In Defense of Delayed-Return Hunter-Gatherers (II. of III.)

Addressing an unmerited bias in Anarcho-Primitivist circles --- Part Two: The Truth About Slash-and-Burn --- [Estimate reading time: 25 min.]

This is the second part of a three-part series on delayed-return hunter-gatherers, based on an interview I did with Artxmis for the Uncivilized Podcast. If you didn’t read the first part yet, click here.

The truth about slash-and-burn

Before we continue examining the relevance of swiddening cultures for anarcho-primitivist theory and thought, I deem it necessary to delve a bit deeper into the details surrounding this highly fascinating subsistence mode that many primitivists are so unfamiliar with. With the following, I also aim to provide a framework to transcend the common “agriculture good vs agriculture bad” discussion we primitivists so often find ourselves in, by showing that “agriculture” is not agriculture (see Part One for the definitions I use).

More often than not, slash-and-burn is grossly mischaracterized by the dominant culture, and one commonly encounters descriptions lacking depth, context, and (frankly) truth, such as in the following description of “hill tribes” from a random website:

“The hill tribe peoples normally live in mountainous forest regions, using slash and burn (swidden) agriculture, migrating to new areas when the soil is depleted.”

This perpetuates the myth of the inherent destructiveness of humans (which I recently elaborated on), and shows very little understanding of the realities of shifting cultivation. While it is true that soil depletion is increasingly becoming an issue wherever hill cultures have been forced to settle down and grow corn for the commodity market in short rotational cycles or even fixed fields (i.e. wherever horticulture becomes agriculture), soil depletion is not what necessitates shifting cultivation and drives migration – ecological succession is. As long as swiddeners are allowed to practice their traditional subsistence mode (with long rotational cycles of at least several decades), soil quality increases over the long term. But wherever hill cultures have been (forcibly) settled down, culturally assimilated and forced to take part in the market economy, the same problems inherent to agriculture become prominent in (what’s left of) traditional systems of plant cultivation.

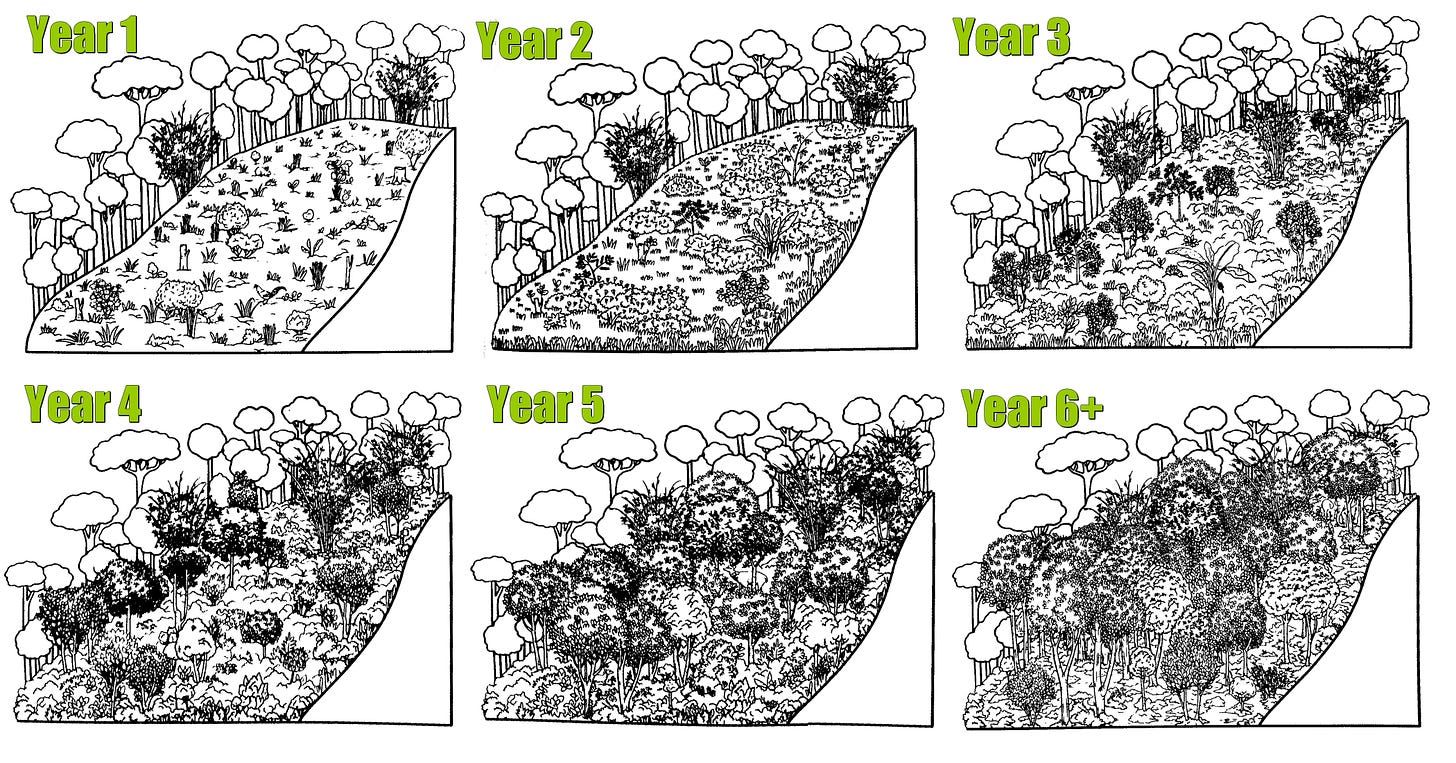

As I pointed out in the interview with Artxmis (and in the previous Part), traditional swiddening is in many respects much closer to foraging than it is to farming. Sure, as swiddener you do some (initially quite drastic) wildtending, similar to many Native American societies that employed fire1 to nudge their ecosystems towards more productivity, and this looks pretty extreme in the earliest stages – clearing a patch of rainforest and burning the vegetation – but once that’s done, you pretty much work with the land, utilizing ecological succession and following the same goal as the land itself has (forest cover with high levels of biodiversity and net productivity).

Among Southeast Asian shifting cultivators, rice is often grown in the first two years in newly cleared swiddens. Botanically speaking, rice – as all other grains – is a grass, an early successional species, and it needs bare soil and plenty of sunlight: just the kind of conditions created by a forest fire. Soon after, various herbs, shrubs and vines will start to establish themselves (or are planted among the rice), and ‘weeds’ (many of which are edible or have medicinal properties) will sprout up everywhere – this is the niche of many of the cultivated crops and vegetables, such as “banana, papaya, eggplant, maize, sugar cane, cucumber, squash, tobacco, taro, cocoyam, sweet potato, millet, Job’s tears, stringbean, wingbean, sesame, ginger, basil, cockscomb, and more” (Tsing, 1993).

A bit later, pioneer tree species (some of which are fruit trees or trees with edible foliage or seeds) will shoot up above the herbaceous layer, and start to overshadow it, thus suppressing the early successional species’ growth. Late successional dominants (such as several fruit and nut trees, as well as other wild trees like dipterocarps that yield valuable forest products such as resin and wild honey) will soon start growing in their shade, attracted by the fertile, cool soil that the pioneers busily prepared for them.

What this means in practice is that, according to guidelines passed down for generations, suitable time frames for the clearing and the burning of the plot in question are chosen. The clearing is mostly done by the men, especially among South American horticulturalists. Prior to the introduction of steel axe heads and machetes, those societies used stone axes2 or direct burning, which made the process much more labor-intensive and thus likely resulted in smaller but ‘wilder’ swiddens with more mature trees that would have been too time-consuming to fell.

After the land is cleared, the vegetation is usually allowed to dry a bit – but not too much, since otherwise only very little charcoal is produced and fires are more likely to burn too intense and too fast, destroying wild fruit trees or other useful plants that might already grow on the plot and have been spared during the initial clearing. Then, fires are laid at strategic points and the dry slash is burned off.

Following this controlled burn, Southeast Asian hill cultures sow rice directly into the ground. A group of men slowly moves uphill with long sticks in their hands, poking holes in the ground as they walk, and the women follow behind them and scatter rice (and other) seeds into the holes. Within a few short days, the rice starts sprouting, and in a matter of weeks, the hillside is completely covered in young, bright green blades of hill rice (a strong, tall variety that doesn’t have to be planted in flooded paddy fields3).

South American delayed-return hunter-gatherers/horticulturalists don’t cultivate grains, but instead focus on starchy tubers like cassava and sweet potatoes. They simply transplant crops and cuttings from their previous gardens into the freshly cleared swidden. Among the Achuar in the Ecuadorian Amazon, for instance, the man of the household plants banana shoots right after the initial clearing, which is usually also the last time a man enters the garden. Afterwards, the garden becomes the responsibility, the domain and the private refuge of the woman, in which childbirth usually takes place and emotions (whose public expression is spurned) can be expressed freely (Descola, 1996). Unlike dull and repetitive agricultural work, gardening is a highly spiritual activity for Achuar women, and they constantly sing and pray to the Nunkui spirit of the gardens and individual plant spirits. The women take great pride in their gardens, and a lush and productive forest orchard conveys high social status.

“With the aid of digging sticks of chonta wood, the women first plant manioc [cassava] cuttings all over their plots, then distribute in apparent disorder yams, sweet potatoes, taroes, beans, squashes, groundnuts and pineapples. All that then remains to be done is to plant the trees whose seasonal fruits help to vary the somewhat monotonous everyday diet: chonta palms, avocado trees, sweetsop trees, ca'imitos, ingas, cocoa trees and guava trees. These tend to be planted along the edge of the area, totally cleared of grass, that surrounds the house, a collective space that is not subject to the exclusive jurisdiction that each wife exercises over her own parcel of land. Here also are the plants that are used communally by one and all: pimento, tobacco, cotton, bushes of Clibadium and Lonchocarpus - the juices of which asphyxiate fish caught with the poison - gourd plants, rocou and genipa for face-painting and, last but not least, herbal remedies and narcotic plants such as Stramonium.

When mature, the garden resembles an orchard set in amongst a vegetable garden standing high with produce. The tall papaya stems rise above a most impressive tangle of plants; the taroes spread like monstrous sheaves of arum lily leaves, the peeling banana trees intertwine and stoop beneath the weight of enormous bunches of fruit, the squashes swell like balloons at the foot of charred stumps, carpets of groundnuts border thickets of sugar cane, arrowroot flourishes along the great fallen tree-trunks left over from the felling operation, and everywhere the bushes of manioc unfurl the tentacles of their finger-like leaves.” (Descola, 1996)

The reason why so many people recoil at hearing “slash-n-burn” is because they imagine it to be what civilization usually does to the forest. Cut roads into it, selectively log the most valuable timber, sell the minor timber trees to locals, pile up the remaining vegetation with bulldozers, wait for months until the remaining biomass is tinder-dry, and set it ablaze to clear the land for cattle ranching. That’s not ‘slash-and-burn,’ that’s ‘bulldoze-and-incinerate.’ A more apt term would be scorched-earth-farming.

It is also important to remember that any swidden will be forest for well over 90 percent of the time people visit it. Clearing and burning takes less than a month, and rice (or other early-successional staples) dominate the landscape for only two years. For the most part, swiddens are more like hyperdiverse fruit orchards that also supply an abundance of useful materials, medicines, honey and other forest products. It might easily be fifty years or longer until somebody clears that patch of land again, and in the meantime any carbon loss from the initial burning is paid back to the land with interest (since some of the original carbon biomass is now stored in the soil as biochar – which, as I say in the interview, was a crucial ingredient in Amazonian dark soils, or terra preta del indio).

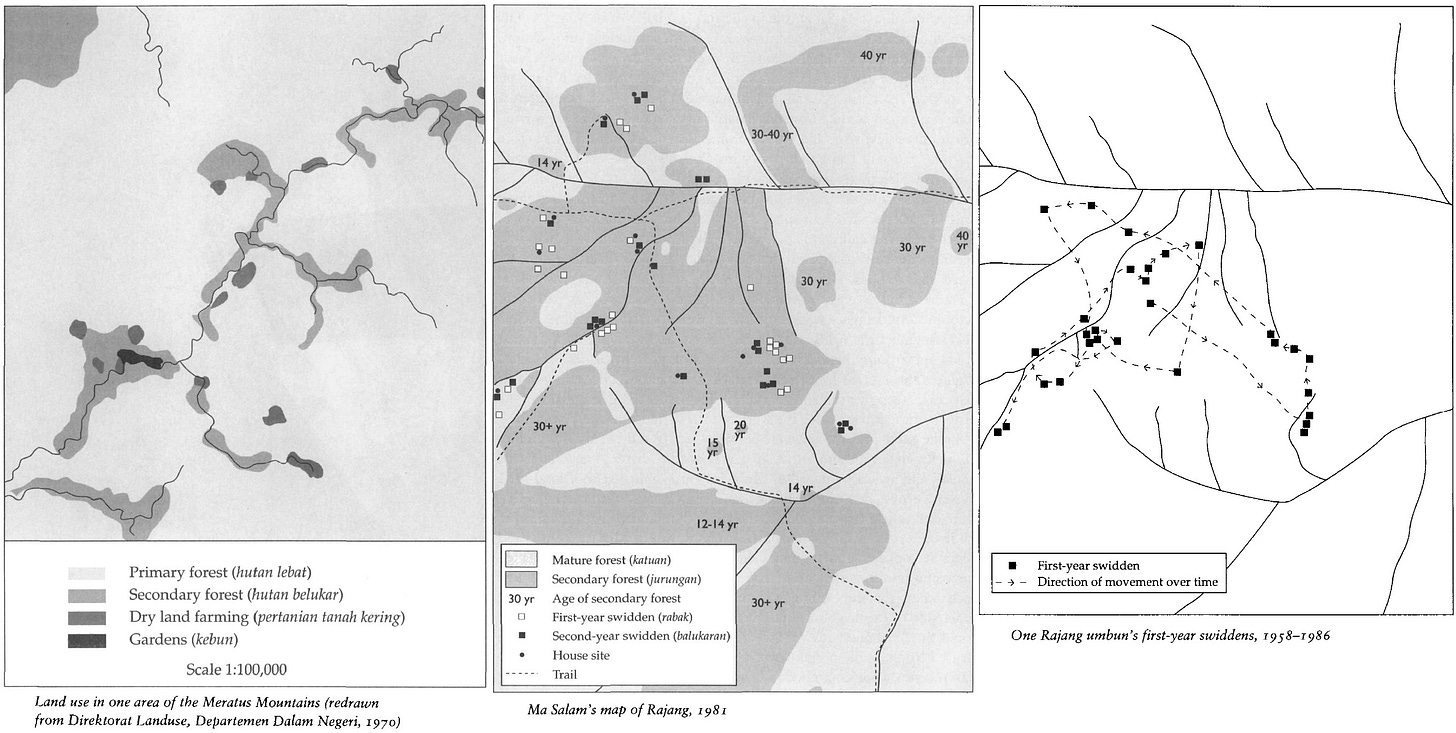

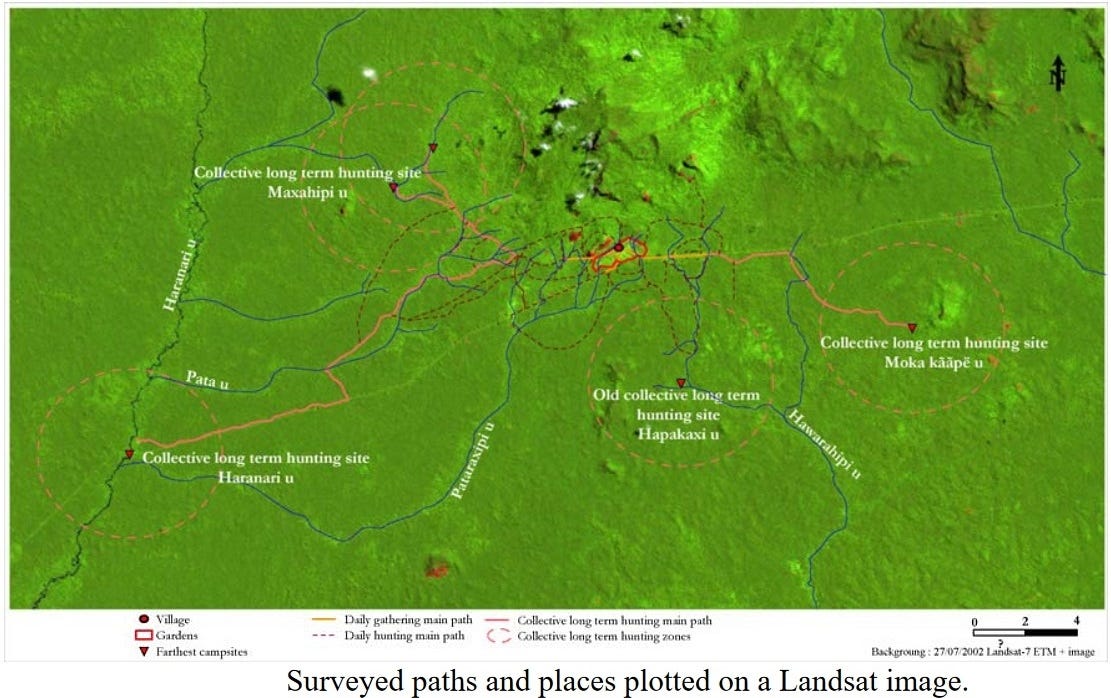

When looking at the bigger picture, it is impossible to overlook the fact that swiddening remains one of the least invasive methods of ‘farming’ there are. To visualize this, let me share a few maps. Three of them are from Anna Tsing’s ethnography:

The other three are from a list of supporting documents for Bruce Albert’s research on Yanomami ethnogeography and resource use:

Swiddens are mostly confined to the vicinity of rivers or streams, and make up a vanishingly small percentage of the whole land area, tiny specks in an endless, dark green ocean. Shifting cultivation seems to impose an upper limit on population density, of about 20 to 30 people per square kilometer (Scott, 2009). As a comparison, Uruk, around 5,000 years ago the largest city in the world, had a population density of between 10,000 and 15,000 people/km2, the most densely populated city in the world, Manila, currently houses over 43,000 people/km2 – whereas hunter-gatherers generally live in densities of about 0.5 to 5 people/km2.

All this is to say: shifting cultivators tread very lightly on the land they inhabit. Concerning both population density and the impact they have on the land, they are much closer to hunter-gatherers than to agricultural societies and the earliest civilizations.

When the first two or three years are over and the household tending the swidden (called umbun among the Meratus Dayak – the exemplary swiddening culture I’ve selected as a case study for this series) moves to a new site, the old swidden is still visited regularly. By then, fruit pits and other seeds that have been scattered, both intentionally and unintentionally – and those that actively planted by the people of the household, of course – have grown into young trees, some of which might have already commenced fruiting. In the following years, the canopy will already be closing in most places, although many perennial crops remain productive and are harvested weekly.

Once five to ten years have passed, the first larger fruit and nut trees will start bearing fruit, and in the understory, many edible crops remain – often propagating themselves. Plants like yams, cardamom, ginger, black pepper, etc. will grow pretty much on their own and with little human attention required. People may now come only once per month, or more often during the season of some of the fruits. The site of their current umbun is now located further away, so most of their staple foods are found closer to home. But as the forest reclaims the land, abundant harvests of nuts and fruit also attract a large variety of wild animals, which are hunted by the men.

In a few short decades, the jungle has grown back to an extent that an untrained eye can barely differentiate it from natural, undisturbed rainforest. And even experts, like professor of tropical ecology Charles M. Peters, can be fooled easily just by how closely those anthropogenic food jungles resemble natural forests. In his 2018 book Managing the Wild, Peters describes how he visited the forest behind an old Dayak man’s house, just to discover that what he took to be a beautiful, relatively undisturbed piece of mixed Dipterocarp forest, was actually a fruit orchard, tended for centuries (if not longer) by the local Dayak community. According to Peters,

“The forest was relatively open, yet multistoried, with numerous palms and climbers. Many of the canopy trees were heavily buttressed and over a meter in diameter.”

When he realized that this was not pristine forest, but a large, naturalized jungle garden, he asked the old man about some of the trees, and was surprised that the man not only knew all trees, but also when they produced fruit and how many baskets they yield, how old the trees were – and the name of the person who had planted each individual tree.

The old Dayak man showed him around that day, and as they walked through about two hectares of wildtended hill forest, Peters was shown

“five species of mango trees, seven species of breadfruit, six species of rambutan, eleven species of rattan, and three beehives. [He] counted forty-six [!!] large durian trees, sixteen sugar palms, and several dozen canopy trees that produce milky latex or other exudates of value. [The] local villagers were managing thirty to forty species of trees and an inestimable number of palms, climbers, shrubs, and herbaceous plants.”

This surely doesn’t sound like a barren landscape only intended to feed humans!

While only the initial clearing of the swidden attracts public attention, no attention whatsoever is paid to what happens in the decades after. People live pretty much like hunter-gatherers, but make their lives easier by carefully tending to their environment and encouraging the growth of some plants over others – all the while producing a steady staple crop of rice with what must be the least labor-intensive method of rice cultivation in the world. Their old swiddens are like a supermarket, a hardware store, a pharmacy and a butcher’s shop all combined, and they can easily satisfy their immediate needs by foraging (i.e. ‘hunting and gathering’) in their current and previous swiddens.

The aspect of shifting cultivation most deserving of our attention is thus not the initial clearing of the land, but what happens in the years after the clearing. In the following decades, fruit trees will continue to produce abundant harvests, the most prized of which is durian. Those trees are planted around the house and into the swidden right after it is cleared, and once the trees are large enough to cast shade over the open area around the houses, families have long since moved to a new swidden. But when durian season begins, the Dayak pack a bag of rice and a few cooking utensils and move back to their former swiddens. Everyone, but especially the children, enjoy this change in scenery and the opportunity to live right in the forest for a while. Once arrived, they build palm-thatched huts (or repair those left over from the previous years’ expeditions) to cook and sleep in during the fruit harvest. The harvest itself couldn’t be easier: durian trees are very tall, but the fruit simply drops when ripe, so the area under the trees is slash-weeded with machetes to make the fallen fruits easier to find.

“This selective weeding, especially around the durian and illipe nut trees, is an important management tool used to maintain tembawang [the forest orchard]. During these weedings, the seedlings and saplings of valuable species will be spared, while unwanted species will be cut. And the decision—cut this one, save that one—occurs spontaneously during the swing of a bush knife.

[…]

The community stays out in the tembawang for the entire durian season, eating and sleeping in the huts, weeding and planting new seedlings, washing plates, cooking rice, and periodically, and always with an upward glance, going out to collect the durian fruits that crash to the ground.The children are usually sent out to collect the fruits, which fall with greater frequency at night, when everyone is in the hut talking, smoking, and eating durian. At the sound of a large thud, the father will glance over at one of his children, who will grab the kerosene lamp and run out to find the fruit.” (Emphasis added; Peters, 2018)

All of the aforementioned should, again, make perfectly clear that life as shifting cultivators is in many crucial aspects much more like foraging than like farming. I, for myself, am not sure I could imagine a more rewarding and wholesome way of life. If I could choose to be born into a certain culture, delayed-return shifting cultivators would definitely be my first choice.

All this stands in stark contrast to (totalitarian) agriculture. Agriculture means imposing ones’ own anthropocentric will onto the land. It creates and reinforces anthropocentrism, since the role of the human changes drastically, and, as Daniel Schmachtenberger has pointed out, “following the plow, Animism died everywhere.”4 It is akin to saying ‘this diverse ecosystem feeds hundreds of species, but I will raze it to the ground and force it to produce only a single crop, intended for me and my family, and no other living being shall eat from it.’ Since agricultural societies usually depend on some variety of grain, and grains are grasses – early successional species – the disturbance to the land has to be repeated each year – the tilling of the land – to reset succession and forcibly create the right ecological niche for grains to grow. It is a never-ending war against Nature.

Shifting cultivation, on the other hand, is based on careful observation of how the ecosystem works, and tries to help natural processes along – or even speed them up a little.

It is akin to saying “Nature seems to benefit from occasional disturbances, so let me attempt to create such a disturbance, using the least effort possible, and afterwards aid the ecosystem in the recovery, while producing food, materials and other necessities for me and my community as a side effect.” The resulting food jungles are some of the most biodiverse ecosystems on the entire planet.

“The Kenyah [another indigenous swiddening people in Malaysia] are simultaneously managing [sic] 125 tree species per hectare in a forest orchard— an unprecedented feat of silvicultural prowess. […] In my opinion, based on what I have seen, studied, and measured over the past thirty years, these villagers are the most gifted foresters in the world.” (Emphasis added; Peters, 2018)

Horticultural societies have existed since beginning of the Holocene, when a stabilizing climate allowed for sedentarism and hence plant cultivation. Those societies were some of the founding cultures from which totalitarian agriculture (of which modern, conventional, industrial, chemically intensive, high-input fixed-field monocrop agriculture is merely the latest iteration) emerged in a few isolated places, usually around exceptionally fertile river deltas. Each continent (except Antarctica) had such traditional farming systems, although much of the original wisdom was lost when those cultures were conquered by full-time agriculturalists, with whom they could not compete (for reasons we’ll explore below). There are quite a few other very interesting and promising approaches5, such as flood-retreat farming (explored in greater detail in Graeber & Wengrow, 2021) and Polynesian/Melanesian fixed-field horticulture, which would merit their own detailed assessment, but would hence greatly exceed the scope of this essay series.

In Central America, the Milpa system devised by the Maya and still practiced by their descendants also utilizes disturbance (fire) and natural succession, and is another textbook example of a sustainable, traditional method of slash-and-burn. Since the Maya are not hunter-gatherers and my focus is on Southeast Asian swiddeners (and for reasons of brevity, of course) I have chosen to omit a detailed discussion of the Milpa system from this essay. In many respects it is similar to indigenous methods of shifting cultivation throughout the tropics – what makes the Milpa system interesting is that it was devised by a culture that once built a civilization, and it relies less on rotation but can be practiced in the same places again and again, roughly following 20-year cycles (sometimes less, sometimes more).

Instead of rice, maize (also a grass) is planted for the first four years after the initial clearing (providing at least two crops per year). Afterwards, trees and shrubs are planted and allowed to establish themselves from seeds spread by wild animals living in the surrounding forest. Cultivars of all kinds, both annuals and perennials, and other useful plants continue to produce harvests for another eight years, until they are shaded out by the emerging forest. For the next eight years, the canopy closes, the trees continue to grow and provide habitat for wildlife, as well as harvests of fruit and forest products, until the 20-year mark is reached and the cycle can start anew (Ford, 2015).

It is highly likely that people have experimented with small-scale plant cultivation and wildtending for much, much longer, but it is well-nigh impossible to find definite archaeological evidence supporting this claim. As Daniel Quinn has argued, certain cultures have probably cultivated some of their food for a really long time, but the split between horticulture and agriculture happened when some cultures decided to grow all of their food. The difference is enormous, especially over longer periods of time. Agriculture is expansive in its nature, and was so since the beginning. There is now compelling genetic evidence that the first farmers spreading from the (once) Fertile Crescent into Europe didn’t convert and assimilate native European hunter-gatherers, but literally replaced them. We can imagine how that looked in practice. The immense surpluses produced by agriculture are inevitably followed by an increase in population6, which in turn necessitates bringing new land under cultivation – a positive feedback loop. At the same time, agriculture degrades the soil: it is exposed to sun, wind and rain, and natural succession is forcefully reset each season, so the land erodes and loses its ability to regenerate itself. Together, those two factors are responsible for the relentless agriculturalist expansion we’ve witnessed over the last few millennia.7

Horticulturalist societies do produce considerable surpluses occasionally (or, better, seasonally), but usually still manage to keep their population levels in check. How? Well, first of all, most of their tree crop surplus is not storable (and hence not harvested, consumed and converted into new humans), but left in their orchards as food for wild animals – only some of which will be hunted. That’s right, shifting cultivation directly feeds other animals as well, and thus ensures high levels of biodiversity!

Another important way this relative stability in terms of population is achieved is through using medicinal plants that act as contraceptive or abortifacient. Anna Tsing writes that many Dayak women “knew herbal potions thought to induce temporary or permanent sterility,” and that “Meratus women everywhere [she] lived and visited were interested in limiting the number of children they bore.”

“Teenage girls joined bachelors in an interest in herbs that might prevent the pregnancies through which love affairs became public problems. […] Married women with young children were the most openly eager for any kind of contraceptive advice.” (Tsing, 1993)

If the population is not kept in check preventively and intentionally through herbalist practices, violent conflict is the inevitable result. As is the case with many of the semi-sedentary South American horticulturalists, when the population slowly increases and competition over desirable tracts of land intensifies, warrior cults tend to emerge and low-level warfare (in the form of occasional ambushes and raids on neighboring groups) provides people with an incentive not to overstep their boundaries.8

Among fully sedentary horticulturalists like the Papuan highlanders, the Māori, the Sāmoans or the Hawaiʻians – just like with the sedentary Natives of the American Pacific Northwest – social stratification and violent conflict is inevitable. Moving away to avoid conflict (“voting with your feet”) is no longer an option, since land is both limited (Most Pacific Islands are rather small and densely populated) and privately or communally owned. The immensely productive (!) and ecologically sustainable (!!) horticultural systems of Pacific Islanders are tremendously fascinating, important and inspiring (especially from a contemporary tropical permacultural perspective), but also inevitably lead to dominance hierarchies and warrior cults.

The only reason why Pacific Islanders didn’t develop full-blown civilizations is the fact that they didn’t plant grains as staple foods, but instead a diverse (but perishable, and thus unstorable) array of various starchy tubers (most importantly taro) and tree crops like breadfruit. Because those crops are inherently difficult to store, measure and assess, this automatically imposes an upper limit on the degree to which specialization of labor (and thus bureaucracy and complexity) is possible – among Native Hawaiʻians, even royalty (ali’i) and priests/specialists (kahuna) were usually directly involved in food production.

State formation (and thus Civilization) can only take off if it is fueled by ample grain surplus and surrounded by vast and fertile lands (Scott, 2017).

It is sometimes objected that contemporary horticulturalists cannot serve as ethnological examples of pre-colonial (or pre-contact) societies, and especially the prevalence of crops native to the Americas among Old World horticulturalists (evident in the list of crops at the beginning of the first Part of this series) seems to support this claim.9

But there is no reason to believe that pre-Columbian-Exchange shifting cultivation was substantially different in terms of technique – the assortment of crops was just slightly smaller, with Old World crops like taro, certain yams, sago palm and banana10 dominating the mix. If anything, the introduction of New World crops made life as non-state shifting cultivators a lot easier, since more opportunities were opened up (such as among the Hmong, who could easier evade the Han state once maize was introduced, since growing hill rice confined them to altitudes below 1000 meters – and maize thrives hundreds of meters above that line).

As civilizations “progressed” and slowly expanded both their reach and influence, the new horticultural opportunities enabled by the Columbian Exchange provided the hill cultures with new means to evade and escape the claws of civilization even more efficiently.

As all this clearly shows, shifting cultivators quite obviously don’t want to become state subjects or subordinates of any kind – let alone build civilizations! – which leads us to the next question.

Are shifting cultivators anarchists? Read the next Part here!

I write stuff like the above in my free time, when I’m not tending the piece of land we’re rewilding here at Feun Foo. As a subsistence farmer by profession I don’t have a regular income, so if you have a few bucks to spare please consider supporting my work with a small donation:

If you want to support our project on a regular basis, you can become a Patron for as little as $1 per month - cheaper than a paid subscription!

The “fire farming” practiced by most Native American cultures had a different objective – maintaining grasslands, rather than forests. In environments with enough rainfall (and especially in the tropics), I think we should always try to aid in the creation of forests, because (at least in the tropics) they sequestered more carbon in a shorter time than grasslands.

One example from the literature is the Waorani (previously called Auca) in Peter Broennimann’s 1981 ethnography Auca on the Cononaco: Indians of the Ecuadorian Rain Forest – email me if you want the PDF.

One of the main reasons why rice is commonly planted into flooded paddies is for weed suppression. When swiddening, weed suppression is not an issue, since the fire basically sterilizes the first few centimeters of topsoil. The rice sprouts before the weeds and soon outcompetes most of them – but some species of “weeds” are actually encouraged because they’re edible or otherwise useful.

Schmachtenberger elaborates: “You can be a hunter and kill a buffalo while still being animistic. You can pray to the spirit of the buffalo, you can take no more buffalo than you need and use it all well, you can cry when you kill it, and then say ‘I’m eating you, we’re gonna get buried when we die and become grass that your great-grandchildren will eat, and we’re part of this great cycle of life.’ So I can let an animal have a free and sovereign life and be a predator and be part of that, and still be animistic. But I can’t yoke a buffalo. I can’t breed it into an ox, yoke it, cut its testicles off, bind its horns, and beat it all day long - and be animistic and still respect the spirit of the buffalo.” (From minute 36:00 onward in the interview.)

Some of those approaches are described by indigenous scholar Lyla June in this video.

That an increase in food availability is followed by an increase in population – and vice versa – is basic population ecology, yet this important connection is still highly controversial in public debates. People have a hard time accepting that the same rules that apply to all other animals also apply to us humans.

The same two factors are the reason why agriculturalists have always won in conflicts against hunter-gatherers: you simply can’t outbreed them, and because of their near-constant need for expansion, they will infringe on your land eventually. It’s a battle that, especially over the long term, cannot be won by the foragers.

Overly dogmatic hardliner primitivists might use this as evidence for the “one step down the road towards civilization” narrative, but violence is – whether we like it or not – the natural response to overcrowding, of humans and most other animals.

Moreover, you simply cannot expect that you won’t have any violent conflict as immediate-return hunter-gatherer. Even among the (immediate-return) Penan of Borneo, violent raids resulting from interpersonal feuds were occasionally carried out in the past, in which sometimes entire families were wiped out. Many bands on Penan were thus on bad terms and chose to avoid one another until they decided to unite against the logging industry in the 1980s (Manser, 2004).

I might add that primitive warfare and organized warfare (waged by larger agricultural societies) are, if not two different things entirely, then at the very least vastly different in order of magnitude. For starters, hunter-gatherers don’t have the time and resources to train and feed standing armies of professional combatants, so casualties are generally much lower. Foragers often rely on their neighbors for trade and marriage partners, so there is no incentive to exterminate them. Since each group already has their designated territory, there is no need to invade and ‘colonize’ other people’s land. Slavery is very uncommon, even among delayed-return hunter-gatherers, since there simply isn’t much hard work to do anyways, and whatever tasks need to be done are quite enjoyable.

Wherever the scale of slash-and-burn has increased substantially due to the introduction of chainsaws, there is truth to that objection. Shifting cultivation threatens to become just as destructive as agriculture as the cultures practicing it undergo cultural collapse and increasingly adopt the anthropocentric worldview. But the few isolated societies that are still able to practice traditional subsistence strategies are excellent examples.

Higher up in the mountains where the climate was cooler, other Old World staples like oats, barley, fast-growing millets and buckwheat, as well as cabbage and turnips, could be grown by those seeking autonomy from the state (Scott, 2009).

Another great read, but I wonder if you fall into the same trap of mischaracterising "totalitarian agriculture". Most preindustrial settled agricultural systems relied on long fallow periods to restore fertility (usually tied in to rotational mixed livestock grazing). Annual plowing and cropping is only possible in most places with industrial fertility inputs. An exception might be paddy rice systems, but the most successful of these recycled human waste on a gargantuan scale (itself supplemented by input of seafood into the human diet).

I also wonder about the symbiosis between settled and swidden agriculture. The latter presumably couldnt maintain the social complexity to forge their own iron tools, so they relied on trade with the settled agriculturalists in order to use much more efficient tool kits. In many ways this system is reminiscent of the relationship between farmers (on the flat/rich land) and pastoralists (on the hilly/dry land) in many parts of the world. Perhaps if there were tropical adapted grazing livestock that could move around the rainforest hills they would replace the swidden farmers to some extent.

Looking forward to part III