. Ideologically speaking, the farmers here are the same as most commercial farmers in the world today, including those in the country I was born in: they only think in terms of money and profit, and all living beings that don’t contribute to their profit shall be wiped out or driven off “their” land. If there were elephants in Germany, I’m sure there would be no shortage of people calling for their outright extermination. In fact, this exact discussion is going on right now in regards to wolves who recently started inhabiting parts of Germany again. People can’t seem to accept that there are “animals” in the world that might pose a danger to humans or their possessions.

And it’s the same everywhere. Brazilian soy bean farmer Argino Bedin, quoted in the (highly recommended) documentary System Error (2018), bluntly stated that, before the government opened up large swathes of rainforest for cattle ranching and agriculture, “there was practically nothing in this area when we came here”. Nothing. Oh, apart from one of the most diverse biotic communities on the entire planet, of course. But since he can’t make a profit off it, to him the rainforest is simply “nothing”.

“Animals,” he says, shaking his head, while he drives along one of his seemingly endless soy bean fields and sees three tiny monkeys running out of the field, “they eat all of our crops”. His crops. All of them.

But even here, there are still people who have respect for elephants, even though they are a dwindling minority consisting mostly of elderly folk. There are many remarkable stories about elephants being told by the older villagers, some of which have a myth-like character and attribute spiritual significance to the gentle giants of the forest. One story (as far as we could verify a real one, being told in the same way by various unrelated people), involving a man from the other side of the village, tells how he placed wooden boards pierced with long nails around his garden as elephant traps and ended up stepping into one of them himself while drunk, and – believe it or not – he consequently died of tetanus, a direct result of his (ultimately self-inflicted) injury.

An old women told us about a banana plantation they laboriously hacked deeper into the jungle a few decades ago (before the land became a Nature Reserve); we asked her husband for the story on a different occasion, and he told us the same thing: one morning, on the day when they wanted to harvest the first round of bananas, they arrived at the garden, only to find it ravaged by a small group of elephants. Upon closer inspection, however, they realized that almost all bunches of bananas were untouched, and had in fact been carefully placed on the ground, often right next to the footpaths. Elephants prefer the fibrous trunk of the banana plant over the fruit itself, and apparently the elephants had sensed that people depend on the fruit for subsistence, so they went to great lengths to ensure that any damage to the humans’ crops was minimized.

Let this sink in.

The moral of those stories is great, but they regrettably don’t hold any significance for most farmers today, especially the younger generations for whom money is the only thing that counts. Increase profits by all means. Spray and fertilize until the soil is like one giant adobe brick, baked hard in the sun, devoid of any life. Farm as if there is no tomorrow. Globalization successfully uprooted any connection to the land that their parents or grandparents still held, and the blind implementation of the Myth of Progress, the capitalist creed, squeezes the land dry. More money, by any means necessary.

If people see their land as a goldmine where wealth just waits to be extracted, they’ll treat it one way. But if they see it, like we do, as a multi-dimensional community composed of thousands of different species, all interdependent, sentient, self-aware, and symbiotically interacting with each other for the overall benefit of Life, they’d treat their gardens (and, by extension, the rest of the living world) in a very different way. But it seems people are stuck with the former way of perceiving the world. For now, and as long as the dominant culture holds people in its firm grasp, this won’t change.

The catch-22 here is that 1) people won't change their ways until you prove that they can make money with the alternative techniques you present, and 2) since making money is still the underlying motivation, no substantial and profound change is going to happen in their parasitic relationship with the environment. If your underlying motivation is first and foremost to increase profits, you simply can’t enter a healthy, sustainable and reciprocal relationship with the land – those two things are diametrically opposed.

Aldo Leopold said that “one of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds.” Alone, since no one else seems to realize that the world we inhabit is wounded, quite likely fatally. Nobody here seems too worried about the number of elephants killed each year, or how many are still remaining. People say, well, there’s plenty of elephants in the National Park, and that’s where they belong. Elephants being killed by fruit farmers or in traffic accidents is something that just happens every now and then, but there is no concern among the local human population – often quite the opposite, actually, as I’ll elaborate on in a minute.

It’s difficult to find actual numbers on killed elephants, since many elephant deaths are reported by local media outlets only, and some might never be reported at all (like when a poisoned elephant escapes into the forest and dies there). One source estimates that the number of wild elephants murdered in the six years between 2012 and 2018 is “at least 25,” and the same estimate puts human deaths caused by elephants at 45 or more. Most of those deaths occurred while people tried to chase elephants away.

For comparison, every year over 20,000 people die in traffic accidents in Thailand. Yet each death caused by an elephant makes headlines nationwide, while traffic accidents are so common that only the most gruesome get any media attention at all.

I myself have witnessed two deaths caused by elephants in the eight years I live here, one directly and one indirectly, one justified and the other one mysterious. The first one was a logger who got trampled by an elephant right next to the fruit orchard I used to tend at the border of Khao Phanom Bencha National Park in Southern Thailand. The three domesticated elephants residing there were ‘trained to let tourists ride them’ (read: underwent torture and punishment), and were occasionally used in small-scale logging operations. In one such operation, while dragging a large log up a steep hillside that was simply too heavy for the elephant, he suddenly decided that enough is enough and crushed the logger who goaded him on with his foot, tearing his body in half just above the waist. After hearing about three dozen motorbikes, two ambulances and a police truck speeding along the usually sparsely trafficked dirt road, I decided to investigate what caused the fuss. I have to admit that I drove home with a smile on my face that day.

The second incident occurred shortly after we moved to Chanthaburi. The victim was a young man called Phee Oh, an avid hunter, woodsman and former cardamom farmer, and a recent acquaintance of ours who taught us how to lay traps for small game when he visited our farm. His death still puzzles us, since he knew the forest well and wouldn’t provoke elephants. He went hunting one night, as so often, but this time he didn’t come back. Right before his death, he called his wife and told her that he’d come home sooner because there was an elephant herd in the area, and that she could already start cooking rice. But he never made it out of the forest: his family found his body the next day. He is survived by his wife and their two-year-old son.

Viewed in isolation, every death is a tragedy, whether the victim is an elephant or a human. It’s important to remember that each time a grieving family is left behind – elephant or human – and a life is extinguished prematurely. I don’t wish to downplay all human deaths caused by elephants, and I hope the examples above prove that this is not merely a misanthropic rant, but that I am well aware that things aren’t always black and white.

Yet I think it is equally important to put things into perspective.

Two years ago, we were visited by a Thai woman and a Canadian, Praphaiphat and David, representing Bring the Elephant Home, an NGO that seeks to resolve human-elephant conflict. They had just started planning a project in Prachuap Khiri Khan Province, an area with especially intense conflict (elephants stomped cars and ripped out washing machines from under the houses – imagine what the humans did to provoke such reactions!), which aimed to replace crops that elephants eat (pineapples) with crops they don’t (lemongrass, chili, galangal, etc.). Their project seems to work fine (at least for the humans), and overall conflict has decreased drastically in the time since. Although we would actually prefer an approach that includes elephants – not expels them to the forest – it shows that there are people trying to work out solutions. It’s just that this particular solution can’t be implemented or scaled up in a province like Chanthaburi, which produces almost exclusively fruit. The market demands only so much lemongrass, and the infrastructure for large-scale durian cultivation for Chinese markets is already in place.

During their visit, David told us that elephants kill on average 12 people per year, and, after waiting (unsuccessfully) for a shocked reaction from us, he added “That’s a lot!”

“Compared to what, eight billion?” I retorted.

According to one estimate, there used to be at least 100,000 wild elephants in Thailand in the year 1900. A little over a century later, only two to three thousand are left. That’s at least a 97 percent reduction over the time span of three elephant generations. If that’s not a genocide I don’t know what is.

The remaining elephant population is traumatized, confused and frightened, and only leaves the safety of the forest occasionally, especially during fruit season or when there is not much food found in the forests, such as at the end of dry season. Elephants’ brains are much larger, and if brain size is any indicator of intelligence (it might certainly be a factor, but things are a bit more complicated than that) elephants should be a whole lot smarter than us. We at Feun Foo believe that elephants are, in fact, much more intelligent than modern humans, not least because they don’t have to destroy the world in order to stay alive. They don’t pollute the air they breathe, the water they drink and the food they eat – and there is no action showing a greater lack of intelligence than poisoning your environment.

Elephants are known to be self-aware, empathetic, highly intelligent, emotional, compassionate and communicative beings who have unique individual characters, an impressive capacity for memory and hearing, form complex societies with distinct local cultures and grieve for dead relatives, even holding rituals of mourning for deceased loved ones.

Anyone who is incapable of feeling deep compassion and reverence for those gentle giants is not a functioning member of the ecosystem, and, by extension, must therefore be in a parasitic relationship with it. I have no words to describe what I feel towards those people, and even if I had, I wouldn’t write them down. For now, all I can do is hope that they will perish together with their wasteful and destructive lifestyles once the system they depend on is weakened enough to cause supply chains to collapse and transport to be disrupted. If you pursue an unstable evolutionary strategy, your final destination is inevitably extinction.

One thing we often hear in conversations with locals is a remark on how strange it is that a human who kills an elephant gets punished by the law, but an elephant who tramples a human faces no consequences. While this is often intended as a harmless joke, the deeper implications of this nonsensical comparison are strongly indicative of anti-elephant sentiment. Is an elephant acting in self-defense the same as a fruit farmer merely lusting after a few thousand Baht more net profit? Should elephants be punished if they kill a human? How?

And if you know where to look, you’ll find people openly expressing extremely hateful sentiments towards elephants. In a closed Facebook group composed of locals of the subdistrict we live in, the comment section under the news article about the elephant that I started this article with drew some of the most outrageous human supremacists to voice their resentment. A few examples from the comment section:

“The elephants eat too much. Now they already start eating durian. Don’t worry, soon they'll be extinct.”

“The ones who live in a dream world live far away [criticizing the fruit farmers from a safe distance].”

“I feel bad for the owner of the orchard. He just protected himself and his assets.”

“There are way too many elephants. They come to disturb him and destroy his fruit.”

Profit is the only thing that matters. Humans are the only thing that matters. The dominant culture will not stop until it has devoured the entire living planet.

There have been scattered reconciliation attempts by government officials, often by trying to compensate fruit farmers for losses caused by wild elephants. The last such program asked people to estimate and report their financial losses in Thai Baht to apply for compensation. Unsurprisingly, the majority of farmers in the area suddenly claimed damages in the range of tens of thousands of Baht – utterly untenable amounts of damage to be caused by only a handful of elephants – and the program was immediately abandoned. Greed is the only reason why it didn’t work, and greed is the underlying reason for human-elephant conflict.

But it runs deeper than that.

Elephants remind us that humans are not immune to being killed – even accidentally – by other animals. It scares us that there are beings so much larger and stronger than us, beings who sometimes charge instead of fleeing us, when our culture teaches us that we are the pinnacle of evolution, the apex predators, the conquerors and undisputed rulers of the world.

This might be another reason why people seem to focus rather irrationally on those deaths (as opposed to traffic accidents): people in traffic accidents die either because of other humans or because of the machines they build (that are generally seen as an accomplishment, despite the fact that a strong argument can be made against those machines for being the fossil-fuel-guzzling environmental nightmares they are), leaving the human supremacist worldview intact. Elephants, on the other hand, remind us that we're not the masters of this world, and that there are still enormously powerful beings that can pose a real threat to us. In a way it exposes the myth of human supremacy over the living world for the lie that it is.

We might be the species with the largest capacity for violence, but that feat doesn’t automatically make us superior – especially not in the moral sense. Quite the contrary, the fact that the ecocidal and anthropocentric dominant culture actively encourages this feat, both against fellow humans and the rest of the biotic community we inhabit, is all the more a sign of its inadequacies and its inherent unsustainability.

There is a reason why agriculturalists systematically exterminate all creatures larger (and smaller!) than themselves that they can’t turn into profit and/or that pose even the slightest threat to their surpluses and profits. There used to be elephants in the Fertile Crescent, in Mesopotamia (what's now Iraq, Iran and Syria), the birthplace of agriculture. There used to be forests, too, stands of cedar so thick that the sunlight wouldn’t reach the ground – before the agriculturalists cleared them to bring more land under cultivation.

There used to be wild elephants in China.

The indigenous people of Southeast Asia coexisted with elephants and only hunted and killed them occasionally – elephants are simply not the preferred prey of any foraging people inhabiting their natural range. But it seems like the agricultural lifestyle, on the other hand, is fundamentally incompatible with certain efforts to preserve what’s left of the biosphere.

If people feel entitled to envision themselves as the exclusive and absolute owners of a particular patch of land, its other inhabitants are constantly going to remind them that they have a natural right to live there, too. That’s what all the elephants do. Land ownership is a product of our modern human imagination – and the land fights back.

This land belonged to the elephants long before there were any humans, and it still belongs to them, whether we accept it or not.

For us the answer to this dilemma is obvious: to slowly become a part of the landscape again – not its master, owner, and manager. One species among myriad others, that respects every other species’ intrinsic right to existence. But obviously that’s not what most people these days strive for.

That’s also why conflict is inevitable.

Instead of reducing the amount of elephant food in our garden (impossible, since we really love bananas!), we actively increase it. All foods preferred by elephants are easily propagated and fast-growing. Especially in the topmost part of our hillside garden, we have established what we jokingly refer to as the “elephant buffet”: here we plant all their favorite foods, as densely as possible, to allow them to eat their fill right before or after crossing our garden. Most parts of the border of our land are planted with wild bananas, clusters of fishtail palms and rows of pineapples, and whenever an elephant ventures in our garden at a new spot, we immediately plant those species there as well, so that a nice surprise awaits them when they return.

We believe that our felt intentions can have an influence on other living beings (for instance, the reason why we have ‘a bad feeling’ about someone might be caused by his bad intentions towards us), so while planting crops that elephants eat as well we keep the explicit intention in our hearts that what we are doing right now is planting elephant food, and that we don’t care whether we harvest something from the plant in question or not. The plants will carry this sensation within them, and the elephants can sense it, both from us and from the plants, showing them that this place is inhabited by friends who care for them.

We never light firecrackers or make other loud noises, and turn off all lights at night (to not disturb insects and other nocturnal animals). If we become aware of an elephant in our garden, we keep the lights off, stay inside or under the house, avoid sudden moves or loud noises, and talk to him in a calm voice, telling him that we are happy and honored to see him again, to eat whatever he wants, to be careful with the chicken fence, and that he is safe and always welcome here.

So far, the strategy pays off: the elephants don’t visit our garden any more frequently than before, or any more than the surrounding orchards. Planting more food for elephants doesn’t attract them, it just ensures they can eat and continue their journey.

The elephants seem well aware of who holds friendly attitudes towards them and who doesn’t, they can tell who’s friend and who’s foe: all damage to fruit trees that occurred in the area around our garden since we moved here was in orchards owned by people who light firecrackers and try to drive elephants away.

In the end, whatever we say to our neighbors is bound to fall on deaf ears, since people can always argue that we’ve been lucky so far, because the last time a whole herd of elephants visited this garden was over ten years ago. Horror stories such as the one about the only jackfruit plantation ever planted in the village (which was devastated by elephants some decades back) make people think that this is what the elephants come down into the valley for: to wreak havoc among their orchards, destroy their belongings and reduce their profits.

Nobody thinks that the real mistake in this story might have been to plant dozens of acres of a fruit that all simultaneously ripens at precisely the time when there is not much food available in the forests. And if there is only one crop, what else should the elephants eat?

As a reaction to the hostility towards our hulking herbivore neighbors, we increase our efforts to plant elephant food along the borders of the land we tend – much to the annoyance of our human neighbors – and along the footpaths that wind through it, and we pray that one day the herd comes back and walks through our garden once more. Let them come. Only then can we assess the “damage” with a wide smile on our faces, honored to have been visited by such an impressive delegation of Nature’s awe-inspiring beauty and strength. Only then will we have irrefutable proof of how little damage they did to our garden, a safe space where they are welcomed and revered, and how much to the surrounding monocultures.

Losing a few fruit trees is nothing compared to losing one of the most majestic species that we share this planet with. Trees can be replanted, and all we lose is a bit of time. But once the elephants are gone, they are gone forever.

Update 01/01/2023:

Last year (2022) has been the first year since we moved here (and, according to our neighbors, the first year ever) that not a single elephant traversed our garden. The bull mentioned in the footnote above is around sometimes, but probably too afraid to get closer to people’s homes.

We are witnessing elephants going extinct, right on our doorstep.

Out of anger and frustration, we invented a certificate for “Elephant-friendly Fruit Orchards” - of course we are the only ones holding it - part effort to draw attention to the issue, part provocation. We don’t know what else to do.

Update 04/20/2023:

Confirmed: There is a new elephant bull around! Last night, he traversed the entire length of our garden, again without doing any damage! It might be that he came all the way from Trat (the next province), but he seemed to know the place (maybe he came here as a child once?), since he knew exactly where to walk - following in the footsteps of countless generations of wild elephants whose preferred travel route leads right through our garden. It seems like he might become a regular visitor! Here’s a Facebook post from our page detailing the visit.

Update 05/26/2023:

The young bull decided to stay! He has been around again for the last three nights, and we heard him walk and eat noisily in the forest right behind our land - it was so loud the first night that we were 100 percent certain that he was in the upper part of our garden, but when we checked the next morning there were no signs. So far, he prefers to stay within the safety of the Wildlife Sanctuary, probably carefully studying the humans around to see who’s friend and who’s foe. Good news!

I started this essay a few months back and just got around to giving it the finishing touches. In the months since, luckily no more elephants were killed in our subdistrict, and this year’s durian season was even a bit more quiet than last year – probably because Dor Daeng, the only elephant that used to be a regular visitor in our village, is gone. We miss him and we hope that another young male will soon take his place. Needless to say, we make sure there is enough food for him. And maybe we’re lucky: last month, an unknown young bull came to drink water at the pond of our neighbor, after which he disappeared into the forest again. Let’s hope he comes back!

Excellent piece. Subscribed and sent a small donation.

Thank you David!